We report the first case of acute parkinsonism following disseminated melioidosis with multiorgan abscesses in a 62-year-old man. After 1 month of treatment with levodopa, the parkinsonism resolved completely. Melioidosis should be considered as a possible cause for parkinsonism in endemic areas.

A 62-year-old man presented to our tertiary hospital’s emergency department with a 4-week history of fever associated with lethargy and constitutional symptoms. For 9 days before admission, he had been vomiting two to three times per day. He had longstanding diabetes and hypertension and worked for the local city council as a truck driver, transporting water to local gardens and public areas. About 2 months previously, he had sustained an abrasion on his left foot that had healed completely at time of presentation.

On initial assessment, he had a blood pressure of 129/78 mmHg, a heart rate of 111 beats/min, an SpO2 of 96% in room air, and a respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min. He was clinically dehydrated and his body temperature was 38.8°C. His abdomen was soft and non-tender, with hepatomegaly of two fingers’ breadth. Respiratory examination revealed left basal lung crepitations. Results of the clinical assessment, including cardiovascular and neurological examinations, were otherwise normal.

The patient’s initial blood investigations revealed an elevated random blood glucose level (11.6 mmol/L; reference interval [RI], 4.4–6.1 mmol/L) and white cell count (12.1 × 109/L; RI, 4.0–11.0 × 109/L) with neutrophilia (93%). His haemoglobin level was low (117 g/L; RI, 130–170 g/L). His sodium concentration was low (115 mmol/L; RI, 135–145 mmol/L) and his potassium concentration was normal (3.5 mmol/L; RI, 3.5–5.0 mmol/L). His creatinine level was low (45 µmol/L; RI, 70–104 µmol/L) and C-reactive protein level was elevated (116.2 mg/L; RI, 0–100 mg/L). Platelet count (240 × 109/L; RI, 150–400 × 109/L) and urea levels (2.9 mmol/L; RI, 2.5–6.7 mmol/L) were normal. Urine analysis, including culture and sensitivity tests, yielded normal results. Leptospirosis IgG and IgM test results were negative. Results of serological testing for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, syphilis and HIV were negative. However, blood culture tested positive for Burkholderia pseudomallei.

