The distinction between type 1 and type 2 diabetes was described as early as 500–600 BC by Indian physicians Sushruta and Charaka—type 1 being associated with onset in youth, and type 2 linked to obesity. Today, diabetes is recognised as a complex and heterogeneous disease that can affect people at different life stages. As such, the classic phenotypes of age of onset and metabolic features that once helped to define the types of diabetes are now far less useful clinical indicators. Modern appreciation of the heterogeneity of diabetes is not simply a product of a deeper understanding of the genetics, risk factors, and pathophysiology of the disease.

Preference: Genetics

342

[Correspondence] Health economics

Joseph L Dieleman and colleagues (June 18, p 2521)1 should be congratulated for their study on health spending prediction. However, this is a multifactorial and complex problem. The ongoing global financial crisis, rapid development of novel technologies that can increase or reduce total health expenditures, the emergence of often unexpected diseases such as the Zika virus, changing population genetics and epigenetics, and environmental changes and disasters are key parameters that impede the accuracy of spending prediction models.

News briefs

Reprogramming brain cells may help Parkinson’s

Cells similar to dopamine neurons can be induced by treating non-neuronal brain cells with a specific combination of DNA transcription factors, according to a study published in Nature Biotechnology. The new reprogramming method has been demonstrated both in cultured human cells and in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. A defining feature of Parkinson’s disease is the progressive death of a specific group of neurons that secrete dopamine. Although several treatments are available to patients, including the chemical precursor of dopamine, none change the course of the disease. A decades-long research effort has sought to develop a disease-modifying therapy in which dopamine neurons or their precursors would be generated in the laboratory and transplanted into the brain. The authors of this study described a different approach to cell replacement that does not require cell transplantation. By testing a number of genes known to be important for dopamine neuron identity, they identified three transcription factors and a microRNA that reprogrammed human brain cells called astrocytes as cells that resemble dopamine neurons. The authors used a toxin to kill dopamine neurons in mice and then delivered the genes for the four factors to the brain using a system designed to express the genes only in astrocytes. Some astrocytes were successfully reprogrammed, acquiring characteristics of dopamine neurons, correcting several behavioral symptoms caused by dopamine neuron loss. Substantial further research would be needed before this approach could be considered for human trials, the authors noted.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3835

Protein that causes liver disease found

Australian scientists have published research in Nature Genetics which identifies that variations in the interferon lambda 3 (IFNL3) protein are responsible for tissue damage in the liver, paving the way for new treatments to be developed. The international team, led by Professor Jacob George and Dr Mohammed Eslam at the Westmead Institute, had previously identified that the common genetic variations associated with liver fibrosis were located on chromosome 19 between the IFNL3 and IFNL4 genes. The team analysed liver samples from 2000 patients with hepatitis C, using state-of-the art genetic and functional analysis, to determine the specific IFNL protein responsible for liver fibrosis. The team demonstrated that there was increased migration of inflammatory cells from blood to the liver following injury, increasing IFNL3 secretion and liver damage. Notably, this response was determined to a great extent by an individual’s genetic makeup. “We have designed a diagnostic tool based on our discoveries, which is freely available for all doctors to use, to aid in predicting liver fibrosis risk,” Prof Jacob said. “This test will help to determine whether an individual is at high risk of developing liver fibrosis, or whether a patient’s liver disease will progress rapidly or slowly, based on their genetic makeup.” The research team will now extend their work to further understand the fundamental mechanisms of how IFNL3 contributes to liver disease progression and to translate these discoveries into new therapeutic treatments.

News briefs

Hidden risk population for thunderstorm asthma

Research presented at the Thoracic Society for Australia and New Zealand (TSANZ) Annual Scientific Meeting in Canberra last month identified “a potentially hidden and significant population susceptible to thunderstorm asthma”. “This is a wake-up call for all of Australia, but particularly Victoria as it prepares for its next pollen season,” said Professor Peter Gibson, president of TSANZ. “Many more people than previously thought are at risk of sudden, unforeseen asthma attack. It is essential that we invest more research into this phenomenon and educate our health services and public to take preventative and preparedness measures.” Nine people died in Victoria late last year and over 8500 required emergency hospital care when a freak weather event combining high pollen count with hot winds and sudden downpour led to the release of thousands of tiny allergen particles triggering sudden and severe asthma attacks. Those most seriously affected were people who were unaware they were at risk of asthma and therefore had no medication to hand. In the study of over 500 health care workers, led by the Department of Respiratory and Sleep Medicine, Eastern Health, Victoria, almost half the respondents with asthma experienced symptoms during the thunderstorm event. Most took their own treatment, a few sought medical attention and one was hospitalised. More alarming was the 37% of respondents with no prior history of asthma who reported symptoms such as hayfever, shortness of breath, cough, chest tightness and wheeze during the storms. The study also found that people with a history of sensitivity to environmental aeroallergens (eg, ryegrass or mould) were far more likely to report symptoms than those with a history of either no allergy or allergy to dust mite/cats. Physical location, described as predominantly indoors versus outdoors, was not a risk factor. “This study gives us an indication of the proportion of our population that might be at risk of thunderstorm asthma, but are unaware of it as they have no history of asthma. It also suggests that a history of hayfever is one of the greatest risk factors,” said lead researcher Dr Daniel Clayton-Chubb. “The key message from our work is that anyone with hayfever should ensure that they have ready access to quick-acting asthma treatments such as bronchodilators at all times, but particularly in pollen season or if thunderstorms are predicted. Severe thunderstorm asthma symptoms can strike rapidly and without warning.”

