We need to fill evidence gaps and make clinical advances to reduce these diseases of disadvantage

Group A streptococcal (GAS) infections contribute to the excess burden of ill-health in Indigenous Australians, causing superficial infection, invasive disease, and the autoimmune sequelae of acute rheumatic fever (ARF) and acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (APSGN) (Box 1).1–6 GAS diseases declined in the broader Australian population during the 20th century, largely as a result of improved living conditions,7 but this is not the case in Indigenous Australians. GAS infections and their sequelae persist at unacceptably high rates in remote Australia, on par with or higher than those in low income settings internationally.8 GAS infections globally represent social disadvantage.5,8 Poverty, household overcrowding and distance from health care services are the main drivers.9

GAS impetigo

In remote Australian communities, impetigo, predominantly caused by GAS infection,2,10,11 affects a median of 45% of Indigenous children at any one time.3 This high prevalence is testament to the poor environmental conditions9 and household overcrowding in Indigenous communities.10,12 A high burden of circulating group A streptococcus strains13 and scabies are contributory factors.2 Further, skin infections are also “normalised”, which contributes to the burden as it is not seen as a significant problem — affecting both health care-seeking behaviour14 and the response by clinicians when patients present with other complaints.15 Despite being under-recognised, GAS impetigo is of public health importance. Untreated, it can lead to APSGN, with resultant acute cardiac morbidity from hypertension.1 Although acute case fatality rates are low (< 2%),1 APSGN in childhood increases the risk of chronic kidney disease later in life in Indigenous Australians.16

Precursor to rheumatic fever

ARF and subsequent rheumatic heart disease (RHD) are the most severe and life-threatening post-streptococcal diseases. Mortality rates from RHD in Indigenous Australians are the highest reported in the world.1 Traditionally, GAS pharyngitis has been considered the lone antecedent to ARF.17 Yet, in remote tropical Australia, GAS pharyngitis is uncommonly reported and GAS skin infections are hyper-endemic.12 Thus, impetigo, rather than pharyngitis, may be the driver. The findings of studies to clarify this dilemma have not been definitive.6,12 Recently, a New Zealand molecular epidemiological study using M-protein (emm) cluster typing found that 49% of ARF-associated GAS strains from isolates were emm pattern D (skin pattern) types.18 Further studies examining the causal link between GAS impetigo and RHD remain a priority if we are to make further progress towards the primary prevention of RHD.12

Current approaches to GAS infection control

Community and primary health programs

For decades, the focus in the Northern Territory has been on control of skin disease,10,11,19 although treatment for sore throat is also promoted.20 Community skin days and mass drug administration with permethrin11 have been successful, but their impact is not sustained. More recently, a better tolerated treatment regimen for impetigo was reported, with oral co-trimoxazole proven to be non-inferior to intramuscular penicillin;10 and mass drug administration with oral ivermectin shown to be an effective population approach to reducing scabies and impetigo.19 However, to date, no approach in Australia has achieved a sustained reduction in GAS impetigo. Overcrowding and population mobility are among the contributing factors and, more recently, the contribution of community members with crusted scabies as core transmitters of the scabies mite has been recognised.19 New approaches to management of crusted scabies in the NT include surveillance under public health legislation21 and coordinated case management.22 However, there remains a need to target the other contributing factors, particularly overcrowding, before sustained reductions can be achieved.

Policy and legislation

The only GAS diseases that have any jurisdiction-level policies or strategies are skin infections, APSGN, ARF and RHD. The NT has well established, evidence-based guidelines for community-level skin sore and scabies control, and an APSGN outbreak response.23 Other jurisdictions have adopted the APSGN guidelines when needed, but do not have legislation requiring notification of the disease. Through the national Rheumatic Fever Strategy, the Australian Government has funded the development and maintenance of register-based RHD control programs for monitoring the RHD burden and coordination of care, with a focus on secondary prophylaxis, in the NT, Queensland, Western Australia and South Australia, as well as the establishment of the National Coordination Unit.24,25 New South Wales established a statewide register in 2015.26 Centralised coordination of secondary prophylaxis, the only cost-effective method proven for RHD control,27 through electronic registers is advantageous for mobile populations if the systems are shared and accessible to all health service providers. Given that RHD has the highest differential mortality between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians of any preventable condition,28 continuation of Rheumatic Fever Strategy funding is essential if Australia is to achieve its Closing the Gap targets.

Areas for future focus to close the gap in GAS infection outcomes

Heightened surveillance

Currently, no GAS diseases are nationally notifiable,29 but a number are notifiable in different jurisdictions (Box 2). Passive surveillance via notifiable disease reporting would be the cheapest and least resource-intensive method30 for monitoring GAS diseases and their sequelae in remote Australia. ARF, scarlet fever, and puerperal fever were all nationally notifiable in Australia before 1990.31 All three are no longer nationally notifiable.

Surveillance programs for APSGN, ARF and invasive GAS infection in the NT or for RHD in WA, SA and NSW could be replicated elsewhere. In New Zealand, diseases that disproportionately affect Maori and Pacific Islander peoples are prioritised; national notification of ARF is legislated,32 and there are well resourced school screening programs for sore throat and skin infection.33 Legislating for notification of GAS diseases that disproportionately affect Australian Indigenous people would facilitate accurate disease monitoring and directed public health response, and provide advocacy tools for Indigenous health campaigners to demand action.

