Lyme borreliosis is a tick-borne zoonosis endemic in many parts of the world. We report the first case of Lyme neuroborreliosis in an Australian traveller returning from an endemic area. The diagnosis should be considered in patients with chronic meningoencephalitis and a history of travel to an endemic area.

Clinical record

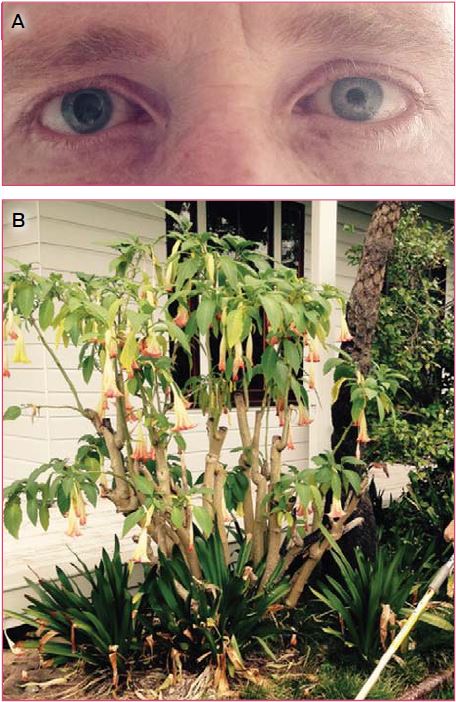

A 58-year-old woman of European ancestry presented to a rural hospital in New South Wales in May 2014 with an 8-month history of worsening motor instability, confusion and bilateral occipital headaches associated with photophobia, lethargy and somnolence. The patient was from Geraldton in Western Australia and was staying for 2 weeks with her family in NSW. Her symptoms had started 1 month after returning from Lithuania, where she had spent 3 weeks. A tick had bitten her in the pubic hairline during a trip to a pine forest 30 km from Vilnius. One month later, the patient developed two circular non-pruritic rashes on her right thigh (distal to the site of the tick bite) and lower leg, each about 30 mm in diameter; they resolved after 2 weeks without specific intervention. She had experienced continuing headaches, lethargy and a self-limiting episode of diplopia that prompted her to see her general practitioner. Computerised tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of the brain performed before she presented to the hospital showed nothing abnormal.

The patient’s past medical history included hypertension that was well controlled with irbesartan. On presentation, she was afebrile. There were no focal neurological signs or papilloedema. Cardiovascular, respiratory and gastrointestinal parameters were within normal limits. There were no rashes on her extremities, nor evidence of synovitis in her joints.

The results of a full blood examination, urea and electrolyte assessments and liver function tests were within normal limits. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) white cell count was 377 × 106/L (reference interval [RI], 0–5 × 106/L), consisting purely of monocytes (ie, no polymorphonuclear leukocytes). No organisms were identified by Gram staining; the results of acid-fast bacilli staining were also negative. CSF biochemical parameters were markedly abnormal, with elevated protein levels (1.93 g/L; RI, 0.15–0.45 g/L) and reduced glucose levels (1.3 mmol/L; RI, 2.8–4.4 mmol/L). Cryptococcal antigen was not detected by lateral flow assay, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis was negative for herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2, enterovirus, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antibody to syphilis treponema and to HIV was not detected.

Given the clinical presentation and the history of travel to an area where Lyme disease is endemic, serological testing for Borrelia in both serum and CSF was requested, and treatment with ceftriaxone (4 g daily) was commenced, with a presumptive diagnosis of Lyme neuroborreliosis.

Serological screening was performed at the Institute of Clinical Pathology and Medical Research, Westmead (Sydney), with an enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for IgG against recombinant antigens from Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto strain B31, B. afzelii and B. garinii (NovaLisa Borrelia burgdorferi IgG, NovaTec Immundiagnostica GmbH, Germany). The signal to cut-off ratio in this assay was 6.83 for serum and 5.57 for CSF (ratios less than 0.9 are considered negative).

To confirm these results, western immunoblotting was undertaken using a modification of the polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) method described by Dressler and colleagues.1 Sonicated B. burgdorferi strain 297 (at 0.5 mg/mL) and B. afzelli ATCC 51567 (at 1.0 mg/mL) were separately applied to precast SDS-PAGE gels (ExcelGel SDS Homogeneous 12.5, GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Sweden). The serum of our patient showed IgG responses to two B. burgdorferi antigens (molecular weights: 41, 58 kDa) and five B. afzelii antigens (22, 39, 41, 58, 83 kDa). IgG to the same antigens, as well as to a sixth B. afzelii antigen (45 kDa), was detected in her CSF. The criteria of the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) stipulate that five or more specific IgG bands are required for a positive serological result.2

The patient returned to Geraldton, where she completed two weeks of treatment with intravenous ceftriaxone (4 g daily). The cellular and biochemical parameters of CSF collected 3 weeks after completion of treatment had improved: the white cell count was 45 × 106/L, the protein levels were 0.7 g/L and the glucose concentration was 2.3 mmol/L. Five months later, her CSF parameters were completely normal, with a normal biochemical profile and no pleocytosis. The patient continues to see her GP and has made a good clinical recovery; her headaches, lethargy and neurological symptoms have all resolved.

