I became Ombudsman to the Lancet journals at the start of 2015, taking over the post from Wisia Wedzicha, who, having been appointed editor of the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, had stepped down at the end of the previous year. To my knowledge I am the first holder of this post not resident in the UK—I was based in Malawi during most of 2015, but relocated to the UK in December.

Preference: Law

558

Compensated transnational surrogacy in Australia: time for a comprehensive review

Reproductive desire, domestic legal restrictions and cost have made transnational surrogacy a lucrative industry.1 Arrangements usually proceed smoothly, but ethical and legal scrutiny of this practice is ongoing. Commissioning parents have allegedly abandoned well2 and unwell3 children born to surrogates overseas. Investigations into transnational surrogacy are numerous, yet we are no closer to an answer as to whether the current status quo is acceptable.

Surrogacy involves a woman (the surrogate) undertaking a pregnancy and giving birth where another individual or couple (the commissioner[s] or intended parent[s]) will parent the child. Where the pregnancy involves the surrogate’s oocyte, it is termed genetic, partial or traditional surrogacy.4 Gestational or full surrogacy occurs when gametes from the intended social parents or a separate donor are used. Surrogacy arrangements that do not result in net financial gain for the surrogate are referred to as altruistic (or non-commercial4), although the distinction between reimbursement and payment is easily blurred. Altruistic surrogacy is rare in Australia, with only 36 live births in 2013.5 Compensated or commercial arrangements involve payment (beyond mere expenses) in exchange for services. This practice is precluded by law or regulation in all Australian jurisdictions.6

All forms of surrogacy give rise to ethical issues.6 Compensated surrogacy is, however, more ethically contentious than altruistic surrogacy, owing to concerns over exploitation and commodification of women, intended parents and children.4 Concerns about socioeconomic disparities exacerbate these issues. This article focuses on the ethics, law and policy of surrogacy as it applies to Australians commissioning a pregnancy in low-income countries for a fee: a practice that can be termed transnational compensated surrogacy.

Regulation of transnational compensated surrogacy in Australia

Surrogacy is not regulated uniformly in Australia,1 and state and territory regimes have been criticised for the complexities that current oversight gives rise to.7

Altruistic surrogacy is permitted in all Australian states and the Australian Capital Territory, albeit with restrictions in some jurisdictions. Commercial surrogacy is prohibited by statute in all states and the ACT, although payment for reasonable expenses is allowed.8 The Northern Territory has no statutes governing surrogacy, although in order to gain accreditation from the Reproductive Technology Accreditation Committee (RTAC), clinics need to adhere to National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) guidelines that veto commercial surrogacy.6 Draft revisions to the NHMRC guidelines say little about transnational surrogacy other than to stipulate practice standards for Australian clinicians.4

Residents in New South Wales, Queensland and the ACT are liable to be charged with an offence if they engage in compensated surrogacy overseas.9 However, this does not appear to act as a deterrent10 and is difficult to enforce.1 Destination countries include Nepal, Mexico and the Ukraine. Thailand has recently restricted compensated surrogacy to heterosexual couples married for more than 3 years; one of the couple also requires Thai nationality (http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/2015/07/31/new-thai-surrogacy-law-bans-foreigners). India has recently initiated similar legal reforms.11

Transnational surrogacy also has legal complexity for citizenship and legal parentage. Examples of children ending up stateless have been discussed in the literature.12 Obtaining legal parentage following surrogacy can also be complex and there is potential for legal disputes to arise.1,13

The question of exploitation

The NHMRC’s draft revised ethical guidelines on assisted reproductive technology cite concerns over exploitation to condemn commercial surrogacy.4 The concern here is the wrongful or unfair use of a woman to have a child for another for payment.14,15 Focusing on women’s reproductive labour to benefit a commissioning couple may also fail to show appropriate respect,16 particularly given the vulnerability and unequal bargaining power of those who act as surrogates.17

The financial gain from commercial surrogacy could also unjustifiably induce participation, particularly if there is evidence that financial rewards mean poorer women participate when they would not otherwise.17,18 This could also be framed as a concern over “an unfair ‘disparity of value’”15 between the payment made and risks encountered.

A response might be that surrogacy is a contract just like any other, and we only need to ensure the arrangement is entered into autonomously and fairly, including appropriate consent. However, the practicalities of ensuring valid consent in a social context of deprivation and inequality are not simple.14 Further, a contract in which the subject of the exchange is a reproductive service may be ethically distinct from contracts that do not involve this type of exchange. Surrogacy impacts bodily integrity, is a constant commitment for the period of gestation, restricts behaviour, is risky (with potential lasting physical and emotional effects) and leads to the birth of a new individual.

It is also interesting to consider whether exploitation should be objectively or subjectively determined. Whittaker’s work examining surrogacy in Thailand, for example, suggests that women do not see their role as exploitative; surrogacy is “described as a selfless act of Buddhist merit”.19 However, Whittaker also comments that framing commercial surrogacy as meritorious may merely be a new form of exploitation. Any influence that payment has on these attitudes may also be relevant.

Evidence also suggests that there are practices that exploit women acting as surrogates in some overseas countries. Accounts describe unscrupulous operators motivated by profit,20 contracts being worded to exclude surrogate women from decision making,21 and there are concerns about ongoing medical care and advocacy during pregnancy and after the birth.19 There is some evidence of pressure being applied to women to act as surrogates to help provide for their families.21 Around two-thirds of the fees paid for transnational surrogacy goes to agents.22

It therefore seems that at least some current practices of compensated transnational surrogacy have legitimate exploitation concerns, which will render them ethically problematic if not addressed. On the other hand, surrogacy is but one example of wider problems of exploitation in the face of global inequities.14 We need to ask both whether (and if so, how) we can improve equality and women’s status in transnational surrogacy contracts and how we can also improve surrogates’ material circumstances,17 including ensuring the utmost medical care and appropriate action if harm occurs.

The question of commodification

Commodification can be defined as occurring when surrogates, the services they provide or the children who are born through surrogacy are wrongfully treated as commodities (a product that can be bought and sold).15 The draft NHMRC guidelines cite this as the second main ethical justification for condemning compensated surrogacy.4 Commodification questions arise in all paid surrogacy, but are particularly prevalent in transnational surrogacy due to disparities in relative wealth. Two main questions arise. First, is compensated transnational surrogacy “baby selling”? Second, does it commodify women?

Critics of compensated surrogacy often turn to claims based on “buying children”. Article 2a of an Optional Protocol to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (ratified by Australia) includes any act of child transfer for remuneration in its definition of the sale of children,23 and some have suggested that legal difficulties in separating payment for a child and payment for reproductive services mean that surrogacy has to be a form of child purchase.15 Additionally, surrogacy contracts often include clauses such that less is paid if a live baby is not surrendered to the commissioning couple.

Wilkinson rejects the claim that surrogacy is “baby selling” on numerous grounds.14,15 One is that a surrogate does not own the baby (insofar as anyone can do this); the commissioning parents do. A handover clause also does not make surrogacy baby selling; it makes it a service contract with a success clause.

As to commodification, conceiving and bearing a child is an intimate process.24 Adding a price could mean that women become mere “wombs for rent” by their commissioners. Wilkinson replies that including a fee-paying aspect does not preclude treating surrogate women with respect. It is the inappropriate use of compensated surrogacy that is commodifying, not compensated surrogacy itself.

It might also be claimed that reproductive labour is just one of many processes for which financial exchange often takes place without demeaning outcomes. Placing children into the care of others, for example, is an intimate and valuable parenting activity for which payment is made. Moreover, not all women may value the intimacy of gestation and labour; or, if they do, they are willing to relinquish this value to another.

Welfare concerns and obligations

Concerns exist around parental obligation and child welfare after transnational surrogacy. For example, if an overseas surrogate is found to be carrying twins, should a commissioning couple take both children? What should happen when a commissioning couple separates during the pregnancy and neither wants the child?

The best interests of the child standard might help answer these kinds of questions. However, the standard itself is liable to criticisms, such as it being vague, or setting a standard that is too high, or being too relative to a particular culture — leaving no room for objective assessment.25 It is difficult to define what is in the best interests of a child conceived via transnational compensated surrogacy. And it could also be claimed that meeting basic interests is enough.

