Enterovirus infections, although commonly asymptomatic, may also be associated with a wide range of clinical diseases including hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD), herpangina, aseptic meningitis and acute flaccid paralysis.1 Transmission of enteroviruses can occur directly by the faecal–oral route, from contaminated environmental sources, or by respiratory droplet transmission.1

Human enterovirus 71 (EV71) is a major cause of HFMD worldwide and, in the past 15 years, has caused large outbreaks in South-East Asia associated with severe neurological disease and deaths.2 Patients with severe and fatal cases of EV71 infection have usually been diagnosed with meningitis, encephalomyelitis or brainstem encephalitis associated with systemic features such as cardiopulmonary compromise and myocarditis.3,4 Large outbreaks of EV71 infection have been reported in Victoria (1986), Perth (1999) and Sydney (2000–2001), and all outbreaks included cases of patients with severe neurological disease.5–7 Enterovirus infections (apart from poliomyelitis) are not notifiable in New South Wales.

In early March 2013, paediatricians practising in the northern beaches area of Sydney alerted their public health unit (PHU) to an increase in the number of young children presenting with severe neurological manifestations of enterovirus infection. The Sydney Children’s Hospital in the Sydney suburb of Randwick confirmed EV71 infection in two of these cases and suspected infection in others. The PHU interviewed parents of 16 children with suspected cases, but identified no point sources of infection. The PHU issued alerts to clinicians and the local community, and the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network circulated advice to clinical staff on diagnosing and managing patients with suspected neurological complications of enterovirus infection.

Also in March 2013, New South Wales Health issued a statewide media release and alerts to general practitioners, emergency departments (EDs), paediatricians and neurologists, and established an enhanced surveillance system focusing on children with severe enterovirus infection. The aims of this surveillance were to describe the extent of the outbreak and the clinical features of cases to aid in their identification and management. Here, we report on the findings of this surveillance.

Methods

The enhanced enterovirus surveillance system had two arms. The first used the existing NSW Public Health Real-time Emergency Department Surveillance System (PHREDSS) to monitor ED presentations and admissions from 14 April to 2 June 2013 of children aged less than 10 years with a provisional diagnosis of HFMD or “meningitis or encephalitis”. The resulting data were compared with historical data retrospectively available from PHREDSS, which collects information on all visits to 59 NSW EDs, and includes about 84% of ED activity in the state.8

The second arm was enhanced surveillance established at the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network (Sydney Children’s Hospital at Randwick and The Children’s Hospital at Westmead). Cases were defined as children aged under 10 years admitted from 1 January to 2 June 2013 with suspected or confirmed enterovirus infections and with neurological diagnoses (meningitis, encephalitis, meningoencephalitis, acute flaccid paralysis or transverse myelitis).

Cases of suspected EV71 infection for the period 1 January to 13 April 2013 were identified retrospectively through review of daily hospital admission lists. Only demographic and laboratory testing data were collected for these patients.

From 14 April to 2 June 2013, hospital admission lists were reviewed daily by designated clinical staff. Clinical features, treatment and final diagnosis were gathered for all suspected cases of EV71 infection. Respiratory, stool and/or cerebrospinal fluid samples were tested for enterovirus with standard nucleic acid test kits. A subset of samples that tested positive were referred to either of the two state enterovirus reference laboratories for EV71 typing. Both suspected and confirmed cases were included in the analysis. Presence of the virus in samples from non-sterile sites might indicate coincidental carriage, but in samples from sterile sites, the viral load is often low.9–11

Results

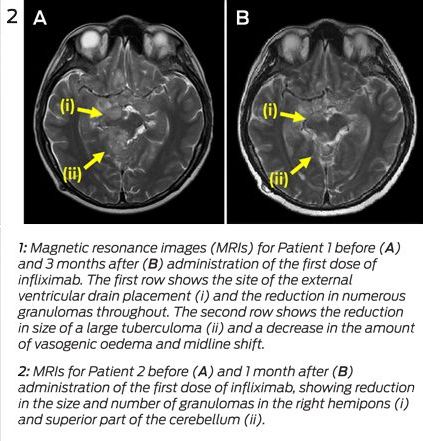

Presentations to EDs for HFMD in children aged under 10 years began to rise in February 2013, peaked in late March, then remained above the usual range through to June (Box 1, A). This was temporally associated with a sharp rise in the number of children with HFMD who required hospital admission (Box 1, B). Presentations to EDs for HFMD also rose in the final quarter of 2011, but without an increase in resulting admissions, indicating that the outbreak of 2013 may have been associated with more severe illness.

The number of ED presentations of children with “meningitis and encephalitis” began to increase in mid November 2012 and remained above the usual range until June 2013 (Box 1, C). Most of these children were admitted, consistent with historical trends (Box 1, D).

