Crack!

How does Jack Frost get to work?

So begin many Christmas parties in Australia, as guests break the ice by pulling Christmas crackers, playing with the prizes and donning the easy-to-tear paper crowns found therein. While the groan-inducing jokes about frost, penguins and snowmen may seem out of place in the heat of summer, this tradition is as popular Down Under as in its native Britain. Traditionally, the person left holding the larger portion of the cracker is declared the winner of the prizes and gets to wear the paper crown during dinner. While the prizes are rarely anything to write home about (Box 1, Box 2), guests’ competitive natures are aroused by the activity, and everyone would love to be a winner on their first try.

A natural follow-up to the pulling of crackers, particularly for parties where the guests are of a scientific bent, is to formulate theories on the best strategy to employ for a win. Such theories typically focus on technique and physical strength, but we consider here the possibility that attitude also plays a role. In contrast to the ambition typically found in those who aspire to be crowned king, in this study we investigate whether a “Bah, humbug!” passive–aggressive attitude towards Christmas may be of greater advantage. While such behaviour is typically seen as negative,1,2 it may be that the sports catchphrase “It’s not whether you win or lose, it’s how you play the game” paradoxically results in you winning far more often than losing.

Methods

Technique or attitude?

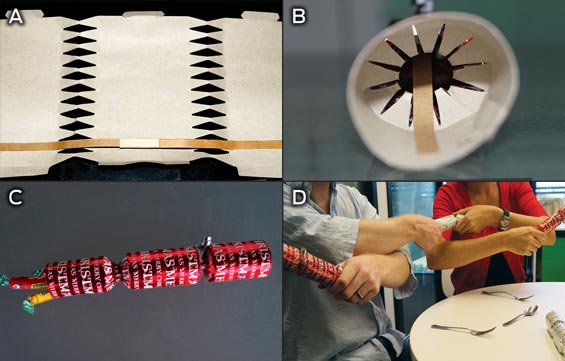

We first considered physiological features that might affect the application of stress (a commodity in ample supply at Christmas time). A cracker is made of a cardboard tube wrapped in colourful paper and resembles the shape of a giant sweet (Box 3). A standard cracker measures about 25 cm in length and has a fillable space of 10 cm3 to hold surprises: small gifts, jokes and paper crowns to make the partygoers look like Wise Men. The content can vary depending on the type of cracker. While the wrapper of smaller bonbons is twisted to keep the filling inside, there is no twisting involved to seal crackers — instead the seams are perforated at the “twist” and tied off, practically guaranteeing that the cracker will break at one of these sites.

While many anecdotes on how to win at crackers have been traded over Christmas dinners, there has been very little controlled research on the subject. Researchers have previously identified factors influencing the chances of winning the content of a cracker,3,4 including grip, angle, distance to the centre of gravity of the cracker, quality of the cracker, size of the cracker, pull and twist. Both these studies reported the importance of the angle at which the cracker is pulled down (optimally between 20° and 55°), indicating this may be an important factor.3,4 One group of researchers even devised a formula, in which the optimal angle = 11 × circumference ÷ length + 5 × quality of the cracker (1 for cheap, 2 for standard or 3 for premium).3

In this study, we focused on a single type of cracker and therefore ignored the factors relating to quality and size. We tested the following three strategies:

- The QinetiQ strategy: a firm two-handed grip, tilting the cracker between 20° and 55° downwards, and applying a steady force with no torque.4

- The passive–aggressive strategy: a firm two-handed grip at no angle, not pulling at all, and letting the other person do all the work.

- The control strategy: typical of Christmas parties around the world, where both participants pull at no particular angle but roughly parallel to the floor.

Study design

To determine whether any particular strategy had a greater than random chance of a win, we designed a binomial trial. We assumed that the probability of winning on each pull depended primarily on the strategy used, with some variability due to characteristics of the individual pullers. Five volunteers were recruited to pull crackers according to the different strategies, and for each cracker pull, the winner and details of the strategy were recorded. Volunteers were randomly paired, with one individual in the pair implementing a specific strategy and the other simply pulling with a two-handed grip in the opposite direction to the angle dictated by the first individual. Both individuals in the pair implemented the given strategy multiple times to account for individual and pair effects. All factors described above that were not varied for the strategy were held constant between the two individuals.

To estimate the probability of a win by any strategy, we considered the total number of wins divided by the number of pulls employing that strategy.

A power analysis was conducted to determine the necessary number of crackers pulled to declare a strategy as “winning”. For a success rate of 0.9, as would be expected from a “guaranteed” victory strategy,3 only five cracker pulls are required to reject the null hypothesis of a success rate of 1/2. Hence, we allotted sufficient crackers to declare whether each strategy met this criterion, and then randomly divided remaining crackers among strategies. In total, 42 crackers were used in this manner, ensuring sufficient power to test the three strategies even for success rates below 0.9.

Mean probabilities of success for each method were computed as the number of wins divided by total number of trials. Confidence intervals were computed according to the binomial distribution. All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, http://www.r-project.org).

The study did not require ethics approval.