New genetic causes of ovarian cancer identified

A major international collaboration has identified new genetic drivers of ovarian cancer, findings which have been published in Nature Genetics. The study involved 418 researchers from both the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium, led by Dr Andrew Berchuck from the United States, and the Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2, led by Professor Georgia Chenevix-Trench from QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute. Professor Chenevix-Trench said it was known that a woman’s genetic make-up accounts for about one-third of her overall risk of developing ovarian cancer. “This is the inherited component of the disease risk,” Professor Chenevix-Trench said. “Inherited faults in genes such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 account for about 40% of that genetic risk. Other variants that are more common in the population (carried by more than one in 100 people) are believed to account for most of the rest of the inherited component of risk. We’re less certain of environmental factors that increase the risk, but we do know that several factors reduce the risk of ovarian cancer, including taking the oral contraceptive pill, having your tubes tied and having children. In this study, we trawled through the DNA of nearly 100 000 people, including patients with the most common types of ovarian cancer and healthy controls. We have identified 12 new genetic variants that increase a woman’s risk of developing the cancer. We have also confirmed that 18 variants that had been previously identified do increase the risk. As a result of this study, we now know about a total of 30 genetic variants in addition to BRCA1 and BRCA2 that increase a woman’s risk of developing ovarian cancer. Together, these 30 variants account for another 6.5% of the genetic component of ovarian cancer risk.”

News briefs

Gene linked to “Rain man” brain disorder

Murdoch Childrens Research Institute (MCRI) researchers have discovered a new gene linked to a congenital brain abnormality experienced by the person who inspired the movie Rain Man. Associate Professors Paul Lockhart and Rick Leventer led an international team which has discovered the first gene, called Deleted in Colorectal Cancer (DCC), known to cause the loss of the main connection between the two halves of the brain, in the absence of any other syndromes linked to the condition. About one in 4000 babies are born with agenesis of the corpus callosum (ACC). Symptoms of ACC, where the corpus callosum is missing, are varied but can include intellectual disability, autism and cerebral palsy. Individuals with ACC who also have the DCC gene change often struggle with “mirror movements”. This means if they move one hand, the other hand automatically moves in the same way. This causes problems with everyday tasks including eating, washing the dishes, writing, driving a car and using a mobile phone or tablet. Lockhart and Leventer’s study suggests that individuals with ACC caused by mutations in this gene have much better neurodevelopmental outcomes than people with ACC linked to a particular syndrome. This holds important implications for decision making if the condition is detected during prenatal testing, they wrote. “The results of this research will provide better information to parents regarding potential outcomes for their children, helping to make more informed reproductive decisions,” Lockhart said. “Our research also provides important new information about how nerves connect to the appropriate part of the brain during development of the embryo. This has potential implications for our understanding of a broad range of neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism spectrum disorder. This gene is playing a role in how nerves connect with each other and transfer information. Deficits or problems in this process are emerging as associated with autism spectrum disorder.” The finding was published in Nature Genetics.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ng.3794

Life expectancy booming

By 2030 there is a greater than 95% probability that life expectancy at birth among Australian men will surpass 80 years, and a greater than 27% probability that it will surpass 85 years, according to research published in The Lancet. Researchers from Imperial College London and other international sites, developed 21 forecasting models, then applied the approach to project age-specific mortality to 2030 in 35 industrialised countries with high quality vital statistics data. They used age-specific death rates to calculate life expectancy at birth and at age 65 years, and probability of dying before age 70 years. The increase in life expectancy will be largest in South Korea, some western European countries and some emerging economies. South Korean women are predicted to live beyond 86 years by 2030, with a 57% probability that their life expectancy will be beyond 90 years. The smallest increases will be in the USA, Japan, Sweden, Greece, Macedonia, and Serbia. “Countries with high projected life expectancy are benefiting from one or more major public health and health-care successes. Examples include high-quality healthcare that improves prevention and prognosis of cardiovascular diseases and cancers, very low infant mortality, low rates of road traffic injuries and smoking (Australia, Canada, and New Zealand), and low body-mass index (French and Swiss women) and blood pressure (Canada and Australia).”

Outstanding doctor from outstanding Israeli hospital visits Down Under

Internationally renowned Israeli doctor Nitza Heiman Newman is currently visiting Australia representing the Soroka Medical Centre, the only major medical centre in the entire Negev.

It is one of the largest and most advanced hospitals in Israel, serving a population of more than one million people, including 400,000 children, in a region that accounts for more than 60 per cent of the country’s total land a

Soroka also serves as a teaching hospital of the Ben-Gurion University Medical School.

But what makes Soroka even more unique in the region is that in a nation often embroiled in conflict, it caters for everyone.

“We treat people by the severity of the medical problems they have, not by any religion or culture,” Dr Newman said.

“You can see in our wards, in the same room, Israelis, Jews, Arabs, Bedouin and more.

“And you can see the changes of the people in those wards. It can sometimes start out with – I wouldn’t say with tension, but maybe with some suspicion amongst the patients and those who visit them. But within 24 hours they are getting along better and visitors are often bringing along cakes for everyone in the room.”

Another thing making Soroka a standout facility is the way it is prepared for trauma. In a war zone, this is a necessity.

“What we see a lot of unfortunately is military trauma in our area. The last time there was a serious breakout two years ago our helipad was very, very busy and we were treating a constant flow of injured soldiers and civilians,” Dr Newman said.

