Polypills have been approved in more than 30 countries, but worldwide experience with and availability of polypills remain limited, unlike fixed-dose combinations in other diseases such as HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria. In this Series review, we aim to propose a guide for the use of polypills in future research and clinical activities and to synthesise contemporary evidence supporting the use of polypills for prevention of atherosclerosis. Polypill uses can be categorised by population and indication, both of which influence the balance between benefits and risks.

Preference: Infectious Diseases and Parasitology

434

[Comment] Modifying the trajectory of asthma—are there lessons from the use of biologics in rheumatology?

As we move towards a new era of precision medicine in high-income countries, with the conceptual framework of the right drug, for the right patient, and at the right time, it is useful to consider variations in the availability of targeted therapies for different diseases.

News briefs

Gene linked to “Rain man” brain disorder

Murdoch Childrens Research Institute (MCRI) researchers have discovered a new gene linked to a congenital brain abnormality experienced by the person who inspired the movie Rain Man. Associate Professors Paul Lockhart and Rick Leventer led an international team which has discovered the first gene, called Deleted in Colorectal Cancer (DCC), known to cause the loss of the main connection between the two halves of the brain, in the absence of any other syndromes linked to the condition. About one in 4000 babies are born with agenesis of the corpus callosum (ACC). Symptoms of ACC, where the corpus callosum is missing, are varied but can include intellectual disability, autism and cerebral palsy. Individuals with ACC who also have the DCC gene change often struggle with “mirror movements”. This means if they move one hand, the other hand automatically moves in the same way. This causes problems with everyday tasks including eating, washing the dishes, writing, driving a car and using a mobile phone or tablet. Lockhart and Leventer’s study suggests that individuals with ACC caused by mutations in this gene have much better neurodevelopmental outcomes than people with ACC linked to a particular syndrome. This holds important implications for decision making if the condition is detected during prenatal testing, they wrote. “The results of this research will provide better information to parents regarding potential outcomes for their children, helping to make more informed reproductive decisions,” Lockhart said. “Our research also provides important new information about how nerves connect to the appropriate part of the brain during development of the embryo. This has potential implications for our understanding of a broad range of neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism spectrum disorder. This gene is playing a role in how nerves connect with each other and transfer information. Deficits or problems in this process are emerging as associated with autism spectrum disorder.” The finding was published in Nature Genetics.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ng.3794

Life expectancy booming

By 2030 there is a greater than 95% probability that life expectancy at birth among Australian men will surpass 80 years, and a greater than 27% probability that it will surpass 85 years, according to research published in The Lancet. Researchers from Imperial College London and other international sites, developed 21 forecasting models, then applied the approach to project age-specific mortality to 2030 in 35 industrialised countries with high quality vital statistics data. They used age-specific death rates to calculate life expectancy at birth and at age 65 years, and probability of dying before age 70 years. The increase in life expectancy will be largest in South Korea, some western European countries and some emerging economies. South Korean women are predicted to live beyond 86 years by 2030, with a 57% probability that their life expectancy will be beyond 90 years. The smallest increases will be in the USA, Japan, Sweden, Greece, Macedonia, and Serbia. “Countries with high projected life expectancy are benefiting from one or more major public health and health-care successes. Examples include high-quality healthcare that improves prevention and prognosis of cardiovascular diseases and cancers, very low infant mortality, low rates of road traffic injuries and smoking (Australia, Canada, and New Zealand), and low body-mass index (French and Swiss women) and blood pressure (Canada and Australia).”

Funding no brainer

Funding cuts have left untouched hundreds of brains donated for medical research in Australia untouched, according to a recent exclusive report in the Weekend Australian.

The brains were collected from donors since 2005 when a national network of brain banks was set up from a $4.5 million 10-year funding allocation from the National Health and Medical Research Council.

But when that funding ended in 2014, individual States had to fund and maintain their own collections of brains.

This has proved to be more difficult than anticipated, with State brain banks struggling to keep their collections and progress their research into neurological diseases.

Some State banks are close to shutting down, but a more permanent source of federal funding is being sought for the national network so all the banks can keep operating.

Chris Johnson

Vaccinations debate gets a shot in the arm

One Nation leader Pauline Hanson has sparked outrage and ignited a fresh debate over vaccinations by saying the Government was blackmailing parents into immunising their children.

