There is a well documented disparity between health outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and those for the non-Aboriginal Australian population.1 The reasons for this disparity are complex and multifactorial. Aboriginal children in remote areas are more likely to suffer from infectious illnesses as a direct result of factors such as overcrowded housing.2 There is also concern about the increasing risk of diabetes, obesity, and the social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal children living in both urban and rural environments.3–5

Despite this high burden of disease, Aboriginal children and their families are less likely to interact with health care services.2,6,7 Contributing factors to this lack of engagement include racism, lack of cultural security, restricted access to and choice of services, inadequate community consultation, and prior negative health care experiences.6,8–10 In addition, many services are not perceived as welcoming to Aboriginal families.1,11 Aboriginal children are more likely to present later to hospital than is optimal, and to be admitted after presenting to an emergency department.12

In Western Australia, the Koorliny Moort out-of-hospital care coordination program was designed to bridge the gap in providing services to Aboriginal children who need hospitalisation or out-of-hospital services. Koorliny Moort means “Walking with families” in the language of the Noognar people of the Whadjuk Nation. The Noongar people are the traditional owners of the land on which Princess Margaret Hospital for Children is located.

The primary objective of our study was to assess the effect of the Koorliny Moort program on emergency department presentations. Secondary objectives were to assess its effect on hospital admissions, length of stay, and out-of-hospital follow-up appointments. We also assessed whether these effects were modified by age at referral, geographic region or referral source.

Methods

Setting

The Koorliny Moort program has been part of service provision at Princess Margaret Hospital for Children since 1 August 2012. Princess Margaret Hospital provides tertiary inpatient and outpatient services to all children in WA. The Koorliny Moort program was funded to include the three WA regions that include 70% of all Aboriginal children in WA (Kimberley, Pilbara, Perth metropolitan).

Inclusion criteria

All Aboriginal children aged 0–16 years who resided in the Kimberley, Pilbara or Perth metropolitan regions were eligible for the program. Referrals were accepted from Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHS), general practitioners, allied health staff, Medicare Locals, community workers, and specialist doctors. Self-referrals from families were also included.

Referrers were encouraged to refer children who had failed to attend appointments or who had complex problems or social or behavioural problems, or when the referrer experienced difficulties engaging with the family. We also accepted referrals from families who wished their children to be reviewed closer to home and country.

Interventions

The Koorliny Moort team included an Aboriginal senior program manager, two nurses, an administrative assistant, a senior Aboriginal senior social worker, two Aboriginal liaison officers, two part-time developmental paediatricians, and a senior paediatric trainee doctor.

The program provided three key interventions: partnership with community-based primary care providers (especially ACCHS), nurse-led care coordination, and outreach care closer to home. Partnerships with primary care providers included those with ACCHS, general practitioners, practice nurses, community health nurses, Medicare Locals, and social services. We provided support for following up clients, as well as training and capacity building for improving skills and knowledge in developmental and ambulatory care for Aboriginal children. Nurse-led care coordination involved assistance with combining and coordinating appointments to minimise travel and disruption, providing choices for appointments closer to family homes, assisting in locating medical records and results, planning hospital discharge, providing health advice and social, cultural and family support, and telehealth services. Outreach care encompassed social work, and nursing and paediatrician follow-up care as close to the family home as possible, including outreach clinics, assistance with social problems, vaccination, and developmental paediatric management.

Data collection

The administrative assistant collected data about the date of referral, reason for and source of the referral, and the age, sex and postcode of residence of the child. An independent analyst extracted de-identified data on hospital admissions, length of stay, emergency department presentations and outpatient appointments (attended and non-attended) from WA Department of Health databases.

Analysis

All children who were referred between 1 August 2010 and 31 July 2014 and for whom at least 2 months of pre- or post-program data were available were included in the analysis. Each child acted as their own control. The pre-program period extended from 1 August 2010 to the time of referral. The post-program period was from the time of referral to 31 July 2014. If a child was born after 1 August 2010, the date of birth was used as the base point. Occasions of service and person-time (in days) were compared for each child before (pre-program) and after their referral (post-program).

The proportion of children who received at least one occasion of service (emergency department presentations, hospital admissions) was calculated, with the total number of children who had at least one occasion of service as the numerator and the total number of children in the program as the denominator. For the analysis of non-attended appointments, the denominator was the number of children who had had at least one scheduled appointment. Logistic generalised estimating equations were used for analysis, and odds ratios calculated. This approach is often used to analyse variables that can be correlated over time, such as the frequencies of health care events in pre- v post-intervention designs.

