Children’s eye injuries prompt calls for increased adoption of eye protection for children at risk

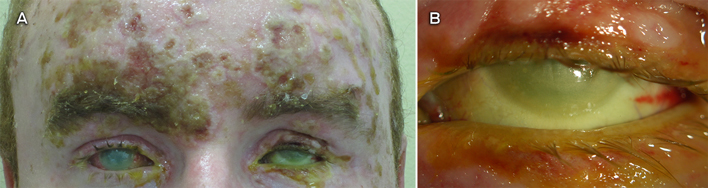

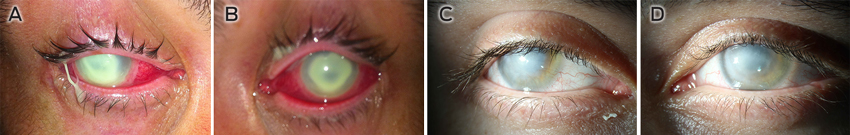

Ocular injuries are common in childhood, and their aetiology and epidemiology are well documented.1,2 Internationally, 20%–59% of all ocular trauma occurs in children (male to female ratio, 3.6 : 1), with 12%–14% of cases resulting in severe monocular visual impairment or blindness.2,3 In 2009, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare identified that people aged < 19 years represented 15.6% of eye-related emergency department presentations between 1999 and 2006.4 Most eye injuries in children occur at home (76%), with the remainder occurring during sport and other recreational activity.2,3,5 In a recent New South Wales study, open globe injuries accounted for 40% of ocular trauma in children; of these, 48% occurred at home and involved common household objects.6 In 2000, 2.4 million eye injuries in the United States were related to sporting activity; 43% in children aged < 15 years and 8% in children aged < 5 years.7 Retrospective studies in Australia have shown that eye injuries from sporting activities accounted for 10% of severe ocular trauma in children, with permanent visual damage occurring in 27% of these cases.1 However, there is a lack of detailed information regarding the nature and incidence of children’s sporting eye injuries.

Due to their developing physical coordination, limited ability to detect risks inherent in the environment and vulnerable facial morphology, children are at higher risk of ocular trauma compared with adults of working age.5 Moreover, given that a child’s visual development continues from birth until 7–8 years of age, visual outcomes following trauma in children are worse than adults, affecting their subsequent career and social opportunities as adults.2 By adopting simple protective measures, such as using eye protectors when necessary, 90% of ocular injury is preventable.8

Outcomes of intervention in eye protection

A decline in paediatric ocular injuries in some sports, including lacrosse, field hockey, ice hockey and hurling, has been attributed to the adoption of mandatory protective eyewear in Canada, the US and Ireland. In the US, children’s eye injuries in lacrosse dropped by 84% following the introduction of mandatory eye protection in 2010.9 Key to effective implementation of eye-protection programs has been the development of product standards and policy statements by supporting organisations such as the American Academy of Ophthalmologyand American Academy of Pediatrics.5,7,9 In Australia, Squash Australia has set down strict guidelines for use of eye protectors in children (regulation 42, http://www.squash.org.au/sqaus/regulations_policies/regulations.htm [accessed Mar 2014]), but no studies have been conducted to review the effectiveness of this intervention.

Hurdles to effective use of protective eyewear in children

Significant research has been undertaken on the aetiology and management of eye injuries in children worldwide.3,5,7 However, there is less emphasis on research, public policy development and promotion of protective eyewear to reduce the incidence of eye trauma and vision loss. Occupational adult eye injuries have been found to decrease significantly with the use of eye protection.10 Little information is available in the scientific and grey (public domain) literature regarding protective eyewear in children; information for the general public is similarly limited.

Studies have shown that despite an awareness among adults, caregivers and children (particularly 15–18-year-olds) of the need for children’s eye protection, the rate of use remains low at about 19%.11 Parents and peers are major influences on attitudes to the use of eye protectors, with media not playing an important role. Deterrents to using appropriate eye protection include discomfort, poor visibility, unsuitable material, cosmetic appeal, availability, cost, storage and accessibility, no formal education on eye protection, and the perception that eye protectors are unnecessary.11

