Neurobionics is the science of directly integrating electronics with the nervous system to repair or substitute impaired functions. The brain–computer interface (BCI) is the linkage of the brain to computers through scalp, subdural or intracortical electrodes (Box 1). Development of neurobionic technologies requires interdisciplinary collaboration between specialists in medicine, science, engineering and information technology, and large multidisciplinary teams are needed to translate the findings of high performance BCIs from animals to humans.1

Neurobionics evolved out of Brindley and Lewin’s work in the 1960s, in which electrodes were placed over the cerebral cortex of a blind woman.2–4 Wireless stimulation of the electrodes induced phosphenes — spots of light appearing in the visual fields. This was followed in the 1970s by the work of Dobelle and colleagues, who provided electrical input to electrodes placed on the visual cortex of blind individuals via a camera mounted on spectacle frames.2–4 The cochlear implant, also developed in the 1960s and 1970s, is now a commercially successful 22-channel prosthesis for restoring hearing in deaf people with intact auditory nerves.5 To aid those who have lost their auditory nerves, successful development of the direct brainstem cochlear nucleus multi-electrode prosthesis followed.6

The field of neurobionics has advanced rapidly because of the need to provide bionic engineering solutions to the many disabled US veterans from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars who have lost limbs and, in some cases, vision. The United States Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has focused on funding this research in the past decade.7

Through media reports about courageous individuals who have undergone this pioneering surgery, disabled people and their families are becoming more aware of the promise of neurobionics. In this review, we aim to inform medical professionals of the rapid progress in this field, along with ethical challenges that have arisen. We performed a search on PubMed using the terms “brain computer interface”, “brain machine interface”, “cochlear implants”, “vision prostheses” and “deep brain stimulators”. In addition, we conducted a further search based on reference lists in these initial articles. We tried to limit articles to those published in the past 10 years, as well as those that describe the first instances of brain–machine interfaces.

Electrode design and placement

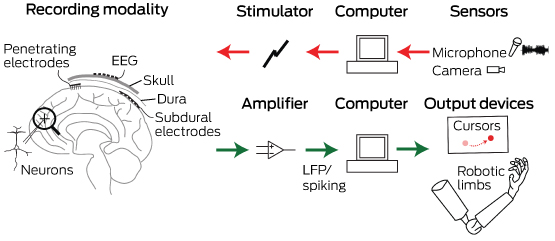

Neurobionics has been increasing in scope and complexity because of innovative electrode design, miniaturisation of electronic circuitry and manufacture, improvements in wireless technology and increasing computing power. Using computers and advanced signal processing, neuroscientists are learning to decipher the complex patterns of electrical activity in the human brain via these implanted electrodes. Multiple electrodes can be placed on or within different regions of the cerebral cortex, or deep within the subcortical nuclei. These electrodes transmit computer-generated electrical signals to the brain or, conversely, receive, record and interpret electrical signals from this region of the brain.

