Incorrect statement: In “Aboriginal community controlled health services: leading the way in primary care” in the 16 June 2014 issue of the Journal (Med J Aust 2014; 200: 649-652), there was an error in the “Workforce and training” section on page 651. The sentence “The Leaders in Indigenous Medical Education (LIME) Network has recently signed an agreement with the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation seeking to increase Aboriginal medical student placements in Indigenous primary health care settings with a view to increasing participation in and enhancing the effectiveness of the medical workforce” should have stated that the agreement was made with Medical Deans Australia New Zealand, not the LIME Network. The LIME Network is a project of Medical Deans that orchestrates many of their Indigenous health initiatives, but the partnerships between organisations are made at the Medical Deans level.

Preference: General Practice and Primary Care

333

A systematic review of the challenges to implementation of the patient-centred medical home: lessons for Australia

Australia’s first National Primary Health Care Strategy1 and resulting National Primary Health Care Strategic Framework2 initiated growing interest and development in our primary care sector, particularly general practice. Clinicians, governments and organisations are now actively searching for new approaches, models of care and business levers to support the primary care quality, efficiency and access gains sought. In December 2012, then Minister for Health Tanya Plibersek announced a focus on the patient-centred medical home (PCMH) as a model of interest.3 The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) has also been a consistent champion of the model, urging adoption of its elements as part of current reforms and calling for the federal government to fund and implement key elements in its 2013–14 Budget submission.4

The PCMH concept of care was introduced by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 1967, and was adopted in 2002 by the family medicine specialty. Four major primary care physician associations in the United States, along with other stakeholders, formed the Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative (PCPCC), and in 2007 endorsed the Joint principles of the patient-centered medical home.5 These include: access to a personal physician; physician-directed medical practice; whole-person orientation; care coordination and/or integration; quality and safety benchmarking through evidence-based medicine and clinical decision support tools; enhanced care availability after hours and via e-health; and practice payment reform. We used this definition of PCMH in our review because it concords strongly with the RACGP’s statement, A quality general practice of the future,6 endorsed by all general practice organisations nationally in 2012.

There is evidence that adoption of the PCMH model can improve: access to care;7–10 clinical parameters and outcomes;11–15 management of chronic and complex disease care;7–9,11,12,14–22 preventive care services (eg, cholesterol tests, influenza vaccinations, prostate examinations);9,10,12,13,17,18,20,23–26 and provide improved condition-specific quality of care14,15,18,19,22,27 and palliative care services.8 Data also indicate that the PCMH model can decrease the use of inappropriate medications,8,22,23 and significantly reduce avoidable hospital admissions and readmissions, emergency department use and overall care costs.8,14,22,28–31

While the PCMH model shows promise in transforming the primary care system into a more integrated and comprehensive model, studies report challenges and barriers to the implementation and adoption of this model. Before its potential can be achieved, more robust information is needed on the actual change process, challenges and barriers associated with implementation of this model.32,33

We undertook a systematic review to identify the major challenges and barriers to implementation and adoption of the PCMH model. The findings from this review will provide lessons for Australian primary health care reform and future PCMH initiatives in Australia.

Methods

A complete description of the methods is provided in Appendix 1.

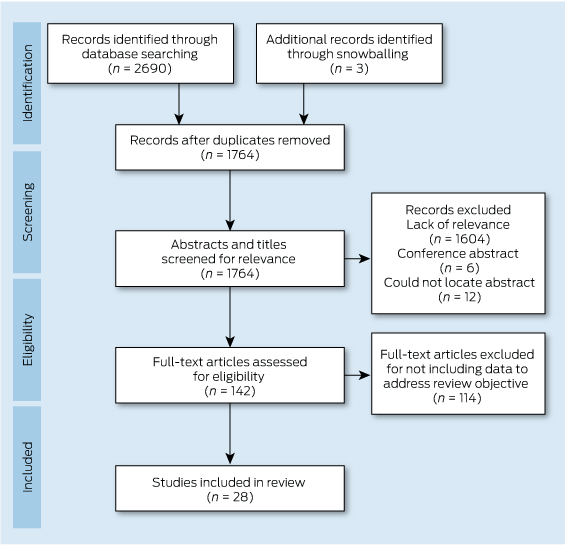

In December 2012, we searched the PubMed and Embase databases for studies published between January 2007 and December 2012 using the search terms patient centered medical home, patient centred medical home, medical home, or PCMH. Appendix 2 provides details of the search strategy. A snowballing strategy was used to identify other related citations through the reference list of all reviewed articles.