An alternative approach might be to focus on parental obligations. These are applicable to those “who assume the role of a parent” or a person “who has a continuing obligation to direct some important aspect (or aspects) of a child’s development”.26 They include duties such as supporting a child’s development, fulfilling the child’s needs, showing respect, providing primary goods, fostering autonomy and providing advocacy.26,27

Commissioning parents would be subject to these parental obligations, as they have assumed a parental role. The obligation could also be said to be continuing, given that their actions have had a direct causal relationship to the child being born. Commissioning parents who have more children than they can look after or who abandon a child arguably have failed to uphold their parental obligations. The only way parental obligations might end is if a commissioning parent makes appropriate and legal arrangements for another to take on the role instead.

Domestic compensated surrogacy?

Proposed revisions to NHMRC guidelines maintain opposition to compensated surrogacy.4 However, Everingham and colleagues have claimed that the resulting exodus of Australians abroad is a failure of domestic policy.10

How might we respond to this? First, it might be claimed that the status quo could be preserved, perhaps with increased visibility of altruistic surrogacy. However, this would mean that Australians continue to travel for surrogacy, with the risks that this entails,28 the ethical problems it results in and the possibility of prosecution.

An alternate option is to better regulate transnational surrogacy. But we know this is not acting as a deterrent and is poorly enforced.1,18 It may also lead to risks through concealing travel if it were enforced and would require complex agreements between nations.

Third, domestic compensated surrogacy could be sanctioned as a harm-minimisation approach.14,18 Supporters point to factors such as payment being just one factor involved in surrogacy and the inherent commercialisation of assisted reproduction in Australia.18 Regulations could be developed to regulate brokering, fair wages and advertising; the latter is already under consideration in NSW.29

A final option is to take a different ethical approach; for example, by promoting national self-sufficiency.24 This is based on ethical principles such as societal responsibility, solidarity and justice and would involve treating surrogacy in a manner similar to organ donation. However, promoting self-sufficiency does not address the existing low numbers of altruistic donors.

In 2015, the NHMRC invited public comment on fixed payment to Australian oocyte donors beyond reasonable expenses.4 The justification was that many Australians are now travelling abroad and are liable to receive risky or poor-quality treatment. This justification could be said to be a similar harm-minimisation approach to that suggested for surrogacy.14,18 We can therefore question why fixed payment is being considered for oocyte donation in Australia, but not surrogacy.

A nationally coordinated approach to surrogacy may now be on the horizon, with the announcement of a Commonwealth inquiry into surrogacy.30 The inclusion of “compensatory payments” in the terms of reference for the inquiry will hopefully facilitate a thorough and in-depth discussion of these issues nationally. The inquiry is due to report by 30 June 2016.

Conclusion

Transnational compensated surrogacy raises significant ethical and legal issues. It involves balancing surrogates’ and children’s welfare with commissioners’ desires to parent. The present status quo in Australia, with its varying regulations, complexity over legal parentage and concerns over welfare, is problematic. Under both present and proposed regulations, compensated transnational surrogacy will likely continue. Australia needs to do more to ensure that transnational surrogacy is not exploitative or commodifying of surrogates, commissioning parents and children. Parental obligations should also be emphasised in debates over this practice.

Reporting of health practitioners by their treating practitioner under Australia’s national mandatory reporting law

In 2010, the Australian states and territories adopted a national law requiring health practitioners, employers and education providers to report “notifiable conduct” by health practitioners to the appropriate National Health Practitioner Board through the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA). Notifiable conduct encompasses four behaviours: (1) practising while intoxicated by alcohol or drugs; (2) sexual misconduct during the practice of the profession; (3) placing the public “at risk of substantial harm” because of an impairment; or (3) placing the public at risk because of a “significant departure from accepted professional standards”.1 Details of these rules have been published elsewhere.2,3

The mandatory notification law was received with some concern, particularly by doctors and medical professional bodies.2,4 A particularly controversial aspect was its application to practitioners who, in the course of providing care to another practitioner, form a belief that notifiable conduct has occurred. The versions of the law enacted in Western Australia and Queensland allow certain exemptions for practitioners treating other practitioners, but those in force in the other states do not.3

Critics of extending mandatory reporting to care relationships object to the perceived assault on the time-honoured ethics principle of patient confidentiality; they also worry that it will deter impaired practitioners from seeking assistance.5–7 Defenders of the rule argue that treating practitioners have a valuable vantage point from which to identify impaired colleagues, and that requiring them to do so protects the public and enhances trust in the health system.8

Our earlier study of 816 mandatory reports received by AHPRA over a 14-month period2 found that around 8% were made by treating practitioners. In recognition of the importance of these “treating practitioner reports” for policy and practice, we collected and analysed additional data on this subset of reports, and the outcomes of their investigation by AHPRA.

Methods

As part of a larger study of mandatory notification,2 we reviewed all reports received between 1 November 2011 and 31 January 2013. Access to the reports was subject to strict conditions guaranteeing privacy and confidentiality, and study team members signed non-disclosure agreements. The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Melbourne (reference, HREC 1239183.2).

The examined reports were from all states and territories except New South Wales, and had been lodged with AHPRA either in a notification form available on the AHPRA website or in letter form. The layout and content of the reports have been previously described.2 Although health practitioners in NSW are subject to the same reporting requirements as those in other states, AHPRA has a more limited role in relation to notifications made in NSW.2

The reports were reviewed between April and June 2013 at the AHPRA head offices in Melbourne. Three trained reviewers extracted de-identified information about the statutory grounds for notification, the type of problem reported, and practitioner characteristics and demographics. This information was supplemented with data from the national register of health practitioners, including information on sex, age, practice location, profession, and the specialties of both the reporter and the subject of the report.

All reports lodged by a treating practitioner about a practitioner-patient were flagged for more detailed review; they formed the focus of our analysis.

A senior investigator (MB) examined each flagged report to verify that it had been submitted by a treating practitioner. She also extracted any free text that discussed the health condition treated, the nature of the treatment relationship, the perceived risk, and steps the reporter took before lodging their report.

Using a grounded theory approach,9 two investigators (MB, DS) reviewed a subsample of the extracts and developed a coding scheme for deriving information on six variables from the free text: primary health condition for which the patient was being treated; the reporter–patient relationship; the timing of the risk; impediments to risk reduction; advice sought on reporting obligations; and disclosure to the patient of the intent to report. Using the finalised coding scheme, one investigator and a second, legally trained reviewer independently coded the textual extracts for all reports.

Comparison of the data coding by the two coders found inter-rater reliability that ranged from good to very good, depending on the variable. For example, the kappa (κ) score for the variable “impediments to risk reduction”, which probably involved more implicit judgment than the other variables, was 0.77.

In November 2014, the outcomes of the response by AHPRA to each case were obtained and added to the analytic dataset. This allowed 18 to 36 months to elapse after the report lodgement dates.

Statistical analyses were conducted with Stata 13.1 (StataCorp).

Results

Of 846 mandatory reports made to National Boards through AHPRA during the study period, 64 (8%) were lodged by health practitioners who had a treating relationship with the subject of the report. The others were lodged by non-treating practitioners, managers, employers or educators. All results reported here relate to the treating practitioner reports.

Sample characteristics

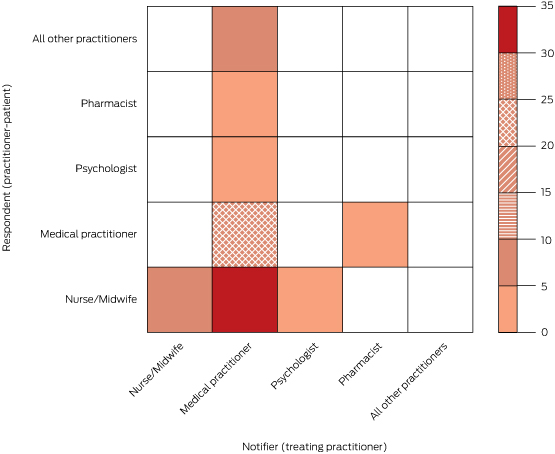

A large majority of the reporters (57 of 64) were doctors, and most of the practitioner-patients were nurses (41 of 64) (Box 1). Two-thirds of the reports by doctors were made by psychiatrists (26 of 57) or general practitioners (16 of 57).

