Hepatitis E virus (HEV) outbreaks have not previously been reported in Australia. HEV infection mostly occurs in developing countries where transmission occurs via the faecal–oral route and contaminated water, causing large outbreaks.1 HEV genotypes 1 and 2 predominate in these settings.2 Like other forms of acute viral hepatitis, symptoms of HEV include jaundice, malaise, anorexia, fever and abdominal pain.1 The incubation period is 15–64 days.3

Recently, HEV transmission has been reported in developed countries, where infection has occurred via HEV-contaminated food. Consumption of pork products, deer meat, wild boar and shellfish has been implicated, with HEV genotypes 3 and 4 being detected in infected persons.2,4–8

Pigs, in particular, may play a role in human HEV transmission.9 An increased risk of HEV infection associated with the consumption of processed pork products was found by a recent case–control study in the United Kingdom.10 Human and swine HEV strains exhibit a high degree of sequence homology.5,11,12 Occupational exposure may be important, as seroprevalence rates have been found to be higher in pig veterinarians, pig farmers and abattoir workers than in healthy controls.13–15

In Australia, HEV infection is notifiable to state and territory public health authorities. Common laboratory practice has been to test for HEV infection only in those with a history of overseas travel. Each year, 30 to 40 infections in returned travellers from HEV-endemic regions are reported, including 10 to 20 in New South Wales.16

In October and November 2013, NSW Health was notified of two apparently unrelated cases of HEV infection within 2 weeks. Each person had been tested because of preceding overseas travel, albeit outside the incubation period for HEV infection. The HEV RNA isolated from these two people was genetically identical. A family member of one of the patients presented with symptoms of HEV infection 4 weeks later.

In May 2014, we received a further HEV notification, an infection in a man who reported that a work colleague from another state was also infected with HEV. Neither had travelled overseas during their incubation periods. The only common exposure was a meal shared with seven other colleagues at restaurant X, and the index patient reported that three of the seven were symptomatic. All co-diners were interviewed and tested, and HEV RNA was detected in the three symptomatic co-diners. HEV RNA from the five infected persons was genotypically identical, and also with that from two of the three 2013 cases. During routine interview of the three HEV-infected people in 2013, one had reported eating at restaurant X during their incubation period, while another had not. During a follow-up interview in 2014, the third person was specifically asked about this exposure, and reported eating at restaurant X during their incubation period.

In this article we report our epidemiological investigation of the source and extent of the apparent outbreak.

Methods

Epidemiological investigation

Case definition

We defined a case of HEV infection as a person who resided in NSW with laboratory-confirmed HEV, verified by IgG seroconversion or detection of HEV-specific IgM or HEV RNA, with an onset date (or specimen collection date, if onset date was unknown) between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2014.

Case finding and data collected

We identified cases in three ways:

-

Routine notification: As part of routine surveillance, pathology laboratories are required by the NSW Public Health Act 2010 to notify public health units of HEV infections. Surveillance specialists interview infected persons, using a standardised questionnaire. The information collected includes symptoms of illness, occupation, travel history, and water and food sources (including restaurants) during the incubation period. When an infected person had eaten at restaurant X, the interviewer asked about details of the food consumed there.

-

Testing of co-diners from restaurant X: Co-diners of infected persons from restaurant X were interviewed and tested for HEV.

-

Retrospective serological surveys: We tested all sera stored at a large public laboratory, with specimen dates between 1 September 2013 and 31 May 2014, for which HEV testing had been requested but not conducted because laboratory protocols excluded testing in the absence of a relevant travel history (survey 1). We also tested sera stored at a major NSW private pathology laboratory, with specimen dates between 1 January and 31 May 2014, where the alanine transaminase (ALT) level was > 200 IU/L and hepatitis A, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, Epstein–Barr virus and cytomegalovirus infections had been excluded, but HEV testing was not performed (survey 2).

Laboratory investigation

Serology

Anti-HEV IgM and IgG were detected using HEV IgM ELISA 3.0 and HEV ELISA kits respectively (MP Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reactive sera were re-tested and reported as positive if again reactive.