Abstracts were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: 1) published between 2007 and 2012; 2) in English; 3) reported information or data related to the review objective; 4) defined PCMH using the PCPCC Joint Principles, or at least mentioned some of its components.5 There were no restrictions on study design or country of study.

Articles included during the initial screening by either reviewer underwent full-text screening. One reviewer with expertise in the area reviewed the full text of each article and indicated a decision to include or exclude the article for data abstraction. We applied 10 quality criteria that were common to sets of criteria proposed by research groups for qualitative research (Box 1).34–36 Two reviewers independently assessed the quality of each study, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Data extraction and synthesis

A data extraction form was created by the investigative team to assist in systematically extracting information on the study design (type of study, methodology and setting) and key findings related to the review objective. One researcher with content knowledge in the area abstracted the data, while a second researcher reviewed the abstracted data alongside the original article to check for accuracy and completeness.

Thematic synthesis was used in three stages: the free line-by-line coding of data; the organisation of these “free codes” into related areas to construct descriptive themes; and the development of analytical themes.37 Data were configured at a study level using a top-down approach, which allowed individual findings from broad study types to be organised and arranged into a coherent theoretical rendering.38 Synthesis matrices allowed data to be recorded, synthesised and compared.

Results

The search strategy identified 2690 citations, of which 28 studies met the inclusion criteria (Box 2). All studies were from the US. This was not surprising, as the PCMH model is a North American model and the PCPCC Joint Principles of the PCMH definition we used as part of the inclusion criteria is from the US. Of the 28 articles, there were nine exploratory studies, 13 descriptive studies, and six experimental or quasi-experimental studies. All studies met five or more of the 10 quality criteria, and nine of the 28 studies met all 10 quality criteria. Descriptions of included studies (including type of study, method, setting and quality rating) are provided in Appendix 3.

This systematic review identified six key overlapping challenges and barriers to implementation and adoption of the PCMH model. These are presented below, and Appendix 4 includes a summary table of themes identified in each study.

Challenges with transformation and change management in adopting a PCMH model

Eleven studies discussed varying challenges and barriers to transforming to a PCMH model. Transformation calls for significant changes in the routine operations of practices, and these are difficult to achieve and require more than a series of incremental changes.16,27,39–44 Key requirements are: long-term commitment,17,39,43,45 local variation,17,39,45 a focus on patient-centredness,39,45,46 and support through reform of the larger delivery system to integrate primary care within it.17,27,40,47 Even with external payment reform, practices need extensive assistance coaching from external facilitators and expert consultants to transform to a PCMH.16,27,39,43

There were reported challenges41,43,44,48 relating to a shift in paradigm for individuals and practices, which required them to move away from a physician-centred approach towards a team approach shared among other practice staff.17,39,43,44,49 Transformation efforts were slowed or ceased by ineffective change management processes;39,50 lack of leadership,51,52 readiness for change, communication and trust;17,44,50–53 and culture.39,43,52,53 Misinformation or lack of understanding about the PCMH could lead to misunderstandings about what was being asked of practices and staff,41,45,53 causing resistance to change.39,43 Furthermore, practices without capacity for organisational learning and development, or what is called “adaptive reserve” (such as a healthy relationship infrastructure, an aligned management model and facilitated leadership), were more likely to experience “change fatigue”,17,41,43,44,50,54 and less likely to successfully implement the PCMH model.17,43,44

Difficulties with electronic health records

Implementing an electronic health record (EHR) with a clear, meaningful use, and which administers the principles of PCMH, has been a difficult task for primary care practices in transition.17,41,46,55 Implementation and use of an integrated EHR has proved to be more difficult than originally envisioned,27,39,41,43,52,53 requiring significant investment of time, effort, resources (eg, new equipment, training material) and money.39,41,44,52,54 Reported challenges related to setting up EHRs at practices, and providing ongoing technical support and resources to service.