The most common dyads were doctors reporting nurse-patients (35 of 64 cases) and doctors reporting doctor-patients (15 of 64 cases) (Box 2). Nurse reports about nurse-patients were relatively uncommon (5 of 64 cases), although every nurse report involved a nurse-patient.

Grounds for report

Three-quarters of the reports (47 of 64) indicated that the practitioner-patient had placed the public at risk of substantial harm because of an impairment (Box 3). One-fifth of the reports (14 of 64) indicated that the practitioner had practised while intoxicated. Only three reports were triggered by departures from professional standards or sexual misconduct.

Health condition being treated

Practitioner-patients were primarily being treated for mental illnesses (28 of 64), substance misuse disorders (25 of 64) or neurological conditions (9 of 64) (Box 3). The most common forms of mental illness were psychosis, mania and depression. The most commonly misused substances were opiates, benzodiazepines, alcohol and amphetamines.

Nature of treatment relationship

The reporter for one in five reports (14 of 64) was the patient’s regular care provider (Box 4); the others involved treatment encounters with a non-regular care provider. The most common scenario was that the reporter had assumed the role of treating practitioner in the context of an acute presentation to hospital (38 of 64 cases), usually a psychiatric admission (27 of 38 cases). The other scenarios were that the reporter was seeing the patient for the first time (9 of 64 cases) or that the treatment relationship had been established indirectly through an informal corridor consultation (3 of 64 cases).

Other aspects of reports

In most reports (46 of 64 cases), the reporter mentioned discussing the mandatory notification requirement with the patient before the report was lodged. Most reporters (56 of 64) also mentioned that they had sought advice from an indemnity insurer, lawyer, manager or professional peer before making the report.

Twenty-six of the 47 reports of impairment described a risk of harm to the public; 12 of these reports discussed only future risks, six discussed only past risks, and eight discussed both.

Nearly four in five reports (50 of 64) described an impediment to risk reduction. There were four main types of impediment. The most commonly described was that the practitioner-patient lacked insight into the risks posed to patients by conditions such as mania, psychosis, or dementia (29 of 50 cases). A second impediment was deliberate dishonesty with the treating practitioner; this most commonly arose in cases where a practitioner-patient had an addiction and intentionally provided false information to the treating practitioner in an attempt to obtain drugs of misuse (12 of 50 cases). A third impediment was deliberate disregard for treatment advice or patient safety (5 of 50 cases); for example, when a practitioner would not adhere to prescribed medicines or comply with a plan intended to protect patients during the recovery of the treated practitioner. The final impediment to safe management was an ongoing intention to self-harm with medicines that could be obtained in clinical practice (4 of 50 cases).

The 14 reports that did not describe impediments to risk reduction either contained statements indicating that the practitioner-patient had insight into their health condition and was cooperating with treatment (two of these patients had already notified themselves to AHPRA), or there was no relevant information that enabled coding of this variable.

Reponses of reports

By November 2014, National Boards had made a final decision on 86% of the treating practitioner reports (55 of 64). Boards took immediate action in 19 cases. Immediate action is a formal measure that involves placing interim restrictions on practice; it is imposed when this is considered necessary to protect the public pending further investigation.

The final outcomes were: no further regulatory action by a Board (24 of 55 cases); voluntary agreements with the Board and AHPRA regarding appropriate monitoring, treatment or practice restrictions (16 of 54); imposition of formal conditions on the practitioner’s licence (12 of 55); a fine or formal reprimand (2 of 55); and referral to another body for resolution (1 of 55). Although the most common adjudication was to take no further action, it would be erroneous to infer that reports with this outcome were inappropriate or unfounded; steps may have been taken to redress a legitimate concern after the report had been lodged and before the Board’s final decision.

Discussion

Our study of mandatory reports of notifiable conduct by treating practitioners found that 90% were made by doctors, usually psychiatrists or general practitioners, and were typically related to a practitioner-patient who was experiencing mental illness, substance misuse problems or a neurological condition. Relatively few reports were made by regular care providers. Most reports were linked with situations in which the treating practitioner was struggling to safely manage the risk that the practitioner-patient posed, and reporters usually discussed the report with the patient before submitting it.

Australia’s requirement that treating practitioners notify regulators of practitioner-patients with impairments is not unprecedented. New Zealand has required health practitioners to report impaired peers since 2003,10 and several American states have mandatory reporting obligations that extend to treating practitioners.11 However, the Australian legislation is unusually far-reaching in two respects. First, it imposes a duty to report not only health impairments, but also certain concerns about performance. Second, it does not explicitly shield treating practitioners from the obligation to report if the practitioner-patient is participating in an approved program of treatment.

Opponents of mandatory reporting argued that the new requirements would open the floodgates to over-reporting.2 This has not occurred. Mandatory reports are rare events,2 and mandatory reports by treating practitioners are especially infrequent — so infrequent, in fact, that under-reporting is probably a more justifiable concern.

The prevalence of impairment in the health workforce is unknown, but conservative estimates suggest that at least 1000 doctors (about 1% of Australia’s 90 000 registered medical practitioners) are impaired in their ability to practise at some stage in the course of any given year.12–14 Our 15-month sample contained reports on only 16 doctors, and only 20% of the reports were made by the practitioner-patient’s usual care provider. Previous research in the United States and New Zealand suggests that under-reporting of impaired colleagues is widespread,15 even in the context of mandatory reporting laws. Barriers are likely to include loyalty to colleagues, concerns about over-reacting to a situation, and uncertainty about the reporting obligation.16–18

A second objection to the extension of mandatory reporting into the patient–doctor relationship is that it breaches a cornerstone of medical ethics: patient confidentiality. However, the duty to maintain patient confidentiality is not absolute. It is widely accepted that it should yield to obligations to report serious problems or risks that come to light during treatment, including certain infectious diseases, health conditions that imperil driving, and signs of child abuse.19 Whether impairments that pose risks to safe clinical practice are so different from these accepted forms of reporting is debatable. Addressing this issue is beyond the scope of our study, but several aspects of our findings should inform the debate. In particular, the infrequency of treating practitioner reports and the perceived seriousness of the impairments disclosed make it difficult to distinguish the risks associated with practitioner-patient impairment from those of other accepted categories of mandatory reporting by treating practitioners.

Perhaps the most serious charge levelled at the mandatory reporting of practitioner-patients is that it will discourage medical practitioners from seeking assistance.5 This objection involves an empirical question: do the harms that result from treatment foregone because of the law exceed the harms averted by identifying impaired practitioners who would not otherwise have been recognised? Such counterfactuals are difficult to assess. Anecdotal reports suggest that the Doctors’ Health Advisory Services in some states experienced a decline in referrals after the law was enacted.6 But it is not clear whether there was a net decrease across all relevant health services; the question of causality is even less certain. Further, the deferred treatment argument presumes that impaired practitioners would still seek care in the absence of the possibility that they might be reported, but the available evidence suggests that health practitioners may have been reluctant to do so even before the introduction of the law.17,20

When discussing concerns about seeking help, it is worth noting how the reporting behaviour by treating practitioners observed in our study deviated from the exact requirements of the law. The statutory duty to report refers to a past risk of harm and, unlike mandatory reporting programs elsewhere, there is no safe harbour for cases where a practitioner-patient subsequently seeks care and takes appropriate steps to protect patient safety. The pattern of reporting we observed did not correspond with these legal requirements. When explaining their decision to report, treating practitioners were more likely to refer to a future risk of harm than to a past risk. Further, treating practitioners frequently emphasised factors that reduced their ability to work with the practitioner-patient to mutually manage the risk to the public (eg, the patient’s lack of insight, dishonesty or recklessness). Caution is required when making inferences about notifiable conduct that was not reported on the basis of what was reported, but these aspects of the reports, coupled with the very low overall rate of reporting, clearly suggest that treating practitioners resisted reporting their practitioner-patients in circumstances where their treatment was on an appropriate and promising path.