Primary prevention

Future approaches to comprehensive skin disease control programs will incorporate sustainable community-wide approaches, acceptable clinical treatments, appropriate contact management, evidence-based prevention and community control initiatives that are embedded in primary health care. Earlier skin disease control programs were effective initially,11 but were unsustainable due to the cost of using a largely external workforce. Combining streamlined treatment guidelines for impetigo, scabies and crusted scabies into training, health promotion and environmental health activities that are culturally secure will be critical. The role of skin disease control in ARF prevention is unclear, and requires a better understanding of the relationship between GAS impetigo and ARF. Monitoring the impact of sustained impetigo control measures on the incidence of ARF could be included in skin control programs to help us understand the potential role for impetigo control as a primary prevention strategy for ARF.

Research and development of new technologies

Development of a GAS vaccine

A vaccine against group A streptococcus would be a major advance in reducing the excess burden of GAS disease in Indigenous Australians, particularly in the current absence of a cost-effective primary prevention strategy for ARF. Several M-protein-based vaccines have progressed to human clinical trials,34 but none have yet moved beyond phase II trials. The need to cover multiple diverse strains and a standardised immunoassay for efficacy and immunogenicity monitoring are current barriers to vaccine development.35 The Coalition to Accelerate New Vaccines for group A Streptococcus (CANVAS), a joint initiative between the Australian and New Zealand governments, is tackling these barriers to advance GAS vaccine research.18

Long-acting penicillins for secondary prevention of ARF

The mainstay of secondary prevention of ARF remains intramuscular injections of benzathine penicillin every 28 days for a minimum of 10 years.36 A longer-acting, less painful way of administering penicillin would overcome some of the avoidance and acceptability issues with the current formulation.37 Key questions remain before a better alternative can be delivered, but progress is underway36 through studies examining the pharmacokinetics, patient preferences and the rationale behind the current formulation.

Primordial prevention

Although there is progress towards a potential vaccine and longer-acting antibiotics, these remain distant possibilities. Moreover, the large reductions in ARF and APSGN occurred in the wider population without these technologies.7 Indigenous people have not benefited from improvements in the social determinants of health that resulted in the virtual elimination of these conditions in the non-Indigenous population. As a contribution to improving socio-economic disadvantage, clinicians can provide health data to help quantify the disadvantage that exists. Capacity building through support and training of Indigenous clinicians is a necessity for providing accessible primary health care. Further capacity building will see Indigenous health practitioners become leaders in policy and research to facilitate Indigenous community control over health programs and funding. Empowering the community to vanquish the effects of more than two centuries of colonisation, racism and oppression should be at the forefront of policy development if we are to achieve equity in the social determinants of health and reduce the prevalence of diseases that represent disadvantage, including GAS infections and their sequelae.

Conclusions

Given the ongoing mortality and morbidity from chronic kidney and heart disease due to GAS infection in Indigenous Australians, we must address more effectively the treatment and prevention of the precursors, GAS impetigo and pharyngitis. An essential step in improved prevention and control is effective surveillance of GAS conditions. Quality surveillance data would quantify the disease burden at both a jurisdictional and national level, providing important information to guide resource allocation. Effective, sustainable skin disease control programs embedded within the activities of the existing workforce are another priority. New prevention initiatives in GAS vaccines and longer-acting penicillin therapy are progressing. However, despite these clinical advances, the top priority remains the need to improve the quality of housing and access to health care that continue to disadvantage remotely living Indigenous Australians — these are the underlying reasons for the inequity in GAS outcomes that continue today.

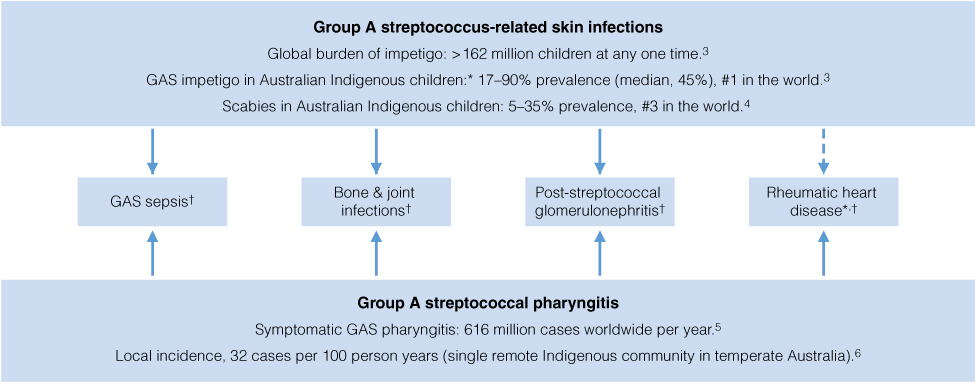

Box 1 –

The global and local burden of group A streptococcal (GAS) skin infections and pharyngitis and their sequelae

Box 2 –

Diseases caused by group A streptococcal infections that are notifiable under state and territory public health legislation in each state or territory of Australia29

|

Notifiable group A streptococcus-related condition

|

Australian state or territory

|

|

ACT

|

NSW

|

NT

|

Qld

|

SA

|

Tas

|

Vic

|

WA

|

|

|

Acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis

|

|

|

Yes

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Acute rheumatic fever

|

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

|

Yes

|

|

Invasive group A streptococcal infection

|

|

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rheumatic heart disease

|

|

Yes*

|

|

|

Yes

|

|

|

Yes

|

|

Scarlet fever

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes

|

|

|

ACT = Australian Capital Territory. NSW = New South Wales. NT = Northern Territory. Qld = Queensland. SA = South Australia. Tas = Tasmania. Vic = Victoria. WA = Western Australia. * Notifiable in people aged under 35 years.

|

more_vert

more_vert