The report of the 2015 Lancet Commission on Health and Climate Change1 is timely and welcome, particularly because of the emphasis on the health benefits of transition to sustainable ways of living. However, there is little in the report on the potential role of indigenous and local knowledge in both adaptation and mitigation responses for human health. This lack of attention is not confined to the health sector, and has been observed in other societal sectors that are the target of adaptation and mitigation efforts.

Preference: Indigenous Health

1

Building on the rich heritage of the Medical Journal of Australia

My professional interests span clinical practice, medical education and research, medical leadership, health policy and social justice. My goals as editor are to build on the outstanding DNA of the Journal, further increasing its relevance and readability, and attracting the highest quality submissions. We will aim to build on the Journal’s rich heritage by continuing our practice of publishing the best clinical science papers that have the potential to transform practice, including clinical trials and comparative effectiveness research. We will also aim to inform readers on advances in medical education, and cover issues from medical leadership to re-engineering our health system. We will continue to seek expert reviews, editorials and commentaries, meta-analyses and guidelines, and the latest news and information that everyone in practice needs to know. It is my goal to reinforce the unique role that the Journal plays as the pre-eminent publisher of Australian medical research and as a vital platform for translating research into practice, as well as helping to inform the broader health policy debate. This is part of the Journal’s success and why it is relevant to clinicians, researchers and academics across the nation.

The MJA is prestigious and influential, but another advantage to publishing with us is that much of the content including our research content is published freely on our website at mja.com.au, without the waiting period often imposed by other journals. I can also assure readers that as Editor-in-Chief, I have a guarantee of editorial independence and I will fiercely guard this independence on your behalf. For the nearly 32 000 subscribers who receive the MJA in print, and the many others who read the Journal online, the team will work tirelessly to provide the best medical journal experience possible.

We live in a world that, in terms of connectivity through social media, is rapidly shrinking, and the MJA has an important role to play not just nationally but globally. We will therefore now be encouraging locally relevant international articles. And we will continue to tackle in our pages articles that highlight the tough health issues we all face and provide possible solutions, from the health needs of Indigenous Australians to the health impacts of global migration, population growth, dwindling resources, an ageing population and climate change, to name a few. We will look both out to the world and across Australia to find the objective data that can help guide us all. We will seek balance among the many expert opinions and will aim at all times to be rigorous, evidence-based and transparent.

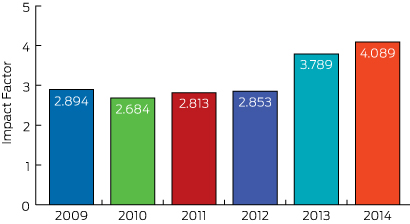

Whether any of us like it or not, our performance in medicine is being increasingly measured and critiqued, and it’s no different for medical journals. Clinicians and academics want to publish in the best medical journals and one metric applied universally is the impact factor, calculated by counting the mean number of citations received per article published during the previous 2 years. In the best journals, editors arguably “live and die” by the journal impact factor published each year. The impact factor is flawed (some argue fatally so) and is not used by the National Health and Medical Research Council; but it can’t be ignored either!1,2 In 2015, the MJA, your national journal, ranks in the top 20 general medical journals worldwide and has a highly respectable impact factor of 4.089 (Box, previous page). I am pleased to say that the impact factor of the MJA has risen and I anticipate over the coming years that it will continue to rise (as will other metrics of excellence) as we further increase the quality and reach of what we publish.

We welcome your best work being submitted for consideration. Our acceptance rate is currently falling (as marks all of the best medical journals) but I can pledge that your medical articles will be expertly peer reviewed and edited before publication. The editorial team will do its utmost to ensure it makes the best possible decisions, and we will work hard with authors to help them publish polished, excellent contributions.

Finally I would like to acknowledge and thank Professor Charles Guest in his capacity as Interim Editor-in-Chief for his stewardship of the Journal in the second half of 2015. He has been instrumental in supporting our editors and maintaining the continuity and the quality of the Journal.

Thank you for reading the MJA. You can expect that the Journal will be further increasing its scientific reputation and international presence over the next few years, and I hope you will be part of it if you have a contribution you wish to make. We welcome suggestions and feedback so we can further improve the Journal on your behalf. I am committed to strengthening your clinical practice through its pages and look forward to our journey together.

