Primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM) is a rare but fulminant disease leading to diffuse haemorrhagic necrotising meningoencephalitis, and has a very poor prognosis.1 Naegleria fowleri is the causative agent. At Townsville Hospital, our first confirmed case of PAM was an 18-month-old girl from a rural location in North Queensland who presented with fever, seizures and an altered level of consciousness.2 Organisms resembling Naegleria spp. were seen on microscopy of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Despite aggressive therapy with multiple antimicrobial agents, the patient died within 72 hours of presentation. An older sibling of the patient had presented with a similar syndrome several years earlier and had died of an undifferentiated meningitic illness. The sibling was retrospectively suspected to also have had PAM.2

Our second confirmed patient presented in early 2015. A previously well 12-month-old boy from a nearby West Queensland cattle-farming area had had a 36-hour history of fevers, rhinorrhoea and frequent emesis, which progressed to lethargy and irritability. Before arrival at the local rural hospital, he had a tonic–clonic seizure lasting 3–5 minutes. On arrival he appeared drowsy, had mottled skin, a blanching maculopapular rash, which may not necessarily have been related to PAM, and a central capillary refill of 3–4 seconds. He was treated with intravenous antibiotics for presumed bacterial meningitis. Given the remote location and clinical suspicion of elevated intracranial pressure, lumbar puncture was not performed. On arrival at Townsville Hospital, his Glasgow Coma Scale score was 8/15, he was increasingly febrile, and had an evolving maculopapular rash. Broad spectrum antimicrobial therapy was subsequently started for presumed meningoencephalitis. Within 18 hours of leaving home, he had no spontaneous respiratory effort, reduced tone, up-going plantar reflexes and fixed pupils.

Neuroimaging showed diffuse cerebral oedema with progressive dilation of the ventricular system on sequential studies. An external ventricular drain was placed because of clinical instability, and CSF microscopy showed motile trophozoites on a wet preparation and Giemsa stain, consistent with N. fowleri. The patient was commenced on intrathecal amphotericin, with no improvement in his clinical state. The organism seen in the CSF was confirmed after the patient’s death by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis as being N. fowleri. When reviewing the patient’s history, it was noted that, as in previous cases, he lived on a property that used untreated and unfiltered bore water domestically, to which he had multiple potential exposures, including via water play with hoses and bathing.

Literature review

We searched the PubMed database using the terms “Naegleri”, “fowleri” and “meningitis”. No time period was specified. The James Cook University eJournal database was searched for historical information.

We also searched the Queensland Health Communicable Diseases Branch and the Communicable Diseases Network Australia databases for Australian cases, but, as N. fowleri infection is not a notifiable disease, this returned a low yield.

History of Naegleria fowleri

In 1899, the Austrian scientist Franz Schardinger published the first description of an amoeba that transforms into a flagellate, with drawings of the amoeba, cysts and flagellates. In 1912, Alexeieff coined the name Naegleria, but physicians at the time thought that the genus did not cause disease in humans.3 It was not until the late 1960s that Naegleria was implicated as the cause of PAM by the work of Adelaide pathologists Malcolm Fowler and Rodney Carter, and of South Australian rural general practitioner Robert Cooter. In 1965, it was first proposed that the organism entered the CSF through the cribriform plate after Fowler isolated the organism in autopsy specimens. Following communication of his findings, Cooter and colleagues were able to directly observe the live amoeba in a CSF sample from a 10-year-old boy who presented with meningoencephalitis.4,5

Pathophysiology

N. fowleri lives and multiplies in warm freshwater areas, and acquisition is often associated with water-based recreational activities.6 Infection may occur when contaminated water is flushed into the nasal cavity. After penetrating the nasal mucosa and passing through the cribriform plate, trophozoites migrate along the olfactory nerve directly into brain tissue. Cases are almost universally fatal, although survival has been reported in the literature following early diagnosis and management.7,8

