Preventive health assessments have become a feature of health policies internationally.1 In Australia, Medicare-funded Indigenous-specific health assessments (herein referred to as “health assessment”) and follow-up items have been progressively introduced since 1999 as a means to improve the limited preventive health opportunities and reduce high rates of undetected risk factors among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (respectfully referred to hereafter as Indigenous people) (Box 1).3,4

A recent systematic review shows that while health assessments may increase new diagnoses, there is a lack of evidence of their effect on morbidity and mortality.1 While the reasons for lack of impact of health assessments are not well understood, it is clear that health assessments have limited potential to impact on health outcomes in the absence of appropriate follow-up care.5–7 The $805 million Indigenous Chronic Disease Package (ICDP) introduced by the Australian Government in 2010 included program funding and a new workforce to help increase the delivery of health assessments and appropriate follow-up.8

Analysis of Medicare data shows an increase in the uptake of health assessments, but relatively limited billing for Indigenous-specific follow-up items.5,9 The limited use of follow-up items raises questions about the effectiveness of health assessments as a catalyst for enhancing access to preventive care and chronic disease management,10,11 and highlights the need for further research on how to increase follow-up after a health assessment.12

This paper reports on patterns of uptake of health assessments and associated follow-up items, and examines the barriers and enablers to delivery and billing of follow-up care over the first 3 years of implementation of the ICDP.

Methods

The analysis presented here draws on the mixed-methods Sentinel Sites Evaluation (SSE) of the ICDP. SSE methods are detailed elsewhere.5 The SSE was a formative evaluation covering 24 urban, regional and remote locations in all Australian states and territories. Data were collected, analysed and reported in 6-monthly intervals over five evaluation cycles between 2010 and 2012.

Data on uptake of health assessments and follow-up items were derived from administrative billing data provided by the Department of Health from 1 May 2009 to 30 May 2012. The period May 2009 to April 2010 was used as a “baseline” period, as it preceded implementation of the ICDP. Health assessment data include Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) items, and are presented as health assessments claimed by services within the site boundaries per 100 Indigenous people aged ≥ 15 years. Similarly, the follow-up data include MBS items for follow-up of health assessments (see Box 1 for health assessment and follow-up items included in this analysis). Population data are based on Australian Bureau of Statistics projections from the 2006 Census according to the statistical boundaries used to define the sites.

Qualitative data on barriers and enablers to delivery of and billing for follow-up were obtained from individual and group interviews with a range of key informants from Aboriginal Health Services (AHSs), which include community controlled and government managed health services, and the general practice sector, which includes employees of Medicare Locals and general practices (Appendix 1). Interviewees were purposively sampled for their knowledge and experience with the ICDP. Interviews and analysis were informed by data on state of implementation of the ICDP at site level, as reflected in Department of Health reports. Repeated 6-monthly cycles of interviews and feedback of data between 1 November 2010 and 30 December 2012 allowed review and refinement of our understanding of delivery and billing of health assessments and follow-up items.

Community focus groups were conducted to explore community perceptions of accessibility and quality of services. Data from community focus groups were related to access to health services in general rather than being specific to follow-up of health assessments.

For the purposes of this paper, we conducted an analysis of SSE data using a socioecological framework.13,14 We reviewed the themes that were identified through the SSE as barriers and enablers to follow-up of health assessments,5 and used an iterative approach to categorise these themes according to various levels of influence: patient, patient–health service relationship, health service or organisation, community and policy environment. Some themes could be interpreted as a barrier or an enabler, and some were relevant to more than one level. We have therefore described each theme according to the predominant direction and most important level(s) of influence.

Ethics approval for the SSE was granted through the Department of Health Human Research Ethics Committee, project 10/2012.

Results

Of the 581 individual interviews done through the SSE, 63 contained specific information about the follow-up of health assessments. Of the 58 group interviews, 31 contained information relevant to this paper. These 31 group interviews included 103 participants. Of the 72 community focus groups, 69 provided data on access to services (Appendix 1).