Red Dust, dingoes, trauma and Sepsis

Dr Chris Edwards of EMJourney recounts his time as a remote retrieval registrar based in Alice Springs. Follow him on twitter @EMtraveller

I’ve had the privilege to work as a Retrieval Registrar for the Alice Springs Hospital Retrieval Service in Central Australia for the last 6 months. How to describe it – words that spring to mind include:

- Challenging (unlike many other retrieval jobs, you often are intimately involved in the logistics planning)

- Satisfying (providing ICU level care to the most remote parts of Australia)

- Scary (providing ICU level care to the most remote parts of Australia!)

- Clinical character forming (Brown underpants occasionally needed)

- Interesting (When a potassium > 7 and severe rheumatic heart disease no longer turns your head)

- Scenic (people pay money to see Uluru from the air, I get paid)

The Central Australian Retrieval service retrieves patients mainly by fixed wing aircraft over a catchment area of 1.6 million square km. We also perform inter-hospital transfers to Adelaide and Darwin (that’s 3.5 hours, one way, either way!) Let me try to put the sheer size of our catchment area and distance from our tertiary referral centres into perspective…

Here is Australia, our tertiary referral centres and our catchment area roughly outlined…

I think you get the idea – this is a huge catchment area! With one other small hospital in Tennant Creek, the rest of our primary retrievals are to remote health clinics, staffed by RANs (Remote Area Nurses).

In our primary retrieval we don’t have sub-specialty retrieval teams so we do it all, although we do occasionally take a paediatrician with us. Common conditions, mostly from our indigenous population but occasionally a grey nomad or overly adventurous backpacker, include:

- Trauma (usually penetrating or MVA)

- Sepsis (and sometimes overwhelming septic shock)

- Snake bites/stick bites

- Renal disease – Missed dialysis with APO and/or hyperkalaemia

- Threatened/established/imminent/delivered labours at term/pre-term (I mentioned the brown underpants right?)

- Paediatrics – URTIs, LRTIs, infected scabies, post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis

Mostly our patient population is young, less than 50 years old – I haven’t retrieved a single NOF fracture since I got here!

Then there’s the inter-hospital retrievals; Mostly to Adelaide, we take intubated patients on inotropes, trauma patients with chest drains and vacmat with spinal precautions, recently lysed STEMIs, including failed thrombolysis with ongoing arrhythmia for rescue PCI (52 shocks is my current record); I’ve even taken two patients so far with intra-cranial bleeds and extra-ventricular drains (first time I had even seen one).

Equipment and Staff

The plane we use is the Pilatus PC-12, a single-engine turboprop made by the Swiss. It has a cruising speed of approximately 500km/hr and a maximum service ceiling of 30,000ft with cabin pressurization of <8000ft. We operate with a single pilot and flight nurse. The passenger cabin is modified to carry two stretchers and 3 seats. The plane also comes with a hydraulic stretcher loader in the rear exit – maximum load of 182kg. The PC-12 is ideal for our environment – it can land on shorter strips and can be flown with only one pilot – keeping our take-off and landing weights down.

Interior of the PC-12

On the plane, we carry the doctor’s bag, which contains central lines, arterial lines, fast trach intubating LMAs, rapid infusion catheters, EZ-IO, scalpels, bougies and other useful gear. We also have onboard a standalone intubation kit, cannulation kit, equipment for infusions, syringe drivers, pump sets, a full cold and warm drug box, an Oxylog 3000, a Zoll X-series monitor/defibrillator/pacer and of course the most important – coffee/tea bag. Additional equipment we can carry includes a maternity pack, trauma pack, neonatal pack, a vacmat, a humidicrib, paediatric ventilator, surfactant, a Sonosite M-Turbo and 2-4 units of packed RBCs.

Our Flight Nurses are the backbone of the clinical service. Trained in both critical care and midwifery they have a broad skill set and a lot of experience. They have invaluable clinical and logistical knowledge and when it comes to obstetric cases, my general approach is to ‘Remain Above The Navel’ and do what I’m told!