Between 1 January and 2 June 2013, 119 cases of suspected EV71 infection were identified in the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network. Suspected cases were evenly distributed between the two hospitals (53% at Sydney Children’s Hospital at Randwick and 47% at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead). The median age of infected children was 19 months (range, 1 month to 10 years) and 47% were female.

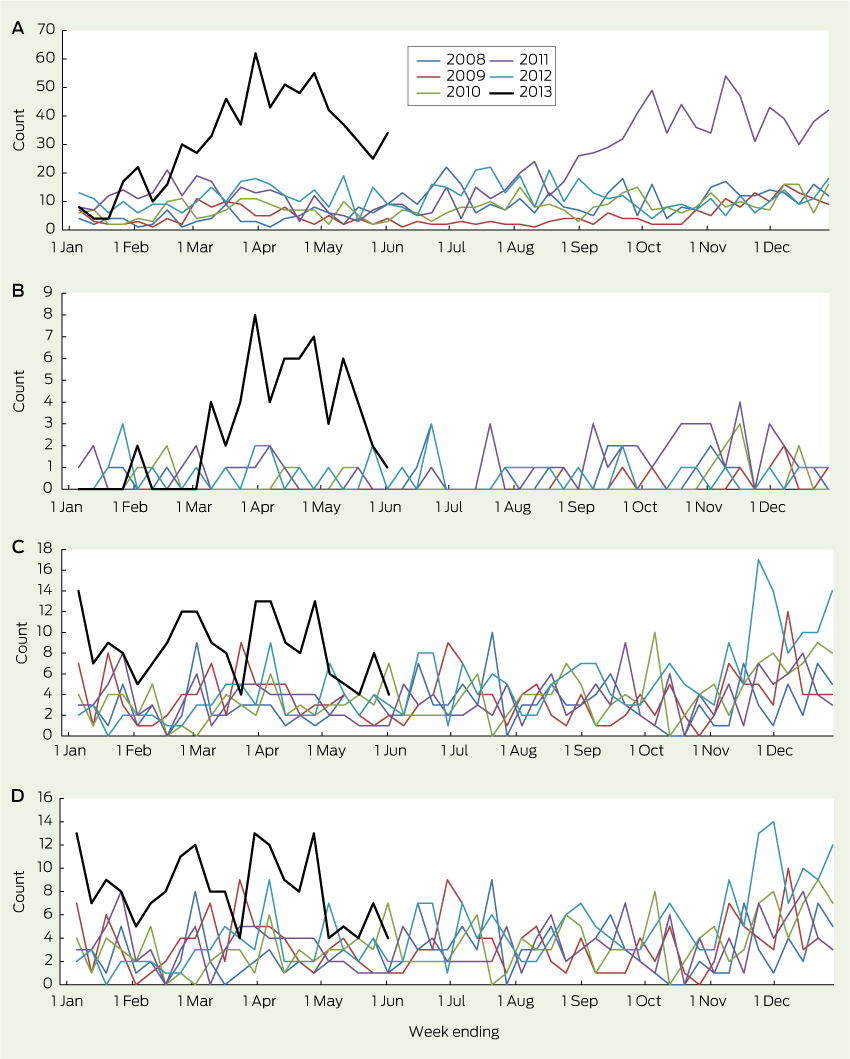

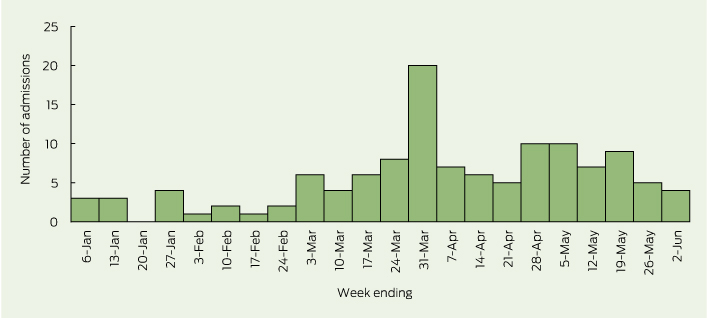

The weekly number of suspected cases rose sharply at the beginning of March 2013, and peaked at 20 cases in the final week of that month (Box 2). A second, smaller rise was noted in late April and May 2013.

Although cases of suspected EV71 infection were widely spread within the Sydney metropolitan area, Sydney’s northern beaches, central parts of Western Sydney and the eastern suburbs experienced more intense activity. Most suspected cases in the March 2013 peak came from the coastal areas of Sydney, particularly the northern beaches and eastern suburbs. During April and May, the number of suspected cases coming from the eastern suburbs remained stable, while the numbers from western Sydney increased and from Sydney’s northern beaches declined sharply.