“We are one of the biggest medical centres in Israel and definitely as a trauma centre. But we are also a general hospital with more than a thousand beds.

“We do everything, including transplants. Our specialty is genetics and we also have the biggest delivery room in the country – delivering 55 new babies every day.”

Dr Newman says Soroka is an example to the world, which is part of her reason for being in Australia.

She is speaking at forums about the medical centre and also about the United Israel Appeal program called Professions for Life, which assists new immigrants to Israel to re-certify in their chosen professions.

“If you make the transition easier for new immigrants you make their lives easier and they integrate faster,” she said.

“It makes life more enjoyable for them and for those who absorb them into the community.”

Born in Israel, the only child of Holocaust survivors, Dr Newman served in a range of positions in the Israel Defense Forces, including as an officer in the Golani Brigade. Her last army position was as a company commander in a female officers’ course.

She took a year off from medicine to direct a school in Be’er Sheva for gifted children, before taking a residency in pediatric surgery at Soroka Medical Center in Be’er Sheva.

She then did a year-long fellowship at Great Ormond Street Hospital in London in the field of pediatric oncology surgery, a field that she developed at the hospital.

Since 2005, Dr Newman has been responsible for the Dr. Gabi and Eng. Max Lichtenberg scientific program in surgery for outstanding staff at Ben-Gurion University.

From 2009-2013, she was a member of the Be’er Sheva city council and responsible for the health and environment portfolio.

Since 2010 she has been the deputy hospital director, in charge of medical personnel, children’s division, maternity division, gynecology, psychiatry and now rehabilitation as well.

Chris Johnson

News briefs

Genes found linked to autism and intellectual disability

Researchers from the University of Adelaide have helped identify 91 genes, 38 of which are completely new, linked to autism and intellectual disabilities. Most of the gene mutations (65%) were inherited, suggesting not all of them were sufficient on their own to cause disease. The researchers had hoped data from 11 730 cases would allow them to distinguish between genes linked to autism and those linked to intellectual disability, but found that most of the 91 genes were affected in both conditions. Only eight gene mutations linked to autism were not present in the group with intellectual disabilities, while 17 mutations linked to intellectual disabilities were absent in the group with autism. The researchers also found that the pattern of mutations in high functioning autism differs from the pattern seen in autism with intellectual disability — an important finding for diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic reasons, said the authors. The study, published in Nature Genetics, commenced in 2009 and was conducted with the support of an international consortium, the Autism Spectrum/Intellectual Disability network. The network involves 15 centres across seven countries and four continents; 11 730 autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disability and developmental disability cases were tested and, from these, 2383 cases with intellectual disability came from Adelaide.

Dormant breast stem cells linked to pregnancy growth

Researchers from Walter and Eliza Hall Institute have used advanced imaging technology to find a long-lived type of breast stem cell that is responsible for the growth of the mammary glands during pregnancy, enabling lactation. The newly discovered stem cells, which respond to progesterone and oestrogen, may also be linked to a high risk form of breast cancer. The discovery was made by Dr Nai Yang Fu, Dr Anne Rios, Professor Jane Visvader and Professor Geoff Lindeman as part of a 20-year research program into how the breast develops from stem cells and how breast cancers can arise from stem cells and developing breast tissue. The research has been published in Nature Cell Biology. The research also revealed that the stem cells with high levels of two proteins called tetraspanin8 and Lgr5 have many similarities to a subtype of “triple negative” breast cancers known as claudin-low cancers. “Compared to other types of breast cancer, claudin-low cancers have a high chance of recurrence after treatment, leading to a poor prognosis for patients,” Professor Visvader said.

News briefs

NSAIDs don’t stop back pain

A systematic review from the George Institute for Global Health has found that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) commonly used to treat back pain provide little benefit, but cause side effects. Published in the Annals of Rheumatic Disease, the review, which examined 35 trials involving more than 6000 people, found that only one in six patients treated with NSAIDs achieved any significant reduction in pain. Patients taking NSAIDs were 2.5 times more likely to suffer from gastro-intestinal problems such as stomach ulcers and bleeding. Most clinical guidelines currently recommend NSAIDs as the second line analgesics after paracetamol, with opioids coming at third choice. Lead author Associate Professor Manuela Ferreira said the review highlighted an urgent need to develop new therapies to treat back pain. “When you factor in the side effects which are very common, it becomes clear that these drugs are not the answer to providing pain relief to the many millions of Australians who suffer from this debilitating condition every year.”

Gene discovery could prevent onset of MD

An international group including researchers from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research has found that mutations in a gene called SMCHD1 can cause a rare syndrome called bosma arhinia microphthalmia syndrome (BAMS), in which the nose fails to form during embryonic development. The same gene is also faulty in people with an inherited form of muscular dystrophy called facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy type 2 (FSHD2). Published in Nature Genetics, the research compared the genetic changes in SMCHD1 causing BAMS and FSHD. They found that FSHD2 was caused when the protein SMCHD1 was damaged and can no longer function normally. They also found that in children with BAMS the opposite happened – the nose fails to develop in instances where SMCHD1 is activated. “This is really exciting because it gives us clues about how to design medicines that boost SMCHD1’s activity to protect the body from the development of FSHD2,” one of the authors said.

Gene tests on ‘don’t do’ list

Medical experts have taken aim at ‘direct to consumer’ genetic testing services amid concerns that they are causing unnecessary expense and alarm.