The Retrieval Doctors have a varied background – some are Rural and Remote Medicine trained, some are budding intensivists, but the majority are Emergency trainees. What we all need to have in common is the ability to be flexible and manage a difficult airway or an unstable patient on your own, supported by the FACEM in ED and Retrieval specialists.

Typical Day

No such thing as a typical day in this job. You might be heading to Adelaide with an ICU patient – if you do, that’s your whole day, because it’s a 3 hour one way trip. If you aren’t tasked to an inter-hospital transfer, at some point you will likely get an SMS from RFDS operations with a job. You check the email system and read the clinical information – then you call the clinic and speak to the RAN – get the latest details, suggest management or procedures and try to get a feel of how sick the patient is and what equipment you might need to bring. Then it’s a trip into the hospital if you aren’t already there, grabbing your gear and driving or taking a taxi out to the RFDS hanger.

Once there you load up the plane and head off. Most of our retrieval locations are within 1 hour’s flight from Alice Springs, with a few outliers like Elliot and Kiwirrkurra taking 2 hours. Flight time will usually include discussing the plan with your flight nurse and finding out any logistical challenges from your pilot (eg. Day strip only, weights permissible, pilot hours remaining).

Occasionally you may instead be tasked to go to a cattle station, roadhouse or the side of the road but in most cases you will be going to a clinic in a remote community. When you arrive, someone will meet you in a car to take you and your gear to the clinic. The clinics vary in size and equipment but most will have at least a small ‘Emergency’ room.

Typical remote emergency room

It’s hard to really describe accurately the first time you arrive at a remote community clinic. I remember being surprised by all the dogs (and the occasional donkey and camel) and the hurried advice from the flight nurse not to try and pet them. I remember the flies being everywhere (we carry mortein in the plane) and I remember the crowd that greeted us, largely children ages 5-12, mostly with crusty noses and curious smiles and scattered amongst them would be one or two proud elders. I even remember one time where I heard a commotion outside the clinic and popped my head outside to see several children beating a snake with a water bottle, right near where we would be loading the stretcher…

So, at the clinic, you assess your patient(s), perform therapy as necessary and package for transfer. It’s important in this job to not spend unnecessary time on the ground – because you, the plane and the crew are an important resource for a large area of Australia. Once you are ready, you load your patient into the ‘Troopy’.

The Toyota Land Cruiser 70 Troop Carrier, affectionally known as a ‘Troopy’ is the ubiquitous remote area 4wd transport all over the globe. In Central Australia they have been modified to carry one or two stretchers. Having ridden in the back of many of them now, I can definitely say that they are a bumpy ride, but they’re very reliable and spare parts are easy to get.

After arriving at the plane, you load the patient, with or without an escort and head back to Alice Springs – unless another job comes through whilst you are in the air and nearby!

Airstrip intubation due to deterioration – note the fuel barrel table

What is it like to live in Alice Springs

Alice Springs is great. Many of the junior hospital staff are on temporary placements as well – young trainees keen to explore the area. From social nights at the local pubs (Monte’s being the most popular), to bike rides, local hikes and camping trips. The mountain biking and trail running is truly world class with several professional class races held here and the rock climbing hides some real gems and capacity for endless new development.

Within 4 hours driving there are a host of great hiking and camping spots, many with large permanent water holes (some locals have canoes!)– Ormiston Gorge, Palm Valley, Kings Canyon and of course you can’t miss out on a trip to Uluru and you can take a plane there or drive.

Uluru in a rare rainstorm

Local events are varied and the peak season for events and tourists is in Winter. There’s the Finke Desert Race (which I was involved with as a medical officer at Finke), the Beanie Festival, Wide Open Spaces, the typically Territorian Henley on Todd, the Alice Springs Show, Territory Day (the one day of the year you get to buy and use fireworks) and the Camel Races.

Finke Desert Race

Sounds exciting? Well I had a blast. It was a challenging job and I think it begins shaping you as a future consultant. The friends I made and the adventures I had were all great experiences. I urge anyone who might be interested to consider a 6 month rotation up here as a Retrieval Registrar – you’ll get a lot out of it!

This blog was previously published on Life in the Fast Lane and has been republished with permission. If you work in healthcare and have a blog topic you would like to write for doctorportal, please get in touch.

