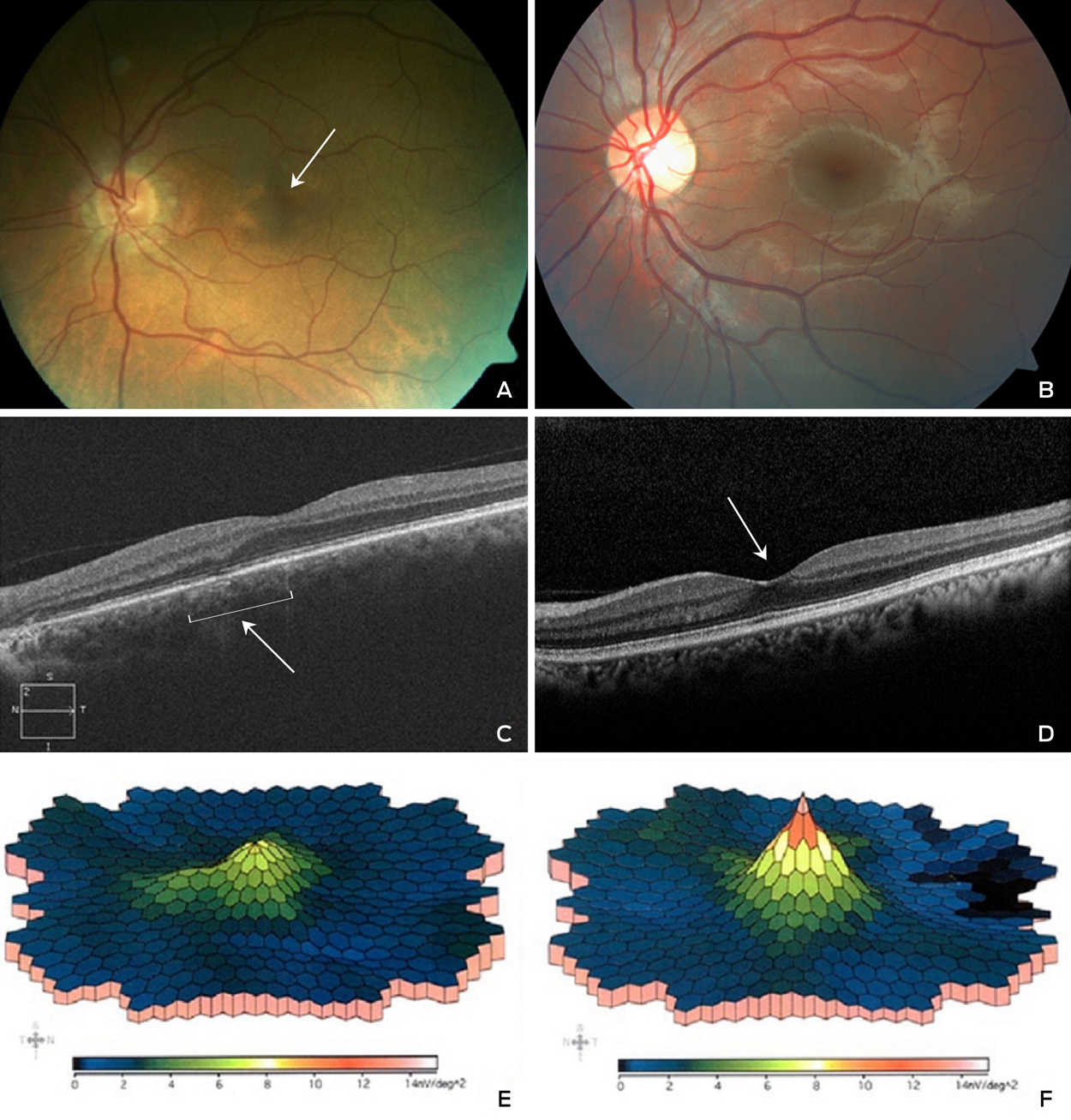

A 57-year-old man was treated for schizophrenia with clozapine 900 mg daily over 22 years. His history included epilepsy, hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia, which was treated with clonazepam, clonidine and atorvastatin. Examination showed acuity 6/5 bilaterally, corneal and macular pigmentation (Figure, A, arrow, compared with B, which is normal macula), with subfoveal atrophy and disruption of the photoreceptor-retinal pigment epithelium junction on optical coherence tomography scan ([OCT]; Figure, C compared with D, which is a normal OCT, arrows), and left eye macular dysfunction on multifocal electroretinography ([ERG]; Figure, E compared with F, which is a normal ERG). These changes were similar to previously described clozapine-associated retinopathy.1 Clonazepam is associated with depigmentary retinopathy and normal ERG responses.2 Clonidine and atorvastatin have no documented retinopathy. The patient’s hyperpigmentation may be due to clozapine absorption via the choroid, binding to retinal pigment epithelium and interrupting photoreceptor phagocytosis.3 High dose clozapine warrants ophthalmic follow-up.

Preference: Ophthalmology

754

Ocular complications of rheumatic diseases

Most of the inflammatory rheumatic diseases are systemic conditions with clinical and pathological manifestations outside of the joints. Many of the extra-articular manifestations of inflammatory rheumatic disease respond to the same treatments that target the joint disease itself, but some require specialised interventions. Ocular involvement is a common manifestation of inflammatory rheumatic disease and ranges from chronic troublesome symptoms, such as dry eye complicating Sjögren syndrome, to organ- and sight-threatening vasculitis. Isolated ocular abnormality has been reported to account for up to 4% of referrals to rheumatology clinics.1 Diagnosing and characterising serious ocular abnormalities are complicated by the need for specialised equipment and training — notably slit lamp and retinal examination — to fully assess eye disease. Consequently, it is incumbent on physicians involved in the care of patients with rheumatic disease to be aware of the potential ocular complications of their patients’ condition and the indications for rapid escalation of treatment to specialist level to preserve sight.

Here, we summarise these important conditions, in order of urgency of treatment, for non-ophthalmologists who are involved in the management of patients with rheumatic diseases (Appendix 1). We identified articles for inclusion in this review by keyword searches in MEDLINE, with an emphasis on up-to-date review articles, and through expert opinion.

Ocular complications of rheumatic diseases

Ischaemic optic neuropathy

Ischaemic optic neuropathy refers to damage to the optic nerve caused by a lack of blood supply. It is one of the major causes of blindness in older people in the Western world. The systemic disease most often associated with ischaemic optic neuropathy is giant cell arteritis (GCA), in which arterial vasculitis most commonly affects the blood supply to the optic nerve head. This entity is termed arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy (AAION). About 22% of patients with GCA will experience visual symptoms, with 12% developing irreversible loss of vision.2

GCA, which is by far the most common cause of AAION, rarely affects patients under the age of 50 years and has a mean age at diagnosis of 72 years.3 Women with GCA develop AAION more often than do men (71% v 29%).4 Patients often present with anorexia and the systemic symptoms associated with GCA, such as a persistent temporal headache, scalp tenderness and jaw or tongue claudication. Definitive diagnosis of GCA is made by temporal artery biopsy. The symptoms associated with a positive biopsy result include jaw claudication, neck pain and anorexia.5 Importantly, up to 21% of patients who develop permanent visual loss due to confirmed GCA have no systemic symptoms.5 The visual manifestations of ischaemic optic neuropathy are characterised by painless, sudden loss of vision. Amaurosis fugax is seen in up to 30% of patients with GCA and is a sign of impending loss of vision.4 Inflammatory marker levels are elevated in most patients with GCA, but there is a small proportion of patients with biopsy-proven GCA whose levels are within the normal reference interval.6

Initiation of steroid therapy should not be delayed while awaiting a definitive diagnosis. Treatment of patients with suspected GCA is oral prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day; maximum dose, 60 mg daily) or intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone therapy. A same day referral to an ophthalmologist should be made to arrange biopsy of the superficial temporal artery. The development of amaurosis fugax or any symptoms of visual loss is an indication for pulse IV methylprednisolone therapy.7 Once GCA is confirmed by biopsy, long term oral prednisolone and regular monitoring for systemic side effects of steroids are indicated.