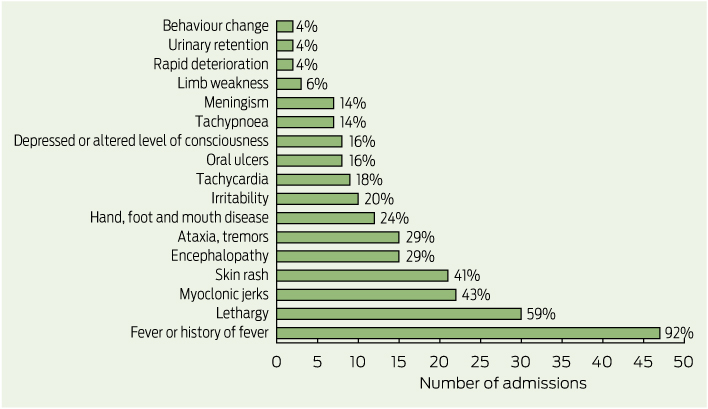

Case forms were completed for all 50 children with suspected EV71 infection who presented between 14 April and 2 June 2013. The most common presenting clinical features were fever (47 children), lethargy (30 children), myoclonic jerks (22 children) and skin rash (21 children) (Box 3). Only 12 children (24%) presented with signs or symptoms of HFMD. The average length of hospital stay was 4.2 days. Five of the 50 children were admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) and three of these required intubation. The average length of stay in the ICU was 2.4 days. Two children with suspected EV71 infection were treated with intravenous immunoglobulin and six received corticosteroids. The most common diagnoses at discharge were meningitis (15 children), encephalomyelitis (10 children), myoclonus (seven children) and viral meningitis (six children).

Of the 50 children with suspected EV71 infections and completed case forms, 45 tested positive for enterovirus. Infections were typed for 37 of these, and 18 cases were confirmed to be EV71. Other enteroviruses identified included coxsackieviruses (11 children) and echoviruses (four children). Two children had both EV71 and a coxsackievirus, and two had both coxsackieviruses and echoviruses.

Discussion

EV71 emerged as an important cause of severe neurological disease in young Sydney children during the first half of 2013. Activity peaked in March 2013. The focus of the outbreak moved from Sydney’s northern beaches area to its eastern and western suburbs over several weeks. Myoclonic jerks were a relatively common feature of severe infection.

A number of countries in Asia have implemented HFMD surveillance programs in the past 15 years.2,12 HFMD and enterovirus infection are not notifiable diseases in NSW, as most infections are asymptomatic or mild, and many patients are unlikely to see a doctor. This means that notification does not provide a mechanism for developing meaningful patient-based interventions to interrupt transmission. Population-based disease-control measures focus instead on personal hygiene and sanitation. The effect of social-distancing measures, including the closure of childcare facilities,13 has been questioned given the limited evidence for its efficacy, the unquantified but likely substantial socioeconomic costs, and the risk of prolonging the epidemic.1

Two previous studies have suggested that EV71 epidemic activity has followed the introduction of circulating genotypes from Asia into Australia.14,15 EV71 was detected in samples from five patients with acute flaccid paralysis and other patients with suspected enterovirus infections in early 2013, and phylogenetic analysis showed homology with the EV71 C4a subgenogroup circulating in Asia, which was associated with severe neurological complications.16

Our report has important limitations. First, the use of syndromic ED surveillance has uncertain sensitivity and specificity for enterovirus infections. The positive predictive value of syndromic diagnoses would, however, be expected to rise during recognised outbreaks. Second, enhanced surveillance focused on two sentinel children’s hospitals. Other infected patients are likely to have presented to other hospitals in and outside Sydney. Third, before enhanced surveillance, further typing of samples testing positive for enterovirus was not routine practice, so many samples collected between 1 January and 14 April were not typed. Fourth, our description of suspected cases included some patients who were not confirmed to have EV71 infection, so may not truly represent the severe outcomes of the infection.

The continued escalation of EV71 epidemics in Asia, and evidence of the introduction of the EV71 strain into Australia from Asia suggest that enterovirus may continue to be a public health problem here. The results of a Phase III clinical trial of a vaccine were recently published,17 but vaccines have limitations.18 Other vaccines are being developed, and perhaps EV71 will become vaccine-preventable. The use of routinely collected ED data appears to be a useful and efficient method for monitoring enterovirus infections, including the more severe outcomes associated with EV71 epidemics.8

1 Total weekly counts of emergency department presentations (A) and admissions (B) for hand, foot and mouth disease, and emergency department presentations (C) and admissions (D) for “meningitis or encephalitis” for children aged less than 10 years at 59 New South Wales hospitals — 2013 up to 2 June (black line) compared with each of the 5 previous years

2 Weekly number of children aged less than 10 years admitted to the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network between 1 January and 2 June 2013 with clinical features of meningitis, encephalitis, meningoencephalitis, acute flaccid paralysis or transverse myelitis and suspected or confirmed enterovirus infection

3 Reported presenting clinical features for suspected or confirmed cases of enterovirus 71 infection in children aged less than 10 years admitted to the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network, 14 April to 2 June, 2013

more_vert

more_vert