Other doctorportal blogs

Youth detention population in Australia 2015

This bulletin presents information on the youth detention population in Australia, focusing on quarterly trends from June 2011 to June 2015. There were fewer than 900 young people in detention on an average night in the June quarter 2015, just over half (55%) of whom were unsentenced. Numbers and rates of young people in detention dropped slightly over the 4 years, but trends varied among the states and territories. Just over half (54%) of all young people in detention on an average night were Indigenous.

Atlas charts course to improved care

The first detailed national appraisal of variations in health practice has found that Australians are among the world’s heaviest users of antibiotics and antidepressants, and within the country there are major differences in the use of common drugs and treatments for everything from colonoscopies and cataract surgery to antipsychotic medicines for the elderly and hyperactivity drugs for the young.

In what is seen as the first step toward addressing unwarranted variations in the care patients receive, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare has released a report identifying wide discrepancies in the use of everyday medicines and procedures.

Among its findings, the Australian Atlas of Healthcare Variation has revealed that children in some parts of the country, particularly in NSW, are seven times more likely to be prescribed drugs for ADHD than those in other areas, while cataract surgery, hysterectomies, tonsillectomies were three times more common in some areas than others, and patients in some parts were 30 times more likely to undergo a colonoscopy.

AMA President Professor Brian Owler said that, by reflecting how the delivery of health care was organised, the Atlas provided a useful illustration of differences in access to care.

But he highlighted the fact that the Commission itself made no claim about the degree to which differences in care was unwarranted.

“The Atlas is a welcome starting point for further research and examination of health service distribution,” Professor Owler said. “It is not proof that unnecessary or wasteful care is being provided to Australians, and should not be interpreted that way.”

The Commission said that some variation was “desirable and warranted” to the extent that it reflected differences in preferences and the need for care.

It added that “it is not possible at this time to conclude what proportion of this variation is unwarranted, or to comment on the relative performance of health services and clinicians in one area compared with another”.

Senior clinical adviser to the Commission, Professor Anne Duggan, said the average frequency of various services and procedures provided in the Atlas were not necessarily the ideal, and observed that “high or low rates are not necessarily good or bad”.

Nonetheless, she said the weight of local and international evidence suggested much of the differences observed was likely to be unwarranted.

“It may reflect differences in clinicians’ practices, in the organisation of health care, and in people’s access to services,” Professor Duggan said. “It may also reflect poor-quality care that is not in accordance with evidence-based practice.”

Many of the variations identified in the Atlas have been linked to wealth and reduced access to health care in disadvantaged areas.

Professor Duggan said the less well-off tended to have poorer health and so a greater need for care, while some procedures are used more often in wealthier areas.

She said the Atlas showed that rates of cataract surgery were lowest in areas of disadvantage, and increased in better-off locales.

But Professor Owler said the example showed the need to be very careful in drawing conclusions about the reasons for variation.

He said the Atlas showed that the incidence of cataract surgery was highest in the remotest parts of far north Queensland.

“This is because there are no public services available, with private ophthalmologists delivering eye care to Indigenous communities, which is covered by Medicare,” the AMA President said.

He said identifying variation in health care was essential, but this was the first step before determining the causes of variation.

“The Atlas doesn’t tell us what should be the best rates for different interventions and treatments.”

In addition to identifying variations in health care within the country, the Atlas also explored how the care provided in Australia compared internationally.

While acknowledging that differences in the type and quality of data made it difficult to draw direct comparisons, the Atlas nonetheless reported that Australia has “very high” rates of antibiotic use compared with some countries, and Professor Duggan said that, among rich countries, Australia was second only to Iceland in the extant of use of antidepressants.

Professor Owler said that, with the publication of the Atlas, the challenge now was to develop a process to identify variations in practice that were “actually unwarranted, not just assumed to be” and to develop and fund strategies to reduce them by supporting clinically appropriate care, such as by providing clinical services where they are needed.

To view the Atlas, visit: http://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/atlas/

Adrian Rollins

Cut Indigenous imprisonment to help close health gap

Sky-high rates of Indigenous incarceration need to be dramatically reduced if the nation is to close the health gap blighting the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, according to AMA President Professor Brian Owler.

