The known In NSW, HBV vaccination of infants born to women at high risk commenced in 1987, and catch-up vaccination programs for adolescents in 1999.

The new Among women giving birth, targeted infant and school-based adolescent vaccination programs were associated with an 80% decline in HBV prevalence among Indigenous women by 2012. HBV prevalence in Indigenous women was higher in rural and remote NSW than in major cities, but among non-Indigenous and overseas-born women it was higher in cities.

The implications HBV prevention programs for Indigenous Australians should focus on regional and remote NSW and those for migrant populations on major cities. Antenatal HBV screening can be used to monitor population HBV prevalence and the impact of vaccination programs.

Chronic infection with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) can cause serious liver disease, and contributes worldwide to a significant burden of disease. Most chronic infections are acquired early in life, predominantly by maternal transmission.1 While its prevalence in Australia is generally considered to be low (under 2%), the prevalence of HBV infections in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (hereafter: Indigenous)2 people and in some migrant populations3 has been substantial.

A three-dose vaccine that is 95% effective in preventing HBV infection4 has been available in Australia since the early 1980s.5 In New South Wales, a targeted HBV vaccination program commenced in 1987.6 The program offered vaccination for babies born to parents from population groups considered to be at higher risk of HBV infection (defined as HBV prevalence ≥ 5%), including Indigenous Australians.7 In 1997, the National Health and Medical Research Council recommended universal HBV catch-up vaccination of children aged 10–16 years;8 in NSW, this was provided from 1999 to adolescents born since 1983 by general practitioners.9 The National Immunisation Program Schedule included universal infant HBV vaccination from May 2000. During 2004–2013, this was complemented by a NSW-wide school-based HBV vaccination catch-up program for year 7 students (born since 1991; online Appendix 1).5,7 In NSW, coverage through the universal infant program was reported to have exceeded 95% since 2003,10 and about 60% of eligible children not vaccinated as infants had been vaccinated through the school-based catch-up program in 2011 and 2012.11

To assess the impact of the vaccination programs on HBV prevalence in NSW, we determined its prevalence in women giving birth, as in Australia they are routinely screened for HBV during pregnancy.12 Our methodology was similar to that used in earlier studies that linked records of women giving birth and HBV infection notifications.2,3

Methods

Data sources and linkage

Data from two statutory registers were linked. The NSW Perinatal Data Collection (PDC) records all births in NSW of babies of at least 400 grams birth weight or 20 weeks’ gestation. The PDC contains details about the mother, such as year and country of birth, parity, postcode of residence, and Indigenous status, and about the birth, including the date of delivery and outcome. The NSW Notifiable Conditions Information Management System (NCIMS) is a population-based surveillance system that records reports of conditions deemed notifiable under the NSW Public Health Acts 1991 and 2010.13,14 The Act requires notification to NCIMS by any laboratory detecting HBV surface antigen (HBsAg), a marker of HBV infection, in a specimen submitted for diagnostic testing. The NCIMS records personal details, including date of birth, sex, postcode, and classification of the report as newly acquired hepatitis B infection or infection of unspecified duration (based on standard definitions15), notification date, and either the estimated onset date or date of the diagnostic test.

PDC records of women giving birth between January 1994 and December 2012 and NCIMS HBV notifications for the same period were available. Records from the two registers were linked by probabilistic matching of personal identifying details; this was conducted by the NSW Centre for Health Record Linkage (CHeReL), independently of the study investigators, to whom de-identified, linked data were provided for analysis. The reported false positive and negative rates for CHeReL linkage are about 0.5%.16

Study population and definitions

After linkage, we restricted our study population to women resident in NSW — using their postcode on the PDC record — of reproductive age (10–55 years at time of giving birth) who gave birth to their first child (ie, parity null) between January 2000 (when routine antenatal screening for HBV began17) and December 2012.

A woman was defined as having a chronic HBV infection at the delivery of her first child if there was at least one linked HBV notification in the NCIMS database that was recorded as unspecified and with a notification date earlier than the delivery date. Women with no linked HBV notifications were assumed to be not infected with HBV. Women with an HBV infection notified as being acute were excluded from the analysis, as it was unknown whether they would have cleared their acute infection or progressed to a chronic infection.