There were also difficulties with functionality (eg, EHR could not provide data for population management; a disease registry was absent or extremely awkward to activate; and e-visits such as telephone, email or video consultations presented challenges), and use of EHRs (eg, accessing electronic records in a timely, easily digestible manner, and accuracy and reliability of information in the EHR).39,42,48,50,51 Furthermore, single-practice EHRs were reported as insufficient and a barrier to effective coordinated care,47 and the lack of interoperability of EHRs hindered collaboration between providers, crucial to the PCMH model.17,46,47,52,54

Challenges with funding and payment models

Sixteen studies reported challenges with the current funding models for PCMH. Most stated that current available funding and reimbursements were likely to be inadequate for the transitional costs and sustainability of the PCMH,39–42,45,49,50,54–59 and the essential functions of the PCMH are not supported by traditional fee structures.41,47,49,55,56 Many studies recommended that new payment structures and incentives for practices and providers be developed to support implementation and sustainability of the PCMH model.39,40,43,45,49,50,52,54–59

Insufficient practice resources and infrastructure

Eighteen studies reported barriers related to insufficient resources within practices to implement the PCMH model. These included lack of resources (eg, equipment, human resources, training material), structural capabilities, time and financial capacity to develop the necessary building blocks to transform their practice into a PCMH.17,45,51–53,59 Substantial support (including non-monetary support) and resources were required to implement change at the practice level.16,27,41,49,50,57,58,60 Smaller practices typically could not employ the same resources as larger facilities due to budget and resources constraints. Therefore, implementation at small practices was challenging due to lack of internal capabilities.21,41,42,44,61

Inadequate measures of performance and inconsistent accreditation and standards

There were several reported challenges relating to variations in PCMH standards, inadequate accreditation and measures of performance.16,17,39–42,45,47,56 Most tools developed to measure achievement of the medical home did not directly correspond to the seven Joint Principles that define the PCMH, and many of these principles were difficult to measure.45 Furthermore, accreditation does not yet capture all the key aspects required for a fully functioning medical home,16 and the criteria for evaluating PCMH were inconsistent.56 Establishing standards, measures and targets proved difficult.16,17,40,42

Discussion

In our systematic review, we found evidence of challenges and barriers to implementation of a PCMH model, including difficulties with transformation to a new system, change management issues, adopting EHRs and adapting payment models. Other challenges were inadequate resources, performance measurement and accreditation.

Our findings have significant importance for current Australian reform initiatives. The RACGP, as part of its 2013–14 Budget submission, called for the federal government to fund and implement key elements of the PCMH, as it “encapsulates the very definition of [future] general practice in Australia”.4 Evidence-based assessment of the barriers and enablers to such transition presented in this article is an essential step to effective implementation.

As in the US, primary care practices in this country are challenged by growing complexity of care, accreditation pressures, and perverse funding and reward systems. Clinicians and organisations are often on the receiving end of policy implementation that is top-down rather than bottom-up, and, as small businesses, struggle to adapt in the defined time frames.62,63 Our review also notes the importance of reform across the larger delivery system to integrate primary care change within it. It demonstrates the importance of a long-term and tangible commitment to change adoption at the practice level (strong “adaptive reserves”), with a focus on teamwork, leadership, high-quality communication, staff development and ongoing support for a culture of change. Appropriate practice resourcing for infrastructure and system support over the “transformation” period is essential, as identified in our National Primary Health Care Strategy.1,2

The literature also highlights the importance of practice and practitioner funding that promotes patient centredness, preventive health, and a focus on complex chronic disease support, case management and hospital avoidance. This is timely in the Australian context, as is the focus on EHRs that promote care coordination, quality and safety benchmarking, and clinical decision support.54