The incidence of occasions of service was calculated using the number of occasions of service as the numerator and the total number of person-days as the denominator. Analyses also used generalised estimating equations modelling, and incidence rate ratios (IRRs) were calculated. Negative binomial models with an exchangeable correlation structure were used because count data were overdispersed.

We also assessed whether the effect of the Koorliny Moort program was modified by age at referral (children under 5 years of age v those at least 5 years old), geographic region (Perth metropolitan v non-metropolitan WA) or referral source (primary care staff v other referral source). Statistical analyses were performed with Stata 13.1 (StataCorp).

Sample size determination

Sample size estimations were based on the primary outcome measure (proportion of children with at least one emergency department presentation). We calculated that 820 children were needed to detect an improvement of at least 20% in emergency department presentations (α = 0.05, 80% power; assuming a baseline prevalence of 50%).

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the WA Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee and the Child and Adolescent Health Service Ethics Committees.

Results

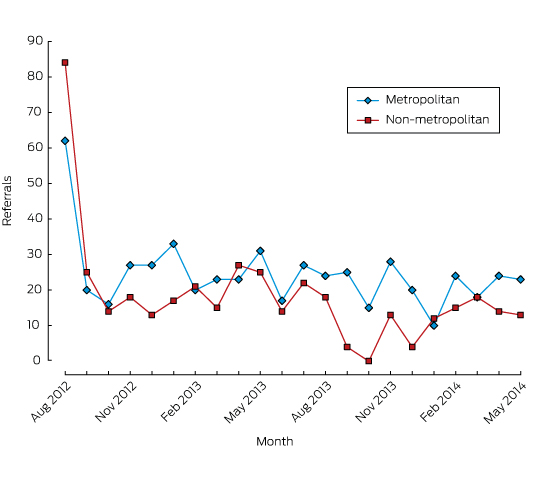

Between 1 August 2012 and 31 May 2014, 942 children were referred to the program (Box 1). The mean time spent by children in the program was 383.7 days (SD, 198.1 days).

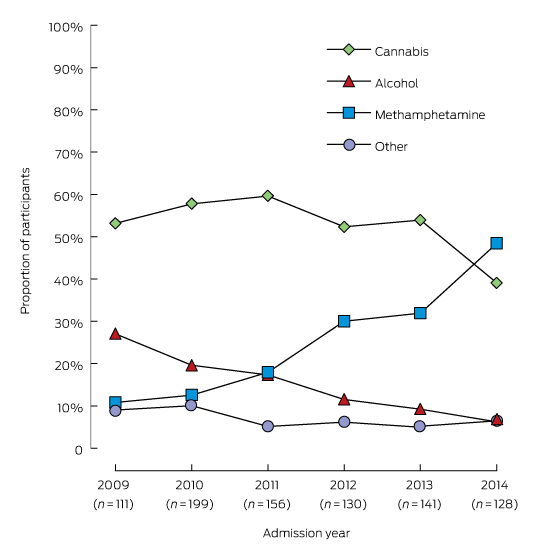

More than half (57%) of the referrals were from the metropolitan region, and 501 children (53%) were under 5 years of age at the time of referral. One hundred and twenty-two of our children (13%) were adolescents aged 12–19 years; 309 (33%) resided in areas with the greatest socio-economic disadvantage (Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas [SEIFA] quintiles 1 and 2)13 (Box 2). Primary care providers had referred 429 of the children (46%), and ACCHS 237 (25%). More than half the children (55%) had multiple health problems. Of these, 17.4% were classified as having developmental delay and 11.7% had behaviour or mental health problems. In the metropolitan region, referrals for children with problems related to social and emotional wellbeing accounted for 45% of referrals (Box 3).

The proportion of children with at least one emergency department presentation decreased significantly from 44.8% during the pre-program period to 21.1% during the post-program period (odds ratio [OR], 0.33; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.23–0.40; P < 0.001) (Box 4). The incidence of emergency department presentations also decreased significantly (IRR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.43–0.53; P < 0.001) (Box 5).