Reinforcing her belief that vaccinations have links to autism and can cause other ill effects, Senator Hanson suggested parents have their children tested first to determine if they will react adversely to the shots.

“I’ve heard from parents and their concerns about it and what I have said is I advise parents to go out and do their own research with regards to this,” she told the ABC’s Insiders program.

“Look, there is enough information out there. No-one is going to care any more about the child than the parents themselves. Make an informed decision.

“What I don’t like about it is the blackmailing that’s happening with the Government. Don’t do that to people. That’s a dictatorship. I think people have a right to investigate themselves. If having vaccinations and measles vaccinations is actually going to stop these diseases, fine, no problems.

“Some of these – parents are saying – vaccinations have an effect on some children. Go and have your tests first. You can have a test on your child first.

“Have a test and see if you don’t have a reaction to it first. Then you can have the vaccination. I hear from so many parents. Where are their rights? Why aren’t you prepared to listen to them? Why does it have to be one way?”

Senator Hanson did not stipulate what test she was referring to and some days later apologised, saying she was wrong about it.

She has also stated that her comments were only a personal opinion and admitted that she had had her own children vaccinated.

But she maintains her distaste for the current Government policy to withhold some welfare payments and childcare fee rebates from parents who don’t fully immunise their children.

“I’m not saying to people don’t get your children vaccinated. I’m not a medical professional” she said while campaigning in the WA State election.

“I had my children vaccinated. I never told my children not to get their children vaccinated. All I’m saying is get your advice.”

Her initial remarks, however, have caused a backlash from a host of experts, commentators and politicians – including Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull.

“If parents choose not to vaccinate their children, they are putting their children’s health at risk and every other person’s children’s health at risk too,” Mr Turnbull said.

Health Minister Greg Hunt described Senator Hanson’s comments as “incorrect in fact” and not what a Member of Parliament should be making.

He also acknowledged that the so-called No Jab, No Pay policy is a strong and tough policy, but one he backed 100 per cent.

“I take a very clear, strong view of this. Vaccination is fundamental to protecting not just our own children, but everybody else’s children,” Mr Hunt said.

“There are decades and decades of different sources of evidence and practise and simply reduced incidences of conditions such as mumps and measles, rubella, whooping cough.

“So the evidence is clear, overwhelming and very broadly accepted.”

The AMA has provided much of that evidence over a long period of time.

Responding to Senator Hanson’s controversial remarks, AMA President Dr Michael Gannon praised the national immunisation program.

“The false claims, the mistruths, the lies that you can find on the internet are of a great concern to doctors,” Dr Gannon said.

“The national immunisation program is a triumph. There is good news in this story – 95 per cent of one-year-olds in Australia are fully vaccinated, 93 per cent of five-year-olds are fully vaccinated.

“But we know that a lot of parents are doing this with some reservations, and that’s of great concern.

“The person to give you the most accurate information about the benefits of vaccination to allay your concerns is your local immunisation provider. In many cases, that’s your family GP.

“I can assure you that there is some absolutely galling rubbish available to parents on the internet.

“They need to be taught how to find credible sources of information. Anything which weakens this most important of public health measures really needs to be stepped on.”

Meanwhile, a new national survey has revealed that health care providers are refusing to treat one in six children who are not up to date with their vaccinations.

The sixth Australian Child Health Poll was conducted and released by the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne and published in March under the title Vaccination: Perspectives of Australian Parents.

It also found that 95 per cent of parents kept their children up to date with vaccines, but that almost a third of parents held concerns about vaccination safety.

Dr Gannon labelled it an interesting and important study.

“It refers to health care providers. I would be surprised if we were talking about doctors. It’s not ethical to deny treatment to unvaccinated children,” he said.

“I suspect we would hear many, many complaints if this was the fact, that these were doctors refusing to treat these kids.

“Certainly legally they can refuse treatment, but ethically they shouldn’t. Parents who deny their children the individual benefits of vaccination against preventable and infectious disease are already doing their child a disservice. Doctors would not seek to enhance that disadvantage.

“This study is a good news story in many ways. It shows the overwhelming support that the vaccination program enjoys amongst Australian parents.”

Director of the Child Health Poll, paediatrician Dr Anthea Rhodes, said the survey suggested a worrying pattern of practice not previously identified in Australia.

“All children, regardless of their vaccination status, have an equal right to health care,” Dr Rhodes said.