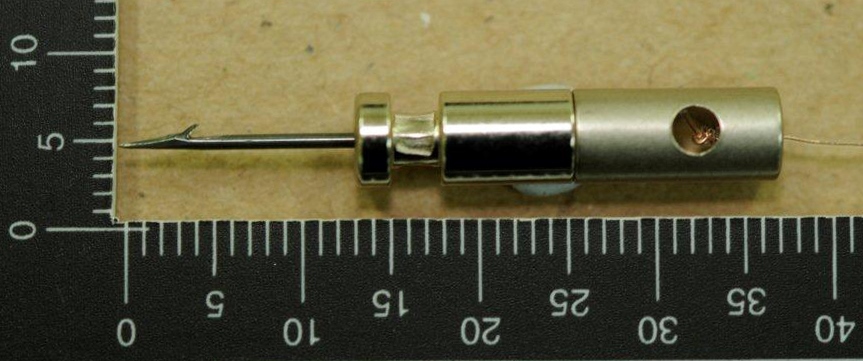

Regular (dress optical) spectacles are not an adequate substitute for eye protectors and can pose an additional danger due to the nature of the lens materials and the frame design.12 Because of its superior impact resistance, polycarbonate is the material of choice for prescription eye-protector lenses, but higher cost and the perception of its reduced scratch-resistance inhibit its uptake.13

Strategies to reduce ocular trauma in children

To address the large gaps in research and public policy regarding children’s eye protection, a multilevel approach is required to influence change in risk-reduction behaviour. Development, promotion and use of eye protection for children can be achieved through education and standards and policies.

Any approach to reduce the incidence of eye injuries should attempt to remove or limit hazards. Keeping potentially hazardous chemicals such as dishwashing liquid, toilet cleaners, paint, superglue and sprays out of young children’s reach, and purchasing toys that are appropriate for age and do not have sharp or projecting edges, can help protect children’s eyes.5 While it is impractical to suggest that a child wear eye protectors all the time, as most eye injuries in children occur at home, children’s activity should be supervised by a responsible adult, particularly when the child is exposed to potentially hazardous household items such as scissors, knives and other sharp objects.

Children, parents and caregivers, teachers, coaches and sports venue operators need to be reminded of the risks involved with particular sporting activities and the type of eye protectors that are available. Children who are at higher risk of eye injury — such as those who have experienced ocular surgery, trauma or disease, and functionally one-eyed individuals — should be encouraged to wear eye protection for all medium to high-risk activities and avoid sports or activities where no adequate eye protection is available.7 Health campaigns are essential to promote eye protection, using mass media to highlight the problems of eye damage in terms of blindness and its long-term impact. The support of professional organisations, local and national eminent people, eye-protection manufacturers and policymakers is important. Doctors and health professionals also play a key role in increasing public awareness and developing positive attitudes towards eye protection.

Standards in Australia currently focus on occupational more than domestic and sports eye protection. Internationally, there is a lack of standards and policies specifically for children’s eye protection. Of 43 spectacle and eye-protection standards for occupational and recreational requirements in the UK, US, Canada, Europe and Australia, only 21 allow for the specific needs of children. Most of the limited number of policies developed to prevent children’s eye injuries have focused on sports eye-protection requirements. It is imperative that policies and standards reinforce the needs of children who are functionally one-eyed and those at higher risk of ocular trauma to ensure that their vision is adequately protected.

Development of more advanced materials like polyurethane for occupational and sports eye protection has allowed for improved comfort and fit for adults. Children’s eye protection is yet to benefit from many of these advances. The optimal eye protector allows clear, distortion-free vision with a lens that does not fog, in a frame that is stylish and comfortable with adequate coverage and impact resistance. This highlights the need for spectacle designers to develop eye-protection solutions for children that meet standards requirements as well as addressing other issues to maximise compliance and use.

The way forward

To enable adequate measurement of the impact of interventions, the lack of detailed eye-injury data in Australia will need to be addressed. Long-term follow-up studies are required to improve our understanding of the nature and incidence of children’s eye injuries. Critical to the sustainability of any injury-prevention program is the ability to measure behaviour change following an intervention, to improve and develop more effective programs. Health education regarding eye protection should not stop with awareness campaigns but must be an ongoing process — awareness is highest soon after a campaign, after which it diminishes.

An improved understanding of the reasons for non-compliance with existing eye-protection recommendations will enable increased success of eye-protection programs. Importantly, we need an understanding of the current knowledge, influences and societal practices regarding ocular injuries, as well as the perception of risk, adequacy and subsequent use of eye protectors before and after an intervention.

Gaps in the current standards for children’s eye protection provide an important opportunity for a change in policies, recommendations and legislation, as well as for gaining support from relevant individuals and bodies. We have identified the need for specific standards to protect functionally one-eyed children and those at higher risk of eye injury; to determine when dress optical spectacles should be replaced with prescription eye protectors; and to identify which sports and recreational activities pose a medium to high risk of eye injury and require that participants use eye protection.

more_vert

more_vert