The proportion of children with at least one hospitalisation significantly decreased from 43.7% during the pre-program period to 28.3% in the post-program period (OR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.43–0.61; P < 0.001) (Box 4). The incidence of hospitalisation also decreased significantly (IRR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.62–0.79; P < 0.001), as did length of stay (IRR, 0.23; 95% CI, 0.21–0.25; P < 0.001) (Box 5).

The number of children with at least one scheduled appointment increased by 17 percentage points from 587 children (62%) pre-program to 742 (79%) post-program (Box 4, Appendix 1). Characteristics of children with and without scheduled appointments were similar (Appendix 1). The proportion of children who failed to attend at least one outpatient appointment decreased significantly from 67% in the pre-program period to 58% post-program (OR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.56–0.87; P = 0.001) (Box 4). The incidence of non-attended appointments also significantly decreased (IRR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.74–0.94; P = 0.003) (Box 5).

In the stratified analyses, the effect of the program was not modified by region or referral source (Box 5, Appendix 2). In contrast, the effect of the program on outpatient non-attendance was modified by age group (Box 5). The program significantly reduced outpatient non-attendance by 31% in children younger than 5 years old (IRR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.58–0.82; P < 0.001), but not in children aged 5 years or more (IRR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.83–1.18; P = 0.915; for interaction between age and program: P < 0.001). The effect of the Koorliny Moort program on emergency department presentations and hospitalisation was not significantly affected by age group (Box 5).

Discussion

Our program reduced emergency department presentations and hospitalisations and improved attendance at outpatient appointments by referred Aboriginal children. These effects were observed in children from both metropolitan and regional areas, and these effects were sustained over the 2 years of the program. These findings suggest that it is possible to positively influence the health-seeking behaviour of families of Aboriginal children by engaging Aboriginal people in their health care, providing effective communication between health service providers, and delivering a coordinated program of care led by Aboriginal service providers. These conclusions are especially important given that Aboriginal children are among the most difficult to reach and the most disadvantaged children in WA, as reflected in the extremely high non-attendance rate at appointments before the introduction of our program.

The proportion of children who received scheduled appointments increased by 17 percentage points, indicating an overall increase in access to care. Improvements were observed among children from both metropolitan and non-metropolitan regions, regardless of referral source, suggesting that our service was both effective and able to meet the needs of rural and primary care providers. Our program showed greater effects on outpatient attendance in children under 5 years of age. Thirteen percent of our children were adolescents aged 12–19 years. It is known that adolescents are difficult to engage and make poor use of health care services,14,15 but the sample size was not sufficient to separately assess the effects of the program in this important age group.

The impact of our program is consistent with previous investigations that have found the use of health care services can be improved by ambulatory care, central coordination and inter-agency communication.12,16–18 However, few studies have assessed the effects of out-of-hospital care on health service use by disadvantaged and Aboriginal populations. Out-of-hospital Aboriginal midwifery group practices report improved utilisation and satisfaction rates of 40–60%.19–21 Innovative ACCHS services have also been reported to improve satisfaction and quality of care.19,20 However, there appear to be no studies that have examined the impacts of out-of-hospital services on disadvantaged Aboriginal children. A recent study reported that more than 40% of presentations by Aboriginal children to emergency departments could be categorised as preventable.11,22 However, our study is the first to test and evaluate an approach to improving out-of-hospital services for Aboriginal children.

Our study has some limitations. The program provided three key interventions that improved the choice of services offered to families, but we were not able to assess the effects of the individual components of the intervention, as they were interconnected. The study participants were selected by a restricted number of pathways, and the final sample may not be fully representative of the wider community. A cluster randomised controlled trial would have been a better design, but it was not possible to implement such an approach in our complex service environment. We also considered whether the reduction in hospitalisations and emergency department presentations could be explained by the natural history of childhood illnesses, which tend to improve over time or as the child grows up. However, all of the children had complex chronic medical problems or medical conditions that required intensive medical and developmental care for a number of years, and their post-program use of hospital services remained high.

