Anaemia affects roughly a third of the world’s population; half the cases are due to iron deficiency. It is a major and global public health problem that affects maternal and child mortality, physical performance, and referral to health-care professionals. Children aged 0–5 years, women of childbearing age, and pregnant women are particularly at risk. Several chronic diseases are frequently associated with iron deficiency anaemia—notably chronic kidney disease, chronic heart failure, cancer, and inflammatory bowel disease.

Preference: Infectious Diseases and Parasitology

434

Necrotising myositis presenting as multiple limb myalgia

Clinical record

A previously healthy 40-year-old man was referred by his general practitioner to our hospital after a short prodromal period of a sore throat and rapidly deteriorating constitutional symptoms. Most pertinent to his diagnosis was the development of non-traumatic, localised, right calf pain 48 hours before admission that progressed to an inability to bear weight by the time of hospital presentation. On initial physical examination, he had a temperature of 37.8°C, diffuse muscle tenderness in all four limbs and an exquisitely hyperalgesic localised area on the right mid-calf. Examination of his throat showed a diffuse pharyngitis. There was no rash or arthritis, and his cardiovascular, respiratory and gastrointestinal systems were all unremarkable at admission.

A blood sample and throat swab were taken and, after an initial blood and microbiological culture work-up, empirical treatment with intravenous flucloxacillin and vancomycin was commenced. Early pathology test results showed a creatine kinase (CK) level of 380 U/L (reference interval [RI], < 171 U/L), serum creatinine level of 158 μmol/L (RI, 55–105 μmol/L), white cell count of 3.1 × 109/L (RI, 4.0–11.0 × 109/L) with increased band forms, and deranged liver function test results, with a bilirubin level of 60 μmol/L (RI, < 20 μmol/L) and alanine transaminase level of 242 U/L (RI, 0–45 U/L).

Over the next 24 hours, the patient’s condition deteriorated, prompting consultation with an infectious diseases specialist. This resulted in a change of antibiotic therapy to ceftriaxone to broaden the coverage of respiratory pathogens, given his acute pharyngitis, and clindamycin to restrict any potential toxin production. By the evening of the second hospital day, the patient was referred to the intensive care unit (ICU) with evolving multiple organ failure. He was now febrile to a temperature of 40°C, with evolving septic shock, pulmonary infiltrates, worsening acute kidney injury (serum creatinine level, 201 μmol/L, and oliguria) and mild delirium. His right calf remained a focal point of concern, with an accompanying tenfold rise in CK level to 3656 U/L.

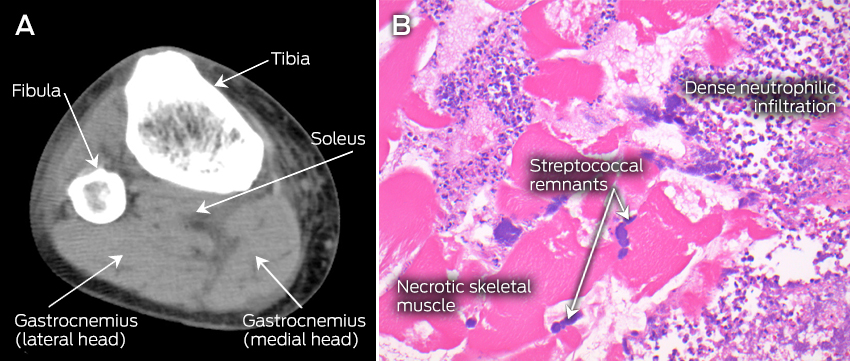

The patient’s condition further deteriorated during his first night in the ICU, necessitating aggressive fluid resuscitation, vasopressor support and haemodialysis. By the morning of the third day in hospital, 12 hours after ICU admission, an isolated, small, tender area of discolouration was noted over the distal posteromedial aspect of the right leg, with no other clinically apparent lesions, but persisting myalgia in all four limbs. This, in conjunction with the confirmation of gram-positive cocci grown from the admission blood and throat swab cultures, prompted the initial consideration of necrotising fasciitis. Subsequent imaging of the lower limbs with ultrasound and non-contrast computed tomography (CT) scans excluded venous thrombosis and fascial thickening, but both tests showed subtle swelling of the calf muscles, suggesting myositis (Figure, A). An urgent plastic surgery consultation mandated surgical exploration of the right calf, and the diagnosis of necrotising myositis (NM) (Figure, B) was subsequently obtained.