Medical experts have warned that patients should not initiate genetic tests on their own, particularly for coeliac disease and for the genes MTHFR and APOE, which are, respectively, associated with levels of folate and susceptibility to Alzheimer’s disease.

The Gastroenterological Society of Australia has recommended against genetic tests for coeliac disease because the relevant gene is present in about a third of the population and “a positive result does not make coeliac disease a certainty”.

Similarly, Human Genetics Society of Australasia Clinical Professor Jack Goldblatt said variants of the MTHFR gene were “very common in the general population [and] having a variant in the gene does not generally cause health problems”.

Additionally, Professor Goldblatt said that although the APOE gene was considered a risk factor for Alzheimer’s, “having a test only shows a probability, so people undertaking [the test] can also risk being falsely reassured”.

“Unnecessary genetic testing can lead to further unnecessary investigations, worry, ethical, social and legal issues,” he said. “In particular, we caution people to not initiate testing on their own. Genetic tests are best performed in a clinical setting with the provision of personalised genetic counselling and professional interpretation of test results.”

Related: Multiple gene testing: boon and dilemma

The recommendations are among 20 made by the Gastroenterological Society of Australia (GESA), the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists (RANZCR), the Human Genetics Society of Australasia and the Australasian Chapter of Sexual Health Medicine, as part of program being coordinating by the Choosing Wisely Australia campaign to improve the use of medical tests and treatments.

The advice includes cautioning women against self-medicating for thrush, improved use of radiation therapy to treat cancer, and careful use of colonoscopies.

Professor Anne Duggan from GESA said colonoscopies had a “small but not insignificant risk of complications”, and those undertaken for surveillance placed “a significant burden on endoscopy services”.

Professor Duggan said surveillance colonoscopies should be targeted “at those most likely to benefit, at the minimum frequency required to provide adequate protection against the development of cancer”.

The RANZCR said radiation treatment was “a powerful weapon” in the treatment of cancer, and half of those diagnosed with the disease would undergo radiation therapy.

But the College advised that such treatment should be provided within clinical decision-making guidelines, “where they exist”.

In particular, it has recommended sparing use of radiation to treat prostate cancer.

Dean of the College’s Faculty of Radiation Oncology, Dr Dion Forstner, radiation oncology might not be immediately required where prostate cancer is diagnosed.

“Patients with prostate cancer have options including radiation therapy and surgery, as well as monitoring without therapy in some cases,” Dr Forstner said.

Related: The scandal of prostate cancer management in Australia

The College also advised that while whole-breast radiation therapy decreased the local recurrence of breast cancer and improved survival rates, recent research had shown that shorter four-week courses of therapy could be equally effective “in specific patient populations”. It said patients and doctors should review such options.

The Chapter of Sexual Health Medicine made several recommendations, including advising against tests including herpes serology and ureaplasma in asymptomatic patients, and the use of serological tests to screen for chlamydia, because of frequent inaccuracy and the possibility of false-positive results.

In addition, it flagged concerns about the treatment of thrush.

Chapter President Dr Graham Neilsen said it was concerning that many women with recurrent and persistent yeast infections self-administered treatment, or were prescribed topical and oral anti-fungal treatments.

Dr Neilsen said it was important that patients had “good conversations” with clinicians about appropriate care.

“It is important to rule out other causes…such as genital herpes or bacterial vaginosis, so that other infection are not left untreated,” he said. “As well as the importance of ruling out other causes before commencing anti-fungal agents, inappropriate use of antifungal drugs can lead to increased fungal resistance.”

The 20 recommendations are the latest instalment in an ongoing program, coordinated by Choosing Wisely, in which 23 medical colleges and societies are working to improve the use of tests and treatments based on the latest evidence.

The process is separate from the Federal Government’s MBS Review, which is examining all 5000 items on the Medicare Benefits Schedule.

Latest news

- Sex linked to prostate cancer risk: study

- Antibacterial soaps to be reformulated in Australia

- The scandal of prostate cancer management in Australia

A review of maturity onset diabetes of the young (MODY) and challenges in the management of glucokinase-MODY

Case presentation

A 63-year-old lean female of Asian ethnicity was referred to our service in 2006 with a 12-year history of well controlled type 2 diabetes (T2D) in the absence of micro- or macrovascular complications. She had undetectable β-cell antibodies. Her fasting glucose levels were 6–7 mmol/L and her glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level was 7.3% (56 mmol/mol). She was previously diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) in three of five pregnancies, requiring insulin with the fourth pregnancy. All children were born without complication and of normal weight. Her father and five of six siblings were diagnosed with T2D. Over time, her management included diet and exercise, metformin 850 mg three times a day, modified release gliclazide 60 mg daily, and pioglitazone 45 mg daily. Ten years after referral, her HbA1c level was 7.6% (60 mmol/mol). She trialled basal insulin (glargine), but it was ceased as it was apparently ineffective. Her weight remained stable and her HbA1c levels showed little variation with escalating oral therapy. She developed postmenopausal osteoporosis and pioglitazone was ceased. Her daughter, who was also lean, was diagnosed with GDM during routine antenatal care. Given the autosomal dominant penetrance of diabetes in the family, she underwent genetic testing for maturity onset diabetes of the young (MODY) subtype 2 due to a glucokinase gene mutation (GCK-MODY), for which she tested positive. Our index patient also underwent genetic testing, and similarly tested positive for the same heterozygous mutation (aberrant splicing of intron 8c.1019+1G>A).