Our study has three main limitations. First, we were unable to directly measure over- and under-reporting. Second, Australia’s mandatory reporting law was implemented in concert with a variety of other major changes to health practitioner regulation, so it was not feasible to assess changes in the rate or nature of treating practitioner reports before and after the introduction of the new law. Finally, we relied on information provided in the reports for most of the variables of interest. To save time or protect confidentiality, some treating practitioners may have omitted or altered salient details. Consequently, the counts we report, particularly for variables that relied on being mentioned in the reports, should be interpreted as lower bound estimates.

Much of the policy debate on the merits of mandatory reporting by treating practitioners has been based on certain implicit assumptions. The standard narrative involves an impaired patient who recognises their illness and seeks treatment from their usual care provider, who must then reluctantly take the contentious step of reporting their patient. Our findings suggest a different picture. The debate should acknowledge several realities. In particular: treating practitioner reports are rare, very few are made in the context of an established treatment relationship, and they tend to occur in situations where there is an identified impediment to safely managing a future risk of harm within the confines of the treating relationship.

Box 1 –

Characteristics of treating practitioners and practitioner-patients involved in mandatory reports

|

|

Practitioner making the notification (treating practitioner) |

Practitioner subject to the notification (practitioner-patient) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Total number |

64 |

64 |

|||||||||||||

|

Profession |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Medical practitioner |

57 |

16 |

|||||||||||||

|

Nurse |

5 |

41 |

|||||||||||||

|

Pharmacist |

1 |

2 |

|||||||||||||

|

Psychologist |

1 |

1 |

|||||||||||||

|

Other* |

0 |

4 |

|||||||||||||

|

Status |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Practitioner |

64 |

59 |

|||||||||||||

|

Student |

0 |

5 |

|||||||||||||

|

Sex |

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

Male |

40 |

20 |

|||||||||||||

|

Female |

23 |

44 |

|||||||||||||

|

Data missing |

1 |

0 |

|||||||||||||

|

Mean age (range), years |

46 (24–62) |

41 (20–81) |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Dentist, physiotherapist, medical radiation practitioner. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 –

Frequency of notifications, by professions of treating practitioner and practitioner-patient

Box 3 –

Statutory grounds for reporting, and health conditions mentioned, for 64 mandatory reports by treating practitioners

|

Statutory grounds for report |

Number of reports |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Have an impairment |

47 |

||||||||||||||

|

Practised while intoxicated |

14 |

||||||||||||||

|

Departure from professional standards |

2 |

||||||||||||||

|

Sexual misconduct |

1 |

||||||||||||||

|

Health condition being treated |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Mental illness |

28 |

||||||||||||||

|

Psychosis/mania |

16 |

||||||||||||||

|

Depression/attempted suicide |

10 |

||||||||||||||

|

Eating disorder |

1 |

||||||||||||||

|

Obsessive–compulsive disorder |

1 |

||||||||||||||

|

Substance misuse |

25 |

||||||||||||||

|

Opiates |

8 |

||||||||||||||

|

Benzodiazepines |

6 |

||||||||||||||

|

Alcohol |

5 |

||||||||||||||

|

Amphetamines |

5 |

||||||||||||||

|

Other (cannabis, cocaine or LSD) |

3 |

||||||||||||||

|

Neurological condition |

9 |

||||||||||||||

|

Dementia/cognitive impairment |

7 |

||||||||||||||

|

Seizures |

2 |

||||||||||||||

|

Unclear |

2 |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 –

Relationship between treating practitioner and the practitioner-patient for 64 mandatory reports by treating practitioners

|

Treating relationship of reporting practitioner to practitioner-patient |

Number of reports |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Regular care provider |

14 |

||||||||||||||

|

General practice |

9 |

||||||||||||||

|

Psychiatry practice |

4 |

||||||||||||||

|

Infectious disease practice |

1 |

||||||||||||||

|

Non-regular care provider |

50 |

||||||||||||||

|

Acute care provider |

38 |

||||||||||||||

|

Psychiatric admission |

27 |

||||||||||||||

|

General medical admission |

2 |

||||||||||||||

|

Emergency department admission |

9 |

||||||||||||||

|

First assessment |

8 |

||||||||||||||

|

Psychiatrist |

4 |

||||||||||||||

|

Physician |

3 |

||||||||||||||

|

Pharmacist |

1 |

||||||||||||||

|

Psychologist |

1 |

||||||||||||||

|

Informal consultation with colleague |

3 |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

[Correspondence] Systematic reviews and research waste

In their letter,1 Ian Roberts and Katharine Ker made three assumptions: that small clinical trials are all of poor quality; that all large, multicentre, well funded trials are of exemplary quality; and that meta-analysis cannot ameliorate the low power of small trials. None of these assumptions are documented. Although many clinical trials do have methodological flaws, many do not, and this issue is addressed in systematic reviews with sensitivity analysis. Certainly, the aims of meta-analysis are to achieve increased statistical power and better quality assessment and to obtain a summary statistic.

Anti-vax dodge a dubious legal ploy

Doctors are being urged not to sign a form being circulated by anti-vaccination campaigners attempting to circumvent new ‘No Jab, No Pay’ laws.

The AMA’s senior legal advisor John Alati said the form, which asks doctors to acknowledge the ‘involuntary consent’ of a parent to the vaccination of their children, used unusual, confusing and misleading wording, and was of dubious legal status.

“This is not a Government-issued form, and there is no legal obligation whatsoever on a doctor to sign it, or even consider it,” Mr Alati said. “It is likely to be meaningless in the legal sense.”

The form has been circulated among anti-vaccination groups ahead of the 2016 school year following Federal Government welfare changes aimed at denying certain welfare payments to parents who refuse to vaccinate their child.

Under the No Jab, No Pay laws, from 1 January this year parents of children whose vaccination is not up-to-date will not be eligible for the Family Tax Benefit Part A end-of-year supplement, or for Child Care Benefit and Child Care Rebate payments. The only exemption will be for children who cannot be vaccinated for medical reasons.

The new laws are aimed at penalising parents who claim a conscientious objection to vaccination, and to provide an incentive for parents who have neglected their child’s vaccination to bring it up-to-date.

The new laws were introduced amid mounting concern that vaccination rates in some areas were slipping to dangerously low levels, increasing the risk of a sustained outbreak of potentially deadly diseases such as measles.

The Australian Childhood Immunisation Register shows there has been a sharp increase in the proportion of parents registering a conscientious objection to the vaccination of their child, from just 0.23 per cent in late 1999 to 1.77 per cent by the end of 2014.

In all, around a fifth of all young children who are not fully immunised are that way because of the conscientious objection of their parents.

The form being circulated by anti-vaccination groups, headed “Acknowledgement of involuntary consent to vaccination”, is intended to circumvent the No Jab, No Pay laws and allow conscientious objectors to receive Government benefits without allowing the vaccination of their children.

But Mr Alati said the dubious nature of the document made it highly unlikely it would be effective in achieving its goal.

He said the very claim of ‘involuntary consent’ in the form’s title was muddled.

“[Consent] may be grudging or doubtful, but if it is given by a person with capacity, apprised of relevant facts, it is consent,” Mr Alati said. “If it is not voluntary, it is presumably not consent.”

In the form, the doctor is asked to sign a statement that “consent provided by (name of parent) is not given ‘voluntarily in the absence of undue pressure, coercion or manipulation’, and hence that, according to Section 2.1.3 Valid Consent of the Australian Immunisation Handbook 10th edition, the consent is not legally valid. Given the absence of valid consent, I am/am not willing to proceed with the vaccination of (name of child).”

Mr Alati said the wording of the acknowledgment was “confusing, to say the least”.

But he warned that although the form was likely to be legally meaningless, its wording was concerning.

He said the fact that it did not include a statement that the doctor had outlined the risks and benefits of vaccination may be used as evidence that the patient was not properly informed of the implications of not being immunised.

And he said the wording of the line “I am/am not willing to proceed with the vaccination of…”, created the false impression that the choice of whether or not to proceed with the vaccination lay with the doctor, not the parent.