Due to the ongoing requirement for frequent soft tissue debridement, the patient was ventilated and transferred to the nearest quaternary hospital. Here, he underwent further imaging of all four limbs and successive debridement of his right leg and both arms for NM on Days 4, 5, 7, 9 and 18 of admission. After receiving confirmation of susceptibility, the ceftriaxone was changed to benzylpenicillin, while clindamycin was retained and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) commenced. Microbiological serotyping confirmed Streptococcus pyogenes with type emm 89.0 strain; exotoxin assays were not conducted. The patient’s total ICU stay lasted 17 days, with liberation from haemodialysis after 7 days and the ventilator after 9 days, resolution of his multiple organ failure, and all four limbs preserved without amputation. After 33 days in hospital, he was discharged to a rehabilitation centre.

Necrotising myositis is a rare but potentially fatal form of infection, predominantly characterised by muscle necrosis capable of rapidly progressing to multiple organ failure in healthy young adults. Published literature attributes group A streptococcus as the most commonly implicated pathogen, but NM has also been associated with groups C and G streptococci, Bacteroides subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus and Peptostreptococcus.1,2

Our case highlights three important clinical lessons. First, NM typically involves a single limb or area. Multiple limb involvement in the initial presentation has only been reported in two previous cases.3,4 Second, despite the widespread limb involvement in our patient, skin discolouration was a subtle, late sign. It presented in only one limb 72 hours after symptom onset, at a stage when the toxic shock syndrome was already apparent. Of 14 previously reported cases, only five describe skin discolouration and two describe local erythema.1,3–8 Third, and most crucially, NM, like necrotising fasciitis, remains a clinical diagnosis, with most investigations being indeterminate.

Increased serum CK level has previously been lauded as a potential early warning sign,4–6 but the initial CK result at our patient’s hospital admission (already more than 48 hours after the onset of symptoms) was only marginally raised (380 U/L). We found two other previously reported cases of NM where the CK level remained below 500 U/L at 48–72 hours after symptom onset.6,7 These findings suggest that excluding NM on the basis of small rises in serum CK level (< 500 U/L) is unreliable. Similarly, a reliance on imaging to provide a diagnosis can result in non-specific or negative findings, delaying a definitive surgical diagnosis and treatment.8 While modern imaging can be performed rapidly, the CT and ultrasound scan findings in our patient were subtle, non-specific and ultimately delayed surgery by 3–4 hours.

Once a diagnosis of NM is suspected, aggressive surgical debridement, appropriate antibiotic therapy and supportive care are mandated for survival. Early surgical intervention has reduced mortality from 100% to 37%,1 but with the consequence of significant long-term morbidity for many survivors. Aggressive group A streptococcal infections respond less well to penicillin and continue to be associated with high mortality and extensive morbidity, leading to the use of adjunctive therapies.9 In a recent observational Australian study of 84 patients with severe invasive group A streptococcal infection, the addition of clindamycin resulted in a significant reduction in mortality, which was further enhanced by the inclusion of IVIG.10 Clindamycin inhibits bacterial protein synthesis at the level of the 50S ribosome, resulting in decreased exotoxin production and increased microbial opsonisation and phagocytosis, while IVIG increases the ability of plasma to neutralise superantigens.9,10 Finally, conclusive evidence is lacking for the use of hyperbaric oxygenation, aimed at reducing hypoxic leucocyte dysfunction, and it was not used for this patient.

Lessons from practice

-

Necrotising myositis is a rare but potentially fatal condition. It is a diagnostic conundrum, often presenting as systemic toxicity and widespread myalgia without focal features.

-

Improved survival is underpinned by early clinical diagnosis, appropriate antibiotic therapy including clindamycin to reduce exotoxin load, and urgent surgical referral. Adjunctive therapies such as intravenous immunoglobulin and hyperbaric oxygenation should be considered based on individual circumstances.

-

Previously suggested diagnostic investigations such as serum creatine kinase levels, ultrasound and computed tomography scans are unreliable, mandating a high index of clinical suspicion to make a diagnosis.

Figure

A: Computed tomography scan (transverse plane) of the right leg, showing subtle hypointense and mildly expanded gastrocnemius and soleus muscles with intact fascia, suggestive of myositis. B: Haematoxylin and eosin stained paraffin section of the right gastrocnemius muscle, showing necrotic skeletal muscle, inflammatory infiltrate with disintegrating neutrophils and colonies of streptococcal bacteria.