Uptake of Indigenous-specific health assessments and follow-up Medicare items

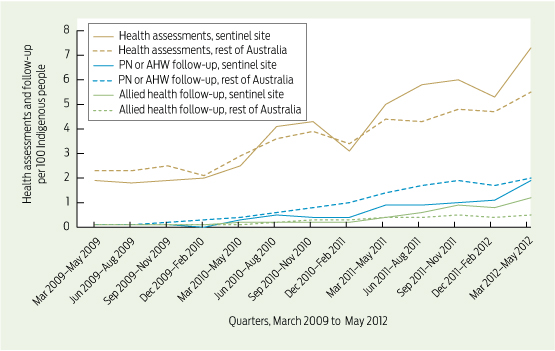

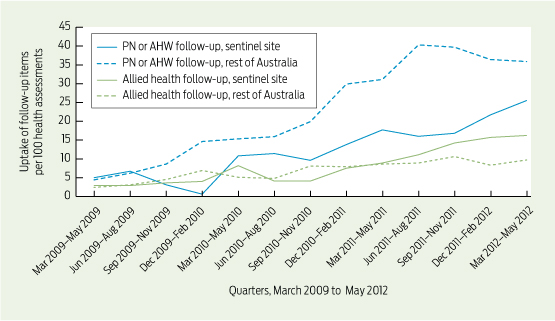

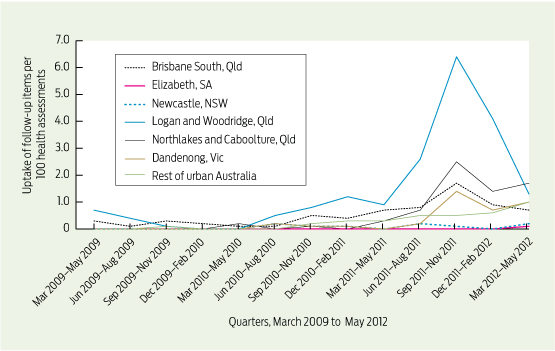

Aggregated data show a general improvement in uptake of health assessments and follow-up items after the baseline period, with some differences in trends between the sentinel sites and the rest of Australia (Box 2 and Box 3). The uptake of follow-up items was disproportionately low compared with health assessments. There were marked differences in trends between individual sites (Box 4) — more marked than differences between sites according to rurality.5

Levels of influence

Barriers and enablers to delivery and billing of follow-up care using a socioecological framework were identified at five levels of influence: patient, interpersonal, health service, community and policy. Findings at each level of influence are summarised below and exemplar quotes illustrating each theme and sub-theme are provided in Appendix 2.

Patient level

Strategies to create community demand and incentives for patients to undergo health assessments were evident at the local level. These strategies did not appear to include attention to increasing follow-up of health assessments, and there was little evidence of patient demand for follow-up after health assessments in the sentinel sites overall. People working in ICDP-funded support roles with responsibility for encouraging patients to attend for follow-up reported that patients frequently appeared to lack information about the reasons for their follow-up referrals.

Interviewees in some sites identified relatively frequent movement of people, with no regular residential address and limited options for contacting patients by phone, as constraining follow-up care. Limited access to transport was consistently identified by community focus groups as a barrier to accessing services. Concerns were expressed about the cost of accessing follow-up services, with out-of-pocket costs to patients for allied health care in particular being unpredictable.

Interpersonal level

Negative past experiences affected patients’ willingness to attend follow-up appointments. Community focus groups and interviewees shared personal stories that reflected perceptions of racist attitudes among health service staff — commonly reception staff.

Outreach workers, funded through the ICDP, played a key role in educating and supporting allied health providers and clinicians to provide culturally appropriate care in isolated pockets, but overall, allied health professionals had relatively limited access to cultural awareness training. General practitioners and practice staff were reluctant to refer patients to allied health professionals who they could not be confident would act in a culturally appropriate way.

Some GPs reported reluctance to refer patients for follow-up unless critical because they believed the patient would not attend, or they provided referrals with no expectation of attendance. Some patients appeared to resist adherence to follow-up referrals and treatment due to what they regarded as the “pushy” nature and communication style of some health professionals, and lack of adequate explanation of their health problem and treatment needs.

External support by regional support organisations including Divisions of General Practice (and subsequently Medicare Locals) helped improve awareness of the Indigenous-specific follow-up item numbers in health services and among allied health providers.

Health service level

Health service providers felt that short consultation times meant they had limited opportunity to explain reasons for referral for follow-up care to patients. This was related in part to shortage of service providers, including GPs, allied health professionals, Aboriginal Health Workers (AHWs) and practice nurses. Limited numbers of allied health professionals in particular constrained referral for allied health services. In some settings, eligibility requirements meant that some AHWs appeared to be ineligible to bill for relevant follow-up services, constraining use of these item numbers.

Organisations tended to have a greater focus on health assessments — partly for financial reasons rather than potential health benefit — with less attention to follow-up. This imbalance was also evident at policy and patient levels. Small numbers of Indigenous patients in many general and allied health professional practices were associated with a reluctance to reorient systems to address the needs of relatively few patients.