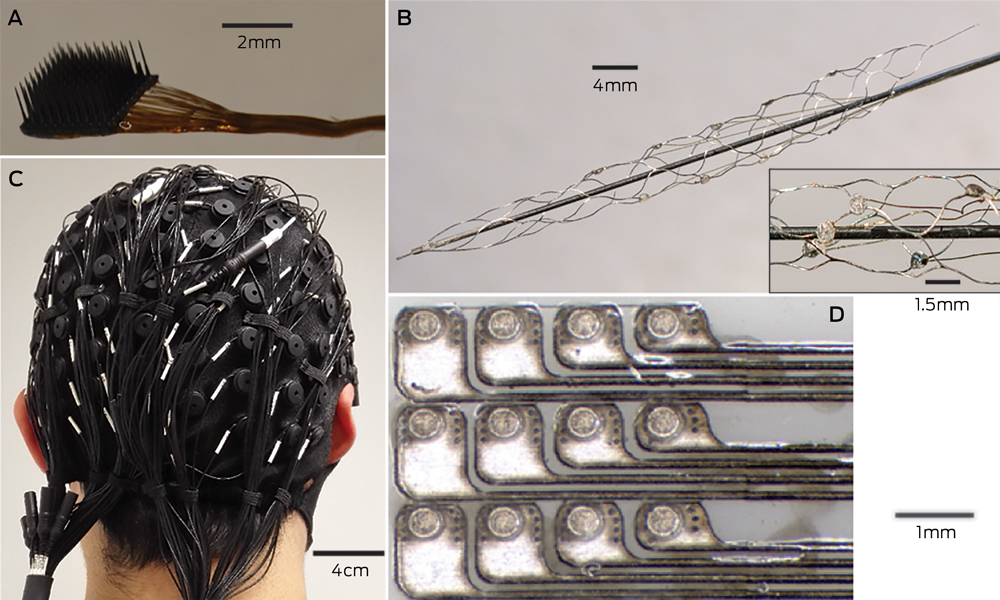

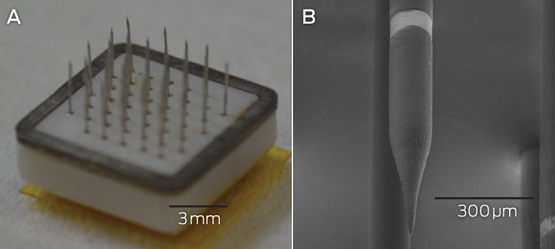

Microelectrodes that penetrate the cortical tissue offer the highest fidelity signals in terms of spatial and temporal resolution, but they are also the most invasive (Box 2, A).8 These electrodes can be positioned within tens of micrometres of neurons, allowing the recording of both action potential spikes (the output) of individual neurons and the summed synaptic input of neurons in the form of the local field potential.9 Spiking activity has the highest temporal and spatial resolution of all the neural signals, with action potentials occurring in the order of milliseconds. In contrast, the local field potential integrates information over about 100 μm, with a temporal resolution of tens to hundreds of milliseconds.

Electrocorticography (ECoG), using electrodes placed in the subdural space (on the cortical surface), and electroencephalography (EEG), using scalp electrodes, are also being used to detect cortical waveforms for signal processing by advanced computer algorithms (Box 2, C, D). Although these methods are less invasive than using penetrating microelectrodes, they cannot record individual neuron action potentials, instead measuring an averaged voltage waveform over populations of thousands of neurons. In general, the further away the electrodes are from the brain, the safer the implantation procedure is, but with a resulting decrease in the signal-to-noise ratio and the amount of control signals that can be decoded (ie, there is a lot of background noise). Therefore, ECoG recordings, which are closer to the brain, typically have a higher signal spatial and temporal resolution than that achievable by EEG.8 As EEG electrodes are placed on the opposite side of the skull from the brain, the recordings have a low fidelity and a low signal-to-noise ratio. For stimulation, subdural electrodes require higher voltages to activate neurons than intracortical electrodes and are less precise for stimulation and recording. Transcranial magnetic stimulation can be used to stimulate populations of neurons, but this is a crude technique compared with the invasive microelectrode techniques.10

Currently, implanted devices have an electrical plug connection through the skull and scalp, with attached cables. This is clearly not a viable solution for long term implantation. The challenge for engineers has been to develop the next generation of implantable wireless microelectronic devices with a large number of electrodes that have a long duration of functionality. Wireless interfaces are beginning to emerge.3,11–13

Applications for brain–computer interfaces

Motor interfaces

The aim of the motor BCI has been to help paralysed patients and amputees gain motor control using, respectively, a robot and a prosthetic upper limb. Non-human primates with electrodes implanted in the motor cortex were able, with training, to control robotic arms through a closed loop brain–machine interface.14 Hochberg and colleagues were the first to place a 96-electrode array in the primary motor cortex of a tetraplegic patient and connect this to a computer cursor. The patient could then open emails, operate various devices (such as a television) and perform rudimentary movements with a robotic arm.15 For tetraplegic patients with a BCI, improved control of the position of a cursor on a computer screen was obtained by controlling its velocity and through advanced signal processing.16 These signal processing techniques find relationships between changes in the neural signals and the intended movements of the patient.17,18