Our study has a number of implications for policy and program development. Many investigations, particularly of Aboriginal health, have described problems without attempting to test potential solutions. Our findings suggest it is possible to improve health-seeking behaviour and health outcomes for Aboriginal children by engaging Aboriginal families with health services, improving communication between health service providers, and coordinating Aboriginal service provider-led care. However, more information about the individual components of the program is needed, as well as about the perspectives and priorities of Aboriginal families and service providers. We are undertaking a qualitative project to examine these aspects, and will use the results to improve our program. We are also aware that our focus was on the most complex children with established medical conditions. Funding and service delivery, however, should be directed towards prevention and early detection rather than to tertiary services. We are developing a program to improve the primary care of disadvantaged Aboriginal children, and will report on its effects in a future article.

Box 2 –

Demographic data for the children referred to the Koorliny Moort program, 1 August 2012 – 31 May 2014, by region of residence

|

|

Metropolitan |

Non-metropolitan |

Total |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Number of children (% of total sample) |

536 (57.2%) |

406 (43.1%) |

942 |

||||||||||||

|

Number of children under 5 years of age (%) |

290 (54.1%) |

211 (52.0%) |

501 (53.2%) |

||||||||||||

|

Mean age of children (SD), months |

65.9 (55.9) |

69.5 (58.5) |

67.5 (57.0) |

||||||||||||

|

Number of boys (%) |

309 (57.6%) |

228 (56.2%) |

537 (57.0%) |

||||||||||||

|

Number of children residing in most disadvantaged areas* (%) |

52 (9.7%) |

257 (63.3%) |

309 (32.8%) |

||||||||||||

|

Number of children referred by Aboriginal medical service staff (%) |

159 (29.7%) |

78 (19.2%) |

237 (25.2%) |

||||||||||||

|

Number of children referred by primary service providers (%) |

328 (61.2%) |

101 (24.9%) |

429 (46.1%) |

||||||||||||

|

Mean number of specialists (SD) involved before program began |

2.2 (2.3) |

2.0 (2.1) |

2.1 (2.2) |

||||||||||||

|

Mean number of child-days (SD) in the program |

427 (201) |

476 (206) |

448 (204) |

||||||||||||

|

Median number of child-days (IQR) in the program |

442 (260–597) |

492 (345–680) |

465 (272–630) |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

IQR = interquartile range; SD = standard deviation. All percentages are column percentages, except in the first row (number of children). * Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) quintiles 1 and 2. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 –

Reasons for referral of children to Koorliny Moort, 1 August 2012 – 31 May 2014*

|

|

Metropolitan |

Non-metropolitan |

Total |

||||||||||||

|

Number |

% |

Number |

% |

Number |

% |

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Number of children |

536 |

|

406 |

|

942 |

|

|||||||||

|

Social and emotional wellbeing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Developmental delay |