After being treated for more than 20 years, the patient was advised to cease treatment. She did so reluctantly, mainly due to the years of advice stressing the importance of treatment adherence. Her HbA1c level remained at 7.8% (62 mmol/mol) 3 months after treatment cessation. A 1-week continuous glucose monitoring study revealed fasting glucose levels of 7.5–8.4 mmol/L with the largest postprandial glucose excursion of about 3.0 mmol/L.

Literature search and sources

The sources used in this narrative review were obtained from original publications or reviews from groups renowned for their work in the definitions and genetics of MODY subtypes. Other publications were obtained from the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases and limited to English language; they were preferably recent publications (within < 10 years) and published in high impact journals. Information on specific genetic mutations and clinical phenotypes for the MODY subtypes were also obtained from the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man online catalogue (www.omim.org).

What is MODY?

MODY is a heterogeneous group of monogenic diabetes disorders due to pancreatic β-cell dysfunction.1,2 Patients with MODY have early onset of diabetes and typically lack features of insulin resistance or autoimmunity. The MODY subtypes, of which there are currently 14, were first identified in the 1970s.3–5 They have an estimated population prevalence of 1.1:1000, or about 1–2% of diabetes cases (Box 1) in white Europeans, but are present in every race and ethnicity.6

The three most common MODY subtypes are mutations of hepatocyte nuclear factor 1A (HNF1A, MODY3), HNF4A (MODY1) and GCK genes. The GCK mutation, known as MODY subtype 2 (MODY2), or more recently as GCK-MODY, constitutes 10–60% of all MODY cases (Box 2).2,9–11 Rarer mutations resulting in β-cell dysfunction are also considered as separate MODY subtypes, and include alterations to insulin promoter factor 1 (MODY4), HNF1B (MODY5), and neurogenic differentiation factor 1 (MODY6) (Appendix). Patients with MODY5 constitute 5% of all MODY subtypes; MODY5 has been named the “renal cysts and diabetes syndrome,” as it often encompasses other urogenital malformations, pancreatic atrophy and deranged liver function tests.

The reference list includes succinct and lengthier reviews for further reading on MODY subtypes7,10,12,13 and on GCK-MODY.2,7,14

MODY subtypes 1 (HNF4A) and 3 (HNF1A)

Although driven by different mutations, the clinical phenotypes due to alterations of the HNF4A (MODY1) and HNF1A (MODY3) are best regarded as similar entities, because the features and management are similar.7,10,15 It is believed that mutations in HNF4A and HNF1A, which function as transcription factors, specifically result in dysfunction of the α, β and pancreatic polypeptide cells within pancreatic islets, resulting in reduced or delayed insulin secretion in response to glucose.15,16 In general, both MODY1 and MODY3 may present with mild diabetes, although usually postprandial blood glucose excursions are greater than those seen in GCK-MODY (ie, ≥ 5 mmol/L).17 Clinical features of MODY3, in addition to those listed in Box 2, include young onset diabetes usually before the age of 25 years in at least one family member, not normally requiring insulin initially, with generally good glycaemic control with less insulin than anticipated, detectable C-peptide in the presence of a blood glucose level (BGL) of over 8 mmol/L, family history spanning at least two generations, postprandial glucose excursions over 5 mmol/L with or without normal fasting glycaemia, absence of pancreatic autoantibodies and glycosuria when BGLs are under 10 mmol/L (given the low renal threshold for glucose wasting).18 These patients usually have a profound response to low doses of sulfonylurea therapy,16,19 with one randomised cross-over trial demonstrating about a 5-fold greater response with gliclazide compared with metformin. Patients also typically lack features of metabolic syndrome or insulin resistance (eg, obesity, acanthosis nigricans, elevated or normal high density lipoprotein cholesterol, and normal triglycerides).10,12

In contrast, MODY1 (HNF4A) is much less common, although the clinical features are similar to MODY3 (HNF1A), aside from a later age at diagnosis and the lack of pronounced glycosuria. Patients with MODY1 also share sensitivity to sulfonylureas. Offspring of women with MODY1 are often born with macrosomia (> 4.4 kg in 56% of carriers) and there may be transient neonatal hyperglycaemia.8 Clinical suspicion should be raised when there is a strong family history of pronounced macrosomia, or less commonly, if there is diazoxide (a medication used to treat hypoglycaemia) responsive neonatal hyperinsulinism in the context of familial diabetes.

Like T2D, both MODY1 and MODY3 are progressive forms of diabetes, and insulin secretion reduces over time.13 It is expected that micro- and macrovascular complications should be screened for, especially retinopathy and nephropathy. Treatment with insulin may be needed in 30–40% of affected individuals.12 Mutations in HNF4A favourably affect lipid biosynthesis and are associated with a 50% reduction in serum triglyceride levels and a 25% reduction in certain serum apolipoproteins.10

MODY2 (GCK-MODY) is often misdiagnosed

Based on the frequency of diagnoses, referral rates and prevalence in the United Kingdom, it is likely that GCK-MODY is underdiagnosed (or misdiagnosed as T2D) as more than 80% of patients with GCK-MODY do not undergo genetic testing.20 The condition is driven by an inactivating, heterozygous mutation of GCK, the glycolytic enzyme that catalyses the conversion of glucose to glucose 6-phosphate, the initial step in the chain of glucose metabolism in the β cell, consequently required for the release of insulin.21 In GCK-MODY, GCK is abnormal and functions at a higher glucose sensing threshold, earning its reputation as the “glucose sensor” of the β cell and the hepatocyte.22