Viral detection and sequencing

Serum samples from confirmed cases were analysed at the Victorian Infectious Diseases Reference Laboratory. HEV RNA was extracted from serum using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini kit (QIAGEN) and initially tested using a commercial HEV RNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay (RealStar HEV RT-PCR). Samples containing HEV RNA were re-assayed by an in-house PCR assay using primers designed to amplify a portion of open reading frame (ORF) 2. The resulting PCR product was directly sequenced with internal primers. Sequences were aligned and compared with sequences in GenBank.

Environmental investigation

Investigation and food testing linked to restaurant X

Food handling and safety procedures at restaurant X were reviewed on 15 May 2014. Preparation of pork liver pâté was observed in detail. The internal temperature of sliced pork livers was measured by inserting a thermometer into the thickest part after 3 and 4 minutes’ cooking.

Three lots of chorizo sausage, three batches of cooked pork liver pâté, one sample of raw pork shoulder and raw pork jowl, one batch of cooked pork liver and eight raw pork liver samples from restaurant X were collected on 15 and 22 May 2014.

After extraction and purification using the MagMax Total RNA Isolation Kit (Life Technologies), samples were tested for HEV by Advanced Analytical Australia with real-time PCR, using Hepatitis E@ceeram Tools (Ceeram).

Pork products were traced back to their source by identifying the supplier from restaurant records; through the supplier we identified the farms from which the products originated.

Testing of pork liver sausages linked with an HEV case not linked to restaurant X

One of the infected persons without a link to restaurant X reported eating pork liver sausages during their incubation period, and had stored frozen uncooked sausages in a domestic freezer. Multiple samples were collected from several sausages and analysed for HEV at the Virology Laboratory of the Elizabeth Macarthur Agriculture Institute. Nucleic acid was purified and tested by real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR)17 using previously published primers and probe sequences.18

Data analysis

Responses to questionnaires administered to interviewees were transferred to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for analysis. Responses about food histories were analysed, and relative risks and confidence intervals calculated using Epi Info 7 (Centers for Disease Control). The Fisher exact test (two-tailed) was used to test for differences between groups; P < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Ethics approval

These studies were conducted as part of a public health investigation under the NSW Public Health Act 2010 and review by a human research ethics committee was not required.

