Clinical records

Case 1

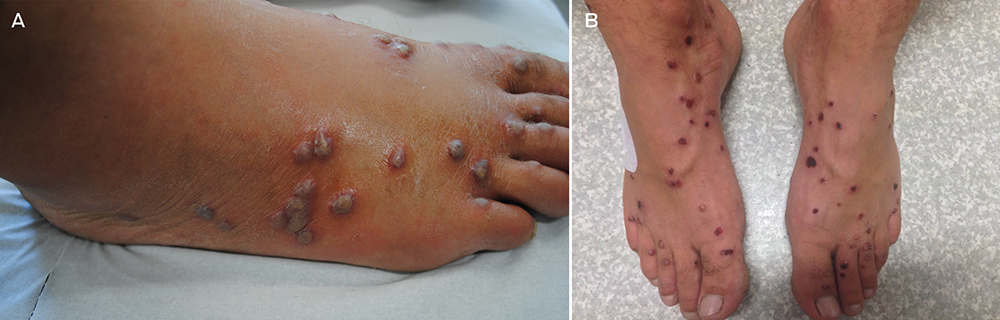

A 55-year-old man with no medical history or allergies presented in May 2015 with a widespread, pruritic, whiplash-like rash (Figure 1). On examination, multiple erythematous papules in a linear distribution, corresponding to areas of excoriation, were noted on his trunk, limbs, forehead and scalp. The rash had developed 12 hours after a meal containing fresh shiitake mushrooms. There were no associated systemic symptoms and the patient’s condition did not improve with topical administration of betamethasone dipropionate 0.05%. Based on dietary history and the characteristic appearance of the rash, a diagnosis of shiitake dermatitis was made. The rash resolved in 3 weeks without further treatment. The patient experienced a recurrence 5 months later, after eating another meal containing shiitake mushrooms.

Case 2

A 30-year-old man with no comorbidities or allergies presented in March 2015 with a 2-day history of a striking, linear, erythematous eruption (Figure 2). He was systemically well, but reported associated perioral tingling and pharyngitis, which were unresponsive to 10 mg oral cetirizine. Examination revealed linear groupings of papules on an erythematous urticated base on his forehead and trunk. Despite denying pruritus or excoriations, relative sparing of the central back (out of the patient’s reach) was noted. Further questioning revealed ingestion of lightly cooked shiitake mushrooms the night before the onset of symptoms. No relatives who had eaten the same meal were affected. The patient was diagnosed with shiitake dermatitis, and the rash resolved completely without treatment.

Case 3

A 44-year-old man presented in August 2015 with a 2-day history of a flagellate erythematous rash (Figure 3). His past history included ischaemic heart disease, hypercholesterolaemia and rosacea. He had eaten raw shiitake mushrooms while cooking, and woke the next morning with a rash on his arms. Despite treatment with 25 mg oral prednisolone and topical betamethasone valerate 0.02%, prescribed by his general practitioner, the rash rapidly extended to his trunk, shins and scalp. His full blood count, C-reactive protein level and biochemistry results were unremarkable. A diagnosis of shiitake dermatitis was made. The patient’s wife, with whom he had shared the cooked meal, was asymptomatic, and the patient had previously eaten cooked shiitake without problems. Ten days later, the rash was resolving rapidly, with mild hyperpigmentation.

Shiitake mushrooms (Lentinus edodes) account for 20% of mushroom production worldwide1,2 and are the second most commonly eaten mushroom variety.1,3 Originally, most shiitake were log-grown in Japan. Since the late 1980s, most shiitake have been cultivated on a sawdust-based substrate in China.4,5 Shiitake are used in Asian medicine for their antihypertensive, anticarcinogenic and cholesterol-reducing qualities.1,5 Shiitake spores can cause IgE-mediated illness, such as hypersensitivity pneumonitis, asthma and allergic rhinitis.1,3,6 Shiitake can also cause contact urticaria, protein contact dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis.1,3,6 In this article, we present the first three published cases of shiitake dermatitis in Australia. Systemic dermatitis caused by ingested allergens has also been reported with other foods, including spices, garlic, onions and root vegetables, metals, drugs, and preservatives.7,8

Shiitake dermatitis is also known as flagellate erythema, flagellate dermatitis and toxicodermia.3 It was first described in Japan in 1977, in Europe in 2006 and in the United States in 2010.1,2 Flagellate erythema occurs with all forms of shiitake — fresh, dried, powdered, boiled, baked, grilled and fried.2,5 It has been reported from adolescence to old age, and is more common in men.2

The highly distinctive rash develops following the ingestion of undercooked shiitake mushrooms by susceptible individuals. Onset usually occurs 12–48 hours after intake, although the reported range is 2 hours to 5 days.1 Intensely pruritic, linear, erythematous papules and petechiae develop on the trunk, limbs, head and neck,2 sparing the oral mucosa. The flagellate morphology is attributed to the Koebner phenomenon.2,3 There may be associated local oedema, fever, malaise, lip tingling, dysphagia and diarrhoea.1,9,10 Up to 47% of patients display ultraviolet A photosensitivity and photo-aggravation.3,9 Differential diagnoses include the flagellate rash associated with bleomycin, dermatomyositis, adult-onset Still disease, and HIV with hypereosinophilic syndrome.11