Statistical analysis

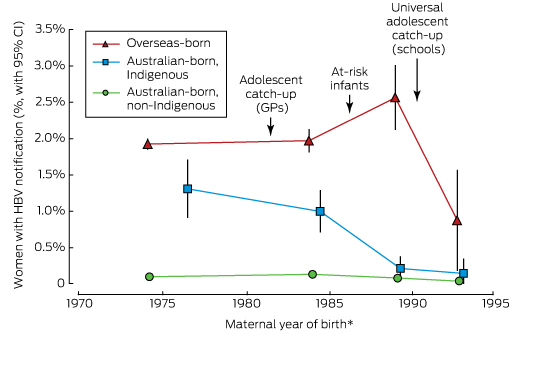

Women were categorised into four groups by their year of birth, which determined the likelihood of their being included in an HBV vaccination program: pre-vaccination era (maternal year of birth, 1981 or earlier); catch-up vaccination, predominantly GP-administered (1982–1987); at-risk newborn vaccination (1988–1991); and universal school-based catch-up and at-risk newborn vaccination (1992–1999; online Appendix 1). No women in our analyses were born during the period of universal HBV vaccination of newborns (from May 2000).

We also classified the women as Indigenous Australian, non-Indigenous Australian-born, or overseas-born women, based on their PDC record. For Indigenous status, we enhanced reporting in the PDC by linkage to other PDC records.18 Records with missing country of birth data (2090 records, 0.4% of all records) were placed in the “born overseas” category.

We calculated crude HBV prevalence for the four maternal year-of-birth categories, and used logistic regression to examine the relationship between these categories and HBV infection. We adjusted analyses for year of giving birth (in 5-year intervals) to account for possible temporal trends in HBV prevalence,2 and for the mother’s area of residence (two categories, based on residential postcode in the PDC record: major cities and regional/remote, according to the Accessibility/Remoteness Index of Australia19), as HBV prevalence in Australia varies between regions.3 The two most recent maternal year-of-birth categories (1988–1991, 1992–1999) were combined (1988–1999) for the logistic regression analysis because the numbers of records in the individual groups were small.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the NSW Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee (reference, 2009/11/193) and the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council Human Research Ethics Committee (reference, 841/12).

Results

Between January 2000 and December 2012, 482 998 women residing in NSW gave birth to their first child (PDC data); 54 were linked to an acute HBV notification and excluded from further analysis. Of the remaining 482 944 records, 11 738 (2.4%) were Indigenous Australian women, 319 629 (66.2%) were non-Indigenous Australian-born women, and 151 577 (31.4%) were born overseas. A linked unspecified HBV notification before the date of birth of their first child was available for 3383 women (HBV prevalence, 0.70%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.68–0.72%). HBV prevalence was estimated as 0.79% (95% CI, 0.63–0.95%) for Indigenous Australian women, 0.11% (95% CI, 0.09–0.12%) for non-Indigenous Australian-born women, and 1.95% (95% CI, 1.88–2.02%) for overseas-born women.

For Indigenous Australian women, the prevalence of HBV infection was significantly lower for those who were eligible for universal school-based or at-risk newborn vaccination (born between 1992 and 1999) than for women born during the pre-vaccination period (≤ 1981): 0.15% (95% CI, 0.00–0.35%) v 1.31% (95% CI, 0.91–1.71%; for trend, P < 0.001). For non-Indigenous Australian-born women, the prevalence also declined, but the fall was not statistically significant: from 0.10% (95% CI, 0.09–0.11%) to 0.04% (95% CI, 0.00–0.09%; for trend, P = 0.5). There was no significant trend for overseas-born women between the two periods (P = 0.1) (Box 1, online Appendix 2).

In analyses adjusted for year of giving birth and region of residence (Box 2), the proportion of Indigenous Australian women notified as having an HBV infection was 80% lower for those eligible for vaccination as part of the at-risk infant or universal school-based vaccination programs (born 1988–1999) than for women born during the pre-vaccination period (1981 or earlier) (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.20; 95% CI, 0.09–0.48). There was no significant change for non-Indigenous Australian-born women (aOR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.54–1.44). For overseas-born women, the number of notifications was significantly higher for women born during 1988–1999 than for those born before 1981 (aOR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.15–1.67).