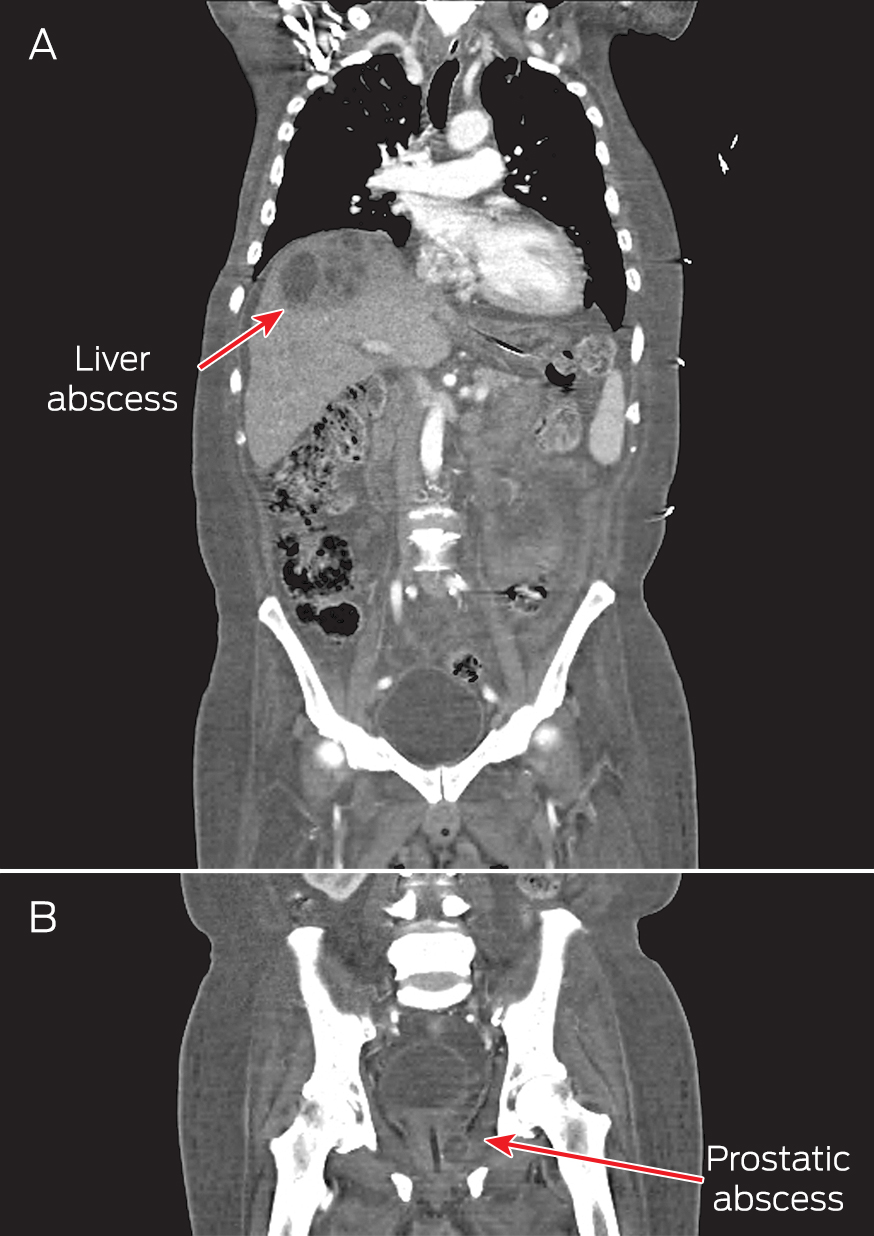

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the thorax, abdomen and pelvis showed right pleural effusion and liver and prostate abscesses (Box). The patient was diagnosed with disseminated melioidosis with multiorgan abscesses, and he was started on intravenous imipenem for a planned duration of 6 weeks. Supportive therapy with intravenous normal saline was instituted to resolve his dehydration. Therapeutic drainage of the liver abscess and right pleural effusion was performed under ultrasound guidance.

The patient’s condition responded well to treatment, showing clinical improvement after 3 days. He became afebrile, and his blood parameters normalised with a gradual increase in his serum sodium level to 122 mmol/L over 3 days.

However, on Day 7 of admission, he started feeling weak, requiring help to ambulate. He was noted to be slow in his movements and in answering questions, with slurred speech. He complained that his upper limbs and trunk felt stiff. There were multiple new skin abscesses on his forehead. On neurological examination, he was alert, with negative Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs. Results of cranial nerve examination were normal. There was generalised rigidity of the neck, trunk and limbs. He had mask-like facies, bradykinesia and bradyphrenia, with monotonous speech and fine resting tremor of both hands. Medical Research Council muscle power grading of all four limbs was 4/5 with normal reflexes. Sensations were otherwise normal, and he had no cerebellar signs. He had not been given any antidopaminergic medications.

A CT scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was normal. A lumbar puncture revealed clear cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) with a cell count of 20 cells/mm3, predominantly neutrophils (RI, < 5 cells/mm3, predominantly lymphocytes). His total CSF protein level was 405 mg/L (RI, 150–450 mg/L), and CSF glucose level was 3.1 mmol/L (RI, 2.8–4.2 mmol/L) with a CSF to blood glucose ratio of > 0.5 (RI, > 0.5). CSF Ziehl–Neelsen smear and polymerase chain reaction results were negative for tuberculosis. The CSF culture was negative for B. pseudomallei.

A diagnosis of parkinsonism secondary to melioidosis was made after excluding other causes of parkinsonism, including drug-induced parkinsonism and extrapontine myelinolysis. Extrapontine myelinolysis was unlikely in our patient as the correction of hyponatraemia was gradual, and there were no supportive MRI changes.