Chris Johnson

Critical antibiotic resistant superbug list released by WHO

The World Health Organisation has released a list of the most critical bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics, in the hope that governments will act soon.

These bugs could pose a risk to patients in hospitals and nursing homes by causing severe and often deadly infections among patients requiring devices like ventilators or blood catheters.

The bacteria have built-in abilities to find new ways to resist treatment. They can also pass along genetic material to allow other bacteria to also become drug resistant.

According to Dr Marie-Paule Kieny, WHO’s Assistant Director-General for Health Systems and Innovation, “This list is a new tool to ensure R&D (research and development) responds to urgent public health needs.”

“Antibiotic resistance is growing, and we are fast running out of treatment options. If we leave it to market forces alone, the new antibiotics we most urgently need are not going to be developed in time,” she said.

Related: Superbugs could be ‘worse than global financial crisis’: World Bank

The WHO have released 12 bugs divided into three categories based on the urgency of the need for new antibiotics.

The superbugs are:

Priority 1: CRITICAL

- Acinetobacter baumannii, carbapenem-resistant

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa, carbapenem-resistant

- Enterobacteriaceae, carbapenem-resistant, ESBL-producing

Priority 2: HIGH

- Enterococcus faecium, vancomycin-resistant

- Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-resistant, vancomycin-intermediate and resistant

- Helicobacter pylori, clarithromycin-resistant

- Campylobacter, fluoroquinolone-resistant

- Salmonellae, fluoroquinolone-resistant

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae, cephalosporin-resistant, fluoroquinolone-resistant

Priority 3: MEDIUM

- Streptococcus pneumoniae, penicillin-non-susceptible

- Haemophilus influenzae, ampicillin-resistant

- Shigella, fluoroquinolone-resistant

Dr Rietie Venter is Head of Microbiology at the Sansom Institute for Health Research at the University of South Australia highlights that it was one of these organisms that was responsible for an American woman’s death earlier this year as the organism was resistant to all antibiotics available in the US.

Related: We need more than just new antibiotics to fight superbugs

Despite this reality, research into antimicrobials is still not very well supported by pharmaceutical companies.

“We can only hope that the publication of this list would translate into the necessary funding to develop new antimicrobials and prevent us from slipping into a world without effective antimicrobials where small injuries would once again be life-threatening and modern medicine such as transplants would be impossible to practice,” she said.

According to Professor Ramon Shaban, President of the Australasian College for Infection Prevention and Control, antimicrobial resistance shouldn’t be considered just a problem for clinicians in human sectors.

“It is a whole of society challenge, and many of the solutions are non-clinical. It, like infection control, is everyone’s business,” he concludes.

Latest news

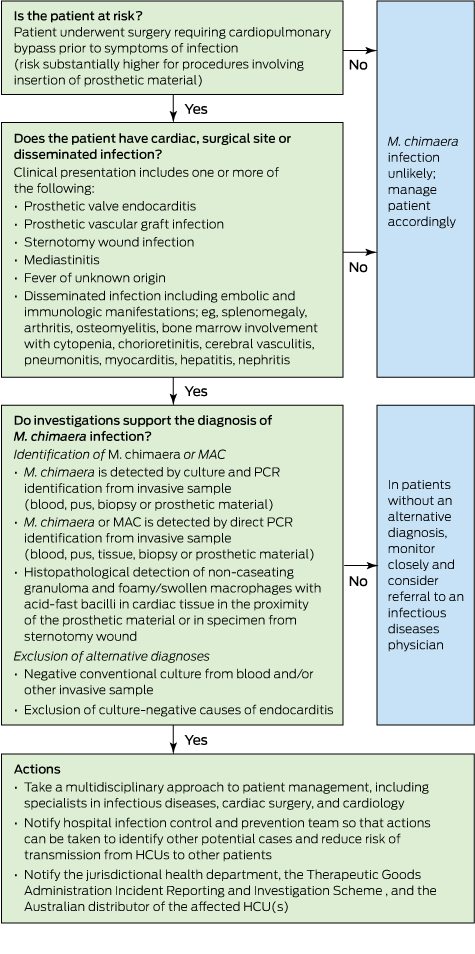

Mycobacterium chimaera and cardiac surgery

Recent reports from the United Kingdom, Europe and the United States have described a small number of invasive infections with Mycobacterium chimaera associated with cardiac surgery that have been associated with high mortality. M. chimaera is likely to have been transmitted to patients by aerosols generated from contaminated heater–cooler units used during cardiopulmonary bypass. Here we describe the outbreak and discuss the relevance for Australian clinicians. Our primary objective is to raise awareness locally of this rare but serious health care-associated infection so that patients can be promptly diagnosed and optimally treated.