Box 2 also shows that HBV notifications were more frequent for Indigenous women living in regional and remote areas than for those in major cities (aOR, 2.23; 95% CI, 1.40–3.57). The opposite applied to non-Indigenous Australian-born (aOR, 0.39, 95% CI, 0.28–0.55) and overseas-born women (aOR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.49–0.77).

The study timeframe and inclusion criteria (first births during 2000–2012) meant that the mean age of mothers was lower in later than in earlier birth year groups. After adjusting for maternal birth year groups, a significant decline in HBV notifications among Indigenous women of about 30% was still detected (aOR for each 5-year period, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.49–0.97; P = 0.03). A decline for overseas-born women was also found, but it was much smaller (aOR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.84–0.93; P < 0.001), and there was no change for non-Indigenous Australian-born women (aOR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.84–1.16; P = 0.90; Box 2).

To further explore the changes in HBV prevalence in overseas-born women, HBV notifications were also analysed by maternal year of birth and region of birth (Box 3). The highest proportions of women with HBV notifications were for those born in North-East Asia, South-East Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa. The small sample sizes made comparisons of trends across maternal year of birth less robust, but a consistent increase in HBV notification rates was observed for women born in North-East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (for each trend, P < 0.001).

Discussion

This is the largest study to examine differences in HBV notification rates for women born before and after the introduction of HBV vaccination programs in Australia, analysed by country of birth, Indigenous status, and region of residence. We found that HBV notification rates for Indigenous women born after the introduction of targeted infant HBV vaccination were 80% lower than for those born earlier. For non-Indigenous Australian-born and overseas-born women there were no consistent associations between HBV notification rates and HBV vaccination programs in NSW. Despite limited data about the level of HBV vaccination coverage achieved when the at-risk newborn vaccination program was introduced in NSW in 1987, our findings suggest that it was highly successful. The estimates of HBV notification rates in Indigenous women were substantially lower among those born after 1987 than among women born before the start of the program (Box 1). It is notable that the 80% decline we report matches the 79% reduction found by a study that compared Indigenous women in the Northern Territory born before and after the introduction of universal newborn vaccination,2 suggesting that the targeted program was highly effective in reaching those at risk. The estimated fall is also similar to the results of investigations in other countries of the impact of universal newborn vaccination programs.20,21

A lack of consistent trend in HBV notifications among non-Indigenous Australian-born women might be expected, as the notification rate in this population before the introduction of vaccination was considerably lower than for Indigenous women. Further, most non-Indigenous women born during 1988–1999 would have been eligible only for school-based catch-up vaccination, which is less effective in preventing chronic disease than infant vaccination. Interpreting the relationship between birth cohorts and HBV prevalence in overseas-born women was complicated by a number of factors, including the differing prevalence of HBV in the regions from which overseas-born women migrated, their age at migration, and the lack of information about receipt of vaccination in their country of origin. When analysed by region of origin, the observed changes in notification rates could reflect either varying local uptake of infant HBV vaccination or differences in the populations that have migrated to Australia from particular regions over the 13-year study period. The smaller numbers of women involved in each group, however, limit our ability to draw conclusions.

Regional differences in HBV prevalence were also observed. Indigenous Australian women in regional and remote NSW were more likely to be HBV-seropositive than those in urban areas, whereas the reverse was true for non-Indigenous Australian-born and overseas-born women. These differences in HBV prevalence have been described previously in Indigenous Australians,2 but the reasons underlying them are unclear. The colonisation process and the institutional racial discrimination that Indigenous Australians experience affect their health outcomes, mediated by a number of different pathways, including unequal access to health care, housing and employment.22,23 As access to primary health care services relative to need is lowest in remote areas, and proportionately more Indigenous than non-Indigenous Australians live in remote areas,24 these factors may contribute to higher HBV prevalence among Indigenous women in rural and remote areas. In addition, an uncommon, more virulent HBV subgenotype circulates among Indigenous Australians in the NT, perhaps reducing the efficacy of vaccination;25 the distribution of this subgenotype in NSW, however, is unknown.