News briefs

New evidence suggests Zika virus can cross placental barrier

Zika virus has been detected in the amniotic fluid of two pregnant women whose fetuses had been diagnosed with microcephaly, according to a study published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases last month. The report suggests that Zika virus can cross the placental barrier, but does not prove that the virus causes microcephaly. “The number of reported cases of newborn babies with microcephaly in Brazil in 2015 has increased 20-fold compared with previous years. At the same time, Brazil has reported a high number of Zika virus infections, leading to speculation that the two may be linked. The two women presented with symptoms of Zika infection including fever, muscle pain and a rash during their first trimester. Ultrasounds taken at approximately 22 weeks of pregnancy confirmed the fetuses had microcephaly. Samples of amniotic fluid were taken at 28 weeks and analysed for potential infections. Both patients tested negative for dengue virus, chikungunya virus and other infections such as HIV, syphilis and herpes. Although the two women’s blood and urine samples tested negative for Zika virus, their amniotic fluid tested positive for Zika virus genome and Zika antibodies.”

Eighth retraction for former Baker IDI researcher

Anna Ahimastos, a former heart researcher with Baker IDI Heart and Diabetes Institute in Melbourne, has recorded her eighth retraction after faking patient records. “The [Baker IDI] investigation found fabricated patients records in some papers; in other papers, such as the newly retracted 2010 study in Atherosclerosis, the original data source could not be verified,” Retraction Watch reports. “The latest retraction — A role for plasma transforming growth factor-β and matrix metalloproteinases in aortic aneurysm surveillance in Marfan syndrome? — followed up on a previous clinical trial, examining how a blood pressure drug might help patients with a life-threatening genetic disorder. That previous trial — which also included 17 patients with Marfan syndrome treated with either placebo or perindopril — has been retracted from JAMA; the New England Journal of Medicine has also retracted a related letter.” A spokesperson for Baker IDI was quoted as saying: “In total, this brings the number of retractions arising from our investigations to eight and concludes the process of correcting the public record in relation to three studies with which the researcher was associated. We are not aware of Miss Ahimastos’ current whereabouts.”

Is dementia in decline? NEJM urges caution

A perspective published in the New England Journal of Medicine (doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1514434) warns that research in the same issue showing a 20% decrease in dementia incidence each decade from 1975 to the present should cause physicians and researchers to “think carefully”. “Faced with choices between equally defensible epidemiologic projections, physicians and researchers must think carefully about what stories they emphasise to patients and policymakers. The implications, especially for investment in long-term care facilities, are enormous. Our explanations of decline are equally important, since they guide investments in behavior change, medications, and other treatments. Optimism about dementia is more justified than ever before. Even if death and taxes remain inevitable, cancer, coronary artery disease (CAD), and dementia may not. But cautious optimism should not become complacency. If we can elucidate the changes that have contributed to these improvements, perhaps we can extend them. Today, the dramatic reductions in CAD-related mortality are under threat. The incipient improvements in dementia are presumably even more fragile. The burden of disease, ever malleable, can easily relapse.”

WHO releases “R&D Blueprint” in search for Zika vaccine

The World Health Organization (WHO) has set in motion a “rapid R&D response” to the Zika virus outbreak in Brazil, learning from its Ebola virus experience in West Africa. Writing on WHO’s website, Dr Marie-Paule Kieny, Assistant Director-General, Health Systems and Innovation, said “our relatively poor knowledge of the Zika virus presents a series of challenges for research and development”. “Numerous groups are looking at the feasibility of initiating animal or human testing, particularly for vaccines and diagnostics. For vaccines, the landscape is evolving swiftly, and numbers change daily. About 15 companies and research groups have been identified so far. Two vaccine candidates seem to be at a more advanced stage: a DNA vaccine from the US and an inactivated product from India. Although the landscape is encouraging, it will be at least 18 months before vaccines could be tested in large-scale trials. For diagnostics, 10 biotech companies have been identified so far that can provide nucleic acid or serological tests. Ebola taught the global R&D community many valuable lessons, and proved that when we work together, we can develop new medical products much faster than we thought possible. Although we know even less about Zika than we did about Ebola, we are learning more every day and are much better prepared to advance much-needed research to blunt the threat of Zika.”