To formulate an evidence-based overview of the topic, as applied to clinical practice, we conducted a PubMed search of original papers and review articles in the period 2004–2016 using the term “Mycobacterium chimaera”, along with publications released by government agencies, public health bodies and medical device regulatory authorities, and selected conference presentations.

Initial outbreak description

In 2012, clinicians at the University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland, diagnosed two patients with ultimately fatal infections due to M. chimaera, a member of the M. avium complex (MAC) group of slow-growing non-tuberculous mycobacteria.1,2 The patients — one with prosthetic valve endocarditis and the other with bloodstream infection — had no known direct community or inpatient contact with each other, but had both undergone cardiac surgery with insertion of prosthetic material at the same hospital (in 2008 and 2010).1 Typing suggested that the strains from these two cases were genetically related and were, in addition, distinct from M. chimaera strains isolated from respiratory samples from other patients at the same hospital.

Detection of these two cases of an unusual and fatal infection prompted an outbreak investigation for a potential hospital source.3 Given the propensity of MAC organisms to be found in association with water, the investigation focused on points of contact between water and patients undergoing cardiac surgery. M. chimaera was isolated from the water circuit of five heater–cooler units (HCUs).3 These devices are used during cardiopulmonary bypass to regulate temperatures of extracorporeal blood and cardioplegia solution, and do not have direct contact with patients. When contaminated HCUs were in operation, air samples from the operating theatre itself and its exhaust air flow were also positive for M. chimaera. The authors hypothesised that aerosolised M. chimaera from contaminated HCUs was the source of infection. Subsequent experiments performed in a cardiac operating theatre with an ultraclean laminar airflow system confirmed aerosolisation of M. chimaera from a contaminated HCU and demonstrated smoke dispersal from an HCU to the operative field in 23 seconds when the unit’s airflow was directed towards the operating table.4

In parallel, a case detection exercise identified another four patients with invasive M. chimaera infection at the same hospital, with all six having undergone cardiac surgery with insertion of prosthetic material between August 2009 and March 2012. A nationwide investigation involving the 16 Swiss centres that perform cardiac surgery was mandated by the Federal Office of Public Health in 2014, and this identified eight contaminated HCUs but no further patient cases.5 Swiss authorities made a public announcement about the cluster in July 2014.6

International reports and response, including Australia

After the initial reports from Switzerland, invasive M. chimaera infections following cardiac surgery involving cardiopulmonary bypass have been reported in the Netherlands, Germany, the UK and the US.7–10 At least 50 cases have been diagnosed worldwide (Professor Hugo Sax, University Hospital Zurich, personal communication). Seventeen probable cases identified in the UK had undergone heart valve repair or replacement in ten National Health Service (NHS) trusts since 2007.9 A nationwide prospective case finding investigation, using a mandatory reporting system, performed in Germany from April 2015 until February 2016 identified five patient cases from three cardiac surgery centres.10 All five patients were exposed to HCUs manufactured by a single manufacturer. M. chimaera was also identified in samples from new machines and the environment at the manufacturing site.10 As a result of this investigation, German public health authorities triggered notifications of a suspected common source for the outbreak via the European Early Warning and Response System and under the World Health Organization International Health Regulations framework.10

Public Health England coordinated testing of 24 HCUs (LivaNova [formerly Sorin Group]); also the manufacturer of the devices used in Zurich) at five NHS trusts.9 M. chimaera was culturable from water sampled from 15 of the units, and from surrounding air for about a third of the devices while they were running.9 The manufacturer issued a field safety notice in June 2015 identifying the risk of contamination by bacteria and subsequent aerosolisation during operation (http://www.livanova.sorin.com/products/cardiac-surgery/perfusion/hlm/3t). The notice recommended enhanced disinfection with updated instructions for use including revised recommendations for operation, disinfection and microbial monitoring.