Retinal vasculitis

Retinal vasculitis refers to inflammation of the retinal blood vessels. The development of retinal vasculitis is most commonly reported in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus or Behçet disease. Patients who develop retinal vasculitis often progress from mild retinopathy, involving cotton wool spots, perivascular hard exudates, retinal haemorrhages and vascular tortuosity (Box 1), to complete occlusion of retinal arterioles and consequent retinal infarction. Most patients with retinal vasculitis develop proliferative retinopathy, often progressing to vitreous haemorrhage and retinal detachment.8 Evidence of mild retinopathy is seen in 10% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus8 and up to 74% of patients with the ocular form of Behçet disease.9 Permanent loss of vision is common in those patients who progress to advanced retinal vasculitis.

Retinal vasculitis typically presents with a painless decline in vision. Patients may develop a blind spot from ischaemia-induced scotomas or floaters from vitritis, and those with macular involvement may develop metamorphopsia. It is also possible for retinal vasculitis to be asymptomatic.

Same day referral to an ophthalmologist is recommended for all patients with a painless decline in vision. The diagnosis is often confirmed clinically on detailed retinal examination or with the aid of fluorescein angiography. Aggressive treatment with oral prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day; maximum dose, 60 mg daily) is recommended, often supplemented or replaced with other steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agents. Complications such as proliferative retinopathy are later treated with laser therapy.8

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis

Peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK) refers to inflammation and ulceration of the cornea. It is a rare complication of systemic diseases that is characterised by thinning of the stromal layer of the cornea close to the limbus. It is caused by inflammation of the cornea’s stromal layer and is often unilateral and crescent-shaped in appearance. There is an associated epithelial defect overlying the area of inflammation and progressive corneal thinning, which can lead to corneal perforation.10

The development of PUK is most often associated with rheumatoid arthritis but is also reported in cases of polyarteritis nodosa and granulomatosis with polyangiitis. The introduction of biological therapy for rheumatoid arthritis has seen a reduction in the incidence of corneal complications of this disease.11 PUK is reported to have a prevalence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis of 1.4–2.5%.11,12 It is seen most often in patients with longstanding rheumatoid arthritis who are both rheumatoid factor and anticyclic citrullinated peptide antibody positive. The presence of acute anterior uveitis (AAU) and dry eyes is common in patients with PUK.11

Patients with PUK often present with symptoms of ocular redness and pain, tearing, photophobia and decreased visual acuity. As the disease progresses, crescent-shaped corneal ulcers develop, with an associated corneal epithelial defect (Box 2). Inflammation of the surrounding conjunctiva and sclera are frequently apparent.10 Corneal ulceration often abates after treatment, but corneal thinning, scarring and neovascularisation are irreversible.10

The treatment of PUK is determined by the severity of findings within the cornea and the likelihood of imminent perforation. Aggressive treatment of the underlying systemic disease is important to control the progression of corneal disease, and should include a combination of high-dose systemic prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day; maximum dose, 60 mg daily) and an immunomodulatory agent appropriate to the underlying systemic disease, such as methotrexate. Pulse methylprednisolone therapy may be administered in cases of imminent perforation. Surgical management may be required to maintain globe integrity.10

Scleritis

The term scleritis refers to chronic inflammation of the sclera, the dense external covering of the eye. About 25–50% of patients presenting with scleritis have an associated systemic disease,13 most often rheumatoid arthritis (10–18.6%), although scleritis is also seen in patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis (3.8–8.1%), relapsing polychondritis (1.6–6.4%) and inflammatory bowel disease (2.1–4.1%).14 Scleritis is an important clinical entity to detect, not only because it may lead to loss of vision due to structural changes to the globe but also because it is associated with an increased mortality rate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.14 Scleritis may involve the anterior sclera, posterior sclera or both, and may be diffuse, nodular or necrotising. Non-necrotising scleritis rarely results in loss of vision, unless it is complicated by uveitis or keratitis. Necrotising scleritis results in rapid thinning of the sclera and exposure of the underlying uvea and is associated with poorly controlled systemic disease. This occurs due to severe vasculitis and closure of the episcleral vascular bed, leading to a visible area of scleral non-perfusion, infarction and necrosis (Box 3).14

Patients with scleritis present with severe pain involving the eye and orbit that radiates to the ear, scalp, face and jaw. The pain is often described as a dull, boring pain that wakes the patient from sleep and is exacerbated by eye movement. Episodes of scleritis can last several months, with the pain increasing in severity over several weeks. Patients with anterior scleritis often notice redness and tenderness of the globe. Patients with necrotising scleritis can experience extreme scleral tenderness. Inflammation often spreads to the surrounding structures, leading to keratitis, anterior uveitis and elevated intraocular pressures, all of which threaten vision.15

Patients with necrotising scleritis require treatment with systemic steroids, either orally or intravenously. A typical starting dose of prednisolone is 1 mg/kg/day (maximum dose, 60 mg daily), which is weaned over the following months based on disease progression. IV methylprednisolone is usually reserved for patients with impending scleral or corneal perforation. Patients who relapse at prednisolone doses of greater than 7.5 mg daily should be considered for adjunctive immunosuppressive therapy, such as methotrexate. Steroid therapy is combined with oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents. Surgical intervention is rarely required in cases of scleral or corneal perforation, which can often be managed with contact lenses and tissue adhesive.15

Uveitis

Uveitis is inflammation of the uvea, the layer of the eye between the outer sclera and the inner retina. It is the most frequently encountered ocular manifestation of rheumatic disease and is responsible for up to 10% of cases of blindness in Western countries.16 Uveitis is classified as anterior, intermediate, posterior or panuveitis, based on the anatomical structures that are inflamed. It is further subdivided into acute, recurrent or chronic, based on the time course of the disease.17

AAU represents the majority of cases of uveitis in patients with rheumatic diseases. This condition involves a sudden onset episode of inflammation of the iris or the anterior ciliary body that is present for less than 3 months.17 Ankylosing spondylitis is the most frequent underlying rheumatic disease causing uveitis, occurring in 20–30% of patients.17 AAU is also associated with other disease entities, such as reactive arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease and psoriatic arthritis. Patients with systemic disease affected by AAU are generally aged between 30 and 40 years, and most test positive for human leukocyte antigen-B27.18

Patients with AAU often present with ocular pain, an acute onset of photophobia, excessive lacrimation, ocular injection and blurred vision (Box 4, Box 5). The symptoms tend to be unilateral and recurrent, occasionally in the contralateral eye. Attacks can last 2–3 months; residual visual impairment is uncommon when treated early.19 Loss of vision in patients with AAU develops as a result of complications, including cataract formation (7–28%),18 macular oedema (up to 11%),20 secondary glaucoma and the development of chronic uveitis.19

AAU is best diagnosed with slit lamp examination, warranting prompt referral to an ophthalmologist when the diagnosis is suspected. The pupil may be poorly reactive and the anterior chamber may show signs of inflammation, including the presence of cells, flare and occasional fibrin (inflammatory debris) within the chamber. In severe cases, there may be evidence of hypopyon. The ciliary blood vessels surrounding the limbus are usually dilated.

The mainstay of treatment is topical glucocorticoids, such as 1% prednisolone acetate. The frequency of the dose depends on the intensity of inflammation present, determined by slit lamp examination.17 Dilating drops are used to relieve pain and prevent iris–lens adhesions.