Reach, grasp and more complex movements have been achieved with a neurally controlled robotic arm in tetraplegic patients.19,20 These tasks are significantly more difficult than simple movements as they require decoding of up to 15 independent signals to allow a person to perform everyday tasks, and up to 27 signals for a full range of movements.21,22 To date, the best BCI devices provide fewer than ten independent signals. The patient requires a period of training with the BCI to achieve optimal control over the robotic arm. More complex motor imagery, including imagined goals and trajectories and types of movement, has been recorded in the human posterior parietal cortex. Decoding this imagery could provide higher levels of control of neural prostheses.23 More recently, a quadriplegic patient was able to move his fingers to grasp, manipulate and release objects in real time, using a BCI connected to cutaneous electrodes on his forearms that activated the underlying muscles.24

The challenge with all these motor cortex electrode interfaces is to convert them to wireless devices. This has recently been achieved in a monkey with a brain–spinal cord interface, enabling restoration of movement in its paralysed leg,25 and in a paralysed patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, enabling control of a computer typing program.11

These examples of BCIs have primarily used penetrating microelectrodes, which, despite offering the highest fidelity signal, suffer from signal loss over months to years due to peri-electrode gliosis.26 This scarring reduces electrical conduction and the resulting signal change can require daily or even hourly recalibration of the algorithms used to extract information.18 This makes BCIs difficult to use while unsupervised and hinders wider clinical application, including use outside a laboratory setting.

A recently developed, less invasive means of electrode interface with the motor cortex is the stent-electrode recording array (“stentrode”) (Box 2, B).27 This is a stent embedded with recording electrodes that is placed into the sagittal venous sinus (situated near the motor cortex) using interventional neuroradiology techniques. This avoids the need for a craniotomy to implant the electrodes, but there are many technical challenges to overcome before human trials of the stentrode can commence.

Lower-limb robotic exoskeleton devices that enable paraplegic patients to stand and walk have generated much excitement and anticipation. BCIs using scalp EEG electrodes are unlikely to provide control of movement beyond activating simple robotic walking algorithms in the exoskeleton, such as “walk forward” or “walk to the right”. Higher degrees of complex movement control of the exoskeleton with a BCI would require intracranial electrode placement.28 Robotic exoskeleton devices are currently cumbersome and expensive.

Sensory interfaces

Fine control of grasping and manipulation of the hand depends on tactile feedback. No commercial solution for providing artificial tactile feedback is available. Although early primate studies have produced artificial perceptions through electrical stimulation of the somatosensory cortex, stimulation can detrimentally interfere with the neural recordings.29 Optogenetics — the ability to make neurons light-sensitive — has been proposed to overcome this.30 Sensorised thimbles have been placed on the fingers of the upper limb myoelectric prosthesis to provide vibratory sensory feedback to a cuff on the arm, to inform the individual when contact with an object is made and then broken. Five amputees have trialled this, with resulting enhancement of their fine control and manipulation of objects, particularly for fragile objects.31 Sensory feedback relayed to the peripheral nerves and ultimately to the sensory cortex may provide more precise prosthetic control.32

Eight people with chronic paraplegia who used immersive virtual reality training over 12 months saw remarkable improvements in sensory and motor function. The training involved an EEG-based BCI that activated an exoskeleton for ambulation and visual–tactile feedback to the skin on the forearms. This is the first demonstration in animals or humans of long term BCI training improving neurological function, which is hypothesised to result from both spinal cord and cortical plasticity.33

The success of the cochlear prosthesis in restoring hearing to totally deaf individuals has also demonstrated how “plastic” the brain is in learning to interpret electrical signals from the sound-processing computer. The recipient learns to discern, identify and synthesise the various sounds.

The development of bionic vision devices has mainly focused on the retina, but electrical connectivity of these electrode arrays depends on the recipient having intact neural elements. Two retinal implants are commercially available.3 Retinitis pigmentosa has been the main indication. Early trials of retinal implants are commencing for patients with age-related macular degeneration. However, there are many blind people who will not be able to have retinal implants because they have lost the retinal neurons or optic pathways. Placing electrodes directly in the visual cortex bypasses all the afferent visual pathways.