Mr Alati said where there was no medical reason for exemption, the doctor’s job was to outline the relevant facts about immunisation and to provide vaccination where consent was given. Where it was withheld, “the doctor should not perform the procedure as it might constitute trespass to the person”.

The AMA legal expert advised doctors presented with the form not to sign it.

“Given the unusual, confusing and misleading wording of the form and its dubious legal status, we do not recommend that any doctor sign it,” he said. “Doctors should explain to the parent or carer that it is their choice whether to proceed with the vaccination, based on what they have been told, and note the situation on the patient’s health record.”

He said any doctor considering signing the form should “carefully weigh up the potential risks of doing so”.

Adrian Rollins

Ley tries to stymie opposition with hep C link

Health Minister Sussan Ley has attempted to stifle opposition to controversial pathology and diagnostic imaging bulk billing incentive cuts by linking the changes to plans to eradicate hepatitis C within a generation.

The Health Minister said a $1 billion initiative to publicly subsidise access to breakthrough hepatitis C drugs had been “fully accounted for” in the mid-year Budget update unveiled on 15 December, but had not been announced at the time to enable confidential price negotiations with the drug companies to be finalised.

Ms Ley confirmed to the Adelaide Advertiser that axing and winding back bulk billing incentive payments for pathology and diagnostic imaging tests – collectively expected to save $650 million over four years – would help fund the subsidy for hepatitis C drugs.

“This demonstrates that the Government is prepared to make the tough decisions to prioritise where we should put our health dollar in Australia,” the Minister said.

By linking the two measures, Ms Ley will make it harder for political opponents of the bulk billing incentive cuts to block the measures in the Senate, where many previous health measures have foundered – most recently proposed changes to the Medicare safety net.

But, while he was “really pleased” hepatitis C patients would get access to potentially life-saving drugs, AMA President Professor Brian Owler warned the Minister she would be “on dangerous ground” if she sought to trade the interests of one group of patients against those of another.

Shadow Health Minister Catherine King told the Adelaide Advertiser that, while she welcomed the decision to list hepatitis C treatments on the PBS, it was “an absurd proposition” to make patients with cancer, diabetes and other serious health conditions pay for the treatment of other seriously ill people.

Professor Owler has criticised the bulk billing cuts, warning that they amounted to a “co-payment by stealth” because they would force pathology companies to begin charging patients a fee.

One of the nation’s largest providers, Sonic Healthcare, has already warned that patients could be charged $20 for a blood test.

Professor Owler said such a co-payment would hit chronically ill patients in need of frequent pathology tests particularly hard, and would discourage many from having diagnostic tests, increasing the risk of more serious health problems later in life.

But Ms Ley has vowed to confront providers over any plans to introduce a co-payment, claiming such a move was “not appropriate”.

She has argued that competitive pressures in the pathology industry meant that companies should absorb the cut, rather than passing it on to patients.

But the pathology market is dominated by two major providers, and the fact that they are contemplating introducing a co-payment suggests the Government’s analysis of the dynamics of the market is flawed.

But the Minister appears confident that she has the upper hand in the politics of the debate, particularly given her move to link the bulk billing incentive cuts to the hepatitis C announcement.

“I have every expectation that Labor will pass these savings, as they make perfect sense – and, particularly, in the context of an announcement like [the hepatitis C initiative],” she told the Australian Financial Review.

Under the measure, the Government will list four new frontline drugs for the treatment and cure of hepatitis C, including sofosbuvir with ledipasvir (Harvoni), sofosbuvir (Sovaldi), daclatasvir (Daklinza), and ribavirin (Ibavyr), on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme from March next year.

The move is expected to benefit around 233,000 people currently infected with the blood-borne virus that attacks the liver causing serious illness, including cirrhosis and cancer. Around 10,000 people are diagnosed with the disease each year, and it responsible for about 700 deaths annually.

The Government’s decision came eight months after the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee recommended that sofosbuvir be listed on the PBS because of “high clinical need”.

This overturned advice from the PBAC a year earlier, in which it recommended against listing the drug because it was likely to have “a high financial impact on the health budget”.

In recommending the drug’s listing, the PBAC warned it was likely to cost taxpayers $3 billion over five years to put 62,000 chronic hepatitis C patients through a course of treatment – three times the Government’s current budgeting.

Though sofosbuvir has been hailed as a “game-changing” medicine that can cure hepatitis C in as little as 12 weeks, its prohibitive price – a course of treatment can cost more than $110,000 – has meant that until now it has been out of the financial reach of most sufferers.

Listing on the PBS means a prescription will cost as little as $37.70 for general patients and $6.10 for concession card holders.

Ms Ley said the combination therapies listed on the PBS had a 90 per cent success rate, and caused fewer side effects than current treatments. She said in most cases patients will only need to take the drug as a pill.

The fact that the Government has budgeted just $1 billion for the measure suggests either that it has managed to negotiate a significant discount with the drug companies, or will eventually need to allocate more money to the effort.

Adrian Rollins

Tribunal snuffs out latest bid against plain packaging

The tobacco industry has lost out in its latest attempt to kill off Australia’s world-leading plain packaging laws.

A bid by tobacco giant Philip Morris to have plain packaging ruled invalid under the terms of Australia’s bilateral investment treaty with Hong Kong has been rejected by the Permanent Court of Arbitration sitting in Singapore.

The ruling is the latest setback for tobacco companies fighting a rearguard action against plain packaging measures, which are being adopted by a growing number of countries, including Britain and Ireland, after coming being enacted in Australia in 2012.

Under the laws, tobacco products must be sold in plain packets carrying graphic health warnings.

The measure has been vehemently opposed by the tobacco industry, which has claimed it infringes on copyright and will drive an increase in trade in illicit tobacco products.

The arbitration ruling means the tobacco industry is running out of legal options to challenge plain packaging.

Soon after the legislation was passed in late 2011, British American Tobacco launched action in the High Court, but its bid was rejected.

Several tobacco-producing countries have also launched action against the legislation under the auspices of the World Trade Organisation, and this bid remains outstanding.

In its latest Position Statement on Tobacco Smoking and E-cigarettes, the AMA said tobacco companies had used packaging to convey messages around social status, values and character, and there were signs that forcing producers to use plain packaging was having an effect rates of smoking.

Related: MJA – The Australian’s dissembling campaign on tobacco plain packaging

A group of studies published in the British Medical Journal found that plain packaging reduced brand appeal and image, and indicated that the proportion of smokers who wanted to quit jumped 7 percentage points following the introduction of plain packaging.

The AMA said that although the measure has not been in place long enough to establish strong evidence of effectiveness, “preliminary research is very promising”.

In addition, it said there was no evidence that plain packaging had led to an increase in the consumption of illicit tobacco.

Adrian Rollins

Latest news:

Deadly attacks raise fears of breakdown in rules of war

Picture credit: IgorGolovniov / Shutterstock.com

Governments and armed groups are being pressured to ensure the safety of patients and health workers in conflict zones amid a spate of high-profile attacks that have left dozens dead and injured.

The World Medical Association, the International Committee of the Red Cross, the World Health Organisation and several other peak health groups have jointly called on national governments and non-state combatants to adhere to international laws regarding the neutrality of medical staff and health facilities, and ensuring this commitment is reflected in armed forces training and rules of engagement.

The call follows an admission by the US military that a deadly attack on a Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) hospital in Kunduz in which 30 people were killed – including 13 staff and 10 patients – was a tragic mistake.

“This was a tragic and avoidable accident caused primarily by human error,” the US’s top commander in Afghanistan, General John Campbell, said, adding that the error was “compounded by systems and procedural failures”.

Though the location of the MSF hospital was widely known, a series of technical and operational errors led the crew of the US gunship that launched the devastating attack to mistake the hospital for the headquarters of the Afghan security service, which had been briefly seized by the Taliban.

The strike co-ordinates for the security building took the aircraft to an open field, so the aircrew decided to launch the attack on the nearest building that matched the description they had been given, which turned out to be the MSF hospital. The aircrew, and the operational command in Kabul, did not check the co-ordinates of the planned target against a “no-strikes” list.