The higher prevalence of HBV among urban than regional non-Indigenous women may be related to the higher proportions of women in cities who inject drugs or are in prison, both risk factors for acute HBV infection.26 For women born overseas, the difference might be related to the fact that a greater proportion of migrants from high HBV prevalence countries (such as Asia) reside in urban than in regional and remote areas (online Appendix 3).27

It was not possible in our ecological study to take into account interactions between the effects of age and calendar year on HBV notification. Women who were born more recently, and therefore more likely to have been vaccinated, would have been younger at the time of our linkage, but also potentially subject to different risks of exposure at a given age. Including the year a woman gave birth as a factor in the regression model for Indigenous Australian women led to a small reduction in the effect of maternal birth year on HBV prevalence, and HBV prevalence was lower for more recent year of giving birth, after adjusting for maternal year of birth (Box 2). This suggests that temporal trends other than the effect of maternal birth year may have contributed to the decline in HBV notifications for Indigenous Australian women, although residual confounding related to inadequate adjustment for maternal birth year effects cannot be excluded. A similar trend, but of smaller magnitude, was seen among overseas-born women.

Antenatal screening for HBV infection enabled us to systematically assess HBV prevalence in a large population of women. Study limitations include our focus on women giving birth; our conclusions may not be generalisable to other women or to men, but we expect that the overall trends would be similar. We were unable to assess the impact of universal newborn vaccination on HBV notifications, as no women born after 2000 had given birth during the study period. Further, the ecological nature of our analyses depended on assumptions about the exposure of individuals to different vaccination strategies according to year of birth, whereas individual level vaccination data would assist us more reliably quantify their effects. Interpreting changes in HBV prevalence by country or region of birth was further limited by a lack of information about when women migrated to Australia. Some HBV notifications classified as “unspecified” may actually have been acute infections, but their frequency should not have differed between maternal birth year groups, and would therefore not have affected our estimates of HBV prevalence. Finally, linkage errors are possible, but their rate is known to be low.

Conclusion

Analysing routine antenatal HBV screening data is a simple and cost-effective method for monitoring changes in HBV prevalence in both the general population and in some high risk populations. The newborn and childhood HBV vaccination programs in NSW have had a significant impact on HBV prevalence in Indigenous Australian women, but it is still substantially higher than among non-Indigenous women. HBV infection prevention programs for high risk groups should be targeted differently, with those for Indigenous Australians focused on regional and remote NSW, and those for migrant populations on major cities. Finally, our analysis could be repeated periodically to assess the ongoing impact of universal newborn HBV vaccination and future targeted programs on HBV prevalence in Australia.

Box 1 –

Hepatitis B notifications for primiparous women giving birth, by maternal birth year, New South Wales, 2000–2012

Box 2 –

Association between HBV notifications* and maternal year of birth, year of giving birth, and region of residence

|

|

Median age (years)

|

Number of women

|

Univariate analysis

|

Multivariate analysis

|

|

Giving birth

|

Giving birth, with HBV record

|

Odds ratio (95% CI)

|

P†

|

Adjusted odds ratio (95% CI)‡

|

P†

|

|

|

Australian-born women, Indigenous

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Maternal year of birth

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

≤ 1981

|

27.4

|

3057

|

40 (1.3%)

|

1

|

< 0.001

|

1

|

0.002

|

|

1982–1987

|

20.8

|

4509

|

45 (1.0%)

|

0.76 (0.50–1.17)

|

|

0.79 (0.51–1.23)

|

|

|

1988–1999

|

18.8

|

4172

|

8 (0.2%)

|

0.15 (0.07–0.31)

|

|

0.20 (0.09–0.48)

|

|

|

Region of residence

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Major cities

|

|

4916

|

24 (0.5%)

|

1

|

0.002

|

1

|

< 0.001

|

|

Regional/remote

|

|

6752

|

69 (1.0%)

|

2.08 (1.31–3.32)

|

|

2.23 (1.40–3.57)

|

|

|

Year of giving birth (per 5 years)

|

|

|

|

0.45 (0.34–0.61)

|

|

0.69 (0.49–0.97)

|

0.03

|

|

Australian-born women, non-Indigenous

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Maternal year of birth

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

≤ 1981

|

30.7

|

227 608

|

227 (0.1%)

|

1

|

0.50

|

1

|

0.10

|

|

1982–1987

|

23.6

|

67 762

|

91 (0.1%)

|

1.35 (1.06–1.72)

|

|

1.47 (1.14–1.91)