‘Beer goggles’ a myth, says new research

Researchers from the University of Bristol in the UK have found that there is no association between the amount of alcohol consumed and perception of attractiveness, according to their study published in Alcohol and Alcoholism. The authors ran an “observational study conducted simultaneously across three public houses in Bristol”. “Excessive alcohol consumption is linked to unsafe sexual behaviours. This relationship may, at least in part, be mediated by increased perceived attractiveness of others after alcohol consumption, a relationship colloquially termed the ‘beer-goggles effect’,” the authors wrote. “Participants were required to rate the attractiveness of male and female face stimuli and landscape stimuli administered via an Android tablet computer application, after which their expired breath alcohol concentration was measured. Linear regression revealed no clear evidence for relationships between alcohol consumption and either overall perception of attractiveness for stimuli, for faces specifically, or for opposite-sex faces. The naturalistic research methodology was feasible, with high levels of participant engagement and enjoyment.”

[Correspondence] Economists, universal health coverage, and non-communicable diseases

We welcome the declaration in support of universal health coverage (UHC) by Lawrence Summers1 on behalf of 267 economists from 44 countries. We are astounded, however, by the complete absence of tackling non-communicable diseases (NCDs) from this call for action. This is especially surprising given the strong focus on NCDs in the Lancet Commission on Investing in Health, chaired by Summers,2 and the cost-effectiveness of many NCD interventions that can be adapted and simplified for inclusion in suitable packages.

[Correspondence] The Hajj Health Requirements: time for a serious review?

More than 2 million Muslim pilgrims from around 180 countries congregate annually in Saudi Arabia for the Hajj religious mass gathering. This event can potentially affect global health security because of the possibility that infectious agents will spread beyond Saudi Arabia via returning pilgrims. The Hajj Health Requirements are a set of health conditions for individuals intending to do the Hajj pilgrimage aimed at preventing communicable diseases.1 Historically, these illnesses were the largest cause of morbidity and mortality during the event, but non-communicable diseases are now the major burden.

5 things you need to know about the new Hepatitis C medicines on the PBS

Four new hepatitis C medications have been added to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme from 1st March 2016, providing new hope for sufferers.

Helen Tyrrell, chief executive officer of Hepatitis Australia, told MJA InSight that new listing meant “exciting times” ahead.

“There is a real opportunity here,” she said. “If we can get the treatment out there, get GPs engaged, there is a real chance of eliminating hepatitis C [as a public health threat] within 10 to 15 years.”

Here are 5 facts you need to know about the new listing.

1. What drugs are listed and how much will they be?

The medicines scheduled for listing on the PBS are daclatasvir (Daklinza®); ledipasvir with sofosbuvir (Harvoni® ); sofosbuvir (Sovaldi® ) and ribavirin (Ibavyr® ). The PBS listing for peginterferon alfa-2a (&) ribavirin (Pegasys RBV® ) will also be amended to allow its use in combination with sofosbuvir.

According to the PBS, these new medicines have a cure rate of greater than 90%. Treatment is also ‘shorter in duration, less complex and much better tolerated that traditional treatments’.

Under the PBS, the treatments will cost $38.30 for general patients and $6.20 for concessional patients.

Related: Jason Grebely & Gregory Dore: Hep C crossroads

2. Who can prescribe them?

To qualify for the PBS subsidy, gastroenterologists, hepatologists, or infectious disease physicians who are experienced in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C will be eligible to prescribe the new medication. General practitioners will still be able to prescribe under the PBS as long as it is done in consultation with a gastroenterologist, hepatologist, or infectious disease physician experienced in the treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection. According to the PBS, this means that the ‘GP must consult with one of the specified specialists by phone, mail, email or videoconference in order to meet the prescriber eligibility requirements.’

Dr Fran Bramwell, a Melbourne GP and the RACGP’s representative on an expert panel which prepared a consensus statement on the soon-to-be-published Australian Recommendations for the Management of HCV Infection admitted to MJA InSight that it will be an adjustment for GPs.

“For high caseload GPs it will be cumbersome in the beginning,” she said. “We will have to see how things develop in the next few months, but GPs have demonstrated time and time again that they are responsible about what medications they prescribe.”