Sjögren syndrome

Sjögren syndrome is a slowly progressing, immune-mediated inflammatory disease targeting the exocrine glands. It leads to the replacement of functional epithelium with lymphocytic infiltrates, resulting in a dry mouth and dry eyes. Sjögren syndrome is classified as primary when it occurs in the absence of other connective tissue or autoimmune disease, or secondary when it accompanies another disease. About 60% of cases are secondary. It affects women more than men (9:1 ratio), often in their fourth or fifth decade of life.21 Rheumatoid arthritis is the most common underlying rheumatic disease, affecting 10–33% of patients,22,23 followed by systemic lupus erythematosus, affecting up to 9.2% of patients.24 Associations have also been reported in patients with scleroderma and polymyositis.25

The clinical features of Sjögren syndrome are dry eyes and mouth. The discomfort of dry mouth is often associated with difficulty swallowing and speaking, while the lack of tears leads to damage to the conjunctival epithelium over the cornea and globe. This typically presents with dilation of the conjunctival vessels and an irregular appearance to the cornea. Patients may present with dry, gritty or burning eyes, which should prompt consideration of the diagnosis. The average time between the onset of symptoms and the diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome is 10 years,26 largely because the symptoms are considered minor or vague or because they mimic those of other autoimmune diseases. Diagnosis can be made by the combination of the symptoms of dry eyes and mouth, a positive Schirmer test result and positive autoimmune screening (anti-SSA and anti-SSB) blood test results.27 Further characterisation with salivary gland biopsy can be sought if all the above criteria are not satisfied.27

Early diagnosis and treatment are essential for optimal management of Sjögren syndrome. Treatment comprises symptomatic relief through topical replacement lubrication and anti-inflammatory agents, as well as treatment of the underlying systemic disease where appropriate.28

Ocular side effects of drugs used for treating rheumatic disease

The eyes are highly vascular organs with a relatively small mass, making them particularly susceptible to toxic substances that circulate in the blood stream. The fundamental concepts in managing ocular side effects of drugs used in treating rheumatic disease are recognition of the early signs of eye toxicity, withdrawal of the offending agent and referral to an ophthalmologist. These side effects are summarised in Appendix 2.

Corticosteroids

The most studied ocular complications from corticosteroid use are the induction of cataracts and the increase in ocular pressure causing glaucoma.29 Patients treated with oral prednisolone doses of less than 10 mg per day for 1 year have a negligible chance of developing cataracts. In patients taking oral corticosteroids, the yearly incidence of corticosteroid-induced cataracts ranges from 6.4% to 38.7%.30

Glaucoma is thought to develop in patients taking corticosteroids due to glycosaminoglycan and water accumulation in the trabecular meshwork.29 If intraocular pressure is elevated in patients who recently began steroid therapy, the steroids need to be tapered down as rapidly as possible. Current guidelines from the National Health and Medical Research Council recommend survey for glaucoma through regular eye health checks, particularly in patients older than 50 years who have ongoing steroid use.31

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Ocular side effects from non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are rare. Long term use of indomethacin has been associated with cases of corneal opacities and blurred vision.32 Corneal changes diminish or disappear within 6 months of ceasing the offending agent. Celecoxib has been associated with cases of conjunctivitis and blurred vision that resolve rapidly on ceasing the medication.33

Sulfonamides

Patients taking sulfonamides for rheumatoid arthritis, ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease are at an increased risk of developing acute transient myopia and acute angle closure glaucoma. These complications have been reported in up to 3% of patients, and often resolve with supportive treatment and withdrawal of the offending agent.34

Biological drugs

Patients taking abatacept report ocular side effects in less than 1% of cases. These include non-specific symptoms such as blurred vision, eye irritation, allergic conjunctivitis and visual disturbances.33

Antimetabolites

Patients taking methotrexate will have a reduction in ocular side effects when it is combined with regular folate supplements. Methotrexate-related ocular toxicities include periorbital oedema, ocular pain, blurred vision, photophobia, conjunctivitis, blepharitis and decreased reflex tear secretion.33

Bisphosphonates

There have been several reports linking bisphosphonate therapy with ocular inflammation, particularly causing uveitis and scleritis. If inflammatory eye disease develops after starting bisphosphonate therapy, discontinuation of the therapy is recommended.33

Antimalarial agents

Hydroxychloroquine sulfate, which has a far lower incidence of retinal toxicity than older quinolones, is the quinolone agent of choice for treating autoimmune disease. Hydroxychloroquine may cause ocular toxicity, including keratopathy, ciliary body involvement, lens opacities and retinopathy, of which retinopathy is of greatest concern.35 While the incidence of true hydroxychloroquine retinopathy is extremely low, the risk increases to close to 1% after 5–7 years of use.36 As such, annual screening by an ophthalmologist is recommended by the American Academy of Ophthalmology for patients who have been taking hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for more than 5 years.36 Patients should also have a baseline fundus examination and should be informed of the risk of toxicity.36

Conclusion

The development of ocular symptoms in patients with systemic diseases is common, and it is important for physicians to be aware of which symptoms require immediate intervention and ophthalmologist referral to prevent loss of vision. Insight into the epidemiology, clinical presentation, common complications and basic treatment regimens of these conditions enables clinicians to more rapidly identify them in clinical practice.

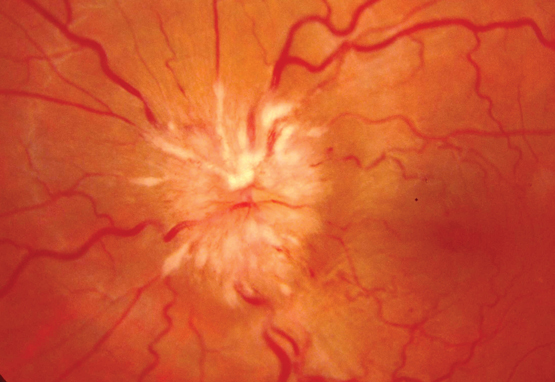

Box 1 –

Fundoscopic appearance of retinal vasculitis, showing retinal haemorrhages, cotton wool spots and perivascular hard exudates

Box 2 –

Crescent-shaped corneal ulcer with neovascularisation and injection of ciliary blood vessels

Box 3 –

Necrotising scleritis with exposure of the underlying uvea and associated area of scleral necrosis

A visual summary for medical students and physicians

A mind map is a graphical organisation of ideas, a “visual thinking tool” for structuring information, which psychologist Tony Buzan (www.tonybuzan.com) has claimed improves memory and understanding.

In Mindmaps in ophthalmology, Abhishek Sharma, a medical and surgical retinal specialist at the Queensland Eye Institute, uses this technique to “provide an overview of clinical ophthalmology” problems. Sharma wrote the book during his training for Fellowship of the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists, and there is no comparable publication.

Ideas are arranged in “spider charts”, with the problem in the centre of the page and deductions spreading out radially in a hierarchical relationship. Moreover, the branches are colour coded for better identification of the flow. When a provisional diagnosis is reached at the edge of the page, a new page is started with this in the centre for investigations and then another for treatment options. For example, optic nerve dysfunction on page 81 covers examination. If there is optic nerve swelling, the reader has to go to page 87 for possible diagnoses and to subsequent pages for investigation and treatment of the diagnosis. This differs from flow charts, which are linear, in that mind maps encourage exploration of many possible alternatives.

Mindmaps in ophthalmology is a useful summary or revision tool for students and ophthalmologists; however, it must be used in conjunction with conventional textbooks, which give deeper understanding of the topics.