In October 2015, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a Safety Communication to raise awareness of the issue of M. chimaera infections associated with HCUs and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued guidance for health care facilities, health care professionals and patients.11,12 In the context of heightened surveillance, in November 2015 the Pennsylvania Department of Health reported clusters of patients with non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections among patients exposed to open heart surgery at two hospitals.13 Whole-genome sequencing of M. chimaera strains from 11 infected patients and five HCUs (Stöckert 3T [LivaNova]) from two US states (Pennsylvania and Iowa) confirmed their genetic relatedness, strongly suggesting “a point-source contamination of Stöckert 3T heater–cooler devices”.14

In Australia, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) announced an investigation into this issue and released recommendations to health facilities in May 2016.15 In August, the TGA reported one case of possible patient infection with M. chimaera following open cardiac surgery.16 In October, a TGA alert identified the affected product as the Stӧckert 3T HCU, and reported that in Australia “25% of these devices have tested positive for the Mycobacterium chimaera organism or other organisms”, but all positive machines were manufactured before September 2014.17 In keeping with a recent recommendation from the FDA,18 the TGA recommended that health services “consider transitioning away from” 3T devices manufactured before September 2014.17 Ten HCUs from four Western Australian hospitals (of 15 HCUs tested from five hospitals) were colonised by genetically related M. chimaera strains, along with other mycobacteria.19 The M. chimaera strain cultured from a pleural biopsy of a patient who had undergone surgery at one of these hospitals was considered distinct from the HCU strains, suggesting that the HCU was not the source of infection in this case.19 Subsequently, whole-genome sequence comparisons of 43 M. chimaera strains from HCUs in four Australian states and four regions of New Zealand confirmed close genetic relatedness of these strains with those from HCUs in the northern hemisphere.20 Whole-genome sequencing also showed that a patient isolate was identical to an isolate from an HCU used in the facility during the patient’s surgery.20

While there is no clear consensus on how to best manage HCUs to minimise risk, some recommendations have been released.9,12,14,21,22 The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) released national infection control guidance in September 2016, outlining recommended risk mitigation strategies for Australian health service organisations.23 A simple precautionary step is to ensure that HCU ventilation airflow is directed away from the patient and towards the theatre exhaust whenever operational, although it is not clear whether this eliminates risk entirely.4 Other options, at least until M. chimaera contamination is excluded by microbiological testing, include physical removal of HCUs from the operating theatre (to an adjacent room) — as was nationally implemented in the Netherlands8 — or placement of the unit in a custom built sealed container that directs ventilation outflow out of the operating theatre, as described in Zurich.3 The TGA and ACSQHC note that the latter approaches may not be feasible in all facilities and should be planned in discussion with the Australian sponsor of the device to ensure it will not compromise device function.15,23

Clinical description of HCU-related M. chimaera infection

Although the risk of invasive M. chimaera infection following cardiac bypass surgery in Australia is estimated to be very small, the long incubation period and unusual non-specific clinical presentation mean that general practitioners and specialists need to know when to suspect this rare condition and how to diagnose it (Box).

The diagnosis in cases so far has been complicated by long delays between surgery and symptom onset, non-localising clinical presentations, and the need for directed microbiological testing using special tests. The following summary is compiled from existing published reports: six confirmed cases in Switzerland,1,3 which were subsequently reported in combination with three confirmed and one probable case from the Netherlands and Germany,7 five additional confirmed cases in Germany,10 and 17 probable cases in the UK.9

Although the risk of infection appears to relate principally to cardiac bypass procedures involving insertion of prosthetic material, there is one report of infection following coronary artery bypass grafts.10 HCUs are also used during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, but no cases of infection have been attributed to this exposure.9 Establishing the risk of infection among exposed patients is difficult given incomplete data and the possibility that some cases have either been missed or remain in latent phase, but the risk is very low. Public Health England reported that about 100 000 patients underwent valve repair or replacement between 2007 and 2014, and estimated that the incidence rate of M. chimaera infections among these patients was 0.4 (95% CI, 0.2–0.7) per 10 000 person-years of post-operative follow-up.9

The period during which patients underwent initial cardiac surgery extends from 2007 to 2013.7,9 According to Haller and colleagues,10 the manufacturer involved in their investigation confirmed that HCUs delivered before mid-August 2014 may have been contaminated with M. chimaera. The latent period from cardiac surgery to diagnosis has ranged from 3 months to 5 years (median, 19 months among UK patients).9,10 Among the 15 European patients, median age was 63 (range, neonate to 80 years) and 14 were male.7,10 Patients have not, in general, been significantly immunocompromised.