It has been demonstrated that electrical stimulation of the human visual cortex produces discrete reproducible phosphenes. Several groups have been developing cortical microelectrode implants to be placed into the primary visual cortex. Since 2009, the Monash Vision Group has been developing a wireless cortical bionic vision device for people with acquired bilateral blindness (Box 3). Photographic images from a digital camera are processed by a pocket computer, which transforms the images into the relevant contours and shapes and into patterns of electrical stimulation that are transmitted wirelessly to the electrodes implanted in the visual cortex (Box 3, B). The aim is for the recipient to be able to navigate, identify objects and possibly read large print. Facial recognition is not offered because the number of electrodes will not deliver sufficient resolution.2 A first-in-human trial is planned for late 2017.2,34

The lateral geniculate nucleus of the thalamus is an alternative site for implantation of bionic vision devices. Further technical development of the design, manufacture and placement of multiple brain microelectrodes in this small deep brain structure is needed before this could be applied in humans.35

Memory restoration and enhancement

The same concepts and technologies used to record and stimulate the brain in motor and sensory prostheses can also be applied to deeper brain structures. For example, the fornix is an important brain structure for memory function. A human safety study of bilateral deep brain stimulation of the fornix has been conducted in 42 patients with mild, probable Alzheimer disease (ADvance trial), and this study will now proceed to a randomised controlled trial.36 This technique involves deep brain stimulation without direct feedback from neural recording.

A more definitive approach to memory augmentation would be to place a multi-electrode prosthesis directly into the hippocampus. Electrical mimicry of encoded patterns of memory about a task transmitted from trained donor rats to untrained recipient rats resulted in enhanced task performance in the recipients.37,38 This technology has been applied to the prefrontal cortex of non-human primates.39 Although human application is futuristic, this research is advancing rapidly. A start-up company was formed in 2016 to develop this prosthetic memory implant into a clinic-ready device for people with Alzheimer disease.40 The challenge in applying these therapies to Alzheimer disease and other forms of dementia will be to intervene before excessive neuronal loss has occurred.

Seizure detection and mitigation

Many patients with severe epilepsy do not achieve adequate control of seizures with medication. Deep brain electrical stimulation, using electrodes placed in the basal ganglia, is a treatment option for patients with medically refractory generalised epilepsy.41 Methods to detect the early onset of epileptic seizures using cortical recording and stimulation (to probe for excitability) are evolving rapidly.42 A hybrid neuroprosthesis, which combines electrical detection of seizures with an implanted anti-epileptic drug delivery system, is also being developed.43,44

Parkinson disease and other movement disorders

Deep brain stimulation in the basal ganglia is an effective treatment for Parkinson disease and other movement disorders.45 This type of BCI includes a four-electrode system implanted in the basal ganglia, on one or both sides, which is connected to a pulse generator implanted in the chest wall. This device can be reprogrammed wirelessly. Novel electrodes with many more electrode contacts and a recording capacity are being developed. This feedback controlled or closed loop stimulation will require a fully implanted BCI, so that the deep brain stimulation is adaptive and will better modulate the level of control of the movement disorder from minute to minute. More selective directional and steerable deep brain stimulation, with the electrical current being delivered in one direction from the active electrodes, rather than circumferentially, is being developed. The aim is to provide more precise stimulation of the target neurons, with less unwanted stimulation of surrounding areas and therefore fewer side effects.46

Technical challenges and future directions

Biocompatibility of materials, electrode design to minimise peri-electrode gliosis and electrode corrosion, and loss of insulation integrity are key engineering challenges in developing BCIs.47 Electrode carriers must be hermetically sealed to prevent ingress of body fluids. Smaller, more compact electronic components and improved wireless interfaces will be required. Electronic interfaces with larger numbers of neurons will necessitate new electrode design, but also more powerful computers and advanced signal processing to allow significant use time without recalibration of algorithms.