Light-based epilation device-related injury to the cornea

Clinical record

In recent years, there has been a surge in the commercial availability of light-based epilation devices, developed for cosmetic purposes as a means of long-lasting hair removal.1 Intense pulsed light (IPL) therapy is commonly used for “laser” hair removal. Depending on commercial variation, devices for IPL delivery use a polychromatic, non-coherent light to produce wavelengths ranging from 515 to 1200 nm. This light is able to penetrate and induce a selective photothermolytic reaction in hair follicles.2 We discuss the case of a woman with accidental corneal exposure to IPL during epilation of her cheek while wearing inappropriate ocular protection.

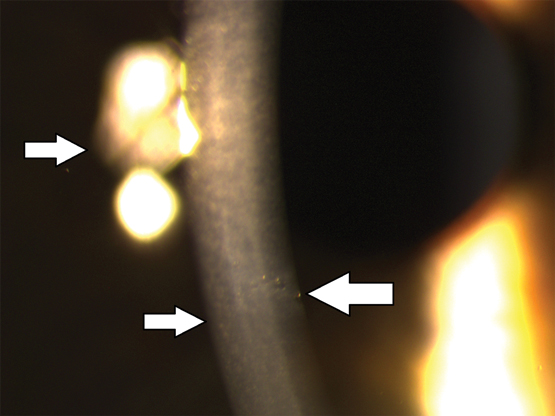

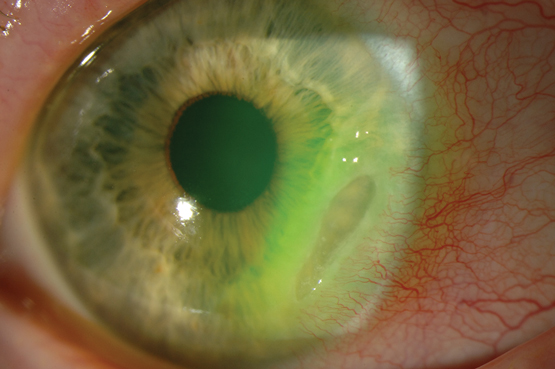

A 24-year-old woman presented with a sharp pain in her right eye following exposure of the eye to IPL during facial hair epilation. She reported that during epilation of her cheek, the IPL probe slipped in the operator’s hand, knocking off the plastic protective goggles she was wearing. Her past ocular history was the use of daily disposable contact lenses to correct myopia. There was no family history of ocular disease. On examination, she achieved 6/6 best corrected in each eye, and ocular tensions were within normal limits. The right cornea had five small lesions of about 0.2 mm in size at the level of the Descemet membrane. The rest of the ocular examination was within normal limits. On review at 4 months (Figure) and 2 years, the lesions had not changed.

We performed a literature search on PubMed and MEDLINE, using search terms “laser eye injury”, “laser corneal injury”, “hair epilation therapy”, “ocular complications” and “laser ocular complications”. We found no other reported cases of direct corneal damage from IPL. In our patient, permanent corneal scarring resulted without an effect on vision. Our patient was left with five circular corneal lesions. A differential diagnosis of posterior polymorphous dystrophy was excluded based on the appearance of the lesions, normal appearance of the endothelium, normal left eye and lack of a family history. In our patient, the cornea lesions were not vesicular, and were well demarcated, circular and of uniform size. Further, there was no sign of corneal stromal oedema.

During IPL, the possibility of direct corneal damage has been highlighted in the literature,1 and indirect corneal injury has been reported.2,3 A case of corneal pigment deposition resulted from a coloured lens worn during IPL therapy to the face without an effect on vision.3 IPL hair removal is now widely available and home-based treatments are emerging. The lack of literature on corneal damage from IPL may be because many devices filter out wavelengths below 450 nm. This would theoretically minimise the risk of photochemical damage to the cornea and other ocular structures.1 Although IPL is the most common means of laser hair removal, it can also be carried out with alexandrite or diode lasers. Indeed, nuclear cataract and iris atrophy have been reported as complications of diode laser therapy.4

Increasingly, devices for hair removal are being used around the eye. Indeed IPL is now being used for patients with dysfunction of the meibomian gland of the eyelid, as it may improve the tear film and reduce dry eye symptoms.5 Our case and reports in the literature highlight that patients may be at risk of ocular complications, particularly if staff are not adequately trained in the use of the equipment and appropriate protective eye wear is not worn. Although there are no current international safety eyewear standards in place for IPL devices, the majority of IPL manufacturers provide eyewear with an optical density of 3–5. Such eyewear adheres to the harmonised American and European welding eyewear standards.1 We recommend that patients be counselled as to these risks and that efforts be made to collate cases of ocular damage associated with cosmetic lasers used around the face.

Lessons from practice

-

Intense pulsed light (IPL) therapy, an increasingly popular cosmetic and eyelid treatment, has the potential to cause permanent ocular complications.

-

All operators of IPL therapy and other cosmetic laser therapies should be adequately trained in the proper use of equipment and the necessity for protective gear.

-

Protective eyewear with the appropriate optical density as prescribed by the harmonised American and European welding eyewear standards should be worn during IPL and other cosmetic laser therapy.

-

A patient or staff member suspected of having had unprotected exposure to lasers should be promptly referred to an ophthalmologist for review.

Central visual loss following a motor vehicle accident: traumatic airbag maculopathy

Clinical record

A 62-year-old woman was the driver of a car travelling at 60 km per hour when it collided with a stationary truck with subsequent airbag deployment. She wore no spectacles and her seatbelt was fastened at the time of the accident. She was initially assessed in the emergency department (ED) and subsequently discharged. Four days after the incident, she was referred by her general practitioner to the ED as she had persistent blurred central vision. The patient did not report any neurological symptoms. Her past ocular history included blunt trauma to the right eye from a snowball as a teenager.

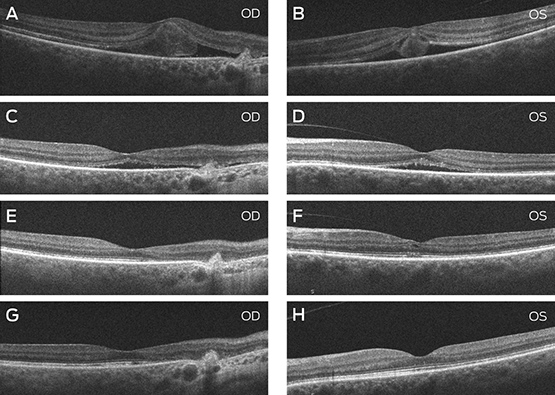

Her best corrected visual acuity was 6/15 in the right eye and 6/24 in the left eye. No acute anterior segment pathology was present. Dilated fundus examination revealed several small intraretinal haemorrhages, but no retinal tears were found. A spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) scan showed subretinal fluid as well as hyper-reflective material at the fovea bilaterally (right more so than left).

Subsequent macular SD-OCT scans demonstrated bilateral resolution of the subretinal fluid over a period of 3 months with associated improvement of her vision to 6/12 in each eye (Box).

Our literature review on the PubMed database using the keywords airbag, trauma, macular and maculopathy yielded 12 similar cases, but none from Australia. We therefore believe this to be the first report of an Australian case of central visual loss from traumatic airbag maculopathy (TAM) without apparent external injuries. Despite saving lives, airbags have been associated with a range of ocular trauma specific to their deployment, including corneal injuries, hyphaema, intraocular haemorrhages, retinal tears and detachments.1 Other modifiable risk factors that affect the severity of the eye injuries include unfastened seatbelt, wearing spectacles and close proximity to the steering wheel.1 Newer airbags have reduced inflation force, which decreases overt manifestations of direct blunt ocular trauma; however, as our report shows, they may cause a separate pattern of occult ocular injury.

