We describe a rare case of domestically acquired hepatitis E in Australia and the first in an Australian liver transplant recipient. The infection was successfully treated with ribavirin.

Clinical record

A 48-year-old Australian man of European ancestry received his third liver transplant in February 2013 for hepatic failure precipitated by ischaemic cholangiopathy and secondary biliary cirrhosis. His first liver transplant was performed 10 years earlier for complications of cirrhosis arising from autoimmune hepatitis – primary sclerosing cholangitis overlap syndrome, but required retransplantation after 3 months due to hepatic vein thrombosis and hepatic infarction. The second liver transplant was complicated by hepatic artery thrombosis, resulting in ischaemic cholangiopathy.

For his third transplant, from 13 days before to 13 days after transplantation, the patient received blood products from 22 individual donors. His initial immunosuppressive regimen comprised cyclosporin 150 mg twice daily, prednisolone 20 mg once daily and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) 500 mg twice daily. Subsequently, moderate renal impairment (creatinine, 170 µmol/L; reference interval [RI], 60–110 µmol/L) and cytopaenias prompted gradual cyclosporin and MMF dose reductions. Blood products were not required, and results of liver function tests (LFTs) remained normal.

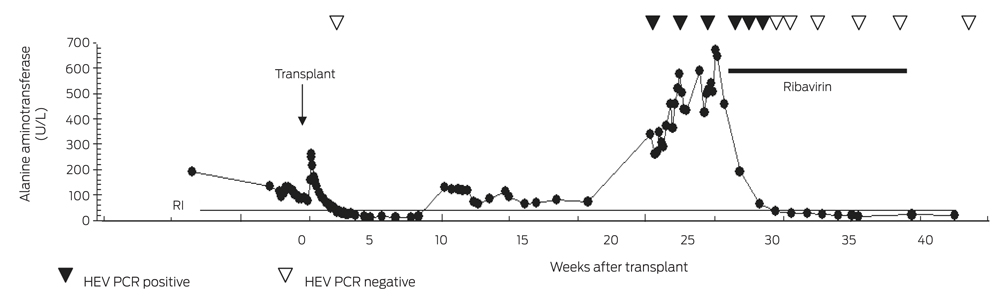

Ten weeks after transplantation, an elevation in LFT levels occurred (alanine aminotransferase [ALT], 131 U/L [RI, < 40 U/L]; aspartate aminotransferase [AST], 53 U/L [RI, < 45 U/L]; γ-glutamyltransferase [GGT], 76 U/L [RI, < 60 U/L]). Abdominal ultrasound was unremarkable, and the raised LFT results gradually settled without adjustment of the immunosuppressive regimen.

Twenty-two weeks after the patient’s transplantation, he developed significant transaminitis (ALT, 338 U/L; AST, 215 U/L; GGT, 183 U/L; alkaline phosphatase, 126 U/L [RI, 35–135 U/L]; total bilirubin, 13 µmol/L [RI, < 20 µmol/L]) (Box 1).

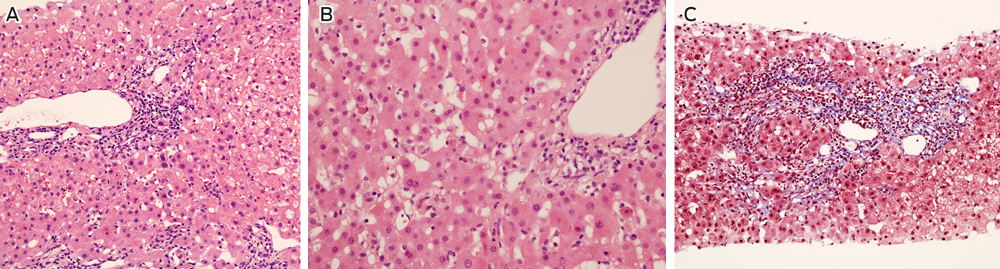

The patient adhered to his immunosuppressive regimen and had not commenced other medications. Physical examination was unremarkable and abdominal ultrasound did not show biliary or hepatic vascular abnormalities. A liver biopsy was performed and reported as consistent with moderately active acute rejection. This prompted methylprednisolone therapy (500 mg once daily for 3 days) followed by prednisolone (50 mg once daily) and replacement of cyclosporin with tacrolimus (3 mg twice daily). MMF was continued unchanged. A second liver biopsy was performed 1 week later due to a further rise in the ALT level (456 U/L), which demonstrated non-specific hepatitis without definite features of rejection or an autoimmune aetiology (Box 2). Subsequent comparison of these biopsies by a specialist histopathologist confirmed acute hepatitis in both samples, without significant features of rejection on either biopsy.

Investigation for infectious causes excluded hepatitis A, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and human herpesvirus 6. Anti-hepatitis E IgG antibody (HEV ELISA, MP Biomedicals Asia Pacific) was not detected, but an in-house hepatitis E virus (HEV) reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay (Appendix) detected HEV RNA in the patient’s blood. HEV RNA was also detected at the Victorian Infectious Diseases Reference Laboratory (VIDRL), and nucleotide sequencing demonstrated genotype 3 HEV. Paraffin-embedded liver tissue from the biopsy collected 22 weeks after transplantation was HEV RNA positive, as were blood samples collected 22 and 23 weeks after transplantation. Retrospective testing of the patient’s and liver donor’s blood at the time of transplantation was negative for anti-HEV IgG antibody and HEV RNA. A biopsy of the donor liver, collected at the time of transplantation, was also HEV RNA negative.