A general orientation within some health services to acute rather than chronic illness care limited the availability and interest of many nurses in providing follow-up services. This was particularly the case in remote settings, where acute care skills are an important criterion in recruiting nurses. GP-centric models of care, lack of clarity about roles and lack of confidence in co-workers were associated with limited opportunities for practice nurses and AHWs to manage patient lists and appointments and deliver follow-up consultations.

Another constraint on the uptake of follow-up items was the lack of established systems to organise and bill for follow-up, and a perception that the steps required for completion and correct billing of follow-up services were complex and required highly organised patient records and information flow. The need for changed work patterns, reorientation to preventive health and enhanced staff training and support in the use of clinical information systems presented significant challenges to health services in delivering and claiming these Medicare items. Leadership and management were vital to system change: where leadership lacked commitment, management practices did not support system change to implement this aspect of the ICDP. Where GP-centric models of care were entrenched, it was particularly difficult to reorient systems to enhance uptake of follow-up items.

Lack of capability in using clinical information systems, such as patient recall and reminder systems, also constrained follow-up. Ineffective use of these systems to support patient care was commonly reported in AHSs and general practices, and was also evident in allied health professionals’ practice systems.

Staff turnover and use of locum staff (both nursing and GP) were associated with limited use of follow-up items. GPs were found to have varying knowledge and skills in relation to accessing appropriate Medicare items and working within a multidisciplinary team. Fluctuating staff numbers and variable knowledge among staff of the service operations made it difficult to reorganise systems to enhance follow-up.

Interviewees commonly reported that follow-up consultations were frequently billed as a standard consultation rather than the correct Indigenous-specific Medicare item number.

Lack of private allied health providers, and a tendency — for cost reasons — for clinicians to refer to salaried allied health professionals, where these professionals were available, also limited the use of the Medicare follow-up item numbers. Lack of easy access to information and transparency around gap payments, and entrenched perceptions that services would be expensive and require numerous repeat visits, were a barrier to health service staff referring patients to allied health professionals.

Community level

Barriers related to Indigenous social and economic disadvantage included poor availability of transport to attend follow-up appointments and high or unpredictable cost of allied health services. These were exacerbated in the context of general social and financial disadvantage. ICDP-funded outreach workers played an important role in helping patients overcome transport barriers in some sites.

Policy level

At the policy level, the relatively low value of the MBS reimbursement for follow-up (relative to health assessment), reflected in the large gap payments that patients are faced with, appears to be an important constraint to greater uptake of the financial incentives available for follow-up. Increased and ongoing funding to support preventive care through Medicare encouraged uptake of follow-up care. The impact of this was constrained by relative emphasis on health assessments. There was confusion over eligibility of AHWs to claim the use of the follow-up items. Funding of positions and programs (including through the ICDP) to assist with provision of information to providers and community members and to overcome barriers to access enabled uptake of follow-up items.

Discussion

While there has been a substantial increase in the uptake of health assessments over recent years, delivery of follow-up care and billing for Medicare Indigenous-specific follow-up items was disproportionately low, particularly given the evidence of the high levels of need for follow-up.6,12,15,16 Our study identified multiple influences on uptake of follow-up care at various levels of the system — many related to actual delivery of follow-up care and some related to billing for Medicare items numbers. The influences identified in our analysis are consistent with the research on barriers to implementing health assessments and on access to health services more generally.3,6,7,17–19 It appears that people receiving health assessments may be those who use health services more frequently,5 those of higher socioeconomic status, those with lower rates of morbidity and mortality and those with lower risk of chronic disease.1,20 Thus, health assessments may not be reaching those who need them most, reducing potential benefits at a population level. This “inverse care law”21 is likely to also be relevant to follow-up of health assessments, indicated by the access and cost barriers to follow-up identified in this analysis.

Strengths of the analysis in this paper include the mixed-methods approach, numbers and diversity of interviewees, geographic scope and diversity of study sites, and long-term repeated engagement with stakeholders, including feedback and member-checking of data and interpretation by local stakeholders. The socioecological analytical framework highlights that there are a number of factors at different levels of the system that enable or constrain choices made by individuals about access to health care.13,14

Limitations of this study include that sites were selected on the basis of early and relatively intense ICDP investment, and interviewees were selected because of their knowledge and interest in Indigenous health. The data provide a broad perspective of service settings across Australia, but this perspective may not necessarily be representative. Other limitations include that administrative data reflect billing for Medicare items, but do not necessarily accurately reflect the provision of clinical care. There is some evidence that follow-up may be happening, but that it is not being billed accurately. However, many of the identified barriers related to delivery of follow-up care rather than billing for follow-up items. Ecological models require themes to be categorised, and this process may be overly Western-centric.22 In conducting the analysis our team (which included Indigenous members) was sensitive to this risk. The strong links and interrelationships between themes need to be recognised. More general limitations of the SSE have been described elsewhere.5