The postulated cause of the specific injury of TAM relates to the acceleration–deceleration forces resulting in retinal dehiscence.2,3 The forces involved may cause blunt trauma to the ocular tissue, due to the airbag inflating in one direction and the head moving in the opposite direction at high velocity. The traumatic mechanism causes a disruption of the connecting cilia of cones and rods in the outer segment.4

One reported case of TAM described immediate unilateral blurred central vision with no other ocular injuries, and an SD-OCT scan demonstrated foveal detachment.5 Another report described two cases of post-traumatic unilateral maculopathy with serous retinopathy on SD-OCT imaging.2,5 All three cases showed resolution of foveal subretinal fluid over 4 weeks, consistent with the pattern of resolution seen in this case; however, full retinal architecture was restored within 12 weeks. Despite substantial visual improvement and return to a normal anatomical appearance, patients can report ongoing paracentral scotomas, which are detectable only on electrophysiology testing and suggest a persisting disruption to retinal function.5 The time frame for the resolution of the subretinal fluid is important as it may coincide with the resolution of ocular injuries, such as hyphaemas or vitreous haemorrhages, which may obscure the diagnosis of the macular pathology. Therefore, clinicians need to consider TAM in patients with persisting scotomas and obtain an electrophysiology study in the context of normal clinical and SD-OCT scan findings.

In summary, significant sight-threatening ocular injuries related to airbags can occur despite the lack of apparent external trauma to the eye. The visual symptoms and visual acuity should be specifically assessed in these patients. A prompt referral to an ophthalmology service is paramount to allow detailed ocular assessment and detection of subtle maculopathy that may have long term visual consequences.

Lessons from practice

-

New airbag technology has resulted in reduced external ocular injuries.

-

Subtle maculopathy resulting from dehiscence forces is a newly identified clinical entity that has unknown long term consequences.

-

Ophthalmology referral may be required even when there is no apparent external ocular injury.

-

Assessment for sight-threatening conditions, including traumatic airbag maculopathy, is required in symptomatic patients with blurred vision following airbag deployment.

Box –

A and B: SD-OCT scan of the maculae through the fovea at presentation, 4 days after a motor vehicle accident. OD: foveal subretinal fluid with a choroidal scar nasally from a previous injury. OS: foveal subretinal and intraretinal fluid. C and D: SD-OCT scan of the maculae 2 weeks after presentation. OD: residual subretinal fluid. OS: scan 2 weeks after presentation showed residual subretinal fluid. E and F: SD-OCT scan of the maculae 4 weeks after presentation. OD: the retinal architecture is largely restored. OS: residual abnormalities are noted in the inner and outer retinal structure. G and H: SD-OCT scan of the maculae 3 months after presentation. OD: retinal atrophy nasal to the fovea is noted and consistent with a previous choroidal rupture. OS: the inner and outer retina is structurally restored.

Central retinal venous pulsations

Diagnosing raised intracranial pressure through ophthalmoscopic examination

The ophthalmoscope is one of the most useful and underutilised tools and it rewards the practitioner with a wealth of clinical information. Through illumination and a number of lenses for magnification, the direct ophthalmoscope allows the physician to visualise the interior of the eye. Ophthalmoscopic examination is an essential component of the evaluation of patients with a range of medical conditions, including diabetes mellitus, systemic hypertension and conditions associated with raised intracranial pressure (ICP). The fundus has exceptional clinical significance because it is the only location where blood vessels can be directly observed as part of a physical examination.

Optic disc swelling and central retinal venous pulsations are useful signs in cases where raised ICP is suspected. Both signs can be obtained rapidly by clinicians who know how to recognise them. Although optic disc swelling supports the diagnosis of raised ICP, the presence of central retinal venous pulsations may indicate the contrary.

In the standard technique for direct ophthalmoscopy, the patient is positioned in a seated posture and asked to fix their gaze on a stationary point directly ahead. Pupillary dilation, removal of the patient’s spectacles and dim room illumination usually aid the examination. To start examining the patient, set the ophthalmoscope dioptres to zero — alternatively, a suitable setting would be the sum of the refractive errors of the patient and the examiner. Use the right eye to examine the patient’s right eye and vice versa. Using a slight temporal approach facilitates the identification of the optic disc, which also minimises awkward direct facial contact with the patient. Examine the red reflex at just under arm’s length. A pale or absent red reflex may suggest media opacity, such as a cataract. Next, on approaching the patient and obtaining a clear view of a retinal vessel, follow its course toward the optic disc. The presence or absence of venous pulsations should be appreciable (see the video at www.mja.com.au; pulsations of the central vein are clearly visible at the inferior margin of the optic disc). These pulsations, usually of the proximal portion of the central retinal vein, are most readily identified at the optic disc. The examination of the fundus should be concluded by visualisation of the four quadrants of the retina and examination of the macula.

Central retinal venous pulsations are traditionally attributed to fluctuations in intraocular pressure with systole, although this is may be an incomplete explanation.1 Patients with central retinal venous pulsations generally have cerebrospinal fluid pressures below 190 mmHg.2 Based on the results of Wong and White,3 the positive predictive value for retinal venous pulsations predicting normal ICP was 0.88 (0.87–0.9) and the negative predictive value was 0.17 (0.05–0.4).

This is important when considering lumbar puncture and when neuroimaging is not available. A limitation of this sign is that about 10% of the normal population4 do not have central retinal venous pulsations visible on direct ophthalmoscopy.4 The absence of central retinal venous pulsations does not, by itself, represent evidence of raised ICP; some patients with elevated ICP may still have visible retinal venous pulsations.

Papilloedema (optic disc swelling caused by increased ICP) may develop after the loss of retinal venous pulsations. This change in the appearance of the optic disc and its surrounding structures may be due to the transfer of elevated intracranial pressure to the optic nerve sheath. This interferes with normal axonal function causing oedema and leakage of fluid into the surrounding tissues. Progressive changes include the presence of splinter haemorrhages at the optic disc, elevation of the disc with loss of cupping, blurring of the disc margins, and haemorrhage. In later stages, there is progressive pallor of the disc due to axonal loss. A staging scale, such as that of Frisén,5 can be used to reliably identify the extent of papilloedema (Box).

AMA Federal Council elections

Several vacancies on the AMA Federal Council will be put to the vote following the receipt of rival nominations.

The Returning Officer, Anne Trimmer, has announced that electronic ballots will be held for each of five contested positions on the Council, which is the AMA’s peak policy making body.

A ballot of members in relevant Federal Voting Groups or Areas will be held for the following positions next month:

Contested vacancies

Area Representatives

VICTORIA:

- · Dr Anthony Bartone

- · Dr Umberto Boffa

QUEENSLAND:

- · Dr Wayne Herdy

- · Dr Richard Kidd

Specialty Groups

GENERAL PRACTITIONERS:

- · Dr Anthony Bartone

- · Dr Richard Kidd

PAEDIATRICIANS:

- · Dr Paul Bauert

- · Dr Kathryn Browning Carmo

PSYCHIATRISTS:

- · Dr Steve Kisely

- · A/Professor Robert Parker

Filled vacancies

Fifteen other positions on the Council have been filled without contest, and Ms Trimmer has declared the following members elected:

Area Representatives

NSW/ACT: A/Professor Saxon Smith

SA/NT: Dr Christopher Moy

TAS: Dr Helen McArdle

WA: Dr Michael Gannon

Specialty Groups

ANAESTHETISTS: Dr Andrew Mulcahy

DERMATOLOGIST: Dr Andrew Miller

EMERGENCY PHYSICIANS: Dr David Mountain

OBSTETRICIANS AND GYNAECOLOGISTS: Dr Gino Pecoraro

ORTHOPAEDIC SURGEONS: Dr Omar Khorshid

PATHOLOGISTS: Dr Beverley Rowbotham

PHYSICIANS: A/Professor Robyn Langham

RADIOLOGISTS: Professor Makhan (Mark) Khangure

SURGEONS: A/Professor Susan Neuhaus

Special Interest Groups

DOCTORS IN TRAINING: Dr John Zorbas

PUBLIC HOSPITAL PRACTICE: Dr Roderick McRae

Open vacancies

Nominations were not received for three positions, and Ms Trimmer has called for expressions of interest from members. The positions are:

- Private Specialist Practice

- Rural Doctors

- Ophthalmology

Members interested in filling these vacancies are asked to contact Ms Trimmer at: atrimmer@ama.com.au

A case of bilateral endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis from Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteraemia

Clinical record

A 55-year-old woman was admitted to an orthopaedic unit of a metropolitan hospital in Australia with right shoulder septic arthritis. She had been experiencing 3 days of right shoulder pain, fevers, rigors and delirium. These occurred in the context of a right rotator cuff repair 3 months previously. Her medical history included hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and an L4-S1 spinal fusion for lumbar spine degeneration. Her medications included hydrochlorothiazide, olmesartan and atorvastatin.