Advances in nanoscience and wireless and battery technology will likely have an increasing impact on BCIs. Novel electrode designs using materials such as carbon nanotubes and other nanomaterials, electrodes with anti-inflammatory coatings or mechanically flexible electrodes to minimise micromotion may have greater longevity than standard, rigid, platinum–iridium brain electrodes.48 Electrodes that record from neural networks in three dimensions have been achieved experimentally using injectable mesh electronics with tissue-like mechanical properties.49 Optogenetic techniques activate selected neuronal populations by directing light onto neurons that have been genetically engineered with light-sensitive proteins. There are clearly many hurdles to overcome before this technology is available in humans, but microscale wireless optoelectronic devices are working in mice.50

Populating the brain with nanobots that create a wireless interface may eventually enable direct electronic interface with “the cloud”. Although this is currently science fiction, the early stages of development of this type of technology have been explored in mice, using intravenously administered 10 μg magnetoelectric particles that enter the brain and modify brain activity by coupling intrinsic neural activity with external magnetic fields.51

Also in development is the electrical connection of more than one brain region to a central control hub — using multiple electrodes with both stimulation and recording capabilities — for integration of data and neuromodulation. This may result in more nuanced treatments for psychiatric illness (such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder), movement disorders, epilepsy and possibly dementia.

Ethical and practical considerations

Implantable BCI devices are in an early phase of development, with most first-in-human studies describing only a single patient. However, the performance of these devices is rapidly improving and, as they become wireless, the next step will be to implant BCIs in larger numbers of patients in multicentre trials.

The prime purpose of neurobionic devices is to help people with disabilities. However, there will be pressure in the future for bionic enhancement of normal cognitive, memory, sensory or motor function using BCIs. Memory augmentation, cognitive enhancement, infrared vision and exoskeletal enhancement of physical performance will all likely be achievable.

The introduction of this technology generates many ethical challenges, including:

-

appreciation of the risk–benefit ratio;

-

provision of adequate and balanced information for the recipient to give informed consent;

-

affordability in relation to the fair and equitable use of the scarce health dollar;

-

inequality of patient access to implants, particularly affecting those in poorer countries;

-

undue influence on physicians and scientists by commercial interests; and

-

the ability to achieve unfair physical or cognitive advantage with the technology, such as enhancing disabled athletes’ performance using exoskeleton devices, military application with the creation of an enhanced “super” soldier, or using a BCI as the ultimate lie detector.52

The introduction of these devices into clinical practice should therefore not proceed unchecked. As the technology transitions from clinical trial to the marketplace, training courses and mentoring will be needed for the surgeons who are implanting these devices. Any new human application of the BCI should be initially tested for safety and efficacy in experimental animal models. After receiving ethics committee approval for human application, the technology should be thoroughly evaluated in well conducted clinical trials with clear protocols and strict inclusion criteria.53

One question requiring consideration is whether sham surgery should be used to try to eliminate a placebo effect from the implantation of a new BCI device. Inclusion of a sham surgery control group in randomised controlled trials of surgical procedures has rarely been undertaken,54 and previous trials involving sham surgery have generated much controversy.55–57 Sham surgery trials undertaken for Parkinson disease have involved placing a stereotactic frame on the patient and drilling of burr holes but not implanting embryonic cells or gene therapy.58–60 We do not believe sham surgery would be applicable for BCI surgery, for several reasons. First, each trial usually involves only one or a few participants; there are not sufficient numbers for a randomised controlled trial. Second, the BCI patients can serve as their own controls because the devices can be inactivated. Finally, although sham controls may be justified if there is likely to be a significant placebo effect from the operation, this is not the case in BCI recipients, who have major neurological deficits such as blindness or paralysis.

Clinical application of a commercial BCI will require regulatory approval for an active implantable medical device, rather than approval as a therapy. It is also important for researchers to ask the potential recipients of this new technology how they feel about it and how it is likely to affect their lives if they volunteer to receive it.61 This can modify the plans of the researchers and the design of the technology. The need for craniotomy, with its attendant risks, may deter some potential users from accepting this technology.

As the current intracortical electrode interfaces may not function for more than a few years because of electrode or device failure, managing unrealistic patient and family expectations is essential. Trial participants will also require ongoing care and monitoring, which should be built into any trial budget. International BCI standards will need to be developed so that there is uniformity in the way this technology is introduced and evaluated.