Launching the AMA’s Indigenous Health Report Card 2015, Professor Owler said being imprisoned had devastating lifelong effects on health, significantly contributing to chronic disease and reduced life expectancy.

“Our Report Card recognises that shorter life expectancy and poorer overall health for Indigenous Australians is most definitely linked to prison and incarceration,” the AMA President said.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are hugely over-represented in the nation’s prisons – almost 30 per cent of all sentenced prisoners are Indigenous.

While some progress has been made in recent years in improving infant and maternal health, the AMA President said that imprisonment rates were rising, and the country was set to reach a “grim milestone” next July when, on current trends, the number of Indigenous people in custody will reach 10,000, including 1000 women.

In its Report Card, launched by Rural Health Minister Fiona Nash, the AMA has urged Federal, State and Territory governments to set a national target for cutting rates of Indigenous imprisonment.

The call has come just days after disturbing details of the death of a young Aboriginal woman who was being held in police custody for failing to pay $3622 of fines.

A West Australian coronial inquest has been told the 22-year-old woman, known as Miss Dhu for cultural reasons, was in a violent relationship and using drugs at the time of her arrest last year. While in the South Hedland Police Station she collapsed after complaining of pain and difficulty breathing.

It was later found she had several broken ribs following an attack by her partner, and died from a lethal combination of pneumonia and septicaemia.

Miss Dhu’s death has fuelled calls for WA to overhaul laws regarding the imprisonment of fine defaulters.

But the AMA has said a much broader approach needs to be taken.

Indigenous adults are 13 times more likely to be jailed than other Australians, and among 10 to 17 year-olds the rate jumps to 17 times.

Professor Owler said it was possible to isolate the health issues that led to so many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people landing in prison, and they included mental health conditions, alcohol and drug use, substance abuse disorders and cognitive disabilities.

He said the “imprisonment gap” was symptomatic of the health gap, and the high rates of imprisonment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and the resultant health problems, needed to be treated as a priority issue.

In particular, he said, the health issues identified as being the most significant drivers of Indigenous imprisonment “must be targeted as a part of an integrated effort to reduce Indigenous imprisonment rates”.

Professor Owler said the evidence showed that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people continued to be let down by both the health and justice systems, and firm and effective action was required.

“It is not credible to suggest that Australia, one of the world’s wealthiest nations, cannot solve a health and justice crisis affecting 3 per cent of it citizens,” he said.

Reconciliation Australia Co-Chair Professor Tom Calma said the AMA’s “very substantial” Report Card was latest in a long list of reports identifying the need for action, and urged governments to “get on with it”.

Professor Calma said there had been “some really good outcomes” from recent initiatives to improve prisoner health, particularly moves in many states to ban smoking in jails.

But he said more needed to be done to tackle recidivism, citing figures showing 50 per cent of Indigenous prisoners reoffended.

The Indigenous leader said that this was not surprising because often people getting out of prison returned to the same situation that got them into trouble in the first place, and urged action to tackle the causes of offending in the place, such as alcohol and drug abuse.

Among its recommendations, the AMA has called for funds freed up from reduced rates of Indigenous incarceration to be reinvested in diversion programs; for governments to support the expansion of chronic health and prevention programs by Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations; for such organisations to work in partnership with prison health authorities to improve health and reduce imprisonment rates; and to directly employ Indigenous health workers in prison health services.

Adrian Rollins

Cardiovascular disease, diabetes and chronic kidney disease—Australian facts: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

Cardiovascular disease, diabetes and chronic kidney disease—Australian facts is a series of 5 reports by the National Centre for Monitoring Vascular Diseases at the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare that describe the combined burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD).This report on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people presents up-to-date statistics on risk factors, prevalence, hospitalisation and deaths from these 3 chronic diseases. It examines age and sex characteristics and variations by geographical location and compares these with the non-Indigenous population.

AMA Indigenous Peoples Medical Scholarship 2016

Applications for the AMA Indigenous Peoples Medical Scholarship 2016 are now open.

The Scholarship, open to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people currently studying medicine, is worth $10,000 a year, and is provided for a full course of study.

The Scholarship commences no earlier than the second year of the recipient’s medical degree.