On examination, she was febrile with a temperature of 38.9°C, with a painful, erythematous and swollen right shoulder with movement limited by pain. Her chest and abdominal examinations were normal. Her relevant admission blood test results were white cell count, 30 × 109/L (reference interval [RI], 4–11 × 109); neutrophil count, 21.9 × 109 (RI, 2–8 × 109); and C-reactive protein level, 438 mg/L (RI, 0–5 mg/L). Platelet, haemoglobin, uric acid and blood sugar levels were all normal. Her shoulder and chest x-rays were unremarkable. Several sets of blood cultures as well as a shoulder aspirate showed gram-positive cocci and she was empirically commenced on intravenous (IV) flucloxacillin 2 g four times a day and vancomycin 1.5 g twice daily.

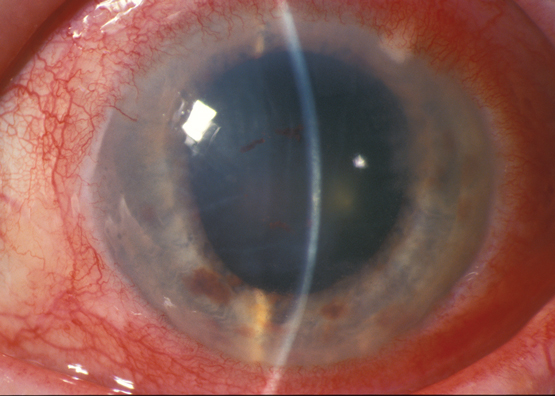

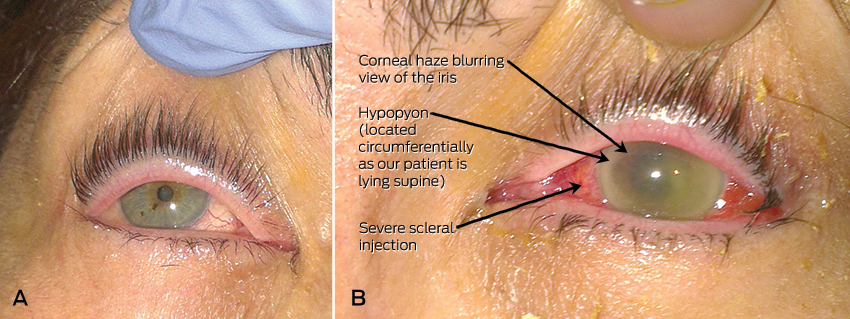

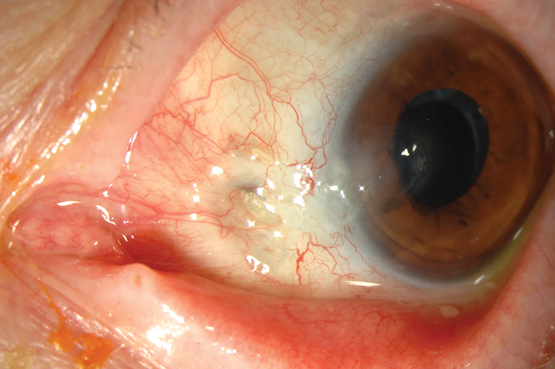

Shortly after admission, she revealed that she had been experiencing 3 days of blurred vision and pain in her left eye. Further history revealed that aside from mild myopia, her vision was previously normal and she had never undergone any ophthalmic procedures. Her right eye was asymptomatic and appeared slightly injected but otherwise normal on initial assessment (Figure, A). However, her left sclera was severely injected, and the pupil was fixed and mildly dilated with corneal and anterior chamber haze and a circumferential hypopyon (Figure, B). Visual acuity (VA) was 6/12 in her right eye, but only hand movements were appreciated in her left eye. Fundoscopy was not possible on the left eye owing to the severity of the corneal haze; however, in the right eye, fundoscopy showed a vitreous haze.

An urgent assessment by an ophthalmologist found that she had bilateral endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis. Despite appearing mostly unremarkable on external inspection, the right eye was deemed to be in the early stages of infection owing to the presence of vitreous haze on fundoscopy. After aqueous humour samples were taken, she was given bilateral intravitreal antibiotic injections of 1 mg vancomycin and 2 mg ceftazidime. This was followed up with intravitreal injections of 1 mg vancomycin every second day for three further doses. The cultures from her shoulder, blood and eyes all grew Streptococcus pneumoniae. Her antibiotics were changed to IV benzylpenicillin and vancomycin; IV azithromycin was also added, as evidence has shown that it has a survival benefit in S. pneumoniae infections.1 Further investigations performed to exclude immunosuppression and locate the source of the septicaemia included HIV, tuberculosis and hepatitis serology; glycated haemoglobin testing; vasculitic screening; a transthoracic echocardiogram; computed tomography of the chest, abdomen and pelvis to look for malignancy or abscesses; and a magnetic resonance imaging scan of her lumbosacral spine to exclude infection of the implants from her spinal fusion. The results of these tests were unremarkable and no cause was found to explain the S. pneumoniae septicaemia.

Twelve days after admission, she was transferred to another centre with a vitreoretinal unit, where she underwent a left vitrectomy to debride the posterior chamber of her eye. Unfortunately, the vision in her left eye only made a small recovery and, 6 months later, the VA was limited to counting fingers. Fortunately, VA in her right eye remained at its baseline and she has been managing well in the community.

Bacterial endophthalmitis is an infection of the eye involving the aqueous and/or vitreous humour. It is an ophthalmic emergency and requires urgent treatment to prevent permanent blindness. The vast majority of cases are due to exogenous inoculation of microbes into the eye via trauma, surgery, intravitreal injections or an invasive corneal infection. Rarely, in 2–6% of cases, it can occur from haematogenous spread of organisms to the eye, which is referred to as endogenous or metastatic endophthalmitis. Endogenous spread is associated with immunosuppressive predisposing factors such as diabetes or malignancy in 90% of cases.2

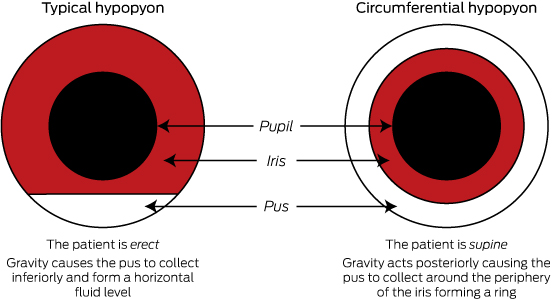

Patients usually experience 12–24 hours of eye pain and decreasing vision. They are rarely systemically unwell. However, patients with the endogenous variant are usually unwell from the underlying bacteraemia. On examination, there is often conjunctival injection or oedema of the cornea. VA will be decreased. Slit-lamp examination of the anterior chamber may show cells and flare (small floating particles and a generalised haziness, respectively, in the anterior chamber representing inflammation). As in this patient, it may be also be associated with a hypopyon. Hypopyon is pus in the anterior chamber of the eye which will collect inferiorly and form a horizontal layer in an erect patient (Figure, B shows a circumferential hypopyon in our patient as she was supine at the time she was photographed; the Box highlights the difference between hypopyon in erect and supine patients). On fundoscopy, there is usually poor visualisation of the retina secondary to vitreous haze.2,3 The diagnosis can be confirmed via aqueous or vitreous culture, but it should be noted that history and examination are the main diagnostic tools, as a negative culture cannot reliably exclude the condition.4