Epidemiology

The worldwide incidence of PAM is not accurately known,9 and the disease is likely to be under-diagnosed and under-reported. In the developing world, numerous factors affect accurate identification, including a lack of resources or expertise in microbiological diagnosis; prioritising management of other infections that are more common; and cultural beliefs that prevent autopsies.9 Higher water temperatures, inadequate sanitation, unsafe water sources, and religious ablution practices, such as the use of Neti pots for nasal cleansing, could potentially increase the risk for acquiring PAM.10,11 N. fowleri is a thermophilic organism and would therefore be expected to occur more frequently in tropical areas; however, the majority of cases are reported from subtropical or temperate regions.12 In a study in Karachi, Pakistan, N. fowleri was recovered from 8% of 52 domestic water taps that were sampled.13

An epidemiological review of PAM cases in the United States showed that N. fowleri infections are rare and primarily affect younger males exposed to warm recreational freshwater in the southern states.14–16 There are two case reports of patients who acquired N. fowleri from using treated municipal water for nasal irrigation,17 and another patient who contracted the disease from inadequately treated municipal water.18

In Australia, Dorsch and colleagues reported 20 cases of PAM, 13 of which occurred between 1955 and 1972 in South Australia. These cases were attributed to household water that was piped overland for long distances,19 allowing it to be heated to temperatures that promoted growth of the amoeba.5 After the introduction of continuous water chlorination in 1972, only one further case was reported in South Australia in 1981.19 In Queensland, only three previous patients have been described in the literature: one from Mount Morgan who survived, one from Charters Towers,19 and one referred from North West Queensland to Townsville Hospital.2

Clinical challenges

Patients with PAM present with the same symptoms as those with bacterial meningitis, and clinical differentiation between the two conditions is impossible. Patients often have a history of recent exposure to warm fresh water, although the definite exposure event is not always identified.9 The incubation period ranges from 2 to 15 days, and presenting symptoms may include meningism, fever, confusion and signs of elevated CSF pressure, such as seizures or coma.14

Diagnosis is made more difficult in North Queensland by the vast distances between remote towns in the western part of the state. Townsville Hospital services an area of nearly 150 000 km2 and has the only dedicated paediatric intensive care unit north of Brisbane. Patients with PAM inevitably require intensive care unit management and tertiary level investigations. Obtaining CSF samples for formal microscopic diagnosis is often impossible in small clinics with limited medical imaging or local laboratory services, and where performing a lumbar puncture is contraindicated by symptoms of raised intracranial pressure. Because of the rarity of the infection, greater awareness of PAM among primary health care professionals is required in order to increase suspicion in a clinically compatible case. Most importantly, education about prevention is essential for the continued health of rural communities, of which local medical professionals are a vital part. To this end, recent guidelines for the management of encephalitis20 include assessing risk factors for this condition and performing appropriate testing, as described below.

Diagnostic challenges

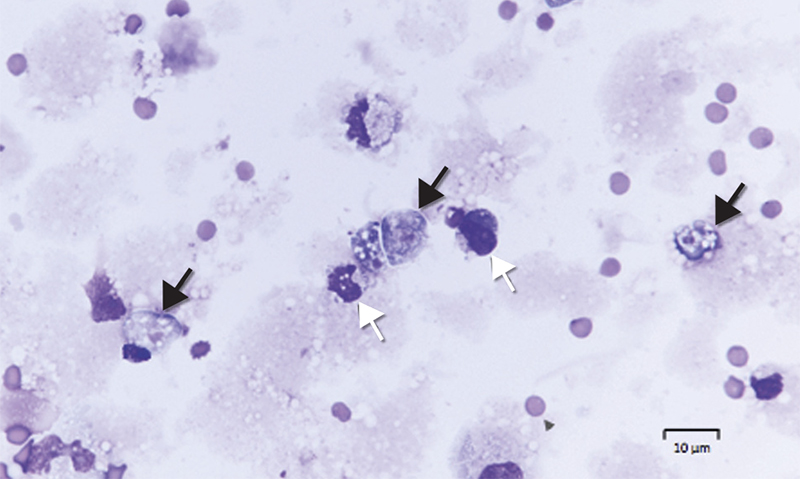

Diagnosis requires identification of motile trophozoites in CSF or characteristic morphology in stained specimens by a trained microbiologist (Box 1), with confirmation using molecular methods (PCR) or culture (Escherichia coli lawn culture). The trophozoites are visible in a wet unstained preparation of CSF (magnification, × 400), exhibiting sinusoidal movement by means of lobopodia; however, specimens need to be examined very soon after collection, as the amoebae degenerate rapidly in vitro and can be easily mistaken for leucocytes.