|

|

|

1988–1999

|

19.9

|

24 259

|

18 (0.1%)

|

0.74 (0.46–1.20)

|

|

0.87 (0.54–1.44)

|

|

|

Region of residence

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Major cities

|

|

242 392

|

298 (0.1%)

|

1

|

< 0.001

|

1

|

< 0.001

|

|

Regional/remote

|

|

77 195

|

38 (0.0%)

|

0.40 (0.29–0.56)

|

|

0.39 (0.28–0.55)

|

|

|

Year of giving birth (per 5 years)

|

|

|

|

1.04 (0.90–1.20)

|

|

0.99 (0.84–1.16)

|

0.90

|

|

Overseas-born women

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Maternal year of birth

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

≤ 1981

|

31.7

|

116 659

|

2245 (1.9%)

|

1

|

0.10

|

1

|

0.001

|

|

1982–1987

|

25.2

|

29 431

|

580 (2.0%)

|

1.03 (0.93–1.12)

|

|

1.11 (1.01–1.22)

|

|

|

1988–1999

|

20.9

|

5487

|

129 (2.4%)

|

1.23 (1.03–1.47)

|

|

1.38 (1.15–1.67)

|

|

|

Region of residence

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Major cities

|

|

144 926

|

2872 (2.0%)

|

1

|

< 0.001

|

1

|

< 0.001

|

|

Regional/remote

|

|

6621

|

82 (1.2%)

|

0.62 (0.50–0.77)

|

|

0.61 (0.49–0.77)

|

|

|

Year of giving birth (per 5 years)

|

|

|

|

0.92 (0.88–0.96)

|

|

0.89 (0.84–0.93)

|

< 0.001

|

|

|

* For the purposes of our analysis: defined as a record in the NSW Notifiable Conditions Information Management System of the detection of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) between January 1994 and December 2012 with the infection classified as being of unspecified duration (or not newly acquired). † For trend across categories of maternal birth year, calculated using the median maternal year of birth in each category. ‡ Adjusted for maternal year of birth, region of residence, and year of giving birth (5-year intervals).

|

Box 3 –

HBV notifications for non-Australian-born women giving birth for the first time, by region of birth

|

Mother’s region of birth

|

Maternal year of birth

|

|

≤ 1981

|

1982–1987

|

1988–1999

|

|

Number of women

|

Proportion with HBV record (95% CI)

|

Number of women

|

Proportion with HBV record (95% CI)

|

Number of women

|

Proportion with HBV record (95% CI)

|

|

|

North-East Asia

|

21 159

|

4.4% (4.2–4.7%)

|

4455

|

5.4% (4.7–6.1%)

|

583

|

11.2% (8.8–14.0%)

|

|

South-East Asia

|

22 824

|

4.3% (4.2–4.7%)

|

4596

|

4.5% (4.0–5.2%)

|

680

|

4.1% (2.9–5.9%)

|

|

Oceania (excluding Australia)

|

12 124

|

1.1% (0.9–1.2%)

|

3335

|

1.0% (0.7–1.4%)

|

1260

|

0.7% (0.4–1.4%)

|

|

Sub-Saharan Africa

|

4409

|

0.9% (0.6–1.2%)

|

965

|

3.0% (2.1–4.3%)

|

244

|

4.9% (2.8–8.4%)

|

|

North Africa or Middle East

|

9064

|

0.6% (0.5–0.8%)

|

4592

|

0.5% (0.3–0.8%)

|

1368

|

0.9% (0.5–1.5%)

|

|

South or Central Asia

|

12 268

|

0.3% (0.3–0.5%)

|

7292

|

0.4% (0.3–0.6%)

|

831

|

0.2% (0.1–0.9%)

|

|

Europe

|

25 899

|

0.2% (0.1–0.2%)

|

2764

|

0.4% (0.3–0.8%)

|

303

|

0.3% (0.1–1.9%)

|

|

Americas

|

7262

|

0.04% (0.0–0.1%)

|

1084

|

0.3% (0.1–0.8%)

|

126

|

0.0% (0.0–3.0%)

|

|

Other

|

1650

|

0.6% (0.3–1.0%)

|

348

|

0.9% (0.3–2.5%)

|

92

|

0.0% (0.0–4.0%)

|

|

|

|

more_vert

more_vert