MSF International President Dr Joanne Liu said the incident showed the deadly consequences of any ambiguity about how international humanitarian law applied to medical work in war.

“We need a clear commitment that the act of providing medical care will never make us a target. We need to know whether the rules of law still apply,” Dr Liu said.

The Kunduz attack has added to the urgency for action to be taken to ensure the safety of medical staff and hospitals in combat zones.

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), through its Health Care in Danger project, recorded 2398 attacks on health workers, facilities and ambulances in just 11 countries between January 2012 and the end of last year.

Policy and Political Affairs Officer for the ICRC’s Australian mission, Natalya Wells, said such attacks were not new, and were virtually a daily occurrence.

Ms Wells often health workers were caught in the cross-fire, particularly as a result of indiscriminate attacks in urban areas.

But she said that on occasion they were also being deliberately targeted, underlining the need for all combatants to respect the Geneva Conventions.

Ms Wells said that through the Health Care in Danger project, the ICRC was working with governments, armed forces and non-state combatants to improve awareness of, and respect for, laws and conventions around the protection of patients, health workers and medical facilities, particularly in conflict zones.

As part of the effort, governments attending the 32nd International Conference of the Red Cross and Red Crescent between 8 and 10 December were expected to back a resolution reaffirming their commitment to international humanitarian law and a prohibition on attacks on the wounded and sick as well as health care workers, hospitals and ambulances.

In addition, Ms Wells said the ICRC had held meetings with 30 non-state combatant groups from four continents about international humanitarian law and the rules of armed conflict.

The discussions have included incorporating knowledge of these conventions into their training, backed by sanctions for any breaches.

Promisingly, Ms Wells said that so far “one or two” non-state armed groups, though not signatories to the Geneva Conventions, have discussed creating a similar code of conduct for their forces.

Adrian Rollins

MJA reviewers

Reviewers (submitted between 31/10/2014 and 1/11/2015)

