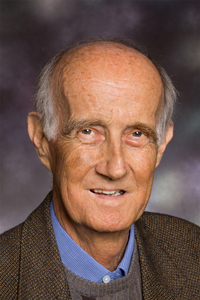

Professor Anthony McMichael will be remembered as much for his warmth, generosity of spirit and dedication to his family as for his work in the fields of environmental epidemiology, public health and climate change science.

Professor McMichael, who died on 26 September 2014 at the age of 71 from complications related to influenza and pneumonia, was regarded as a leader of the pioneering generation of epidemiologists who brought the field to prominence in the 1970s and 1980s.

In his most recent publication for the MJA, Professor McMichael led a dozen prominent Australian medical practitioners and researchers as signatories to an open letter to the Prime Minister, urging action and inclusion on climate change (https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2014/201/5/open-letter-hon-tony-abbott-mp).

“I visited Tony in Canberra Hospital a week [before his death]”, wrote Professor Stephen Leeder, Editor-in-Chief of the MJA (http://blogs.crikey.com.au/croakey/2014/09/27/paying-tribute-to-professor-tony-mcmichael-one-of-the-worlds-public-health-champions). “We chatted about letters received at the MJA following publication of his (and colleagues’) open letter … One letter suggested that we were scurrilous fascists and another Russian socialist lackeys. He found this entertaining.

“He was an active writer on environmental matters … the lines were clearly drawn for his outstanding career in environmental epidemiology and public health.”

Professor Bruce Armstrong, currently working at the International Agency for Research on Cancer, said Professor McMichael was “a lovely, generous man”.

“He had always been concerned with trying to have an influence and make a difference in the world”, Professor Armstrong said. “I had the chance this year to work with him on a think tank on climate change and health. It was a wonderful opportunity to spend time with him, to see his influence on the people around him, and to experience the warmth and care of Tony.”

Professor Bob Douglas, from the National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health (NCEPH) at the Australian National University, in delivering the eulogy, praised Professor McMichael’s “nurturing of future leaders”.

Professor McMichael worked at the University of North Carolina, the CSIRO Division of Human Nutrition, the University of Adelaide as Foundation Chair in Occupational and Environmental Health, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and the NCEPH as Director.

He was President of the Public Health Association of Australia in its early days, was a member of the National Better Health Commission, took a leading role in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and, with Professor Graham Vimpani, led research on lead poisoning that ultimately resulted in moves to lead-free petrol.

His 1993 book Planetary overload was considered groundbreaking. “Tony drew together the threads of research across multiple disciplines, arguing that the human species now faced a new threat to its health and perhaps to its survival”, Professor Douglas said.

Professor Colin Butler, one of Professor McMichael’s closest colleagues over the past two decades, wrote: “If we are to survive as an advanced, wise and compassionate species, the work of people like Tony McMichael will increasingly be recognised as fundamental to the shift that we are engaged in” (http://globalchangemusings.blogspot.com.au/2014/09/aj-tony-mcmichael-champion-for.html).

His early mentor and supervisor Dr Basil Hetzel, first Chief of the CSIRO Division of Human Nutrition, wrote that throughout his distinguished career, “Tony was a very popular figure, readily available to colleagues, research students and the community”.

Professor McMichael is survived by his wife Judith and two daughters, Celia and Anna.

more_vert

more_vert