The patient was treated symptomatically with levodopa/benserazide 50/12.5 mg twice daily for a month. The intravenous antibiotic for melioidosis was continued. After 1 month, his parkinsonism symptoms resolved and his antiparkinson medication was stopped. An ultrasound of his abdomen showed resolution of the abscess. Repeated blood culture showed no growth. He was subsequently discharged after a 1.5-month stay, and prescribed oral co-trimoxazole (trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole 320/1600 mg) 12-hourly and oral doxycycline (100 mg 12-hourly) for 3 months.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of parkinsonism secondary to melioidosis. Melioidosis is an infection caused by B. pseudomallei, a gram-negative bacterium transmitted through direct skin contact with contaminated soil. It is endemic in the Asia–Pacific region, with a reported incidence of 4.4 per 100 000 person-years in north-eastern Thailand and 50.2 per 100 000 person-years in the Top End of the Northern Territory.1,2

Neurological complications of melioidosis are rare. In the Darwin Prospective Melioidosis Study, only 14 of 540 patients (3%) developed neurological complications following melioidosis over a 20-year study period.2,3 The clinical features reported include unilateral limb weakness, cerebellar signs, brainstem signs and flaccid paraparesis.2,4 Parkinsonism and extrapyramidal signs have not been reported in previous case series.

Various infective organisms have been reported to cause post-infectious parkinsonism, including dengue virus,5 Japanese encephalitis B virus,6 West Nile virus,7 encephalitis lethargica8 and Streptococcus species.9 It is postulated that infective organisms can cause parkinsonism by three different mechanisms.

The most widely accepted mechanism is via direct infiltration of the causative organism into the central nervous system. Patients usually have pathological changes on imaging of the central nervous system and abnormal CSF findings. In the Darwin Melioidosis Prospective Study, of the 14 patients who developed neurological complications, 10 had meningoencephalitis, two had myelitis and two had cerebral abscesses.2 All were noted on MRI to have abnormal T2-weighted hyperintensities and had abnormal results of CSF analysis, with mononuclear pleocytosis and elevated protein levels.2

The second mechanism involves endotoxin lipopolysaccharide released from the gram-negative bacterial cell wall causing damage to the blood–brain barrier. There is subsequent microglia and macrophage activation, as well as the release of cytokines and oxygen radicals. This results in dopaminergic neurone damage. This pathophysiological mechanism has been postulated as a possible model for development of Parkinson disease based on animal studies.10

The final possible mechanism involves the development of antibasal ganglia antibodies with resultant insult to the basal ganglia. Antibasal ganglia antibodies are commonly implicated in many movement disorders, including chorea and tics.11 Acute parkinsonism with antibasal ganglia antibodies following streptococcal infection has been reported.9

Our patient did not have MRI changes to suggest a pathophysiological mechanism of direct invasion of the infective organism into the central nervous system. Although the CSF culture was negative and the protein level was normal, there was pleocytosis with predominant neutrophils, suggesting an ongoing inflammatory process in the central nervous system.

The onset of parkinsonism was delayed and developed when the patient was recovering from the bacteraemia, as evidenced by improving blood indices and vital signs. This suggests, at least in our patient, that the most probable mechanism for the parkinsonism was an immune-mediated process, either by liposaccharide endotoxins or antibasal ganglia antibodies. Unfortunately, we do not have a facility to test for antibasal ganglia antibodies at our centre.

The recommended treatment for neurological melioidosis includes parenteral ceftazidime or a carbapenem for 6 to 8 weeks, followed by maintenance treatment with oral doxycycline or co-trimoxazole.12 However, to date, there is no standard guideline for managing post-infectious parkinsonism. Previous cases of post-infectious parkinsonism were treated symptomatically with levodopa and other anti-parkinson agents.13 Evidence for immunotherapy for post-infectious parkinsonism is anecdotal at best.5,13

In conclusion, parkinsonism could be a neurological complication of melioidosis. Despite its rarity, melioidosis should be considered as a differential diagnosis of parkinsonism, particularly in endemic areas. In our case, the pathophysiological mechanism appears to be secondary to immunological response rather than direct CNS infiltration. Little is known about the treatment of post-infectious parkinsonism. However, at least in our patient, it was self-limiting and responded well to symptomatic treatment.

Abscesses due to melioidosis in a 62-year-old man

more_vert

more_vert