Bacterial endophthalmitis is usually exogenous and postoperative. It is most commonly caused by coagulase-negative staphylococci (the most common normal flora of the ocular surface).5 The organisms for the endogenous form depend on the underlying infection. A major study showed only 30% of patients with streptococcal endophthalmitis had a final VA of 6/30 or better, which is worse than for Staphylococcus aureus, gram-negative bacteria (50% for both) and coagulase-negative staphylococci (80%).6 Regardless of the organism involved, the strongest indicator of visual prognosis is VA at presentation.5

Treatment of endophthalmitis requires prompt referral to an ophthalmology team. Treatment of bacterial endophthalmitis involves intravitreal antibiotic injections as the intravenous route does not deliver sufficient concentrations to the relatively avascular posterior chamber of the eye. Empirical therapy is usually vancomycin with ceftazidime or amikacin. This is often combined with vitrectomy, which debrides the vitreous, reducing the bacterial load. Patients should also be treated with systemic antibiotics for sufficient duration to clear the underlying infection.7

Bilateral endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis is very rare, with one study estimating that only around 12% of patients with endophthalmitis had both eyes infected.2 A rare bilateral case like ours, where one eye is severely infected and the other is in the early stages of infection, serves to demonstrate the importance of early diagnosis, as once vision has been lost it is far less likely to return. Further, our case is unusual in that no immunosuppression was found in a relatively young patient.

Lessons from practice

-

Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis can rapidly cause blindness and should be considered in all bacteraemic patients with decreased visual acuity or ocular pain.

-

Risk factors include diabetes, malignancy and immunosuppression.

-

Early diagnosis is important as visual acuity on diagnosis is the strongest indicator of final visual prognosis.

-

Early ophthalmology involvement and intravitreal antibiotic injections are essential, as intravenous therapy alone will not deliver adequate concentrations to the relatively avascular vitreous.

Orbital myositis secondary to statin therapy

A 45-year-old man presented with a 3-month history of diplopia and pain on left downgaze, increasing left upper lid oedema, and erythema. Eye movements were full and visual acuity and intraocular pressure normal. His regular medications, both commenced 4 months before presentation, were simvastatin (20 mg/day) and aspirin (100 mg/day). A complete blood count, thyroid function and auto-antibodies, inflammatory markers and creatine kinase were all unremarkable, as was an autoimmune screen. Orbital computed tomography showed left medial rectus and superior oblique enlargement.

Simvastatin was ceased, and all symptoms resolved within 3 weeks. Diplopia recurred 4 weeks after a rechallenge with 10 mg simvastatin daily, and resolved almost immediately after withdrawing the statin. The man subsequently elected to control his cholesterol levels with lifestyle modifications.

Orbital myositis is inflammation of one or more extraocular muscles, characteristically presenting with diplopia and orbital pain exacerbated by eye movement. Restriction of eye movement, exophthalmos, conjunctival inflammation and erythema may occur;1 imaging indicates muscle and tendon enlargement. It is usually idiopathic, but can occur in association with a range of inflammatory conditions, including sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Crohn’s disease and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis.1

Statins are usually well tolerated medications, but myopathy occurs in 1%–5% of participants in clinical trials, and in 10%–15% of patients in observational studies.2 Statins can affect the extraocular muscles, and orbital myositis should be considered in patients experiencing orbital symptoms during statin treatment.3 The metabolic requirements of extraocular muscles are enormous, but their glycogen content is limited, which may make them more vulnerable to the GTP depletion and myopathy associated with statin use.4 Such patients may present to any of a range of clinicians, and lack of awareness of this complication can mean that cessation of statin therapy is not tried, or that inappropriate treatment is given.

We reviewed VigiBase (the World Health Organization global individual case safety reports database) and two subsets of this adverse drug reaction database (the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency [United Kingdom] and the Therapeutic Goods Administration [Australia]) for all reported ocular complications associated with atorvastatin, simvastatin, rosuvastatin and pravastatin. These databases contained a total of 452 reports suggestive of orbital myositis (Box), including subjective and objective symptoms and signs, and one instance specifically described as an “extraocular muscle disorder”. The databases rarely record dechallenge or rechallenge data, nor do they record relevant investigations and clinical follow-up data. However, as most complications are unreported by patients and their clinicians, the true incidence of side effects is likely to be far higher than that reported.

We would encourage others to use scales such as the Naranjo algorithm, which incorporates important data such as rechallenge and the results of investigations, to calculate adverse drug reaction probabilities.5 Using this scale, our case achieved a score of 9, indicating a “definite” adverse drug reaction.

Box –

Summary of the 452 adverse events recorded in event notification databases

|

|

Diplopia |

Exophthalmos |

Ophthalmoplegia |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

TGA (15 reports) |

|||||||||||||||

|

Atorvastatin |

7 |

— |

— |

||||||||||||

|

Simvastatin |

5 |

— |

— |

||||||||||||

|

Rosuvastatin |

2 |

— |

— |

||||||||||||

|

Pravastatin |

1 |

— |

— |

||||||||||||

|

MHRA (30 reports) |

|||||||||||||||

|

Atorvastatin |

8 |

1 |

— |

||||||||||||

|

Simvastatin |

11 |

1 |

— |

||||||||||||

|

Rosuvastatin |

— |

1 |

— |

||||||||||||

|

Pravastatin |

7 |

1 |

— |

||||||||||||

|

WHO (407 reports) |

|||||||||||||||

|

Atorvastatin |

107 |

3 |

22 |

||||||||||||

|

Simvastatin |

95 |

— |

30 |

||||||||||||

|

Rosuvastatin |

49 |

— |

18 |

||||||||||||

|

Pravastatin |

69 |

1 |

13 |

||||||||||||

|

Total |

361 |

8 |

83 |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

TGA = Therapeutic Goods Administration Database of Adverse Event Notifications (Australia); MHRA = Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (United Kingdom); WHO = VigiBase, World Health Organization, Uppsala Monitoring Centre (Sweden). |

|||||||||||||||

Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess complicated by endogenous endophthalmitis: the importance of early diagnosis and intervention

Clinical record

A 51-year-old man presented to the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital with 3 days of progressive visual loss and pain in the left eye, and a 6-hour history of painless visual loss in the right eye. He reported a 1-week history of fever, night sweats, sore throat and a non-productive cough. The man was systemically well, with no features of sepsis or abdominal pain.

His only medical history was for hypercholesterolaemia. He was Malaysian, but had lived in Australia for 10 years. He had recently travelled to Malaysia and Vietnam.