Patients have presented with endocarditis or other cardiac infection, disseminated or non-cardiac infection, and surgical site infection.3,7,9 Fourteen of 15 European cases had cardiac infection: endocarditis, prosthetic valve infection, paravalvular abscess, graft infection and one case of myocarditis. In many cases, however, initial presentation was with non-cardiac disease: bone infection (osteoarthritis, spondylodiscitis), cholestatic hepatitis, nephritis or surgical site infection. Other manifestations included splenomegaly, ocular disease (panuveitis or chorioretinitis), and mycobacterial saphenous vein donor site infection.7 Of 13 probable cases in the UK with clinical description, six presented as cardiac infection, five as disseminated or non-cardiac infection, and two as surgical site infection. Several patients have been misdiagnosed with sarcoidosis or connective tissue disease, and commenced on corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents.1,7,24

Diagnosis of M. chimaera infection requires directed investigations. Public Health England has recommended that patients with endocarditis and/or disseminated infection should undergo mycobacterial culture and molecular testing (16S rRNA gene sequencing) of tissue samples and three sets of mycobacterial blood cultures in addition to routine diagnostics.9 Patients with wound infections unresponsive to routine antibiotic therapy require tissue or bone samples to make the diagnosis rather than swabs.9 To permit harmonised assessment of patients who have previously presented with a syndrome that may be consistent with M. chimaera infection related to HCU exposure, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control has produced definitions for retrospective identification of probable and confirmed cases.22

Antimicrobial therapy has centred on combination treatment with clarithromycin, rifabutin and ethambutol, with the addition of fluoroquinolone or amikacin in some cases.3,7 Clinicians involved proposed that initial antimicrobial therapy to reduce the burden of infection should be followed by surgical intervention followed by further antimicrobial therapy.5 Serial fundoscopy to monitor chorioretinitis may be a useful tool to monitor response to therapy.3 Nine of 17 patients in the UK died.9 Six of 15 European patients with confirmed or probable infection died.7,10 In four cases reported by Kohler and colleagues,7 death was attributed to uncontrolled M. chimaera infection despite directed therapy (15–375 days).7 Three patients were being monitored following completion of treatment at the time of reporting.

In Australia, when a patient case of M. chimaera infection is confirmed or an HCU is found to be contaminated, this should be reported to the relevant hospital infection control team, the jurisdictional health department, the TGA Incident Reporting and Investigation Scheme, and the Australian distributor of the affected unit(s).

Summary

There is an evolving international outbreak of M. chimaera infection associated with contaminated HCUs used for cardiac bypass surgery. While the risk to exposed patients is very low, cases are challenging to detect and associated with high mortality. Diagnosis requires an awareness of this possibility among clinicians and microbiologists, particularly when evaluating patients presenting with one or more of sternal wound infection or mediastinitis, prosthetic valve endocarditis, early prosthetic valve failure or systemic inflammatory condition. Further, these complications may present months or years after a bypass procedure. A first case has been identified in Australia, and we must remain vigilant in order to detect and manage any further cases.

Streptococcus pyogenes pericarditis in a healthy adult: a common organism in an uncommon site

Clinical record

A 64-year-old man presented with progressive dyspnoea, chest pain and rigors 5 days after returning from the United States. This was preceded by a 3-week history of sore throat, left submandibular lymphadenopathy and non-productive cough and fevers, which began while he was overseas.

The patient’s overseas travel was limited to major cities. His past medical history was unremarkable. He did not smoke, consume excessive alcohol or use illicit drugs. The patient did report a dental root infection in the week before travel, which completely resolved following drainage.

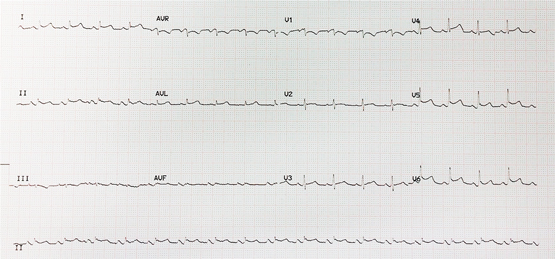

On presentation to our hospital, the patient was alert and afebrile but hypotensive with blood pressure of 80/60 mmHg on a peripheral vasopressor infusion. Vital signs included a heart rate of 106 beats/min, respiratory rate of 36 breaths/min and oxygen saturation of 99% on supplemental oxygen (4 L/min). Heart sounds were muffled with no pericardial rub heard. Jugular venous pressure was elevated and his electrocardiogram showed low voltage QRS complexes and saddle-shaped ST elevation laterally (Figure 1).