Penelope A Abbott

Ehtesham A Abdi

Sarah J Abrahamson

Leon A Adams

Barbara-Ann Adelstein

Stephen Adelstein

Michael A Adena

Roman A Ahmed

Philip D Aitken

Karyn E Alexander

Charles Algert

Roger WG Allison

Steve J Allsop

Craig S Anderson

Ian P S Anderson

Warwick H Anderson

David Andresen

Gavin Andrews

Anders Aneman

Rachel A Ankeny

John S Archer

Nigel R Armfield

Bruce K Armstrong

Carolyn Anne Arnold

Peter C Arnold

Constantine N Aroney

Rosalie Aroni

Peter Arvier

Michael A Ashby

Eugene Athan

John J Atherton

David N Atkinson

Peter D Baade

Rodney J Baber

Leon A Bach

Tim Badgery-Parker

Peter A Baghurst

Paul M Bailey

Rob Baird

Deborah F Baker

Ross I Baker

Mohammed S Ballal

Zsolt J Balogh

Lilon G Bandler

Michael Barakate

Amanda Barnard

David J Barnes

Andrew Bartholomaeus

Harold Bartlett

Michael B Barton

Darryl L Bassett

Robert G Batey

Malcolm W Battersby

Peter E Baume

Justin J Beilby

Anthony J Bell

Narelle Bell

Christine C Bennett

Jill Benson

Roy G Beran

Yemima Berman

Martin Berry

Andrew D Bersten

James D Best

John B Best

JH Nicholas Bett

Laurent Billot

Sara Bird

Roderick O Bishop

Renee Bittoun

Deborah A Black

David J Blacker

Christopher F Bladin

Neville Board

Felix Bochner

E Leslie Bokey

Stephen N Bolsin

Patrick GM Bolton

Chelsea J Bond

Michael A Bonning

Barbara J Booth

Robert Booy

Craig S Boutlis

Steven J Bowe

Simon D Bowler

Anne-Marie Boxall

Steven C Boyages

Ian W Boyd

Frances M Boyle

Michael J Boyle

Clare E Bradley

George Braitberg

Jeffrey Braithwaite

Annette J Braunack-Mayer

Bruce J Brew

David B Brieger

Esther Briganti

Nancy E Briggs

Julie K Brimblecombe

Helena C Britt

Henry Brodaty

Wendy E Brodribb

Julia ML Brotherton

Jamie Bryant

David J Buckley

John F Buckley

Stephen R Buckley

Michael D Buist

Chris Bullen

Jonathan GW Burdon

Paul Burgess

John Burke

Bryan H Burmeister

John R Burnett

Colin D Butler

Julie E Byles

Joshua Byrnes

Petra T Bywood

John F Cade

Dominique A Cadilhac

J William F Cairns

W Ian Cameron

David G Campbell

Dianne Campbell

Patricia Campbell

Terence J Campbell

Gideon A Caplan

Magnolia Cardona-Morrell

Marion G Carey

John B Carlin

John Carmody

Vaughan J Carr

Gerard E Carroll

Phillip J Carson

Owen BJ Carter

Ian D Caterson

Steven J Chadban

Leanne Chalmers

Alex J Chamberlain

Albert KF Chan

Lewis Chan

Raymond C Chan

Michael G Chapman

Alex Chaudhuri

Ruchir Chavada

Celia S-W Chen

Allen C Cheng

Ian R Cheong

Derek PB Chew

Cherie Ying Chiang

E Mary Chiarella

Jun Chih

Tanya N Chikritzhs

James YJ Choi

Patty Chondros

Tim Churches

Flavia M Cicuttini

Jonathan Clark

Stephen L Clark

Caroline F Clarke

Stephen J Clarke

Moira A Clay

Alan R Clough

Stephen Colagiuri

Justin J Coleman

Peter J Collignon

Veronica R Collins

Brian T Collopy

David M Colquhoun

Tracy Comans

Elizabeth J Comino

Jennifer J Conn

Mark Connor

Matthew C Cook

Michael D Coory

William Coote

Charles F Corke

Marcello Costa

Sophia Couzos

Brendon J Coventry

Terry J Coyne

Shona Crabb

Maria E Craig

Pippa Craig

Helen M Creasey

T John Croese

Louise Cullen

Anthony L Cunningham

Frances C Cunningham

Bart J Currie

David Currow

Eleonora Dal Grande

Luciano Dalla Pozza

Andrew Dalton

Seamus E Dalton

ER David Dammery

Santosh Daniel

John Daniels

Lynne A Daniels

Anthony M Dart

Mike Daube

Sandra K Davidson

Lucy Davies

Gavin A Davis

Ian D Davis

Joshua S Davis

Andrew H Dawson

Carolyn A Day

Richard O Day

John F de Campo

Caroline M de Costa

Nicholas H de Klerk

Christopher B Del Mar

Geoff Delaney

Martin B Delatycki

Apo Demirkol

Justin T Denholm

Catherine A D’Este

Karen M Detering

Peter G Devitt

Jan E Dickinson

Hugh G Dickson

Paul M Dietze

John B Dixon

Gordon Doig

Xenia Dolja-Gore

Leo T Donnan

Kirsty Douglas

Jo A Douglass

Susan M Dovey

Michael A Downes

Robert P Dowsett

Tim R Driscoll

Dino Druda

Olaf H Drummer

Stephen J Duckett

Michael J Dudley

Anne E Duggan

James A Dunbar

Peter Dwyer

John R Dyer

Peter R Ebeling

Matthew Edwards

Paul V Effler

Sam Egger

John A Eisman

Elif I Ekinci

Diann S Eley

Jaklin A Eliott

Steven R Ellen

Pete M Ellis

David A Ellwood

Adam G Elshaug

Jon D Emery

Michael WN Epstein

Sue M Evans

Mark Everard

Ben D Ewald

Daniel P Ewald

Paul A Fagan

Paul P Fahey

Christopher K Fairley

Michael Falster

Elizabeth A Farmer

Anne-Maree Farrell

Michael Farrell

A Michael Fasher

Thomas A Faunce

Steven G Faux

Michael R Fearnside

John K Ferguson

David W Firman

Kenneth D Fitch

Gerard J FitzGerald

Mark C B Fitzgerald

Paul B Fitzgerald

Arthas Flabouris

Jeff Flack

Maree Flaherty

Louisa Flander

John I Fleming

John P Fletcher

Leon Flicker

Eleanor M Flynn

Brett H Forge

S Lesley Forster

Craig L Fry

Gordian WO Fulde

John S Furler

Belinda J Gabbe

Jamie Gaida

Alexander S Gallus

Glenn J Gardener

Alan Garner

Paul H Gavel

Kurt Gebauer

Charles RP George

Emma Gibbs

John Gibson

Heather F Gidding

Gwendolyn L Gilbert

Marisa T Gilles

Rodney C Givney

Nicholas J Glasgow

Katie Glass

Sharon R Goldfeld

John M Goldsmid

Phillip D Good

J Jill Gordon

Louisa Gordon

Alexandra S Gorelik

C Roger Goucke

Linda V Graudins

Angus J Gray

Timothy J Gray

M Lindsay Grayson

Anthony J Green

Shaun L Greene

David Greenfield

Jerry R Greenfield

Paul F Gross

Russell L Gruen

Sylvia Guenther

Charles S Guest

Hasantha Gunasekera

Leena Gupta

Steven L Guthridge

Paul S Haber

Sandra M Hacker

Kay Haig

Ian E Haines

George Halasz

Sally J Hall

Wayne D Hall

P Shane Hamblin

Ian R Hamilton-Craig

Alan W Hampson

Graeme J Hankey

Terry J Hannan

Richard W Harper

Todd Harper

David C Harris

Ian A Harris

John Harris

Mark F Harris

Phillip J Harris

Gunter Hartel

Mary Anne Hartley

Melissa Haswell-Elkins

Andrew Hayen

Noel E Hayman

Christopher H Heath

Debra Hector

William F Heddle

Edward B Heffernan

Delia V Hendrie

Geoffrey Henley

Ana Herceg

Wayne M Herdy

Richard P Herrmann

Ian B Hickie

David R Hillman

Sara Hitchman

Christopher D Hogan

Patrick G Hogan

John D Horowitz

Robert L Horvath

Kenneth F Hossack

Anthony K House

Benjamin P Howden

Laurie G Howes

Wendy E Hoy

Rae-Lin Huang

Ben Hudson

Bernard J Hudson

J Nicoll (Nicky) Hudson

Lisa Hui

John S Humphreys

Joseph Hung

Roger W Hunt

David Hunter

Ernest M Hunter

Jennifer Hunter

Elizabeth Hurrion

Sarah J Hyde

Zoe Hyde

Susan Ieraci

Warrick J Inder

Timothy JJ Inglis

Timothy W Isaacs

Geoffrey K Isbister

James P Isbister

Alan F Isles

Rebecca Q Ivers

Claire L Jackson

Paul Jagals

Ian James

Stephen Jan

Tania Janusic

George Javorsky

Gary P Jeffrey

V Michael Jelinek

Paul Jennings

George Jerums

Ian Johnson

Paul DR Johnson

Renea Johnston

Barbara F Jones

D Gareth Jones

D Brian Jones

Mark A Jones

Michael Jones

Penelope Jones

Anthony F Jorm

Matthew D Jose

Rodney T Judson

Stephen M Jurd

Jon N Jureidini

Ian J Kamerman

Leah Kaminsky

Melissa S-L Kang

Andrew H Kaye

Damien Kee

Marc JNC Keirse

Margaret A Kelaher

Heath A Kelly

Lisa Kelly

Robert I Kelly

Michael C Kennedy

Peter G Kerr

Ian H Kerridge

Alison M Kesson

Michael R Kidd

Monique Kilkenny

Thomas E Kimber

Stuart A Kinner

Adrienne C Kirby

Stephen Kleid

Timothy Kleinig

Christopher S Kneebone

Andrew W Knight

Bogda Koczwara

Ann P Koehler

Jen Kok

Pieter J Koorts

Steven Kossard

Joe M Kosterich

Gabor T Kovacs

Emma E Kowal

Vicki L Krause

Edwin Kruys

Paul A Kubler

Dennis L Kuchar

Maarit Laaksonen

Matthew M Large

Sarah L Larkins

Ann-Claire Larsen

Murray Laugesen

Gillian A Laven

Amanda J Leach

Karin Leder

Katherine Lee

Richard P Lee

Peter A Leggat

James Leigh

Christopher Lemoh

Nat P Lenzo

David E Leslie

Lucy N Lewis

Simon Lewis

Steven J Lewis

Shu Qin Li

Wenbin Liang

Ee Mun Lim

Wendy L Lipworth

Mark Little

Sing Kai Lo

Bebe Loff

David FM Looke

Charles W Lott

Clement Loy

Michaela Lucas

Kehui K Luo

Sharyn Lymer

Kristine Macartney

Graeme A Macdonald

Peter S MacDonald

Jennifer H MacLachlan

William (Bill) J Madden

Guy J Maddern

Ian Maddocks

Dianna J Magliano

Roger S Magnusson

Graeme P Maguire

Donna B Mak

Lynette M March

Peter G Markey

Tania Markovic

Guy B Marks

Alexandra L Markwell

Julia V Marley

Andrew J Martin

Alison Marwick

Colin L Masters

John D Mathews

John JS Mattick

Jeremy M McAnulty

Grant McArthur

Brian R McAvoy

Kristin E McBain-Rigg

W John H McBride

Geoffrey W McCaughan

Kieran A McCaul

Geoffrey J McColl

Judith McCool

Joseph G McCormack

Robyn Anne McDermott

Peter J McDonald

Michael A McDonough

Neil W McGill

Diana R McKay

Joanne E McKenzie

Mary-Louise McLaws

Hamish McManus

Donald McNeil

Barbara McPake

Jacqueline K Mein

Craig Mellis

Muhammed A Memon

Richard M Mendelson

J Alasdair Millar

Jeremy L Millar

Belinda R Miller

Emma R Miller

Graeme C Miller

Roger Laughlin Milne

I Harry Minas

Adrian Mindel

Philip B Mitchell

Mohammadreza Mohebbi

Michael Montalto

A Rob Moodie

David J Moore

Elizabeth M Moore

Rachael Moorin

Susan J Morgan

Robert FW Moulds

Alison M Mudge

Sandy Muecke

Wendy Muircroft

H Konrad Muller

Raymond J Mullins

Kevin Murray

Richard B Murray

Arthur (Bill) W Musk

Ludomyr J Mykyta

Balakrishnan (Kichu) R Nair

Mark R Nelson

Peter W New