CSF chemistry is not diagnostic and will usually reveal a similar pattern to that of bacterial meningitis (Box 2). PCR analysis is performed using in-house methods at reference laboratories, and confirmation is often posthumous due to the rapid decline experienced by most patients. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has developed a multiplex real-time TaqMan PCR assay to simultaneously identify three free-living amoebae (N. fowleri, Acanthamoeba spp. and Balamuthia mandrillaris) in clinical specimens.21 In Queensland, the pathology laboratory which performs all N. fowleri molecular testing uses primers and probes in line with the method of Qvarnstrom and colleagues.21 Culture may take several weeks and is difficult to perform.

Treatment

Given the limited data available, there are no set guidelines for antimicrobial therapy; however, it can be extrapolated from cases of patients who have survived that combination therapy with multiple anti-parasitic agents is required.

In 1969, Carter was able to demonstrate the sensitivity of the organism to amphotericin B (AMB) and it has remained the mainstay for treatment of PAM to this day.22 AMB has been used in all patients who have survived the illness.23 N. fowleri is highly sensitive to AMB in vitro with a minimum amoebicidal concentration of 0.01 μg/mL,24 and no resistance has been reported. Conventional AMB is preferred to liposomal forms as it can be given intrathecally as well as intravenously. Despite this, only a few patients have survived.25

Other antifungal drugs, such as miltefosine and the azoles, have all shown in vitro activity against N. fowleri.22–24 Miconazole has synergistic activity when combined with AMB, and fluconazole is used as first line in combination therapy.

Miltefosine is a protein kinase B inhibitor that was originally developed as an antineoplastic agent. It also has anti-parasitic activity and is used for the treatment of leishmaniasis. Schuster and colleagues26 reported that miltefosine showed in vitro activity against free-living amoebae, including N. fowleri, Acanthamoeba spp. and B. mandrillaris. Recently, miltefosine has been used in the treatment of Acanthamoeba granulomatous amoebic encephalitis and PAM. Linam and colleagues27 described the case of a child treated for PAM with combination therapy including amphotericin, miltefosine, fluconazole and rifampicin, who survived with no significant neurological sequelae.

Rifampicin is commonly used in the treatment of PAM; however, it has variable central nervous system penetration and poor efficacy in vitro.24 It may also reduce the efficacy of the azole drugs due to cytochrome P450 interactions. Although azithromycin has shown some in vitro and in vivo activity against N. fowleri, the other macrolides are less effective.9 Atypical agents such as the diamidines and chlorpromazine have been studied in animal models but have yet to be utilised clinically.24,28