To receive the Scholarship, the recipient must be enrolled at an Australian medical school at the time of application, and have successfully completed the first year of a medical degree (though first-year students can apply before completing the first year).

In awarding the Scholarship, preference will be given to applicants who do not already hold any other substantial scholarship. Applicants must be someone who is of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent, or who identifies as an Australian Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, and is accepted as such by the community in which he or she lives or has lived. Applicants will be asked to provide a letter from an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander community organisation supporting their claim.

The Scholarship will be awarded on the recommendation of an advisory committee appointed by the AMA’s Indigenous Health Taskforce. Selection will be based on:

- academic performance;

- reports from referees familiar with applicant’s work regarding their suitability for a career in medicine; and

- a statement provided by the applicant describing his or her aspirations, purpose in studying medicine, and the uses to which he or she hopes to put his or her medical training.

Each applicant will be asked to provide a curriculum vitae (maximum two pages) including employment history, the contact details of two referees, and a transcript of academic results.

The Scholarship will be awarded for a full course of study, subject to review at the end of each year.

If a Scholarship holder’s performance in any semester is unsatisfactory in the opinion of the head of the medical faculty or institution, further payments under the Scholarship may be withheld or suspended.

The value of the Scholarship in 2016 will be $10,000 per annum, paid in a lump sum.

Please note that it is the responsibility of applicants to seek advice from Centrelink on how the Scholarship payment may affect ABSTUDY or any other government payment.

Applications close 31 January 2016.

The Application Form can be downloaded at: file:///C:/Users/arollins/Downloads/Application-Form-and-Conditions-for-AMA-Indigenous-Peoples’-Medical-Scholarship-2016.pdf

The Indigenous Peoples’ Medical Scholarship Trust Fund was established in 1994 with a contribution from the Australian Government. The Trust is administered by the Australian Medical Association.

The Australian Medical Association would also like to acknowledge the contributions of the Reuben Pelerman Benevolent Foundation and also the late Beryl Jamieson’s wishes for donations towards the Indigenous Peoples’ Medical Scholarship.

Q&A: Dr Murray Haar, 2010 AMA Indigenous Peoples’ Medical Scholarship winner

Dr Murray Haar is a Wiradjuri man who is currently working at Albury Base Hospital. He won the Australian Medical Association Indigenous Peoples’ Medical Scholarship in 2010. In the lead up to the next round of scholarships being awarded, he reflects on how it helped him and what it’s like being an Indigenous doctor in Australia.

What’s your background and how did you decide you wanted to be in medicine.

I grew up in Punchbowl in Sydney’s south west and I had always wanted to study medicine. I was fortunate enough to go to the UNSW Winter School in years 10 and 12 which spurred my interest. I have always been interested in mental health and hope to specialise in psychiatry.

What was your path to medicine?

I went straight from high school into the medical degree at UNSW in 2008. In that time, I had a year away from study where I worked full time at the Kirketon Road Centre, part of what is known as the ‘injecting centre’ in Kings Cross. There my duties involved engaging with clients in health promotion, needle syringe program, groups and sexual health triage.

I completed my degree in 2014 which had six Indigenous doctors in the graduating class, one of the biggest groups in Australian medicine. I am now doing an internship and residency at Albury Base Hospital which is the county of my father’s people, the Wiradjuri nation.

What area of medicine interests you the most?

I want to do psychiatry to enable me to work in addiction medicine. I have been able to complete a term in psychiatry at Albury and most of my relief term was based in Nolan House, an adult inpatient unit. This experience has really enabled me to work in the area where I feel I have the most potential to make a significant difference in patient care.

Patients with a mental illness are amongst the most disadvantaged people in the community. Psychiatry can play such a powerful role to improve the lives of patients, families and communities.

How did the AMA Indigenous Peoples’ Medical Scholarship help you in your studies?

You need real dedication to study medicine, class contact is five days a week, and there’s heaps of study and preparation after hours. Receiving the scholarship from third year onwards helped me give my studies everything I’ve got, particularly in the last year.

I also got some great help from the UNSW’s Indigenous Unit, Nura Gili which specifically helps Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students with academic support and assistance navigating the university world.