Results

Angling for a win

Results from all three strategies are shown in Box 4. Multiple pullers tested the QinetiQ strategy, with no consistent wins; the probability of success was only 0.40 (95% CI, 0.15–0.65), not significantly different from that expected for random chance. The primary difference between this and the other strategies was the angling of the cracker downwards towards the puller, which we therefore cannot conclude provides an advantage.

To pull or not to pull

The remaining two strategies both involved a cracker being held parallel to the floor, but differed on whether both participants pulled or only one pulled while the other just held on. The control strategy most closely replicated typical behaviour at Christmas parties and, as expected, was the strategy producing results closest to random (probability of a win, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.28–0.79). The passive–aggressive strategy was the most successful strategy (probability of a win, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.76–1.00), where the individual who did not pull but merely held on firmly to the cracker won all but one time. This was the only strategy which could be declared “winning” in our study.

Discussion

During a Christmas-in-July party, we tested existing strategies and identified salient features of cracker pulling that may be used to be crowned king of the Christmas festivities. As the QinetiQ strategy had previously been described as “the perfect way to pull a Christmas cracker”,4 we had high expectations for its success. However, this was not supported by our investigations. In particular, in contrast to previous studies, we ruled out angle as a deciding factor in winning Christmas crackers. Further, we identified a novel passive–aggressive strategy as being the surest path to the crown.

Our study has some limitations. We attempted to account for seasonal trends by conducting our trial in winter. However, as Brisbane winters are substantially warmer than those in England (and, on occasion, English summers as well!), it is possible that our strategies would have different success rates in colder weather. We cannot claim that the passive–aggressive strategy is the only strategy that will increase the chances of winning, as we did not have sufficient power to detect smaller deviations from random chance. However, it does seem that attitude may play a greater role than technique in achieving success with Christmas crackers. It is possible that this result is specific to the brand we used and will not generalise to all types of crackers. However, there is at least anecdotal evidence that this strategy has worked previously,5 although no evidence was given to support this claim.

Finally, we did not account for unintentional biases due to differences between volunteers — for example, one volunteer had never seen a cracker before in his life. This person’s win rate was unusually high, with an average probability of winning of 0.71 (95% CI, 0.52–0.91), significantly different from random chance. No other pullers had unusual prowess or lack thereof at pulling, so we must conclude that this person was influenced by the well documented phenomenon of beginner’s luck. Interestingly, every time this individual pulled against someone employing the passive–aggressive strategy, he lost, in spite of his higher than normal success rate in general.

The traditional approach to cracker pulling sees all guests cross hands and pull crackers with their two neighbours (Box 3, D). With our final five crackers, we attempted to test whether our winning passive–aggressive strategy could be used to ensure success for all guests at once. Hence, all individuals pulled with their right hands, but not their left. Unfortunately, the strategy only achieved success for one person; two others won with both hands and the rest lost with both. While including these trials in our results did not alter the conclusions about any strategies, we omitted them due to the differences in conditions. In particular, only one hand, rather than two, was used for pulling each cracker, and as one of the individuals was left-handed, this may have influenced the success of the test.

The passive–aggressive strategy has important implications for future Christmas parties. First, we note that the strategy is useable by any demographic, as it does not require great strength to implement. Indeed, the passivity of the approach may help to avoid the types of injuries previously accorded to cracker-pulling mishaps.6 Second, the strategy is easy to employ with subtlety, unlike any strategy involving an angle, which must surely arouse suspicions in your pulling partner.

Finally, while the winning strategy does have a high success rate, this is true only if one member of the pair is aware of that fact. If both individuals employ the same strategy, the party could stretch on forever, resulting in a burnt dinner and both hosts and guests in tears. The moral of this is a caution against overindulgence in passive–aggressiveness — while judicious use may win you prizes, overdo it, and your goose will be cooked.

1 Summary of the winning content from the study, including barrettes, plastic rings, toy cars and red lips

2 Cracker jokes: the best of the worst

|

Question

|

Answer

|

|

|

What do you call a train loaded with toffee?

|

A chew chew train

|

|

Why does Santa have three gardens?

|

So he can hoe hoe hoe

|

|

What do you call a penguin in the Sahara desert?

|

Lost

|

|

Why did the tomato blush?

|

It saw the salad dressing

|

|

Where do snowmen go to dance?

|

To a snowball

|

3 Cracker construction and use

4 Results for different cracker-pulling strategies

|

Strategy

|

Angle

|

Pull

|

Wins/crackers pulled

|

Probability of winning (95% CI)

|

|

|

QinetiQ*

|

− 30°

|

Lower

|

6/15

|

0.40 (0.15–0.65)

|

|

Control†

|

0°

|

Both

|

8/15

|

0.53 (0.28–0.79)

|

|

Passive–aggressive‡

|

0°

|

No

|

11/12

|

0.92 (0.76–1.00)

|

|

|

* Strategy involves a downwards angle towards the puller. † Strategy involves both individuals pulling. ‡ Strategy involves one individual just holding on.

|

more_vert

more_vert