Public health

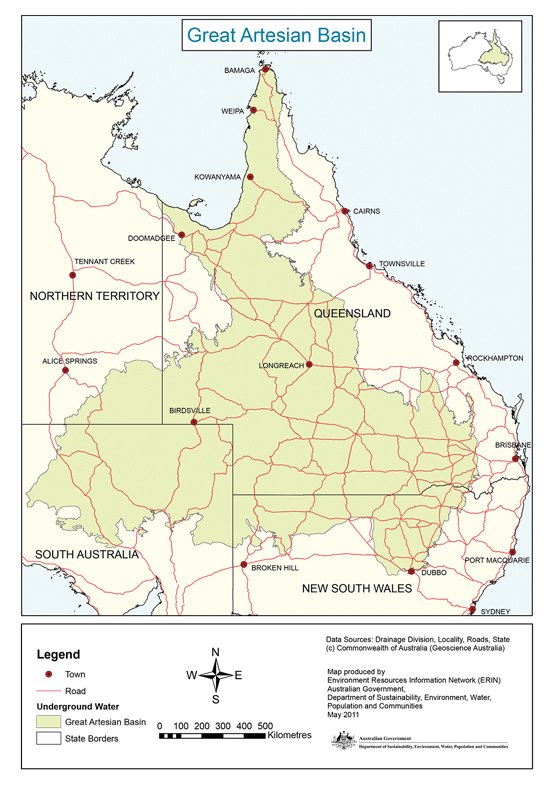

As described, our patient was probably the third child to die with PAM in 14 years in a small area with a tiny population on remote Queensland cattle stations. As a response to the third death, a public health investigation found large numbers of N. fowleri at the patient’s homestead. In this district, water was sourced from deep artesian bores at about 60°C (Box 3) and cooled in open surface dams before being piped hundreds of metres on the surface to households, keeping water temperatures high. It was noted that the cases described in North Queensland were of children too young to be swimming in surface waters, the assumption being that they contracted the disease in the home environment. There had never been water treatment or filtration in the homesteads for generations; the clarity and taste of the bore water had often been a source of pride for owners. The difference in the present era of rural life was the advent of modern facilities, allowing the heated bore water to be pressurised via taps, hoses, toys and showerheads and delivered directly into the homestead.

The public health hypothesis was that:

-

Hot artesian bore water and long surface pipelines promote large concentrations of N. fowleri, which can be sucked into water pipes from sediments, particularly in drought years.

-

There had been no form of treatment for apparently clean water.

-

In recent years, among young families with modern water facilities, there were many more opportunities for water to be forced into a vulnerable (non-immune) child’s nose at pressure.

-

Simple filtration and disinfection of all water for washing and playing would prevent child deaths on these properties.

The public health dilemma was whether health promotion for a single, rare disease could be cost-effective or gain traction among rural people possibly reluctant to accept an expensive treatment of their water. Untreated surface water can also lead to a whole spectrum of gastrointestinal diseases, even if these were not familiar to the remote communities. It was decided that a health promotion campaign about domestic water filtration and treatment could protect not only from PAM but also from a range of other diseases.

The family of our second confirmed patient embarked on a rural education campaign of their own to prevent any further deaths from PAM or other waterborne diseases, culminating in an episode of the television series Australian Story in November 2015.29 To coincide with this story, public health physicians gave a series of talks to communities and health staff across a wide area of outback Queensland. To follow up the face-to-face campaign, Queensland Health released a safe water booklet with advice on cost-effective filtration and disinfection.30 As a result, many rural properties and some small towns are installing water treatment equipment for the first time. The South Australian and Western Australian governments have online education resources specifically targeting rural communities at risk of amoeba acquisition,31,32 with the primary focus on prevention. The aim of the Queensland public health booklet was to provide a more comprehensive education document for water treatment in rural communities.30

Conclusion

We hope an increased awareness of N. fowleri and its association with warm, non-chlorinated water provides an opportunity for counselling families about safe water use: avoiding diving or jumping into or squirting untreated water, and disinfecting or filtering water used for washing and playing, as well as for drinking. In particular, bore water at warm or hot temperatures and other warm water sources should be considered ideal reservoirs for this organism. In the clinical setting, difficulties with analysing CSF make it unlikely that an accurate diagnosis could be provided in a remote environment. The presentation of an acutely unwell child with a history of bore water exposure and signs of meningitis or encephalitis should, however, prompt consideration of PAM as a potentially life-threatening diagnosis. Our experience with this disease clearly demonstrates the crucial role of medical professionals working in rural and remote Australia in primary prevention of this almost universally fatal condition.

Box 1 –

Microscopy of cerebrospinal fluid of Patient 2,showing trophozoites (Giemsa stain, black arrows) and mononuclear leucocytes (white arrows)

Box 2 –

Analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in patients with primary amoebic meningoencephalitis at Townsville Hospital

|

|

Microscopy |

White cell count (106/L) |

Polymorphonuclear leucocytes |

Protein (mg/L) |

CSF:blood glucose |

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Normal |

No organisms |

< 1 |

0 |

< 0.4 |

> 0.6 |

||||||||||

|

Patient 1 |

Motile trophozoites |

7200 |

91% |

3900 |

0.17 |

||||||||||

|

Patient 2 |

Motile trophozoites |

240 |

54% |

2700 |

0.12 |

||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 –

Great Artesian Basin

The Great Artesian Basin, from which bore water comes, covers a vast area of rural Australia. Western Queensland has a particularly wide coverage, and rural properties use bore water extensively.

Source: Australian Government Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities, 2011. Available at http://www.agriculture.gov.au/water/national/great-artesian-basin (accessed Aug 2016).

more_vert

more_vert