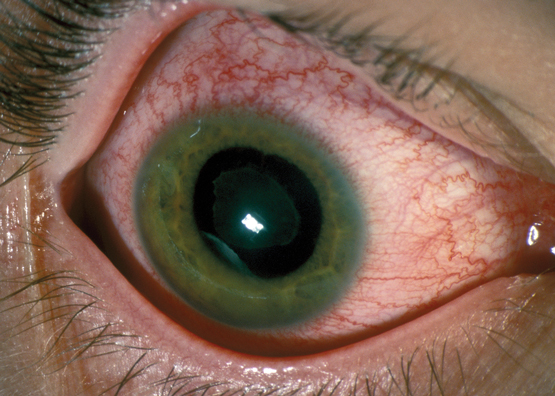

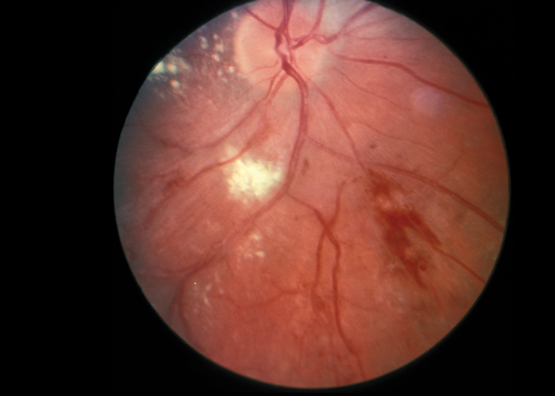

Visual acuity (VA) was hand movements in the left eye and 6/12 in the right. He had a left relative afferent pupillary defect and bilateral hypopyon. Vitritis limited posterior segment examination. The left eye had lid swelling, conjunctival chemosis, proptosis, and computed tomography (CT) showed evidence of scleritis (Figure, A).

White cell count (26 × 109/L; reference interval [RI], 4.0–11.0 × 109/L) and C-reactive protein levels (199 mg/L; RI <5 mg/L) were both elevated; liver function tests were deranged, with evidence of cholestasis. Liver ultrasonography revealed a 5.3 cm abscess in segment VII. A CT scan showed two abscesses: a 5.0 × 5.7 cm abscess in segments V/VIII and a 3.3 × 5.1 cm abscess in segment VII, with cholelithiasis and segmental thrombosis of the right hepatic vein (Figure, B). The results of blood cultures were negative.

VA in the right eye deteriorated to counting fingers over a 24-hour period, and endogenous Klebsiella pneumoniae endophthalmitis was suspected. The patient received systemic ceftriaxone; bilateral intravitreal vancomycin, ceftazidime and dexamethasone; and oral and topical corticosteroid therapy. K. pneumoniae was cultured from ultrasound-guided drainage of one liver abscess and from urine. Repeated vitreous samples included polymorphonuclear leukocytes, but no bacteria could be cultured. Hepatic vein thrombosis was treated with therapeutic enoxaparin and, later, rivaroxaban.

Pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) was performed in the right eye 2 days after presentation, and a superotemporal subretinal abscess was noted. Vision initially improved to 6/24, but deteriorated to hand movements 2 days after the operation, presumably following rupture of the abscess. A second PPV was performed, and the abscess was drained. A rhegmatogenous retinal detachment was managed intraoperatively with endolaser and silicone oil (Figure, C). The right eye received four doses and the left eye five doses of intravitreal vancomycin, ceftazidime and dexamethasone.

The left eye underwent a two-stage PPV, with the first surgery 4 days after presentation. An inferior subretinal abscess was drained during the second PPV (Figure, C and D). An associated rhegmatogenous retinal detachment was treated with endolaser and silicone oil.

Both eyes settled well (Figure, E and F). The retinae remained attached bilaterally under oil, and best-corrected VA had improved to 6/12 in the right eye and 6/24 in the left eye at the 1-month follow-up.

Endophthalmitis refers to inflammation of the intraocular space, and is predominantly of infectious aetiology. It is usually exogenous and may complicate intraocular surgery, penetrating trauma or corneal ulceration. Around 2%–8% of cases occur via endogenous spread, often in the context of immunosuppression, diabetes or injecting drug use.1

In Australia, fungal organisms cause 65.9% of endogenous endophthalmitis, while gram-negative organisms cause 19.5%.1 In East Asia, there is an increasing incidence of disease caused by gram-negative organisms, with Klebsiella pneumoniae now the most common cause of endogenous endophthalmitis.2–4 K. pneumoniae is a known cause of pyogenic liver abscess in southeast Asia, with metastatic spread of infection occurring in 3.5%–20% of cases and endogenous K. pneumoniae endophthalmitis (EKPE) in 3%–7.8% of cases.3

EKPE has an extremely poor prognosis.2–5 Retinal damage occurs rapidly following irreversible necrosis of the retinal photoreceptor layer and the associated subretinal abscess formation.1–7 Final visual outcomes of hand movements or worse are reported in 66%–78% of cases,3,7 no perception of light in 57.8%–62%,7,8 and evisceration or enucleation in 26.8%–75% of patients;1,8 in one report, three cases of EKPE required enucleation despite appropriate intensive antibiotic treatment.6

The poor prognosis is exacerbated by delayed diagnosis, particularly in patients who, because of overwhelming systemic illness, are unable to describe visual symptoms.2 Further significant predictors of a worse prognosis include poor initial visual acuity3 and the presence of hypopyon at presentation.8

In rare cases, EKPE may be the first manifestation of K. pneumoniae infection.3 EKPE is usually unilateral, but bilateral ocular involvement is reported in up to 26% of patients.1 Diabetes is a risk factor for EKPE.2,5 There is no general consensus about the most appropriate treatment for EKPE.

It has been suggested that pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) reduces intraocular bacterial and inflammatory load in EKPE and aids the penetration of intravitreal antibiotics.2,6 The best visual outcomes are seen in patients who undergo surgery early.4 In a Korean report about seven patients (10 eyes) with EKPE, early PPV was performed on eight eyes and delayed PPV on two. Operative findings included extensive retinal necrosis with subretinal abscess formation and dense vitritis. Five eyes maintained a final VA of counting fingers or better, VA in two eyes improved to 6/19 and 6/38; no enucleations or eviscerations were required.2 Another group described a patient who had PPV within 8 hours of the onset of EKPE symptoms; VA had improved from 6/120 to 6/6 at the 12-month follow-up.9 These results support the role of early PPV in the management of EKPE.

A series of five patients had previously been treated for EKPE at the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital. All were treated with intravenous and intravitreal antibiotics. Four of the five patients required enucleation or evisceration, and the fifth became phthisical. Our patient, the sixth case, presented early in the course of disease, and was treated with systemic and intravitreal antibiotics, as well as with early PPV. In contrast to the preceding cases, the visual outcome was excellent.

The incidence of K. pneumoniae liver abscess in the Asia-Pacific region is increasing. Early ophthalmology referral for patients with suspected or proven K. pneumoniae liver abscess is recommended. In patients with known EKPE, early PPV should be performed in conjunction with intensive systemic and repeated intravitreal antibiotic and steroid therapy to reduce intraocular bacterial and inflammatory load, and to aid the penetration of intravitreal antibiotics to the subretinal focus of infection. This may increase the chances for rescuing the eye and improving the visual outcome.

Lessons from practice

-

Endogenous Klebsiella pneumoniae endophthalmitis (EKPE) carries an extremely poor visual prognosis.

-

In patients admitted to general hospitals with K. pneumoniae liver abscess, a high index of suspicion of EKPE is recommended, and early referral to ophthalmology services advised.

-

Early surgical intervention in EKPE can salvage vision in this otherwise devastatingly blinding disease.

Figure

A, B: Intraoperative photographs of the posterior segment of the eye, showing retinal detachment with a subretinal abscess in the right eye (A) and a subretinal abscess in the left eye (B); the white arrows indicate the optic nerves. C: Computed tomography (CT) image of the orbits at presentation, showing left-sided proptosis with associated inflammation of the sclera (white arrow) and periorbital soft tissues. D: Abdominal CT scan, showing a 5.0 × 5.7 cm abscess (white arrow) in segments V/VIII of the liver. E, F: Slit lamp photos of the right (E) and left (F) eyes 13 days after initial presentation.

more_vert

more_vert