Jonathan W Newbury

Louise K Newman

Harvey H Newnham

Ainsley J Newson

Hanh TT Ngo

Peter K Ngo

Cattram Nguyen

Kathleen M Nicholls

Marcus Nicol

Suzanne Nielsen

Paul Nisselle

Theophile (Theo) Niyonsenga

Antony Nocera

David A Nolan

Terence M Nolan

Don Nutbeam

Cornelius (Kees) M Nydam

Diana O’Halloran

Paula O’Brien

Dianne L O’Connell

Rachel L O’Connell

Nicholas J O’Connor

Kerin O’Dea

Jake Olivier

Ian N Olver

Susanne P O’Malley

Liliana Orellana

Peter K O’Rourke

Matthew O’Sullivan

Donald R Packham

Colin B Page

Pamela Palasanthiran

Neil R Parker

William A Parsonage

Sally Partridge

Dennis R Pashen

Anushka Patel

Jillian Patterson

Brian B Peat

David P Peiris

Carmelle Peisah

Brita AK Pekarsky

Stella Pendle

David G Penington

Andrew G Penman

Roger J Pepperell

Martin Pera

Vlado Perkovic

Andrew Perry

Alexandra Phelan

Christine B Phillips

Avinesh Pillai

S Praga Pillay

Hans C Pols

Rene G Pols

P Gawaine Powell Davies

Jennifer R Powers

Douglas A Pritchard

Anthony M Proietto

Brendan Quinn

Michael A Quinn

Janette C Radford

Shripada Rao

William D Rawlinson

Tim RH Read

Andrew M Redmond

Anne Rees

Carole Reeve

Glenn EM Reeves

Alun H Richards

Bernadette J Richards

Brian H Richards

Gary E Richardson

Jeffrey R Richardson

Geoffrey J Riley

Malcolm D Riley

Matthew Rimmer

Ian T Ring

Darren M Roberts

Iain K Robertson

J Owen Robinson

Monica C Robotin

David M Roder

Gary D Rogers

Bronwen Ross

Glynis P Ross

Nicola Ross

Elizabeth E Roughead

George L Rubin

Anthony W Russell

Lesley M Russell

Christopher J Ryan

Louise M Ryan

Michael Ryan

Sabe Sabesan

Gary Sacks

Salih A-S Salih

Shahneen Sandhu

Michael J Sandow

W Peter Saul

Leslie Schrieber

Brenton L Schuetz

Rosalie Schultz

Anthony Scott

Ian A Scott

David J Scrimgeour

Clair Scrine-Bradfield

Paul A Scuffham

Katrina J Scurrah

Eva Segelov

Warwick S Selby

Tarun Sen Gupta

Tim Senior

Jillian R Sewell

William A Sewell

Anurag Sharma

Rashmi Sharma

Mary-Jane S Sharp

Harshvardhan Sheorey

Rupendra N Shrestha

Stephen P Shumack

Kenneth A Sikaris

Morry Silberstein

Gregory Siller

Leon A Simons

Rodney D Sinclair

Andrew H Singer

Dan J Siskind

Freddy Sitas

Peter Sivey

Tim Slade

Adrian Sleigh

Richard A Smallwood

Dale C Smith

David E Smith

David W Smith

Julian A Smith

Karen Smith

Mitchell M Smith

Richard S W Smith

William B Smith

Tim J Smyth

Ann C Solterbeck

Ernest R Somerville

Richard Speare

Denis Spelman

Allan D Spigelman

Geoffrey K Spurling

Piyush M Srivastava

Rosemary A Stanton

David G Steel

Amanda M Stephens

Matthew Stevens

Christopher E Stevenson

Mark Stevenson

Jessica M Stewart

Johannes U Stoelwinder

Mark Stoove

H Victor Storm

Nicholas W Stow

Roger P Strasser

Alison Street

Allan D Sturgess

Danny H Sullivan

David R Sullivan

Suresh Sundram

Rajah Supramaniam

Tatiana Surzhina

Tom R Sutherland

Jeffrey Szer

Michael L Talbot

Chun Wah M Tam

Colman B Taylor

Hugh R Taylor

Peter L Thompson

Sandra C Thompson

James Tibballs

Sean Tobin

Shilu Tong

Steven YC Tong

Robyn Toomath

Adrienne J Torda

Huy A Tran

Brian M Tress

Stephen C Trumble

Philip G Truskett

Bernard E Tuch

Robin M Turner

Ida Twist

Jason A Tye-Din

Flora Tzelepis

Shahid Ullah

Edward Upjohn

Lydia Upjohn

Tim Usherwood

Mieke L van Driel

Helen J Van Gessel

Paul Varghese

Phillip C Vecchio

Mark GK Veitch

Elmer V Villanueva

Ioana Vlad

Russell G Waddell

Victoria (Tori) A Wade

Mark L Wahlqvist

Jennifer Walker

Thomas D Walker

Merrilyn M Walton

Han Wang

Joanna JJ Wang

Zhiqiang Wang

Michael R Ward

Vicki-Ann Ware

Orli Wargon

Lachlan J Warren

D Ashley R Watson

Bruce P Waxman

Peter Wein

Leo Westbury

R Michael Whitby

Andrew V White

Ben White

Ian M Whyte

Bridget Wilcken

Kay A Wilhelm

Garry J Wilkes

Lesley M Wilkes

Dominic JC Wilkinson

Amanda Wilson

Ian G Wilson

Ingrid Winship

Erica M Wood

Fiona M Wood

Peter Wood

Richard J Woodman

Michael C Woodward

Paul S Worley

Roxanne L Wu

Rosemary Wyber

Fenglian Xu

Ian A Yang

Mark W Yates

Bu B Yeap

Josephine Yeatman

Sonia Yip

Doris YL Young

Bing Yu

Kally Yuen

Farhat Yusuf

Jeffrey D Zajac

John R Zalcberg

Nikolajs Zeps

Yuejen Zhao

John B Ziegler

Nicholas A Zwar

Building on the rich heritage of the Medical Journal of Australia

My professional interests span clinical practice, medical education and research, medical leadership, health policy and social justice. My goals as editor are to build on the outstanding DNA of the Journal, further increasing its relevance and readability, and attracting the highest quality submissions. We will aim to build on the Journal’s rich heritage by continuing our practice of publishing the best clinical science papers that have the potential to transform practice, including clinical trials and comparative effectiveness research. We will also aim to inform readers on advances in medical education, and cover issues from medical leadership to re-engineering our health system. We will continue to seek expert reviews, editorials and commentaries, meta-analyses and guidelines, and the latest news and information that everyone in practice needs to know. It is my goal to reinforce the unique role that the Journal plays as the pre-eminent publisher of Australian medical research and as a vital platform for translating research into practice, as well as helping to inform the broader health policy debate. This is part of the Journal’s success and why it is relevant to clinicians, researchers and academics across the nation.

The MJA is prestigious and influential, but another advantage to publishing with us is that much of the content including our research content is published freely on our website at mja.com.au, without the waiting period often imposed by other journals. I can also assure readers that as Editor-in-Chief, I have a guarantee of editorial independence and I will fiercely guard this independence on your behalf. For the nearly 32 000 subscribers who receive the MJA in print, and the many others who read the Journal online, the team will work tirelessly to provide the best medical journal experience possible.

We live in a world that, in terms of connectivity through social media, is rapidly shrinking, and the MJA has an important role to play not just nationally but globally. We will therefore now be encouraging locally relevant international articles. And we will continue to tackle in our pages articles that highlight the tough health issues we all face and provide possible solutions, from the health needs of Indigenous Australians to the health impacts of global migration, population growth, dwindling resources, an ageing population and climate change, to name a few. We will look both out to the world and across Australia to find the objective data that can help guide us all. We will seek balance among the many expert opinions and will aim at all times to be rigorous, evidence-based and transparent.

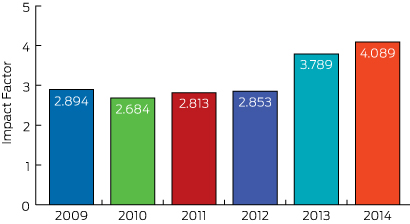

Whether any of us like it or not, our performance in medicine is being increasingly measured and critiqued, and it’s no different for medical journals. Clinicians and academics want to publish in the best medical journals and one metric applied universally is the impact factor, calculated by counting the mean number of citations received per article published during the previous 2 years. In the best journals, editors arguably “live and die” by the journal impact factor published each year. The impact factor is flawed (some argue fatally so) and is not used by the National Health and Medical Research Council; but it can’t be ignored either!1,2 In 2015, the MJA, your national journal, ranks in the top 20 general medical journals worldwide and has a highly respectable impact factor of 4.089 (Box, previous page). I am pleased to say that the impact factor of the MJA has risen and I anticipate over the coming years that it will continue to rise (as will other metrics of excellence) as we further increase the quality and reach of what we publish.

We welcome your best work being submitted for consideration. Our acceptance rate is currently falling (as marks all of the best medical journals) but I can pledge that your medical articles will be expertly peer reviewed and edited before publication. The editorial team will do its utmost to ensure it makes the best possible decisions, and we will work hard with authors to help them publish polished, excellent contributions.

Finally I would like to acknowledge and thank Professor Charles Guest in his capacity as Interim Editor-in-Chief for his stewardship of the Journal in the second half of 2015. He has been instrumental in supporting our editors and maintaining the continuity and the quality of the Journal.

Thank you for reading the MJA. You can expect that the Journal will be further increasing its scientific reputation and international presence over the next few years, and I hope you will be part of it if you have a contribution you wish to make. We welcome suggestions and feedback so we can further improve the Journal on your behalf. I am committed to strengthening your clinical practice through its pages and look forward to our journey together.

more_vert

more_vert