Finally, our findings suggest that reform initiatives should involve accreditation review, such that these frameworks reflect measures of performance and standards that match the key benchmarks of importance, with minimal administrative barriers. Such initiatives are in early development, with the RACGP and Australian Commission on Quality and Safety in Health Care partnering in a review of accreditation process and outcome.64

Our review had some limitations. The search strategy did not include grey literature, and unpublished evaluation studies or reports may have been missed. There could also be other challenges or barriers not reported in the reviewed publications. The review was limited to studies that used the Joint Principles,5 because this definition concords strongly with the RACGP’s A quality general practice of the future,6 but may have missed literature published outside this definition. Data abstraction from qualitative studies can be complicated by the varied reporting styles.65 Relevant study “data” were often not presented in the results section, but integrated into the discussion or recommendations. Hence, a second researcher reviewed abstracted data alongside the original article to check for accuracy and completeness. Furthermore, the synthesis of qualitative data is problematic and dependent on the judgement and insight of the researchers (interpretation bias).37,66,67 To limit this bias, two independent researchers were used in the synthesis process.

Our systematic review indicates that implementation of significant primary care change should be cognisant of several considerations, mostly at the practice–practitioner interface. It comes at an important juncture for Australian health care reform, with reviews into the personally controlled electronic health record and Medicare Locals, and recent ministerial statements regarding funding reform for chronic disease management likely to have a major impact on the sector. For policymakers, they underline the approach and resourcing required to effectively influence service delivery. For clinicians, they highlight the teamwork, commitment and practice infrastructure critical to success. Australian health care reforms demand “a stronger, more robust primary health care system”.2 Addressing documented barriers to change adoption relevant in the Australian context will be a critical evidence-into-policy initiative.

1 Criteria for assessing quality of studies34–36

- Aims and objectives clearly stated

- An explicit theoretical framework, study design and/or literature review

- A clear description of context

- A clear description of the sample and how it was recruited

- A clear description of methods used to collect and analyse data

- Attempts made to establish the reliability or validity of data analysis

- Inclusion of sufficient original or synthesised data to mediate between evidence and interpretation

- Use of verification procedure(s) to establish credibility

- Conclusions supported by results

- Relevance

Who’s responsible for the care of women during and after a pregnancy affected by gestational diabetes?

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is the strongest single population predictor of type 2 diabetes,1 and current Australian prevalence is 10%–13%, depending on the criteria used.2 Poor health outcomes extend to children of mothers who had GDM, due to increased risk of obesity and abnormal glucose metabolism during childhood, adolescence and adulthood.3

Antenatal lifestyle intervention is shown to improve short- and long-term maternal and infant health outcomes.3 In addition, it can effectively prevent type 2 diabetes among women who have had GDM.1 However, although some centres of excellence exist, in many cases, antenatal care is not delivered systematically.4

After their babies are born, women who have had GDM can be described as falling into a health care “chasm”.5 When these women leave hospital, their obstetricians and endocrinologists feel that their work is done. Lack of coordination between the hospital and primary care sectors can mean that no one assumes responsibility for the care of these women.

The opportunity to prevent or delay type 2 diabetes in this high-risk population through primary care was noted more than a decade ago.6 However, defined care pathways and coordination remain elusive; implementation of evidence has not occurred. In many cases, general practitioners may not be aware that the woman has had GDM, and may not have a clear pathway directing responsibility for follow-up care.

There is an urgent need to implement a widespread and coordinated approach to prevent progression to type 2 diabetes in this population. Rectifying this situation requires cooperation and collaboration between all care providers.

Antenatal care: navigating the new gestational diabetes landscape

The health care sector operates under guidelines with conflicting content and differing levels of comprehensiveness and professional endorsement (Box). The Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society (ADIPS) recently released revised consensus guidelines for testing and diagnosing GDM in Australia and New Zealand.7

Women with GDM are managed in hospitals because they are identified as having pregnancies at higher risk of adverse outcomes. The ADIPS guidelines recommend an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) for all women (unless already diagnosed with GDM in early pregnancy) at 24–28 weeks’ gestation.7 These guidelines were informed by several studies, including the Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study, which indicated a strong continuous association of maternal glucose levels with increased diabetic fetopathy.14

A change to testing protocols will be introduced in July 2014 and diagnostic criteria on 1 January 2015 (Aidan McElduff, Clinical Associate Professor of Medicine, University of Sydney and ADIPS President; personal communication). Concerns exist about their potential workload implications and evidence base.