The clinical phenotype is asymptomatic, mild hyperglycaemia present from childhood, usually ranging from 5.4 to 8.3 mmol/L. Most patients have an HbA1c level of 5.6–7.3% (41–56 mmol/mol) if they are less than 40 years old, or 5.9–7.6% (41–60 mmol/mol) if they are more than 40 years old.23

Special groups

All children with fasting hyperglycaemia need exclusion of GCK-MODY

Chronic childhood hyperglycaemia is exceptionally abnormal and, therefore, GCK-MODY along with type 1 diabetes (T1D) are the major differential diagnoses to consider, as GCK-MODY is present in 10–60% of all children with fasting hyperglycaemia.2 One cohort study of 82 children with fasting hyperglycaemia (BGL, ≥ 5.5 mmol/L) and negative β-cell antibodies found a GCK mutation in 48% of the cases.24 The major discriminating features favouring T1D are the presence of one or more islet cell antibodies, more pronounced hyperglycaemia, requirement for insulin within 5 years of diagnosis, and a stimulated C-peptide level lower than 200 pmol/L, as these are usually lacking in GCK-MODY.1,25

Pregnant women with GCK-MODY may need treatment

Epidemiological studies suggest that GCK-MODY is present in 1–2% of mothers diagnosed with GDM, and it usually presents as asymptomatic, mild fasting hyperglycaemia.6 A lower body mass index (BMI, < 25 kg/m2) and a fasting glucose level greater than or equal to 5.5 mmol/L have sensitivity and specificity of 68% and 96%, respectively. It is estimated that among lean women with mild fasting hyperglycaemia, the number of women needed to test is 2.7 to detect a single case of GCK-MODY.6 With new diagnostic thresholds adopted in Australia defining the diagnosis of GDM (ie, fasting BGL, 5.1–6.9 mmol/L),11 it is likely that more cases will be detected incidentally. Treatment in mothers with a known GCK-MODY mutation is indicated only if the fetus has a confirmed normal genotype (via chorionic villus sampling or amniocentesis) or if there is sonographic evidence of accelerated fetal growth on ultrasound, since this likely reflects fetal hyperinsulinaemia as the fetus attempts to overcome maternal hyperglycaemia. Treatment is with insulin, which is normally ceased postpartum.2,26,27

Diagnosis

Mild, fasting hyperglycaemia in younger, slimmer patients

There are no distinct clinical features of GCK-MODY. Suspicion is based on the findings of persistently elevated fasting hyperglycaemia (5.4–8.3 mmol/L), HbA1c levels of 5.8–7.6% (40–60 mmol/mol), young age (< 30 years old), non-obese phenotype, post-prandial glucose excursions lower than 3 mmol/L, and autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance of diabetes.2,7 With respect to the latter, a strong clinical clue is that many relatives of patients with known GCK-MODY will have been diagnosed with prediabetes, T1D or T2D, yet they rarely require insulin despite being diagnosed for many decades, and seemingly few, if any, develop complications. Despite this, about 20% of family members with GCK-MODY receive treatment with oral hypoglycaemic therapy and a minority with insulin.4,28,29

Genetic testing is the gold standard

Confirmation of GCK-MODY is performed by molecular genetic testing using Sanger sequencing and requires 5–10 mL of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-treated blood. There are over 620 gene mutations identified throughout the ten pancreatic β-cell exons of the GCK gene in more than 1400 families.30 Samples can be sent to a number of laboratories.31,32 For example, one laboratory’s cost and processing time (4–8 weeks) will depend on whether the mutation is known to be due to a GCK mutation (cost ∼ $600) or either of HNF4A or HNF1A (∼ $800).2 A 16-gene MODY panel may also be requested for about $1145. Local laboratories can also perform the analysis for GCK mutations for $745 with a turn-around time of 4 weeks.32 Other mutations (ie, HNF4A, HNF1A) may be analysed by requesting a MODY 10-gene panel (next generation sequencing), inclusive of GCK gene mutation testing. A 4 mL EDTA blood sample is required (or 2 μg genomic DNA) and the cost is about $1100 with a 4-week turn-around time. As whole genome sequencing becomes more widely available, testing for heritable diabetes syndromes will become easier to access and new syndromes will be discovered (this information is current at the time of printing).

Testing patients greatly influences management

Because a diagnosis of GCK-MODY will significantly alter management, the clinician should be alert for suspected cases and refer suitable patients for genetic testing. However, as our case illustrates, in patients treated with diabetes medications for many years, the physician should discuss testing in an unbiased manner, without assuming that the patient will embrace a positive result that will allow them to cease therapy. If patients are amenable to ceasing treatment, as in our patient, this may cause significant stress and anxiety due to a feeling of guilt and perceived future morbidity. This is due to multiple previous clinical discussions with the patient stressing the importance of treatment adherence and tight glycaemic control. This is similarly important in patients with MODY3, in whom a positive diagnosis allows cessation of insulin and a switch to a sulfonylurea, which is likely to have been administered in a basal-bolus regimen or via an insulin pump for many years. Patients should be alerted that confirming a diagnosis of GCK-MODY not only significantly influences the number of investigations and reduces the treatment burden to them, but it also carries implications for relatives who may be undiagnosed, with offspring having a 50% chance of inheriting the gene.

