Clinical record

Two patients with ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency, a urea cycle disorder, were transferred to our intensive care unit within 12 months. Both were previously healthy men who initially presented with nondescript but progressive neurological symptoms after minor procedures (case summaries in Box 1).

Each patient developed their initial neurological symptoms (headache, mental slowness, incoordination) about 24–48 hours after the likely precipitant, which in each case was a single dose of a corticosteroid. In Patient 1, sleepiness at 48 hours progressed to incoherence, blurred vision, and severe agitation that required intubation 2 days later. In Patient 2, headache, nausea, blurred vision and epigastric pain at 48 hours progressed over the following 2 days to confusion and slow speech; by the following day, coma had developed, requiring intubation.

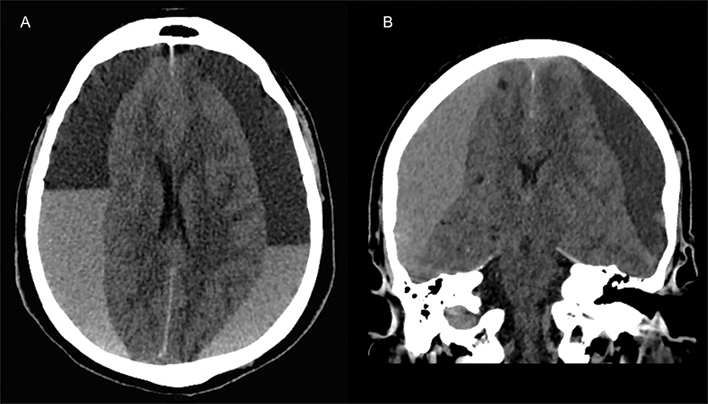

On their presentation to a peripheral hospital, an extensive panel of pathology investigations had been undertaken for each patient, including blood tests (full blood count, renal function tests, liver enzyme levels, coagulation profile and inflammatory markers), lumbar puncture and brain imaging (computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging). The results of these investigations were all unremarkable.

Identification of significant hyperammonaemia was delayed until about 36–48 hours after presentation to hospital. The patients were comatose when transferred to our hospital. Patient 1 had a prolonged stay in our intensive care unit, with a persistent minimally conscious state; Patient 2 proceeded to brain death and organ donation.

Physicians will be familiar with the most common causes of hyperammonaemia, including an increased protein load associated with liver disease, and urea cycle enzyme dysfunction caused by medications such as sodium valproate. Less common but important causes of elevated blood ammonia levels are the inherited urea cycle disorders (UCDs). The most severe forms present in early life, but milder forms of these disorders may become evident during adulthood.

UCDs are a group of inborn errors of metabolism, with an estimated total incidence of between 1:80001 and 1:30 0002 births. They are caused by dysfunction of any of the six enzymes or two transport proteins involved in urea biosynthesis, a process that predominantly occurs in the liver. The urea cycle is the terminal pathway for the disposal of ammonia formed during amino acid catabolism. Ammonia is neurotoxic, and any acute rise in blood levels beyond 50 μmol/L may cause neurological symptoms. While ammonia levels above 100 μmol/L may cause obtundation, milder elevations should be interpreted within the clinical context of their occurrence.

The UCD affecting our two patients was ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiency, the most common of the urea cycle disorders. OTC deficiency is an X-linked trait, and is therefore more commonly expressed in males, although female carriers may decompensate after a significant stress, such as childbirth.3 The other UCDs are autosomal recessive traits.4

First presentation in adulthood can be attributed to the milder degree of the deficiency, and frequently also to self-limitation of protein intake as a learned behaviour, permitting stability until an environmental stressor supervenes. Conditions that lead to increased demands upon the urea cycle, such as protein load, infection, systemic corticosteroids, rapid weight loss, surgery, trauma and chemotherapy,5 can all precipitate decompensation in individuals with a UCD. The case of a 44-year-old man who died of a previously undiagnosed OTC deficiency after coronary artery bypass surgery was reported in this Journal in 2007.6

In the two patients described in our article, a single but significant incidental dose of corticosteroid was the initial precipitating event, with prolonged fasting perpetuating a vicious metabolic cycle that culminated in severe hyperammonaemia.

Hyperammonaemia in adults may present with psychiatric or neurological symptoms, including headache, confusion, agitation with combative behaviour, dysarthria, ataxia, hallucinations and visual impairment,3 symptoms that reflect toxic metabolic encephalopathy. Abdominal symptoms (nausea, vomiting) may accompany the nervous system phenomena.

Our two cases illustrate the course of progressive hyperammonaemia if treatment is not initiated early: worsening cognitive impairment and cerebral oedema, with the development of coma, seizures and death due to intracranial hypertension.

When there is no alternative explanation for the disproportionate and progressive nature of a patient’s cognitive disturbance, this should be taken as an important cue for exploring the possibility of a metabolic aetiology. As the decline occurs over a period of days, there is a window for life-saving intervention if the condition is recognised in time.

Measurement of the blood ammonia level as part of a metabolic screen should be performed at the earliest possible opportunity in such a case. If the ammonia level is elevated, a metabolic specialist should be consulted, a plasma amino acid profile prepared, urinary organic acids and orotic acid measured, and emergency treatment for hyperammonaemia initiated.

The three elements of treatment of a urea cycle-linked hyperammonaemic coma include:

-

physical removal of ammonia by haemodialysis or haemodiafiltration;

-

reversal of the catabolic state by insulin/dextrose and intralipid infusion; and

-

temporarily withholding protein and commencing nitrogen scavengers, once available.