Overcoming barriers to follow-up and strengthening enablers is vital to achieving health benefits from the large financial and human resource investment in health assessments. Our findings point to the need to support health services in developing systems and organisational capability to undertake follow-up of health assessments, but more importantly to reorient to high-quality, population-based and patient-centred chronic illness care. Drawing on our findings, we propose actions at various levels of the system to enhance both delivery of follow-up care and billing for follow-up items (Box 5). The diversity of contexts in which health services operate, the wide variation in current levels of follow-up between sites and the relevance of different contextual factors to barriers to uptake in different sites mean that strategies will need to be tailored to local circumstances.

1 Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS)-rebated items for Indigenous-specific health assessments and follow-up2

|

Item characteristic

|

Health assessment

|

Follow-up by a PN or registered AHW

|

Follow-up by an allied health professional

|

|

|

Description

|

Available to all Indigenous people and may only be claimed by a general practitioner

|

After a health assessment, a follow-up item can be claimed by GPs for follow-up services delivered by a PN or registered AHW on behalf of the GP

|

After a health assessment, if the GP identifies a need for follow-up by an allied health professional, a referral is made and the allied health professional can claim this item

|

|

MBS item number

|

704, 706, 710 to 1 May 2010; thereafter 715

|

10987

|

81300–81360

|

|

MBS rebate

|

$208.10

|

$24.00

|

$52.95

|

|

Notes

|

Changed to simplify claiming by streamlining MBS item numbers to one item and making all claimable annually. This came into effect from May 2010 and coincided with implementation of the ICDP

|

Introduced in 2008, this MBS item allowed five follow-up services per patient per calendar year. This was expanded in 2009 to allow 10 follow-up services per patient per calendar year

|

Introduced in 2008, on referral from a GP, a maximum of five follow-up allied health services per patient per calendar can be claimed

|

|

|

AHW = Aboriginal Health Worker. ICDP = Indigenous Chronic Disease Package. PN = practice nurse.

|

2 Health assessments provided by a general practitioner, and follow-up services provided by a practice nurse (PN), registered Aboriginal Health Worker (AHW) or allied health professional

3 Follow-up services provided by a practice nurse (PN), registered Aboriginal Health Worker (AHW) or allied health professional in Indigenous people who had a health assessment

4 Uptake of practice nurse (PN), registered Aboriginal Health Worker (AHW) or allied health professional follow-up items in all urban sentinel sites and in the rest of urban Australia

5 Potential strategies for strengthening follow-up of health assessments

Approaches to enhancing follow-up are presented for each level of the socioecological model. It is important that strategies to enhance follow-up use approaches across the range of levels, with attention to maximising synergies between approaches at different levels.

Patient level

- develop locally relevant evidence-based approaches to create community demand for follow-up of adult health assessments;

- address transport and other barriers to access to follow-up care; and

- strengthen linkages between health services and local communities to enable recall of patients who require follow-up.

Interpersonal level

- ensure that cultural awareness training reaches relevant providers, including allied health professionals and service support staff, such as receptionists.

Health service level

- continue efforts to raise awareness of the follow-up Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) item numbers among health service staff and allied health professionals, including how item numbers complement each other and why the correct Indigenous-specific item numbers should be used (eg, additional numbers of items available with specific item numbers);

- strengthen capability of health service staff to make effective and efficient use of clinical information systems, specifically including use of recall and reminder systems. Ongoing training and workforce development is required to address staff turnover and locum staff needs;

- support service reorientation from models suited to acute care to models suited to patient-centred and long-term care;

- develop and assess effectiveness and efficiency of alternate models of provision of allied health services and “what works for whom and in what circumstances”; and

- identify and communicate cost implications of referral for follow-up care, and address cost barriers to follow-up care.

Community level

- raise awareness of the need for ongoing chronic illness care and the importance of follow-up of issues identified in health assessments; and

- identify relatively high-need and hard-to-reach groups in local communities, and develop strategies to overcome the barriers to these groups accessing follow-up care.

Policy level

- clarify the Aboriginal Health Worker role in provision of services, including provider number eligibility;

- ensure that the policy intent of having an Indigenous-specific MBS item number for follow-up services is clearly understood at different levels in the system; and

- emphasise the health-relevance of health assessments and the importance of follow-up care, and refine incentives to maximise potential health gain.

more_vert

more_vert