She said she is hopeful that the requirements could be amended in the following months so S 100 prescribers would be able to prescribe the Hepatitis C drugs without a specialist’s approval.

3. What information do doctors need to provide in order to prescribe this drug?

Prescribers will need to provide information about the heptatitis C virus genotype and the patients cirrhotic status (non-cirrhotic or cirrhotic).

The following must be documented in the patient’s records:

- evidence of chronic hepatitis C infection (repeatedly antibody to hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV) positive and hepatitis C virus ribonucleic acid (HCV RNA) positive);

- evidence of the hepatitis C virus genotype.

Related: Hep C cure comes with $3 billion price tag

4. Can my patients get a repeat?

The current PBS restrictions don’t prohibit patients receiving repeats or a different course of treatment however it is not supported by current evidence. The Department will review the use of the medicines in the future to ensure value for money for the taxpayer.

5. Where can I get more training/information?

The Department of Health’s have released a Frequently Asked Questions list for Healthcare providers.

The Australasian Society of HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexual Health Medicine (ASHM) runs 2-day s 100 prescriber accreditation courses as well as 1-day hepatitis C new treatment courses.

Latest news:

Zika virus may cause other birth defects, stillbirth: study

A case study of a Brazilian woman and her baby has pointed to the possibility that the Zika virus may cause birth defects other than microcephaly.

PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases published the case study about a 20-year-old woman whose stillborn baby had signs of severe tissue swelling as well as central nervous system defects that caused the central hemispheres of the brain to be absent.

Albert Ko, M.D. of the Yale School of Public Health and Dr. Antônio Raimundo de Almeida at the Hospital Geral Roberto Santos in Salvador, Brazil led the research, saying it provides evidence that Zika infection may also be linked to hydrops fetalis, hydranencephaly and fetal demise.

Related: Qld to ramp up Zika testing after 8th case

The woman experienced a normal first trimester, however doctors started seeing abnormalities during the 18th week of pregnancy when the foetus’ weight was well below what it should have been.

In the 30th week, the foetus showed a range of birth defects including “severe microcephaly, hydranencephaly, intracranial calcifications and destructive lesions of posterior fossa, in addition to hydrothorax, ascites and subcutaneous edema”. Labour was induced at 32 weeks due to foetal demise.

Testing confirmed the presence of Zika virus in the foetus however the woman didn’t report any of the symptoms commonly associated with Zika prior to or during her pregnancy.

The researchers admit that it’s not possible to understand the overall risk for women exposed to the virus during pregnancy from just one single case.

“Given the recent spread of the virus, systematic investigation of spontaneous abortions and stillbirths may be warranted to evaluate the risk that ZIKV infection imparts on these outcomes,” they wrote.

Latest news:

Patchy vaccination coverage leaves some at risk

Vaccination rates in some areas are so low that they are vulnerable to the spread of potentially dangerous diseases such as measles and whopping cough.

A report detailing child vaccination rates nationwide has found that although almost 91 per cent of children were fully vaccinated in 2014-15, in more than 100 postcodes less than 85 per cent were fully immunised, including just 73.3 per cent in the Brunswick Heads area on the New South Wales north coast.

The National Health Performance Authority report indicates that the country has a considerable way to go to achieve the target set by the Commonwealth, State and Territory chief health and medical officers for 95 per cent of all children to be fully vaccinated, though there were some encouraging signs of progress.

The NHPA found immunisation rates among one-year-old Indigenous children increased significantly in 14 per cent of geographical areas, and there was a big 8 percentage point jump in the rate outback South Australia.

The report also revealed improvements in Surfer’s Paradise, and the eastern suburbs of Sydney.

The findings were released against the backdrop of concerted efforts nationwide to boost immunisation rates, most notably through the Federal Government’s No Jab, No Pay laws, which deny family tax supplements and childcare benefits and rebates to parents who refuse to have their children vaccinated.

There have been anecdotal reports of surge in vaccinations before the commencement of the school year as the new rules loomed, but public health expert Julie Leask warned the causes of low vaccination rates were complex, and it was too early to assess the effectiveness of the No Jab, No Pay laws.

In her Human Factors blog (https://julieleask.wordpress.com/), Ms Leask, a social scientist at Sydney University’s School of Public Health, said a significant percentage of the 84,571 children reported as not fully vaccinated were in fact up-to-date but there were errors in recording their status on the Australian Childhood Immunisation Register.