What advice would you give other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students who are thinking of studying medicine?

Don’t listen to anyone who discourages you. There is plenty of support for you, from the university, from scholarships and from other Indigenous doctors. There is improvement in the state of Indigenous health, but the gap is still wide. It’s really important that we play our part in closing it.

What has your experience been of being an Indigenous doctor so far? Are there any unique challenges or advantages?

I am incredibly privileged to be an Aboriginal doctor, particularly when looking after an Aboriginal patient with whom I can empathise and form an instant connection and understanding through our unique appreciation of family and connectedness. The challenges can be tough at time as the workplace is like any other and not free of racism or bullying.

How do you think your perspective or your path to medicine has differed as an Indigenous man?

I feel as an Aboriginal doctor you bring a unique perspective to the practice of medicine. With a set of values and respect for family, land and spirituality and an understanding of the health disparity of our peoples compared to the rest of Australians. There is still much work to be done to close the gap, but more Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander doctors will go a long way to help this.

The next round of AMA Indigenous Peoples’ Medical Scholarship opens on November 1. If you work in healthcare and have a blog topic you would like to write for doctorportal, please get in touch.

Other doctorportal blogs

Time to launch NATSIHP

New Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull has made it clear he wants to reshape the focus and direction of the Coalition Government. He talks of a modern Government with modern approaches. Let’s hope this enthusiasm translates to Indigenous health.

While former PM Tony Abbott made a virtue of his commitment to Indigenous issues – including his pledge to spend a week each year living and working in an Indigenous community – genuine new policy rollout was slow under his leadership.

A prime example of this is the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan (NATSIHP).

In July 2013, the former Labor Government launched a new NATSIHP, which set out a 10-year framework for the direction of Government policy to improve the appalling health status of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The plan had bipartisan support.

The development of the NATSIHP was a clear example of the Government working in partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to achieve improved health outcomes for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community.

But, in the two years since the launch of the NATSIHP, we are yet to see the new Government put its commitment into action.

The Government has developed an Implementation Plan for the NATSIHP, but has not yet launched it.

The Implementation Plan provides the basic architecture for turning the NATSIHP into concrete action. More work on defining service models, workforce requirements, and funding strategies is needed.

Guided by the Implementation Plan, the NATSIHP is capable of driving real progress towards the best possible health outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and could realise health gains in a relatively short period of time.

To achieve these improvements, a key strategy is for the Government to identify areas of poor health and inadequate services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and direct investment accordingly.

This must include increased support for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community controlled health services to enable them to fulfil their pivotal role in improving health outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

The NATSIHP recognises that culture is central to the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and this must be reflected in practical ways throughout the actions of the NATSIHP Implementation Plan.

The NATSIHP broke new ground with the identification of racism as a key driver of ill-health. The implementation of the NATSIHP must provide a clear focus on strategies to address racism, and strengthen the cultural safety of Australia’s healthcare system.

This includes identifying and eradicating systemic racism within the health system and improving access to, and outcomes across, primary, secondary, and tertiary health care.

While we need to continue to strengthen health care, we also need to enhance our focus on building pathways into the health profession for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, as well as supporting the existing Indigenous health workforce.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are significantly underrepresented across all health professions, particularly medicine, nursing and allied health. This must change.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health professionals are an important resource to improve Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health, as they are able to use their unique cultural and clinical expertise to contribute to greater health outcomes for Indigenous people.

Specific actions to address Indigenous health workforce shortages must be reflected in the actions of the NATSIHP Implementation Plan.

NATSIHP implementation is long overdue. It must occur without further delay.

The initial Implementation Plan was to be developed within 12 months of the NATSIHP’s release. That time is long gone.

At a Senate Estimates hearing in June, Government officials indicated that the Implementation Plan for the NATSIHP was still being developed, and that it would be released soon. That was three months ago, and still no action.

PM Turnbull strengthened and reordered his Health portfolio team upon taking over the leadership, with now Rural Health Minister Senator Fiona Nash retaining responsibility for Indigenous health. I will be discussing the inactivity on NATSIHP with her at the earliest opportunity.

The AMA’s Indigenous Health Taskforce is keen to see the Government make NATSIHP a reality – and a success story.

more_vert

more_vert