Results

Epidemiological investigation

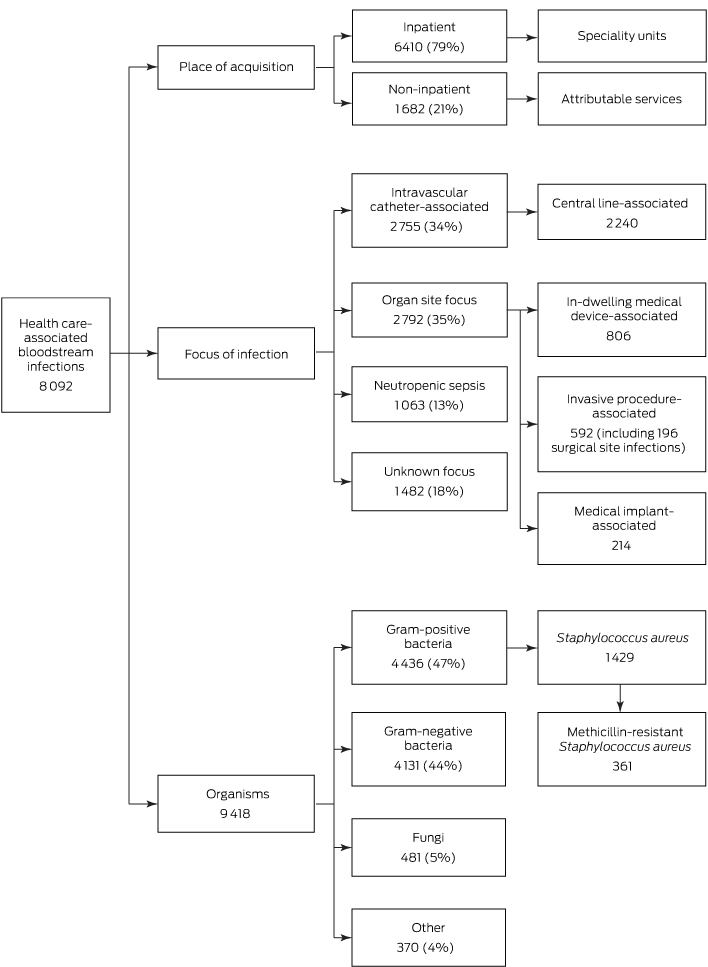

Notified HEV cases

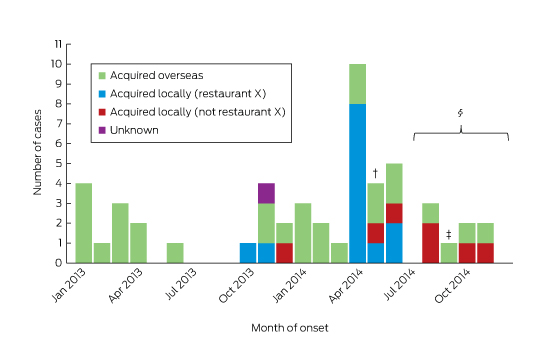

Between January 2013 and December 2014, 55 cases of HEV infection were notified (Box 1). The median age of the patients was 45 years (range, 4–77 years), 36 (65%) were male, and all but one (98%) lived in metropolitan Sydney. Twenty-four (44%) required hospitalisation, with a reported median length of stay (where known) of 7 days (range, 1–67 days). Three people (identified as co-diners of notified patients) were asymptomatic, and details about symptoms were unknown in one case. ALT levels were elevated in 33 of the 37 patients for whom they were recorded, with a median value of 1058 IU/L (range, 26–4868 IU/L; reference interval, 10–40 IU/L). None were pregnant.

Of the 55 patients, 30 (55%) reported a history of overseas travel during their incubation periods: to South Asia (17), East Asia (six), South-East Asia (two), Africa (two), Europe (two), or the Middle East (one). One patient could not be contacted; the remaining 24 (44%) did not report overseas travel.

Restaurant X outbreak

Restaurant X mainly served dishes suitable for sharing by a group. The menu included more than 28 meat, seafood and vegetarian options. Seventeen cases of HEV infection in nine separate groups who dined between October 2013 and May 2014 were linked to restaurant X. Of these 17, seven were identified by routine surveillance, eight by testing co-diners, and two by the retrospective serosurveys. Two people refused further interview; food histories were collected from the remaining 15 infected persons and from seven dining companions who tested HEV-negative by serology.

The demographic data for the diners is summarised in Box 2; the food items most commonly consumed are listed in Box 3. The highest attack rates were in those who consumed pork liver pâté, pork chorizo or roast pork. All 15 patients who provided a food history reported consuming pork liver pâté, compared with four of the seven uninfected co-diners (P < 0.05).

Locally acquired cases not linked to restaurant X

During interviews, the seven infected persons not linked to restaurant X reported eating a number of pork products during their incubation periods, including supermarket ham, prosciutto, pork liver, homemade pork liver sausage, pork chops and pork belly.

Retrospective serological surveys

Of 136 serosurvey samples (31 in survey 1, 105 in survey 2), nine (6.6%) were IgG-positive, four (2.9%) were IgM-positive, and four (2.9%) were both IgM- and IgG-positive for HEV. Of the eight people who were IgM-positive, HEV RNA was detected in four; sequencing confirmed infection with genotype 3. Two of these four people reported eating at restaurant X but not overseas travel, one reported travel to an HEV-endemic country, and one could not be contacted.

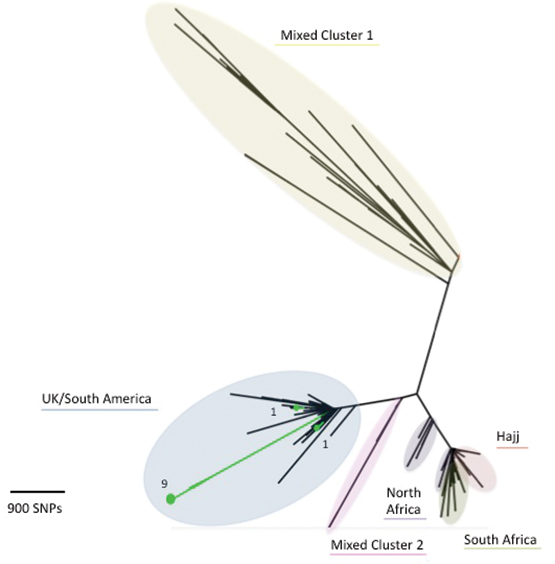

Laboratory investigation

HEV RNA was detected in samples from ten of the 17 restaurant X cases; of the others, five with mild or no symptoms were PCR-negative, one was PCR-negative but showed seroconversion, and a sample was unavailable in one case. Sequencing of the ORF2 region was successful for all ten samples, and the HEV isolate was classified as genotype 3. There was at least 99% between-sample sequence homology in the targeted portion of ORF2 among restaurant X isolates.