Lentinan, a thermolabile polysaccharide component of shiitake mushrooms, is the cause of shiitake dermatitis.1–3,5,9 Lentinan undergoes a conformational change at 130–145°C, so it is recommended that shiitake are cooked at temperatures of 150°C or greater to prevent toxicity.10 The pathogenesis remains unclear, but frequent case reports of single patients who had take part in shared meals and the delayed time course support the likelihood of an allergic reaction,2,10 with a possible role for exacerbating cofactors, such as use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or diuretics, and exposure to ultraviolet A light.1,9 A trial of 519 patients in Japan who received intravenous lentinan chemotherapy yielded nine cases of flagellate erythema; extrapolating from these data, up to 2% of the population will be vulnerable to shiitake dermatitis.1,2

A case of shiitake dermatitis following ingestion of log-grown shiitake was recently reported in a patient who had previously tolerated substrate-grown shiitake from China.5 The authors of this report proposed that shiitake dermatitis may occur only with log-grown mushrooms. This hypothesis is supported by the low incidence of shiitake dermatitis in China, where the shiitake are substrate-grown, and the lower rates in Japan since 1992, when local production switched to substrate-grown mushrooms and the Japanese government began importing substrate-grown shiitake from China.4,5 Most cases in Japan were reported before 1998,9 typically during the harvest season for log-grown shiitake mushrooms.2 In Australia, shiitake are produced by both cultivation methods, and some shiitake are imported from China.12

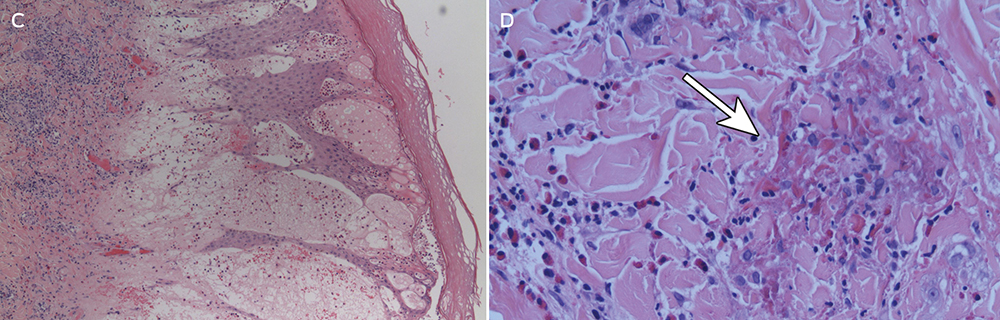

The diagnosis is made clinically, and may be confirmed by oral re-challenge. Histopathological testing of skin biopsy specimens does not provide specific diagnostic information; it generally reveals elongation of rete ridges, spongiosis, degenerating keratinocytes, dermal oedema, and a superficial and perivascular lymphocytic infiltration with eosinophils and neutrophils.1,2 Prick and patch tests conducted by authors of previously published case reports have yielded conflicting results.1,2,10 Positive patch test results have also been obtained in control subjects, further limiting their usefulness in flagellate erythema.2,10

No treatments have been shown to be effective for shiitake dermatitis, although oral antihistamines and topical and oral corticosteroids are often prescribed. Given the high reported rate of ultraviolet A photosensitivity, patients should be given guidance on careful photoprotection.1 The prognosis is excellent, with improvement from 2 days and resolution by 3 weeks.1,2

In Australia, only four confirmed cases and one possible case of shiitake dermatitis were reported in 11 years (Appendix); these were reported to the NSW Poisons Information Centre between January 2004 and April 2015. No cases have been reported to the poisons information centres in Western Australia, Victoria and Queensland. Given our experience of three cases at a tertiary hospital within 12 months, and the prevalence of shiitake consumption in Australia, we believe that shiitake dermatitis is under-recognised. The mushroom industry heavily endorses the health benefits of shiitake as a low kilojoule source of dietary fibre, protein, vitamins, antioxidants and minerals. Considering the availability of shiitake-based health supplements on the internet,1 the popularity of Asian cuisine, and the production of log-grown shiitake in Australia today,12 we anticipate an increasing incidence of shiitake dermatitis. Documenting the preparation temperature, cultivation method and source of the shiitake mushrooms in future cases may help elucidate the pathogenesis.

Lessons from practice

-

Shiitake dermatitis is probably under-recognised and under-reported in Australia

-

The diagnosis is made clinically, based on dietary history and a characteristic erythematous flagellate rash

-

The prognosis is excellent, but patients should be advised to avoid shiitake or to ensure it has been cooked at temperatures of 150°C or greater to prevent further episodes

-

Primary care practitioners, such as general practitioners and emergency physicians, should be aware of the diagnosis to avoid unnecessary investigations and treatments

more_vert

more_vert