In other instances, parents were unaware of vaccination requirements, or encountered problems in arranging for the immunisation of their children.

Ms Leask said that without further research, it was impossible to know how many children were being denied immunisation because their parents objected to it.

She said there were encouraging accounts of some parents who were previously objectors arranging for their children to be vaccinated – including some who were “angry and resentful, feeling coerced into making the decision because they cannot afford to miss the payments”.

But Ms Leask aired concerns about the implementation of the No Jab, No Pay laws.

She said Primary Health Networks and providers including GPs, nurses and Aboriginal health workers were being forced to work “very hard to implement a complex policy in a very short timeframe,” with often inadequate resources.

Providers were in many cases being overwhelmed by demand and had not been provided with additional assistance, and were being denied access to the ACIR and so could not update patient details.

The importance of high rates of vaccination have been underlined by warnings that the world remains “significantly off-track” targets to eliminate measles, and that communities with immunisation rates below 90 per cent were at risk of fast-spreading outbreaks.

The Gavi Vaccine Alliance said that although the number of deaths from malaria worldwide had fallen substantially in the past decade, the disease still claimed 114,900 lives in 2014 – most of them children younger than five years.

Gavi said it had developed a new approach to support periodic, data-driven measles and rubella campaigns in addition to action to tackle outbreaks.

“Measles is a key indicator of the strength of a country’s immunisation systems and, all too often, it ends up being the canary in the coalmine,” Gavi Chief Executive Dr Seth Berkley said. “Where we see measles outbreaks, we can be almost certain that coverage of other vaccines is also low.”

Adrian Rollins

Hand hygiene initiative successful but not economical

A study has found the Australian National Hand Hygiene initiative run in hospitals was a successful program, protecting many hospital patients from dangerous bugs.

However at $2.9 million a year, it was found to be an expensive program to run.

The NHMRC-funded evaluation of the program that ran in 50 hospitals across Australian from 2009 – 2012 was published in PLOS One.

The aim of the program was to reduce healthcare associated Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia and one of the key messages from the initiative was the ‘five moments of hand-hygiene’ which highlighted critical times for health workers to wash their hands to control infection.

Related: Doctors drag chain on hand hygiene

Professor Nicholas Graves from QUT’s Institute of Health and Biomedical Innovation (IHBI) said the program didn’t stack up against other health care programmes that might need to be funded.

“Health economists use the concept of ‘life years gained’ to assess the health benefits of competing programs,” Professor Graves said.

“We look for programs that provide extra years of life at the lowest cost, and we should pick the bargains first if we want to get the biggest bang for our health buck.

Related: Doctors reject hand hygiene reminders

“The extra $2.9 million bought us only 96 years of life for the whole country, this is about $29,700 per life year gained.”

The value for money varied across the states. In Queensland, the program got better value per month however in Western Australia the infection risk was very low and there were no new cases prevented, meaning almost $600,000 got spent for nothing.

As a comparison, Professor Graves said other research that looked at interventions for prevention, screening, diagnosis, and treatment had shown life years could be gained for $18,720, and a large number of programs cost under $10,000 per life year.

Latest news:

A 3-year study of high-cost users of health care [Research]

Background:

Characterizing high-cost users of health care resources is essential for the development of appropriate interventions to improve the management of these patients. We sought to determine the concentration of health care spending, characterize demographic characteristics and clinical diagnoses of high-cost users and examine the consistency of their health care consumption over time.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective analysis of all residents of Ontario, Canada, who were eligible for publicly funded health care between 2009 and 2011. We estimated the total attributable government health care spending for every individual in all health care sectors.

Results:

More than $30 billion in annual health expenditures, representing 75% of total government health care spending, was attributed to individual costs. One-third of high-cost users (individuals with the highest 5% of costs) in 2009 remained in this category in the subsequent 2 years. Most spending among high-cost users was for institutional care, in contrast to lower-cost users, among whom spending was predominantly for ambulatory care services. Costs were far more concentrated among children than among older adults. The most common reasons for hospital admissions among high-cost users were chronic diseases, infections, acute events and palliative care.

Interpretation:

Although high health care costs were concentrated in a small minority of the population, these related to a diverse set of patient health care needs and were incurred in a wide array of health care settings. Improving the sustainability of the health care system through better management of high-cost users will require different tactics for different high-cost populations.

more_vert

more_vert