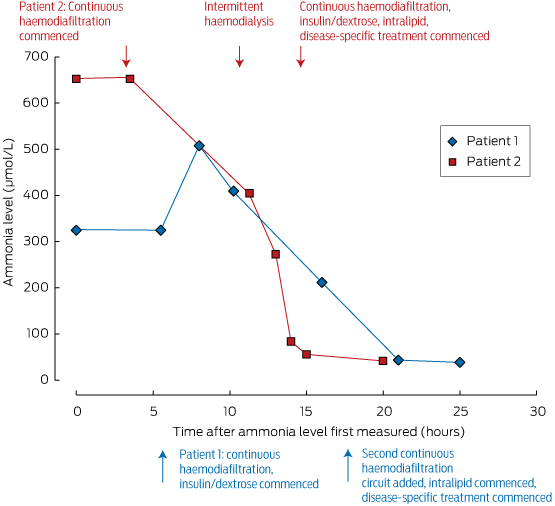

These measures should be initiated under the guidance of a metabolic physician, and in an intensive care unit where agitation or coma can be managed. Ammonia levels can be rapidly reduced by dialysis; its removal is dependent on flow rates, making intermittent haemodialysis the most effective method of clearance, as shown in Box 2. For this reason, we advocate intermittent dialysis rather than continuous venovenous haemodiafiltration for early ammonia control in the emergency setting.

While severe neurological impairment at the start of treatment is of great concern, this should not in itself be a reason to withhold treatment, as good neurological recovery is possible. This is illustrated by the case report of a middle-aged patient who recovered, despite decorticate posturing when therapy was initiated.5

We advocate early assessment of ammonia levels in patients with an unexplained altered conscious state, or when their cognitive disturbance seems disproportionate to any concurrent systemic illness. Many of the necessary elements of care can be initiated in non-tertiary intensive care units. Initiation of treatment at the hospital of presentation is essential, as this is a medical emergency; neurological outcome and survival are critically dependent on the timing of intervention. If recognised early and treated appropriately, the prognosis for neurological recovery is good.

Lessons for practice

-

Urea cycle disorders may first present in adulthood, unmasked by triggers such as systemic illness, increased protein load, surgery or corticosteroids.

-

Assessing ammonia levels is a simple but critical test in patients with unexplained impaired consciousness.

-

A session of intermittent haemodialysis is highly effective for rapid ammonia control, and superior to continuous haemodiafiltration for rapid correction.

-

Emergency treatment of hyperammonaemia should be undertaken early to prevent devastating neurological injury.

Box 1 –

Case histories of the two patients

|

|

Patient 1: 24 years old, male

|

|

Medical history

|

|

- Obstructive sleep apnoea; no notable family history; high-functioning individual

- Likely precipitant: intraoperative dexamethasone (8 mg) during nasal septoplasty

|

|

Progress

|

|

- Vagueness and lethargy 48 h after operation, progressing over 24 h to incoherence

- Intubated 12 h later for severe agitation

- GCS declined to 5–6 over next 48 h; ammonia level, 334 μmol/L (RR, < 50 μmol/L); disease-specific treatment started

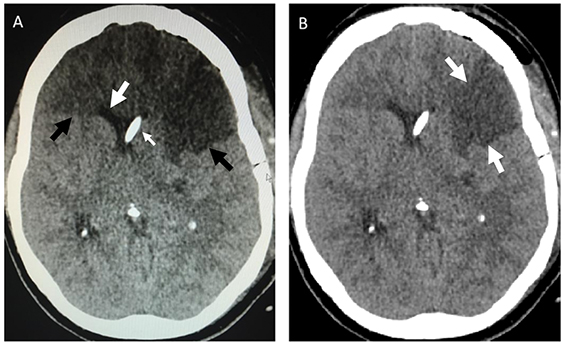

- Raised intracranial pressures 6 h later (dilated pupils with cerebral oedema on CT brain), leading to decompressive craniectomy complicated by frontal haematoma, requiring evacuation

- Prolonged intensive care unit and hospital stay

|

|

Outcome

|

|

- Persistent minimally conscious state (at 22 months)

- Discharged to nursing facility

- Biochemical analysis of plasma and urine consistent with OTC deficiency (elevated urine orotic acid; plasma glutamine level high; plasma ornithine, citrulline and arginine levels low)

- Genetic testing confirmed OTC gene mutation associated with OTC deficiency

|

|

Patient 2: 39 years old, male

|

|

Medical history

|

|

- Chronic knee pain; no notable family history; high-functioning individual

- Likely precipitant: cortisone injection into knee for knee pain

|

|

Progress

|

|

- Headache, nausea, epigastric pain, blurred vision and incoordination 48 h after injection

- Progressed over next 48 h to confusion, slowed speech

- Progressive decline in GCS, requiring intubation

- Seizure activity

- Repeat CT brain showed cerebral oedema

- Ammonia level: 652 μmol/L (RR, < 50 μmol/L); disease-specific treatment started; intracranial pressure monitor inserted; lack of control of intracranial hypertension; decision to palliate

|

|

Outcome

|

|

- Proceeded to brain death and organ donation (except for liver donation: contraindicated)

- Biochemical findings consistent with OTC deficiency (profound elevation of urine orotic acid, plasma glutamine level high, arginine level low)

- Genetic testing confirmed OTC gene mutation associated with OTC deficiency

|

|

|

GCS = Glasgow coma score; RR = reference range; CT = computed tomography; OTC = ornithine transcarbamylase.

|

Box 2 –

Ammonia levels in our two patients, and their response to treatment*

more_vert

more_vert