Case study

A 74-year-old Sicilian woman was admitted to hospital with stridor and dysphonia in the setting of concurrent upper respiratory tract infection. This was on a background of toxic multinodular goitre that had been treated for 8 years with propylthiouracil, as she had reacted adversely to carbimazole. She had been recommended surgery in the past, but had declined.

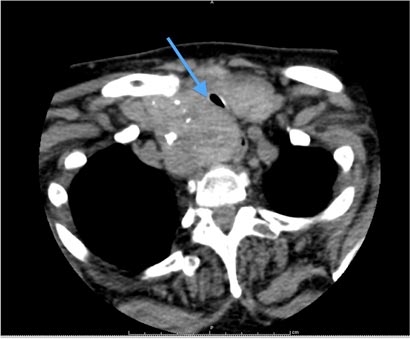

Clinical examination revealed an obvious stridor and a diffuse, symmetrically large goitre. Pemberton sign was positive. Thyroid function tests had demonstrated a suppressed thyroid-stimulating hormone level (0.03 mU/L; reference interval [RI], 0.5–4.0 mU/L), with a free thyroxine level within the RI (16.3 pmol/L; RI, 10.0–19.0 pmol/L). Ultrasound and computed tomography imaging identified a large, retrosternal, multinodular goitre. Her trachea was significantly compressed, with a diameter of 5.5 mm (Box). We further recommended total thyroidectomy, which she again politely declined.

The night after admission, her condition deteriorated acutely and she was transferred to the intensive care unit with respiratory distress. The need for intubation was avoided and she was sufficiently managed with nebulised adrenaline and intravenous dexamethasone. Again, she refused surgery.

She remained in intensive care for the following week, with extensive discussion involving her family (two sons) and the help of Italian interpreters. She was seen by multiple doctors, including senior endocrine surgeons, ear, nose and throat surgeons, intensivists and anaesthetists, all of whom attempted to convey to her the need for surgery. It was made clear that without surgery, she would almost certainly die from tracheal obstruction.

The reasons for her refusal were several, but simple. In her native Sicily, a scar on one’s neck — the Sicilian bowtie — references the Mafia practice of throat-slitting and depicts the scar-carrier as dishonourable. She also expressed her fears of the risks of surgery, particularly voice changes from recurrent laryngeal nerve injury and the need for lifelong medication with thyroxine following thyroidectomy. Further, she was convinced that the reason for her stridor was her upper respiratory tract infection rather than tracheal compression, and believed that it would improve with time.

During this time, every practitioner regarded her to be competent to make this decision. She had an unconventional attitude towards life and death and the implications of surgery, and did not appear to have any cognitive impairment affecting her capacity to consent to or refuse intervention.

Because of the gravity and implication of her decision, we sought a neuropsychological assessment to formally document her capacity before discharge. Much to the surprise of all practitioners involved, the assessment deemed the patient incompetent to make her own decisions regarding treatment. She was assessed as having underlying cognitive impairment and impaired aspects of executive function. With regard to decision making, the assessment found that although “she could state the risks and consequences, she was not adequately and rationally weighing these up against the benefits”. We discussed the assessment with a senior neuropsychologist, who agreed with the initial assessment without any need for reassessment.

We sought advice from the hospital’s legal counsel, who recommended that, because the patient was deemed incompetent, the treatment decision should rest with her sons. In addition, the legal counsel considered neuropsychology to be the most expert opinion in competence assessment and, as such, no further assessment was warranted. Although keen for surgery, her sons were also aware of the implications of forcing their mother into an operation that she did not want. They would have to live with her anger or disappointment long after the acute surgical issues had passed.

After about a week of consideration, her sons consented to surgery. The patient was not informed for fear of an angry outburst leading to sudden airway compromise. Given the patient’s potentially difficult airway and her non-compliance, extensive anaesthetic planning ensued. An anaesthetic team of two senior anaesthetists and an anaesthetic nurse took a difficult airway trolley to the ward, where a heavily sedating premedication was administered and the patient was transferred to theatre. Total thyroidectomy was completed without complication, and the patient made a good postoperative recovery. She was grateful for our care and satisfied with the outcome. She was discharged 2 days later with no stridor, normal voice and normal parathyroid function.

Discussion

This case presented challenging and interesting medicolegal and social dilemmas. We were confronted by a patient with a serious, life-threatening but very treatable medical problem, who was refusing treatment. Moreover, all clinicians involved felt that she had capacity to make this decision, yet the neuropsychological assessment showed otherwise.

Legally, “capacity” and “competence” are interchangeable. At common law, adults are always presumed to be competent, unless it can be proved that they lack competence.1 The test at common law for competence is functional; that is, whether they have the ability to make the decision rather than basing it on criteria or “reasonableness”.2 Generally, the law requires that the patient be able to understand and retain treatment information, believe the information, weigh the information and reach a decision, and communicate his or her decision.1

Based on this common law approach, four jurisdictions in Australia (New South Wales, Queensland, Tasmania and Victoria) have enacted legislation which adopts a functional test of competence.1 In Victoria (the location of this case), s 36(2) of the Guardianship and Administration Act 1986 states:

a person is incapable of giving consent to the carrying out of a special procedure or medical or dental treatment if the person —

(a) is incapable of understanding the general nature and effect of the proposed procedure or treatment; or

(b) is incapable of indicating whether or not he or she consents or does not consent to the carrying out of the proposed procedure or treatment.