To treat or not to treat

Arguments against treatment

With the exception of pregnancy, GCK-MODY has been regarded as a lifelong subtle abnormality in glucose homeostasis that is not progressive and shows little deterioration over time.16,33 This is in contrast to MODY3 (20–50% of cases), MODY1 (∼ 5% of cases)7 as well as T1D and T2D. GCK-MODY should therefore be considered a distinct clinical entity.2 As the fasting hyperglycaemia is often mild, varies little with time, and rarely results in the development of micro- or macrovascular complications, treatment is thought unlikely to change clinical outcomes.2,33 In a recent, large cross-sectional study involving GCK-MODY patients with a mean duration of 49 years, patients developed only mild background retinopathy when compared with healthy controls. Moreover, macrovascular complications developed in 4% of GCK-MODY patients versus 30% in patients with T2D, possibly reflecting the more favourable lipid profile in this condition.33

It is also known that the mild fasting hyperglycaemia in patients with GCK-MODY is resistant to oral diabetes therapy as well as dietary changes, due to the altered set point at which glucose homeostasis is maintained by the loss-of-function mutation of GCK.28 Therefore, treatment may not alter a patient’s glycaemic control or their trajectory towards developing complications as a result of mild fasting hyperglycaemia.

Arguments for treatment

As with the rest of the population, which is affected by genetic susceptibility, advancing age and rising rates of obesity, patients with GCK-MODY may also concurrently develop the metabolic derangements typical of T2D, such as progression of insulin resistance and β-cell failure.34 For example, one retrospective study of 33 patients with GCK-MODY over an 11-year period illustrated a small but significant deterioration in fasting (6.8–7.1 mmol/L) and 2-hour glucose levels (8.2–9.0 mmol/L), as well as decreases in insulin sensitivity when baseline and repeat oral glucose tolerance tests were compared.34 This was also associated with a mean increase in BMI from 19.2 to 22.3 kg/m2. More recently, it has been suggested that patients with GCK-MODY should be considered for treatment when the HbA1c level clearly and repeatedly exceeds 7.6 (60 mmol/mol).2,23 However, the question of whether to treat or not, based on a specific HbA1c level in patients with GCK-MODY, remains controversial; notwithstanding, HbA1c itself has limitations in predicting the development of microvascular complications.35

The verdict is divided

The decision to treat the patient should take into consideration the patient’s age, the current mild to moderate hyperglycaemia, the observation of postprandial glucose intolerance, the patient’s preference and the suboptimal HbA1c level, which may increase the risk of both micro- and macrovascular complications. This is in the context of an anticipated trajectory of deteriorating glycaemic metabolism that often accompanies advancing age and weight gain. This would naturally be weighed against the risks, cost and inconvenience of multiple investigations and the need for medical appointments, frequent self-monitoring of glucose levels, cost of glucose test strips, as well as patient anxiety.36 Furthermore, many patients may suffer from side effects from pharmacologic therapy; notwithstanding, weight gain, hypoglycaemia (especially if on sulfonylurea or insulin), gastrointestinal upset and vitamin B12 deficiency with metformin, as well as the adverse metabolic consequences to bone metabolism, bladder cancer risk and heart failure with thiazolidinediones, as in our index patient, should be considered. To date, there are no data on the efficacy of dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, or sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, in these patients. Therefore, a careful examination, by an attentive clinician, of the patient’s goals, quality of life, comorbidities and an estimation of benefit, should form the basis when considering the decision to treat.

Genetic testing is underutilised but may be cost-effective

The burden and cost, both personally and to the community, are difficult to estimate when considering the implementation of a screening strategy at a national level. A recent cost-analysis simulation of a one-time genetic screening test (with a cost of US$2580) for the three most common MODY subtypes (GCK, HNF1A, HNF4A) — which account for more than 90% of all MODY cases — within the first year of diagnosis, was undertaken in a hypothetical cohort of young individuals (aged 25–40 years old) with a diagnosis of diabetes.36 The study assumed that the prevalence of GCK-MODY was 6% (similar to other countries), and when diagnosed, patients with GCK-MODY received no treatment. The screening test yielded an average small gain of 0.012 quality-adjusted life years and an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of US$50 000.36 The cost-effectiveness extends to children, and arguably more so, with savings of about €1500 per year from time of diagnosis, as intensive treatment for presumed T1D in children is reduced to conservative management in the case of a positive diagnosis of GCK-MODY.37

It is not just MODY; diabetes genes are common in the general population

It is worth noting that not all genetic causes of diabetes can be ascribed simply to monogenic (single gene) mutations such as in MODY, or that there are a small number of rare genes inherited within generational lines that specifically affect an individual’s risk of developing diabetes. This approach, although clinically useful, is simplistic and may inadvertently overlook the fact that, on the whole, the population carries multiple, common genetic alterations in a single gene (ie, variants) that may collectively increase the risk of developing diabetes.38 A recent large analysis of exomes (protein-coding regions which comprise a fraction, 1–2%, of the whole human genome), from 6500 subjects with T2D matched to an equal number of healthy controls from five ethnic groups, has cast doubt on the evidence that rare or low frequency disease-associated variants affect the risk of developing diabetes. The authors note that most of the diabetes-associated genetic variants are quite common in the population.39

Conclusion

Despite the availability of genetic testing, there are a significant number of patient- and physician-related factors that may be prohibitive to uptake, including the perceived lack of possibilities for treatment (if coexistent MODY and T2D develop over time, many would argue that it may not change management if hyperglycaemia is mild; however, we believe that it makes a difference to management and monitoring) and prevention, cost implications of a positive diagnosis to patients, and lack of awareness of MODY as a diagnosis.40 These factors should all be discussed with the patient when considering genetic or genomic testing. The patient should be counselled regarding the treatment implications of a positive diagnosis, including the possibility that they may have not required the treatment they were prescribed many years prior. The points raised by this review will be increasingly relevant to the medical practitioner given the rapid development of genetic and genomic testing.