Stored blood from all donors of the blood products were tested for anti-HEV IgG antibody by two assays (HEV IgG ELISA, Genelabs Diagnostics; HEV-IgG ELISA, Beijing Wantai), anti-HEV IgM antibody (HEV-IgM ELISA, Beijing Wantai) and by in-house (VIDRL) and commercial (RealStar HEV RT-PCR 1.0, Altona Diagnostics) HEV RT-PCR. All 22 donors’ samples were negative for anti-HEV IgM antibody and HEV RT-PCR. Three donors were found to have detectable anti-HEV IgG antibody levels. Two of these donors were found to have detectable IgG anti-HEV antibody levels in both assays; one was born in South Africa but had not left Australia in 6 years, and the second had travelled frequently to India in the past 5 years, most recently 8 months before donation. The third donor had never travelled outside of Australia, but had worked in a piggery. Repeat samples collected 9 months after donation from these donors and 18 of the 19 seronegative donors produced the same serological results.

The patient was born in Australia, had not recently travelled overseas, and worked in a city office. He had no contact with overseas travellers, and had not visited rural areas, farms or had any livestock exposure. He consumed pork regularly, which was sourced from local supermarkets.

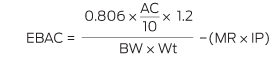

Despite reducing the patient’s immunosuppression, the hepatitis continued to worsen over the next 5 weeks (ALT, 669 U/L) and HEV RNA remained detectable (Box 1). Ribavirin at a dose adjusted for his renal impairment (200 mg once daily) was commenced with an immediate improvement of his liver function. HEV RNA was last detected 17 days after commencement, and HEV RT-PCR was negative after 24 days. Pegylated interferon alfa was not used due to pre-existing cytopaenia and the risk of precipitating acute rejection. The patient received a 12-week course of ribavirin and remained HEV RNA negative 15 weeks after cessation. The patient had not developed anti-HEV IgG antibody 7 months after onset of hepatitis.

Discussion

HEV is a non-enveloped RNA virus identified in 1980 as the cause of “epidemic, non-A, non-B hepatitis”, a waterborne illness similar to hepatitis A.1 After an incubation period of 2–9 weeks2 the illness is usually self-limiting, but can progress to severe disease, particularly during advanced pregnancy, and among very young children and those with pre-existing chronic liver disease.3

There are four human HEV genotypes. Genotypes 1 and 2 cause large outbreaks in Asia, Africa and Central America via contaminated water. Genotypes 3 and 4 are predominantly swine viruses causing sporadic zoonotic disease in Europe, the United States and Eastern Asia.4

Acute hepatitis E is most reliably diagnosed either serologically by IgG anti-HEV antibody seroconversion,1,3 or by detection of HEV RNA in blood or faeces. HEV RNA is detectable in blood samples from up to 2 weeks before and 1 week after the onset of jaundice, and in stool it is detectable for up to 3 weeks after the onset of jaundice.

In developed countries, genotype 3 HEV is mostly transmitted by the consumption of undercooked pork or raw offal,3 and occasionally from animal contact or blood transfusion.1,4 The seroprevalence in Europe and the US is lower than for hepatitis A, but higher than for hepatitis B and hepatitis C.1,3 However, the incidence of acute hepatitis E in developed countries is unknown, with only five US cases of domestically acquired acute hepatitis E reported from 1997 to 2006.3

The source for HEV infection in our patient was unknown, but the donor liver, blood products, or contaminated food or water could have been responsible. Solid organ donors are not routinely screened for HEV infection in Australia, although this is recommended where HEV is endemic.4 Donor liver transmission of HEV, presenting 5 months after transplantation from an anti-HEV antibody negative but HEV RNA positive donor has occurred,5 but in our case both donor blood and liver tested negative for anti-HEV IgG antibody and HEV RNA. The blood donor who had travelled to India is a possible source as this donor’s anti-HEV IgG antibody sample-to-cut-off ratio was high in both IgG assays, which has been correlated with a recent illness compatible with hepatitis E and overseas travel.2 A contaminated food source cannot be excluded, as anti-HEV seropositive pigs have been found in Australian piggeries6 and, although processed, up to 80% of the ham, bacon and smallgoods sold in Australia is made from imported pig meat, mostly from the US, Canada and the European Union.7

Chronic hepatitis E can develop in solid organ transplant recipients, patients receiving cancer chemotherapy, and people with HIV. About two-thirds of solid organ transplant recipients infected with HEV develop chronic disease,8 which can be severe and cause significant inflammation and fibrosis.1 In our patient, the undetectable anti-HEV IgG antibody is likely a reflection of his immunosuppression.9

Management options for hepatitis E in solid organ transplant recipients include reducing immune suppression, pegylated interferon alfa or ribavirin therapy, or a combination of these. Reduction of immunosuppression alone can clear HEV in a minority of solid organ transplant recipients and pegylated interferon alfa has been used effectively to treat chronic hepatitis E after transplantation, but may precipitate donor organ rejection.4,8 Although not approved for this use in Australia, ribavirin for at least 3 months has been shown to produce sustained virological responses in at least two-thirds of patients with chronic hepatitis E,8 and is recommended as first-line treatment in solid organ transplant recipients who do not clear the virus despite reducing the immunosuppression.4

Domestically acquired hepatitis E has been reported rarely in Australia since the mid 1990s.10–12 To our knowledge, this is the first case of an Australian organ transplant recipient with hepatitis E successfully managed with antiviral therapy. Domestically acquired cases in Australia may be missed due to infrequent HEV serological testing in the absence of a travel history and the relative unavailability of HEV RNA testing. Hepatitis E should be considered in patients with unexplained hepatitis, and solid organ transplant recipients or those with compromised immune systems with hepatitis should be tested for HEV RNA because anti-HEV antibody tests may be negative in these patients.

1 Timeline of laboratory test results and treatment

2 Liver biopsy findings 5 months after transplant

more_vert

more_vert