141 |

26.3% |

23 |

5.7% |

164 |

17.4% |

|||||||||

|

Behaviour |

83 |

15.5% |

8 |

2.0% |

91 |

9.7% |

|||||||||

|

Mental health |

18 |

3.4% |

1 |

0.2% |

19 |

2.0% |

|||||||||

|

Surgical |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Orthopaedics |

36 |

6.7% |

106 |

26.1% |

142 |

15.1% |

|||||||||

|

Ophthalmology |

30 |

5.6% |

39 |

9.6% |

69 |

7.3% |

|||||||||

|

Ear, nose and throat |

40 |

7.5% |

51 |

12.6% |

91 |

9.7% |

|||||||||

|

Plastics |

13 |

2.4% |

25 |

6.2% |

38 |

4.0% |

|||||||||

|

Dental |

4 |

0.7% |

10 |

2.5% |

14 |

1.5% |

|||||||||

|

Burns |

3 |

0.6% |

6 |

1.5% |

9 |

1.0% |

|||||||||

|

Other surgical |

16 |

3.0% |

45 |

11.1% |

61 |

6.5% |

|||||||||

|

Medical |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Neurology |

62 |

11.6% |

63 |

15.5% |

125 |

13.3% |

|||||||||

|

Respiratory |

63 |

11.8% |

47 |

11.6% |

110 |

11.7% |

|||||||||

|

Prematurity |

47 |

8.8% |

26 |

6.4% |

73 |

7.7% |

|||||||||

|

Nutrition |

41 |

7.6% |

14 |

3.4% |

55 |

5.8% |

|||||||||

|

Infectious disease |

36 |

6.7% |

10 |

2.5% |

46 |

4.9% |

|||||||||

|

Cardiac |

30 |

5.6% |

20 |

4.9% |

50 |

5.3% |

|||||||||

|

Renal |

29 |

5.4% |

15 |

3.7% |

44 |

4.7% |

|||||||||

|

Endocrine |

29 |

5.4% |

17 |

4.2% |

46 |

4.9% |

|||||||||

|

Haematology/oncology |

8 |

1.5% |

5 |

1.2% |

13 |

1.4% |

|||||||||

|

Gastroenterology |

41 |

7.6% |

12 |

3.0% |

53 |

5.6% |

|||||||||

|

Other medical |

28 |

5.2% |

17 |

4.2% |

45 |

4.8% |

|||||||||

|

More than one problem |

247 |

46.1% |

272 |

67.0% |

519 |

55.1% |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Children could have more than one referral problem. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 –

Proportion of children who had at least one occasion of service, pre- and post-Koorliny Moort program, 1 August 2012 – 31 May 2014

|

|

Pre-Koorliny Moort Program |

Post-Koorliny Moort Program |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

P |

|||||||||||

|

Total children |

Number (%) |

Total children |

Number (%) |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Emergency department presentations |

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

Total |

942 |

422 (44.8%) |

942 |

199 (21.1%) |

0.33 (0.27–0.40) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||

|

Metropolitan |

536 |

285 (53.2%) |

536 |

149 (27.8%) |

0.34 (0.27–0.43) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||

|

Non-metropolitan |

406 |

137 (33.7%) |

406 |

50 (12.3%) |

0.28 (0.20–0.39) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||

|

Hospital admissions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Total |

942 |

412 (43.7%) |

942 |

267 (28.3%) |

0.51 (0.43–0.61) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||

|

Metropolitan |

536 |

219 (40.9%) |

536 |

121 (22.6%) |

0.42 (0.33–0.54) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||

|

Non-metropolitan |

406 |

193 (47.5%) |

406 |

146 (36.0%) |

0.62 (0.75–1.10) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||

|

Non-attended appointments* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Total |

587 |

394 (67.1%) |

742 |

432 (58.2%) |

0.69 (0.56–0.87) |

0.001 |

|||||||||

|

Metropolitan |

320 |

232 (72.5%) |

440 |

282 (64.1%) |

0.68 (0.51–0.92) |

0.011 |

|||||||||

|

Non-metropolitan |

267 |

162 (60.7%) |

302 |

150 (49.7%) |

0.66 (0.48–0.90) |

0.009 |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* For the analysis of non-attended appointments, the denominator was the number of children with at least one scheduled appointment. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 5 –

Incidence of occasions of service, pre- and post-Koorliny Moort program, 1 August 2012 – 31 May 2014*

|

|

Pre-Koorliny Moort program |

Post-Koorliny Moort program |

Unadjusted IRR |

||||||||||||

|

Event incidence rate (per 1000 person-days) |

Mean number of events (SD) |

Event incidence rate (per 1000 person-days) |

Mean number of events (SD) |

IRR (95% CI) |

P |

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Emergency department presentations |

|||||||||||||||

|

Total |

1.96 |

1.14 (2.19) |

0.98 |

0.44 (1.26) |

0.47 (0.43–0.53) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||

|

Hospital admissions |

|||||||||||||||

|

Total |

857 |

0.91 (2.59) |

1.16 |

0.52 (1.52) |

0.70 (0.62–0.79) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||

|

Length of hospital stay |

|||||||||||||||

|

Total |

8.81 |

5.14 (15.10) |

3.44 |

1.54 (6.42) |

0.23 (0.21–0.25) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||

|

Non-attended appointments |

|||||||||||||||

|

Total |

4.06 |

2.50 (3.72) |

3.53 |

1.63 (2.31) |

0.83 (0.74–0.94) |

0.003 |

|||||||||

|

Children, < 5 years of age |

4.57 |

2.29 (3.45) |

3.53 |

1.61 (2.26) |

0.69 (0.58–0.82) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||

|

Children, ≥ 5 years of age |

3.72 |

2.71 (3.96) |

3.54 |

1.65 (2.37) |

0.99 (0.83–1.18) |

0.915 |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

IRR = incidence rate ratio (pre- v post-Koorliny Moort program). * This table summarises the unstratified analysis (all 942 children); the stratified results by age for non-attended appointments are also included because they provide the only instance of a significant difference. For full summary of stratified results, see Appendix 2. |

|||||||||||||||

more_vert

more_vert