Inflammatory markers revealed a white cell count of 26.7 × 109/L (reference interval [RI], 4–11 × 109/L) with predominant neutrophilia and a C-reactive protein level of 207 mg/L (RI, < 5 mg/L).

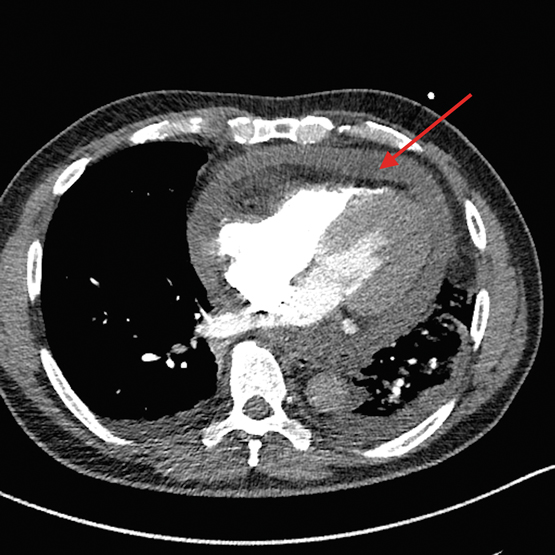

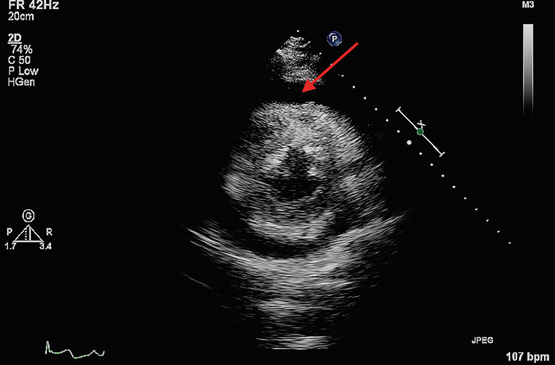

Chest x-ray showed left lower lobe consolidation with an ipsilateral effusion. Computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) was performed to rule out pulmonary embolism and unexpectedly revealed a 1.5 cm circumferential pericardial effusion (Figure 2). A transthoracic echocardiogram then confirmed tamponade physiology (Figure 3) and was used to guide emergency pericardiocentesis and pigtail catheter placement. About 350 mL of purulent straw-coloured fluid was drained, resulting in immediate haemodynamic improvement.

Biochemistry of the pericardial fluid showed an exudate with a glucose level of < 0.5 mmol/L (RI, 5.9–8.8 mmol/L), a lactate dehydrogenase level of 1270 U/L (RI, 276–517) and a protein level of 56 g/L (RI, 28–38 g/L), with a fluid–serum ratio of 0.875 (RIs based on the methods of Ben-Horin and colleagues).1 Microscopy yielded moderate numbers of gram-positive cocci with subsequent culture of Streptococcus pyogenes. Sequencing of the bacterial genome revealed this to be emm-1, sequence type 28. The pericardial drain was left in situ for 48 hours and drained a total of 975 mL. Analysis of pleural fluid showed a reactive, culture-negative transudate.

Serial echocardiograms during admission demonstrated increasing fibrinous organisation of the residual effusion. Despite this, the patient recovered completely after 4 weeks of intravenous benzylpenicillin and 2 weeks of oral amoxicillin. A transthoracic echocardiogram at 2 months showed complete resolution of the pericardial effusion without constriction.

Bacterial causes represent only 5% of infectious pericarditis cases in developed countries, with the vast majority attributed to viral infection or autoreactivity.2,3 Among bacterial pericarditis cases, Staphylococcus aureus is most frequently implicated (22–31%), while Streptococcus pyogenes is exceedingly uncommon.3 In the post-antibiotic era, there is an increasing trend towards haematogenous spread as the primary mechanism of pericardial infection, as opposed to direct extension from respiratory sources.2,3

Advances in molecular techniques have facilitated the identification of over 250 types of S. pyogenes based on sequencing of the emm gene, which encodes the M protein, an important determinant of organism virulence.4 Emm-1 is the most common isolate causing invasive disease in Australia.3 Sequence type 28 in particular is highly virulent and may account for the rare invasive syndrome described here.