Conclusions

BCI research and its application in humans is a rapidly advancing field of interdisciplinary research in medicine, neuroscience and engineering. The goal of these devices is to improve the level of function and quality of life for people with paralysis, spinal cord injury, amputation, acquired blindness, deafness, memory deficits and other neurological disorders. The capability to enhance normal motor, sensory or cognitive function is also emerging and will require careful regulation and control. Further technical development of BCIs, clinical trials and regulatory approval will be required before there is widespread introduction of these devices into clinical practice.

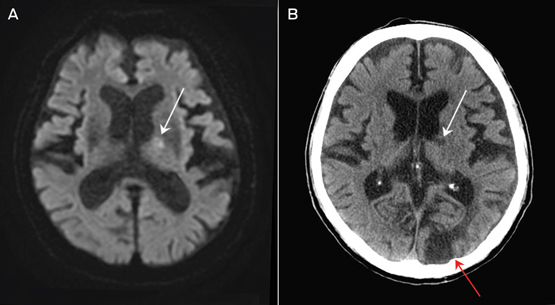

Box 1 –

Schematic overview of the major components of brain–computer interfaces

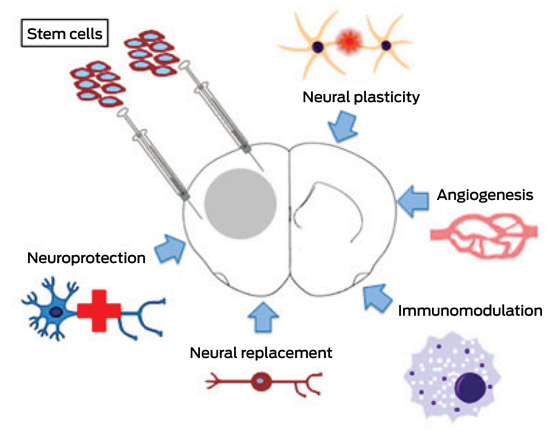

Box 2 –

Electrodes of different scales that can be used to record neural activity for brain–computer interfaces

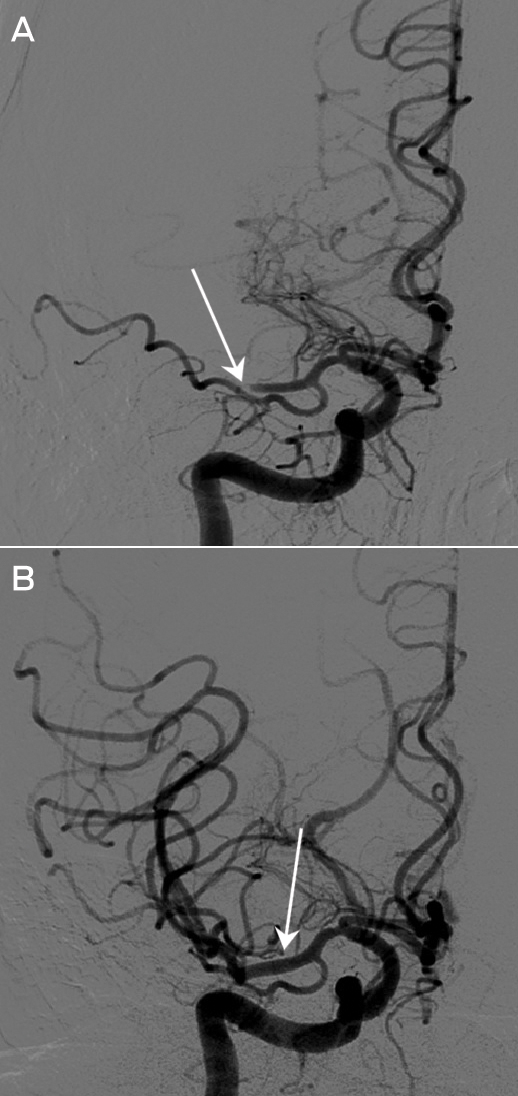

Box 3 –

An example of a fully implantable brain–computer interface

![]() In the meantime, there is enough evidence for doctors to consider referring patients with irritable bowel syndrome for talk therapy and antidepressants.

In the meantime, there is enough evidence for doctors to consider referring patients with irritable bowel syndrome for talk therapy and antidepressants.

more_vert

more_vert