HEV RNA was also detected in six of the seven locally acquired infections not linked to restaurant X (the specimen supplied by one person was insufficient for testing): five were genotype 3, and one sample was insufficient for genotyping. The viral sequence of these samples was about 90% homologous with samples from the restaurant-linked cases.

Environmental investigation

Investigation of restaurant X

Restaurant X was found to be well managed; no breaches in food safety or handling were identified. Staff were trained in handwashing and general food safety, including understanding cross-contamination and temperature control. During the observed cooking process, the internal temperature of the pork livers reached 51°C at 3 minutes, and between 82°C and 97°C at 4 minutes.

The livers used for pâté preparation were traced to a single farm. The pork shoulder, jowl and chorizo products were all sourced from different suppliers to the pork livers. HEV was not detected in any of the food samples obtained from the restaurant.

Investigation of pork products of locally acquired cases not linked to restaurant X

Pork products eaten by the seven infected persons not linked to restaurant X were bought from four different butchers and three different supermarkets. Pork livers from two of these butcheries could be traced back to two abattoirs supplied by several farms; further tracing was not undertaken. Pork liver sausages still held by one patient were found to contain very low levels of HEV RNA; the levels were too low for sequencing.

Public health interventions

NSW Health convened an expert panel involving public health, clinical, laboratory, agricultural and industry experts to assess the risks and to guide the investigation. On 15 May 2014, restaurant X was informed about its possible link with a number of cases of HEV infection. The importance of thorough cooking of pork products, including of pork liver pâté, was stressed, and the restaurant voluntarily removed this item from its menu. No further cases of HEV infection were linked to restaurant X.

As part of case finding, NSW Health issued an alert to gastroenterologists and public and private pathology laboratories in May 2014. The information garnered was then used to inform general practitioners in an alert, issued in September 2014, which requested that they consider HEV infection in people with a compatible illness, regardless of overseas travel. A joint media release with the New South Wales Food Authority, also issued in September 2014, urged the public to cook pork products thoroughly and, in particular, to cook pork livers to 75°C at the thickest part for 2 minutes.19

Discussion

This is the first reported Australian outbreak of locally acquired HEV infection and one of the largest linked with a restaurant reported anywhere. Seventeen cases were linked to consuming pork liver pâté at restaurant X during a 9-month period, and seven cases were linked to eating pork products bought from four butchers and three supermarkets with at least two different suppliers.

Retrospective serological testing identified a further eight previously undiagnosed cases of HEV infection (anti-HEV IgM). In two of these cases, HEV RNA was detected in people who reported no overseas travel but who had dined at restaurant X during their incubation periods. A further six cases were notified after the restaurant outbreak, probably as a result of increased vigilance and testing by clinicians. Data from a large public health laboratory confirmed this, with more than triple the number of HEV tests requested and carried out from July to December 2014 (after the laboratory began testing for HEV in people without a travel history) than during the same period in 2013 (unpublished data).

Active case finding among co-diners of restaurant cases detected locally acquired HEV infections that were either asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic, suggesting under-recognition and under-diagnosis of infection. A recent HEV serosurvey of blood donors by the Australian Blood Service identified past HEV infection in 14 of 194 blood donors without a history of overseas travel (7%).20 A case report in the Northern Territory21 and a study in Victoria22 each described single cases of HEV infection in which overseas travel was not implicated and no other risk factors were identified.

Common source outbreaks of HEV infection in high-income countries are rare. However, our investigation concurs with previous French,5 English10 and Japanese11 studies that have linked HEV infection with consumption of undercooked pork products. In these countries, locally acquired HEV infections predominate, and in 2013 accounted for 99% of all cases in France23 and almost 70% of cases in the UK.24

HEV is inactivated by heating to 71°C.19 Review of pork liver pâté preparation at restaurant X found that it was adequately cooked at the time of inspection, and testing available pork samples did not detect HEV RNA. It is nevertheless possible that, at the time of the restaurant infections (some weeks earlier), pork livers contaminated with HEV could have been undercooked at the thickest part before blending into pâté. This may explain the relatively low proportion of patrons infected with HEV at this popular restaurant. While we did not have access to leftover pâté samples from meals served to people infected at restaurant X that could be tested for HEV RNA, it was detected in pork liver sausages retained by one of the non-restaurant X patients.