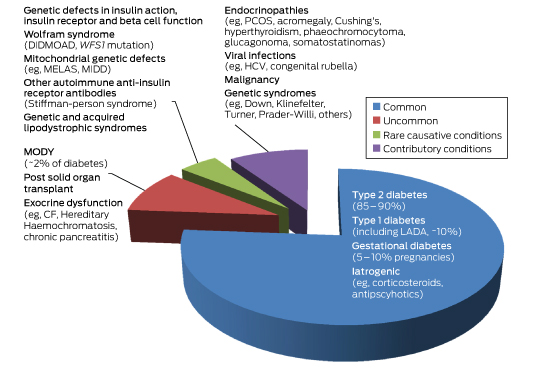

Box 1 –

Subtypes of diabetes according to relative prevalence

CF = cystic fibrosis. DIDMOAD = diabetes insipidus diabetes mellitus optic atrophy deafness. GDM = gestational diabetes. HCV = hepatitis C virus. LADA = latent autoimmune diabetes of the adult. MELAS = mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes. MIDD = maternally inherited diabetes. MODY = maturity onset diabetes of the young. PCOS = polycystic ovarian syndrome. WFS1 = wolframin gene.

Box 2 –

Prevalence, genetic and key clinical features of the common forms of diabetes and subtypes of maturity onset diabetes of the young (MODY)

|

|

Type 2 diabetes |

Type 1 diabetes |

Gestational diabetes |

MODY1 |

MODY2 |

MODY3 |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Prevalence |

1 in 13 people (∼ 870 000 in Australia) |

10% of all diabetes (∼ 170 000 in Australia) |

5–10% of all pregnancies |

∼ 5%* |

10–60%* |

20–50%* |

|||||||||

|

Causative mutation |

Multiple polymorphisms (eg, class II HLA genes) |

Multiple polymorphisms |

Multiple polymorphisms |

GCK2 |

HNF1A10 |

||||||||||

|

Clinical features |

Older (usually > 45 years), overweight or obese, often family history, insulin resistance |

Slim, family history of autoimmune disorders, usually childhood or early adolescence or adulthood (includes LADA) |

Older (> 40 years); pre-pregnancy obesity (BMI, > 30 kg/m2); family history (30%) and ethnicity; previous GDM; PCOS; macrosomic babies, diagnosed 24–28 weeks’ gestation |

Young age (< 25 years), strong family history of diabetes, absent antibodies, detectable C-peptide |

|||||||||||

|

Diagnostic glucose and HbA1c |

75 g OGTT: fasting BGL, ≥ 7 mmol/L; random or 2-h postprandial BGL, ≥ 11.1 mmol/L; HbA1c, ≥ 6.5% (48 mmol/mol) |

Similar to type 2 diabetes |

75 g OGTT: fasting BGL, 5.1–6.9 mmol/L;1-h, ≥ 10 mmol/L; 2-h, 8.5–11 mmol/L11 |

As with type 2 diabetes; postprandial glucose excursions, ≥ 5 mmol/L |

Fasting BGL, 5.4–8.3 mmol/L; postprandial glucose excursions, ≤ 3 mmol/L, HbA1c, 5.8–7.6% (40–60 mmol/mol) |

As for MODY1 |

|||||||||

|

Treatment |

Diet, exercise, OHG, injectable GLP1 RA, insulin |

Insulin |

Diet, exercise, metformin, insulin |

Respond to sulfonylureas, 30–40% apparent insulin-requiring |

None required (controversial) |

As for MODY1 |

|||||||||

|

Special features |

Progressive β-cell dysfunction with development of micro- and macrovascular complications |

Negative C-peptide and DKA without insulin (outside of honeymoon period), positive antibodies in majority to GAD, IA-2, ICA, IAA and ZnT8 |

Hyperglycaemia remits postpartum |

Glycosuria common; develop micro- and macrovascular complications as in type 1 and 2 diabetes |

Favourable lipid profile; lean; minimal or no micro- or macrovascular complications; minimal effect of treatment on glycaemic control |

As for MODY1; strong family history of macrosomic babies |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Denotes approximate percentage prevalence of all MODY subtypes. DKA = diabetic ketoacidosis. GAD = glutamic decarboxylase autoantibody. GCK = glucokinase gene. GDM = gestational diabetes mellitus. GLP1 RA = glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists. HLA = human leukocyte antigen. HNF1A = hepatocyte nuclear factor 1α gene. HNF4A = hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α gene. IA-2 = insulinoma-associated-2 autoantibody. IAA = insulin autoantibody. ICA = islet cell cytoplasmic autoantibody. LADA = latent autoimmune diabetes of the adult. OGTT = oral glucose tolerance test. OHGs = oral hypoglycaemic therapy. PCOS = polycystic ovarian syndrome. ZnT8 = zinc transporter 8 autoantibody. |

|||||||||||||||

more_vert

more_vert