Untreated, purulent pericarditis is invariably fatal and, even with appropriate therapy, mortality approaches 40%.3 In a review of eight cases of S. pyogenes pericardial effusion in children aged under 15 years, all progressed to tamponade and one to death.5 Any evidence of tamponade with a history of fever should prompt immediate echocardiography.2 Our patient was initially presumed to be in septic shock, and the diagnosis may have been missed or delayed if not for the incidental finding on CTPA.

Drainage of a pericardial effusion is recommended in the following settings: suspicion of neoplastic or bacterial aetiology; symptomatic effusion refractory to medical therapy; and any case of tamponade.2 Guidelines regarding duration of pericardial drainage are currently lacking, although it is acceptable to remove catheters when less than 30 mL is drained in 24 hours.2 In one case series of 1108 patients, 71% of patients with large effusions undergoing pericardiocentesis eventually required pericardiectomy owing to inadequate drainage.6 Bacterial effusions are particularly prone to rapid re-accumulation and loculation.2 Although pericardiocentesis is often the quickest and simplest method of drainage, a surgical approach via a subxiphoid window remains the gold standard.2

Purulent pericarditis is a rare but potentially fatal condition, which may present in otherwise healthy adults. Attention to early clinical signs of tamponade followed by prompt echocardiography may be lifesaving.

Lessons from practice

-

Streptococcus pyogenes pericarditis can rapidly progress to tamponade and death if left untreated.

-

Purulent pericarditis may be initially misdiagnosed as septic shock, potentially delaying pericardiocentesis.

-

Targeted antimicrobial therapy and adequate drainage of purulent pericardial effusions are key in allowing full clinical recovery.

Figure 1 –

Electrocardiogram showing low voltage QRS complexes and saddle-shaped ST elevation laterally.

[Correspondence] Protecting public health in Yemen

We strongly support Abdulrahman A Al-Khateeb’s (Oct 15, p 1877) and The Lancet’s (Oct 15, p 1852) call for humanitarian assistance in Yemen.1,2 Since 2015, the conflict has rapidly reached the severity and scale shared only by Level 3 emergencies in Syria, Iraq, and South Sudan. To put this into perspective, only 47% of the UN’s 2016 response plan was funded, leaving a shortfall of US$868 million to cover the basic needs of 14 million people.3 The effect of war in Yemen is compounded by a high vulnerability to natural disasters, unchecked non-communicable diseases and, as of October, a cholera outbreak that will affect 8 million people who lack adequate water and sanitation.

Association of maternal chronic disease with risk of congenital heart disease in offspring [Research]

Background:

Information about known risk factors for congenital heart disease is scarce. In this population-based study, we aimed to investigate the relation between maternal chronic disease and congenital heart disease in offspring.

Methods:

The study cohort consisted of 1 387 650 live births from 2004 to 2010. We identified chronic disease in mothers and mild and severe forms of congenital heart disease in their offspring from Taiwan’s National Health Insurance medical claims. We used multivariable logistic regression analysis to assess the associations of all cases and specific types of congenital heart disease with various maternal chronic diseases.

Results:

For mothers with the following chronic diseases, the overall prevalence of congenital heart disease in their children was significantly higher than for mothers without these diseases: diabetes mellitus type 1 (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 2.32, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.66–3.25), diabetes mellitus type 2 (adjusted OR 2.85, 95% CI 2.60–3.12), hypertension (adjusted OR 1.87, 95% CI 1.69–2.07), congenital heart defects (adjusted OR 3.05, 95% CI 2.45–3.80), anemia (adjusted OR 1.31, 95% CI 1.25–1.38), connective tissue disorders (adjusted OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.19–1.62), epilepsy (adjusted OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.08–1.74) and mood disorders (adjusted OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.11–1.41). The same pattern held for mild forms of congenital heart disease. A higher prevalence of severe congenital heart disease was seen only among offspring of mothers with congenital heart defects or type 2 diabetes.

Interpretation:

The children of women with several kinds of chronic disease appear to be at risk for congenital heart disease. Preconception counselling and optimum treatment of pregnant women with chronic disease would seem prudent.

more_vert

more_vert