Most fresh pork products in Australia are locally produced. The presence of HEV in Australian pigs was first noted in 1999 by a study that reported seropositivity rates of 17% in wild-caught pigs and more than 90% in commercial pigs by 16 weeks of age.25 To our knowledge, no further studies investigating the epidemiology of HEV in Australian pigs have been conducted. Despite the link between HEV outbreaks and pork products overseas, this discovery of HEV in Australian pigs did not translate into clinical practice, perhaps because HEV was not widely recognised as being endemic to Australian pigs, and because of a lack of awareness among Australian clinicians of the veterinary literature.

A limitation to this investigation was the time lag between some infected persons and co-diners being exposed, interviewed and tested for HEV, particularly co-diners of symptomatic persons from restaurant X. A lag in interviewing some infected persons and co-diners, coupled with the long incubation period of HEV (15–64 days), may have led to a recall bias in responses to the questionnaires and providing food histories. The limited sample size made it difficult to achieve statistically significant results. However, our findings are biologically plausible, and important associations could be deduced.

This study adds to our current understanding of the potential for HEV to be a food-borne illness in developed countries. Clinicians should request HEV testing in patients with acute hepatitis, irrespective of travel history, particularly where no aetiology has been determined. Laboratories should test for HEV where indicated to prevent under-recognition of infection. Health departments must be aware of the possibility of underestimating the prevalence of hepatitis E when using surveillance data. Pork products, particularly pork livers, should be cooked until they reach 75°C at the thickest part for 2 minutes.

Increased awareness, ongoing research and collaboration between primary industries, animal and human health authorities should help detect and prevent this and other emerging infectious diseases in Australia.

Box 1 –

Notifications of hepatitis E virus infections in New South Wales with onset dates between January 2013 and December 2014, by likely source of acquisition*

Box 2 –

Characteristics of infected diners and healthy co-diners at restaurant X, October 2013 – May 2014

|

|

Infected persons (cases)

|

Healthy co-diners

|

|

|

Number

|

17

|

7

|

|

Median age (range), years

|

48 (29–75)

|

45 (29–47)

|

|

≤ 39 years

|

5 (29%)

|

1 (14%)

|

|

40–59 years

|

6 (35%)

|

5 (71%)

|

|

≥ 60 years

|

6 (35%)

|

0

|

|

Unknown

|

0

|

1 (14%)

|

|

Sex: men

|

12 (71%)

|

4 (57%)

|

|

|

|

Box 3 –

Commonly reported food items consumed by infected diners and healthy co-diners at restaurant X between October 2013 and May 2014*

|

|

Number of people who ate the item

|

Number of people who did not eat the item

|

Risk ratio (95% CI)

|

P

|

|

Infected persons (cases)

|

Healthy co-diners

|

Attack rate (%)

|

Infected persons (cases)

|

Healthy co-diners

|

Attack rate (%)

|

|

|

Brussel sprouts

|

5

|

3

|

63%

|

8

|

4

|

67%

|

1 (0.5–1.8)

|

1.00

|

|

Calamari

|

3

|

2

|

60%

|

10

|

5

|

67%

|

1 (0.5–2.0)

|

1.00

|

|

Eggplant

|

7

|

5

|

58%

|

6

|

2

|

75%

|

0.8 (0.5–1.5)

|

0.66

|

|

Pork chorizo

|

7

|

2

|

78%

|

6

|

5

|

55%

|

1.5 (0.8–2.7)

|

0.36

|

|

Pork pâté

|

15

|

4

|

79%

|

0

|

3

|

0

|

Undefined

|

0.02

|

|

Roast pork

|

9

|

4

|

69%

|

4

|

3

|

57%

|

1.2 (0.6–2.6)

|

0.64

|

|

|

* Food histories were available for 15 of the 17 infected persons (13 were complete and two were incomplete) and for all seven well co-diners.

|

more_vert

more_vert