Clinical record

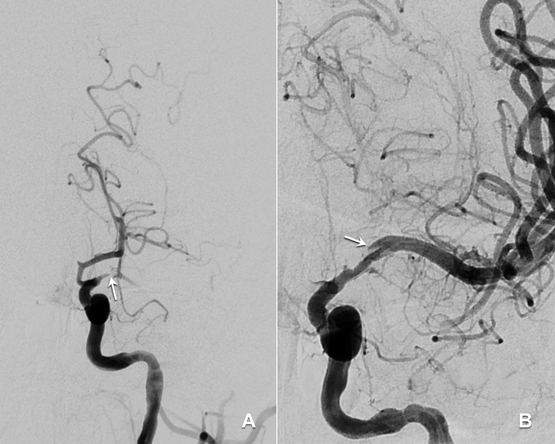

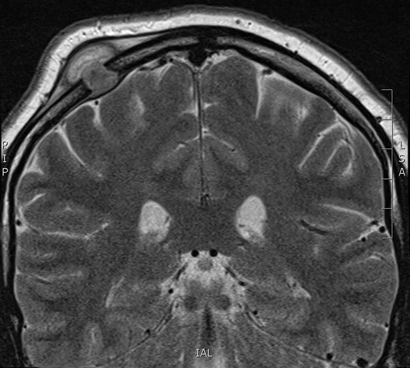

A 33-year-old man presented to an emergency department with acute dysphasia and a dense right hemiparesis. His National Institute Health Stroke Scale score was 12, indicating a moderate severity stroke (score range 0–42, with increasing values indicating increasing severity). His computed tomography (CT) brain scan was normal. A CT angiogram showed a filling defect in the left intracranial internal carotid artery. Intravenous thrombolysis was commenced 2.5 hours after stroke onset and completed during urgent transit to our hospital for endovascular thrombectomy. Combined stent retrieval and suction thrombectomy of the left internal carotid occlusion restored flow 4.5 hours after stroke onset. A small dissection in the left intracranial internal carotid artery was the source of the thrombotic occlusion (Figure). A magnetic resonance imaging scan of the brain showed small scattered infarctions in the left middle cerebral arterial territory.

The patient was later found to have a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection that had been diagnosed 5 years earlier but for which he had not sought or received treatment. There was no history of screening for syphilis. He had a remote and brief history of recreational use of methamphetamines and cocaine (more than 12 months previously). He had no other vascular risk factors (non-smoker, normal fasting lipid and blood glucose levels, negative autoimmune serology). His CD4 cell count was 220 × 106 cells/L (reference interval [RI], ≥ 360 × 106 cells/L) and serum quantitative HIV RNA testing revealed 77 400 copies/mL. Hepatitis serology results were negative. Syphilis serology results were positive: reactive rapid plasmin reagin (RPR) with a titre of 1:256; reactive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination (TPPA) assay; and positive syphilis antibody enzyme immunoassay. His cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein level was 1.17 g (RI, < 0.45 g/L) and his white cell count was elevated at 62 μ/L (RI, < 5 μ/L), predominantly due to monocytosis (84%). CSF syphilis serology was positive, with reactive results from the venereal disease research laboratory, TPPA and fluorescent treponemal absorption antibody tests, confirming neurosyphilis. There were no other clinical or radiological features of tertiary syphilis. CSF polymerase chain reaction test results were negative for other pathogens including varicella-zoster virus, John Cunningham virus and tuberculosis. Cryptococcal antigen test results were negative. Other stroke investigations, including transoesophageal echocardiogram, returned negative results.

A 15-day course of intravenous benzylpenicillin (1.8 g, 4-hourly) with prednisone cover (three doses of 20 mg twice daily to prevent Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction) was completed as treatment for neurosyphilis. He received counselling and was commenced on antiretroviral therapy including abacavir–dolutegravir–lamivudine. Contact tracing was performed. The 3-month outcome was excellent, with only minor persistent dysphasic speech errors and a modified Rankin scale score of 1 (range 0–6, with increasing values indicating worse deficit and 6 for death). Progress serum RPR titres were significantly reduced (1:64), indicating a serological treatment response. A recent progress CD4 cell count was 630 × 106/L and quantitative HIV RNA testing revealed < 20 copies/mL.

Studies indicate that HIV infection increases the risk of ischaemic stroke, particularly in young patients (≤ 45 years) with low CD4 cell counts (< 350 × 106 cells/L).1,2 It is important for clinicians to recognise the various mechanisms by which HIV infection predisposes to stroke. These include a direct HIV-induced vasculopathy, and an indirect opportunistic co-infection-related arteritis with organisms such as tuberculosis, syphilis and varicella-zoster virus.2 HIV vasculopathy has been reported in the extracranial and intracranial cerebral circulations and may cause aneurysmal fusiform or saccular dilatation of vessels or a non-aneurysmal vasculopathy manifest by stenosis, occlusion or vasculitis.2–4 Additional factors contributing to stroke risk in HIV include a more frequent smoking history, coagulopathy, increased homocysteine levels and metabolic syndromes associated with antiretroviral therapies, which may result in accelerated atherosclerosis.1,3 Descriptions of intracranial arterial dissection in patients with HIV infection are limited to rare case reports.5 We postulate that HIV and syphilis co-infection in our patient may have caused a vasculopathy-associated intracranial arterial dissection.

The role and safety of intravenous thrombolysis in patients with HIV infection is not established.2,4 Thrombolysis could be theoretically harmful in patients with HIV vasculopathy or co-infection-related arteritis owing to a potential increased bleeding risk from abnormal vessel wall integrity.4 Despite this, intravenous thrombolysis has been used successfully in patients with untreated HIV infection to treat myocardial infarction and, in our patient, to treat acute ischaemic stroke without adverse outcomes.2,4 Clinicians should be aware that endovascular thrombectomy of proximal anterior cerebral circulation clots after intravenous thrombolysis is now evidence-based treatment for acute ischaemic stroke.6 Our case illustrates the “drip, ship and retrieve” concept of acute stroke management; with intravenous thrombolysis (“drip”) commenced at an initial hospital and completed while the patient was transferred (“shipped”) to another hospital for endovascular thrombectomy (clot “retrieval”). At present, only a limited number of stroke centres provide an endovascular thrombectomy service. Reorganisation of existing systems is required to allow rapid access to endovascular thrombectomy for all appropriate patients in Australia.6

This case presents an important reminder that HIV infection is a risk factor for stroke and that HIV testing should be performed in all young stroke patients. A lumbar puncture is recommended for diagnosis or exclusion of co-existing infections including tuberculosis, syphilis and varicella-zoster, which are all associated with vasculopathy in patients with HIV infection.

Lessons from practice

-

HIV infection is an important risk factor for stroke and HIV testing should be performed in all young stroke patients.

-

Patients with HIV infection and stroke should have a lumbar puncture to examine for co-existing opportunistic infections.

-

A diagnosis of neurosyphilis requires a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cell count and protein measurement and serological testing on serum and CSF.

-

There is evidence that the “drip, ship and retrieve” management approach to managing acute ischaemic stroke is effective. However, in patients with known HIV infection, acute stroke should be managed on a case-by-case basis.

more_vert

more_vert