Despite the apparent clarity of the legislation, the Victorian Office of the Public Advocate recognises that an assessment of competence is not always straightforward and may require input from specialists such as neuropsychologists, psychiatrists and geriatricians.3 Assessment of competence can often be fraught with complexity. Of patients with underlying mild–moderate cognitive impairment, about 60% of patients remain undiagnosed, even by family members.4 Further, a cognitive test such as the Mini-Mental State Examination has flaws — it is culture-specific and does not address individual cognitive domains well. Complicating this further, acute illness and medication impairs patients’ abilities to synthesise information. The law, as a result of these inherent difficulties in establishing competence, does not require any specific test to be passed, but instead leaves the decision to the discretion of the clinician.1

In cases of incompetent patients, treatment decisions are made by a substitute decisionmaker — a guardian, a medical power of attorney or a person responsible (in our case, the patient’s elder son). In arriving at the treatment decision, the substitute decisionmaker has a responsibility to satisfy either one of two legal standards. The best interest standard involves making a decision in what is considered to be the patient’s best interest (often used for children). The substituted judgment standard relates to patients like ours, who have previously voiced their preference for treatment. Under this test, decisionmakers should attempt to reach the same decision that the patient would have reached had they remained competent.4

Our patient had refused surgery for her thyroid for 8 years before her presentation. She was considered to have capacity then and was never thought to warrant neuropsychological assessment earlier. The substituted judgment standard would suggest that her son should have had this in mind when considering the appropriate treatment approach now.

There has been debate in law about whether some decisions require more competence than others. The prevailing view is that “the more serious the risk, the greater the level of evidence of capacity that should be sought”.4 Some patients may be competent to consent to minor procedures like vaccinations but not competent to consent to major surgery. Unfortunately, there is no guide for doctors to evaluate the level of evidence of competence required for any one particular procedure.

What about our situation, where a patient is judged by doctors as having capacity but by a neuropsychologist as not? When should doctors be satisfied with their own evaluation and under what circumstances should a specialist be engaged on the basis that a higher level of evidence of competence needs to be demonstrated? The law would suggest that specialists in competence assessment (eg, neuropsychologists) should be employed when there is doubt and the consequences are severe. In our case, the patient was considered competent by multiple clinicians. It was only because of the risk of death without surgery that our patient underwent a neuropsychological assessment; many saw this as being an unnecessary step, given her apparent competence. Nevertheless, the severe consequences of inaction justified a comprehensive assessment of competence.

This case also highlights the blurred boundary between capacity and rationality. Our neuropsychologist identified a lack of rationality as one of the reasons for our patient’s incompetence. However, our legislated definition of capacity (stated above) only requires that patients understand; it does not require an assessment of what is rational. Regarding rationality, the Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy states that a “theory of decisional capacity must allow for the fact that health care subjects can make unpopular decisions, even ones that are considered highly irrational by others”.5 Patients must be afforded the right to make seemingly irrational decisions, provided they can understand and appreciate the consequences. An analogy could be made to a Jehovah’s Witness refusing a life-saving blood transfusion; highly irrational to many, this choice is honoured by doctors.

In medicine, we regularly see patients who refuse our recommended treatment. Should we be requesting neuropsychological assessment of all patients refusing our recommendations on the basis that they might be “incapable of understanding the general nature and effect of the proposed procedure or treatment”, as set out in the Victorian Guardianship and Administration Act? To what extent can differences in cultural values cloud the question of whether a patient truly understands the treatment?

These sorts of questions create doubt in the process of assessing capacity and put enormous pressure on doctors making assessments. There is conflict between the doctor’s duty to do what he or she considers to be in the patient’s best interests, while also allowing the patient to make decisions that the doctor considers to be “irrational”. Regarding this conflict, however, the law seems to be clear. In a United Kingdom case, the presiding judge stated: “The doctors must not allow their emotional reaction to or strong disagreement with the decision of the patient to cloud their judgment in answering the primary question whether the patient has the mental capacity to make the decision”.6

Despite her initial reluctance, our patient was happy with her postoperative outcome. We feel that our process was robust and that the appropriate decision was made. But there was still significant unease among the team members that we were operating on a patient against her will. And her satisfaction postoperatively should not be misconstrued as proof that we did the right thing. The right thing is to ensure that a patient’s autonomy is maintained and that we do not confuse our own prejudices with patient competency.

We must remember the social implications of our decisions and interventions. It is not acceptable to consider only the medical issues. Our patients all have unique social circumstances, and our treatments can impact heavily upon these. If our patient refused to speak again to her sons as a result of them consenting to surgery that she had refused, could we consider this a successful outcome?

This case has displayed the many complexities inherent in the assessment of a patient’s capacity to consent to or refuse treatments and interventions. Many social, cultural and legal factors may need to be considered. As clinicians, our understanding of some of these subtleties is limited. Legal principles are complicated and often cases need to be considered carefully on individual merits. Resources such as hospital legal counsel, the Office of the Public Advocate or Guardian (depending on the jurisdiction) and medicolegal handbooks are invaluable in ensuring the protection of both the patient and doctor. In the process of writing this article, our research answered several of the legal questions we had encountered — the answers are available to clinicians if we know where to look. Our experience has taught us to employ the services of multiple teams — medical, psychological and legal — and to engage family in the decision-making process.

more_vert

more_vert