Discussion

Our case highlights the importance of obtaining a thorough travel history in a patient presenting with chronic meningoencephalitis. Our review of the literature indicated that this was the first case of Lyme neuroborreliosis imported into Australia from overseas. Clinicians should consider neuroborreliosis in patients with a history of travel to an endemic area who present with persistent neurological symptoms. Other causes of chronic meningitis include cryptococcal meningitis, which is endemic in Australia, but had been excluded in our patient. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection and tick-borne encephalitis are further diagnoses to consider in travellers with meningoencephalitis who have returned from Eastern Europe.

Lyme disease is a multisystem infectious disorder transmitted by ticks of the Ixodes complex.3 Three B. burgdorferi sensu lato species, namely B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. garinii, and B. afzelii, are pathogenic to humans in Europe. In contrast, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto is the only species known to cause human infection in the United States.3 The disease has protean manifestations, depending on the clinical stage at presentation. Stage I disease usually presents with a typical rash, erythema migrans, 7–14 mm from the site of the tick bite. Constitutional symptoms, including headache, myalgia, arthralgia and fever, may accompany the erythema migrans. Stage II disease is characterised by dissemination to other skin areas, the nervous system, joints or heart, and may include a wide variety of symptoms. Stage III, or late Lyme disease, occurs months to years after a tick bite, and usually causes large joint arthritis or neurological symptoms.3 In our patient, the presence of an erythema migrans rash at more than one site, presented together with neurological symptoms, indicated stage II disease.

Two-tier serological assessment — a screening EIA followed by confirmatory immunoblotting — remains the mainstay of diagnosis for Lyme borreliosis, although molecular methods and culturing clinical specimens are also possible.2The diagnostic sensitivity of culturing Borrelia species is poor, so that it is rarely undertaken in clinical practice, its use being largely limited to research settings.4 Molecular methods have a higher diagnostic sensitivity when using skin biopsies from an erythema migrans or synovial fluid than when testing blood or CSF.4,5 Molecular methods have not been standardised across laboratories and false-positive results are possible.4

On the other hand, the recombinant EIA for anti-Borrelia IgG has high sensitivity and specificity after the first few weeks of infection. The results of testing the serum and CSF of our patient for anti-Borrelia IgG were highly positive. Confirmation by immunoblotting greatly increases the positive predictive value of EIA, but this technique may be less sensitive, although it is very specific when using the CDC criteria for IgG immunoblotting in Lyme disease. In our case, only the IgG blotting results for B. afzelii antigens met the CDC criteria for a positive finding.

The European Federation of Neurological Sciences guidelines require two of the following criteria to be fulfilled for a possible diagnosis of Lyme neuroborreliosis, and that all three be met for a definite diagnosis:

- neurological symptoms;

- CSF pleocytosis; and

- detection of intrathecal antibodies or, if symptoms began in the past 6 weeks, identification of the pathogen in the CSF by PCR or culture.6

Our patient met all three criteria, making this a definite diagnosis of Lyme neuroborreliosis.

The clinical presentation of Lyme neuroborreliosis differs according to the Borrelia species involved. B. garinii is the most common cause of Lyme neuroborreliosis in Europe, followed by B. afzelii. B. garinii infection often manifests as typical early neuroborreliosis, characterised by painful meningoradiculitis (Bannwarth syndrome) and meningeal irritation, whereas the clinical features of central nervous involvement in B. afzelii infection, as in our patient, are often non-specific and difficult to diagnose.5 In contrast to infection with B. garinii, CSF parameters in patients with Lyme neuroborreliosis caused by B. afzelii can be atypical, with a normal biochemical profile and without pleocytosis.5 In our patient, the presence of persistent non-specific neurological and constitutional symptoms, together with positive CSF and serum IgG immunoreactivity to B. afzelii antigens, provided enough evidence to attribute this infection to B. afzelii.

Oral administration of amoxicillin or doxycycline is usually the treatment of choice for early stage Lyme borreliosis. Patients with neurological or cardiac manifestations are typically treated for 2–4 weeks with intravenous ceftriaxone.3 Longer-term parenteral treatment is not recommended, because it does not provide any additional improvement in patients with persisting neurological or constitutional symptoms; it is also associated with adverse events.7 Improvement in both clinical and CSF markers after 2 weeks of intravenous ceftriaxone in our patient was reassuring, and suggests that a shorter duration of treatment is possible even in patients with neurological symptoms.

The existence of Lyme disease in Australia has been debated for decades,8 and in recent years there has been growing public interest. In February 2014, the Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia released a position statement on diagnostic laboratory testing for Lyme disease in Australia and New Zealand.9 Ticks of the genus Ixodes are present in Australia, but species known to transmit Borrelia species have not been found.10Earlier research,10 as well as the most recent study of ticks in areas around the northern beaches of Sydney and other parts of Australia (Associate Professor Peter Irwin, Murdoch University, WA, personal communication, November 2014) have not found Borrelia species in Australian ticks.

Lyme disease can present as non-specific symptoms that persist for weeks to months after infection. A careful travel history is therefore an important part of the assessment of any patient with clinical features suggesting the disease.

more_vert

more_vert