Health service and pathology database analyses have resulted in equivocal projections of the potential workload increases; it is most likely that many will see a doubling of cases.2,15 Workload projections can be difficult, as true prevalence is not known, but it has been suggested that the increasing rate reflects the prevalence of abnormal glucose metabolism in the general population.16

In considering potential workload costs and changes, we need to consider the results from two well executed randomised controlled trials, which demonstrated that treatment of GDM can prevent adverse outcomes.17,18 For most women (80%–90%), GDM could be managed through dietary counselling delivered by a dietitian. In some centres, this proportion will be lower, depending on population characteristics. Medical nutrition therapy is a cornerstone intervention for women with GDM,19 and its appropriate delivery results in reduced insulin requirements and improved blood glucose control.19 However, systematic, evidence-based dietetic care of women with GDM does not occur in many centres in Australia.4 Australian health services require clinician leadership and commitment to partnership and change in (re)allocation of resources to support a multidisciplinary team in providing evidence-based care for improved maternal and infant outcomes.

Some clinicians raise concerns about diagnostic criteria changes based on observational study outcomes, but the previous diagnostic criteria were the product of an ad-hoc working party and lacked the strong evidence base that underpins the current criteria.20

Postnatal follow-up: who’s taking responsibility?

Australian guidelines recommend that all women who had GDM should undertake a 75 g OGTT between 6 and 12 weeks after delivery.7 International guidelines also highlight the importance of lifestyle modification, breastfeeding, birth control and risk counselling to improve health outcomes for these women and their children.12,13

The extent to which these recommendations are integrated into postnatal GP visits is not known, but some studies suggest diabetes testing is suboptimal.21 Self-report surveys of women with prior GDM indicated that about half of participants returned for OGTTs, but only a quarter in the appropriate period.21,22 The potential use of glycated haemoglobin testing instead of the OGTT appeals to many, but the approach may not change until it is approved on the Medicare Benefits Schedule.

Appropriate strategies to engage women in screening are paramount, as the motivation to manage a GDM diagnosis transforms to apathy once GDM resolves.23 Barriers to ongoing screening include a lack of awareness of the need for screening, difficulty attending screening with an infant, dislike of the OGTT process, being a mobile population, and inconsistent advice from health care providers about testing, lifestyle modification and risk.21–23 Findings from the United Kingdom suggest that health care professionals need to balance between reassurance of likely resolution of GDM and adequate information about potential progression to type 2 diabetes.23 Perception of risk is an important motivator; a lack of perceived risk of developing type 2 diabetes is common and can be related to timing, content and tone of messages.23,24

Prevention of diabetes in primary care

Which guidelines?

Three Australian guidelines exist for the follow-up of women who are at risk of type 2 diabetes (Box).7–9 Their core messages are similar, but they vary in several areas, diluting GP awareness and implementation. Beyond the timing of testing regimens, recommendations regarding lifestyle interventions to prevent type 2 diabetes progression are absent from the ADIPS guidelines, but the Diabetes Australia/Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) Diabetes management in general practice 2014–20158 and Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice (the “red book”; also distributed to GPs in Australia)25 outline diabetes management and dietary advice for diagnosed cases in general practice and for diabetes prevention.

Many similarities exist between the diet for GDM and diabetes prevention (ie, focus on low glycaemic index, low saturated fat, high fibre content). However, during a pregnancy complicated by GDM, there is a major focus on tightly controlled blood glucose levels, although appropriate diet quality for pregnancy requirements and gestational weight gain is also paramount. By contrast, diabetes prevention diets have a greater focus on weight reduction. Currently, there is no effort to explain to women who have had GDM the difference in approach.

A missed opportunity?

Although GPs view follow-up care as their role within the broader context of general health screening and promotion, this is often opportunistic.26 Advice from GPs is a powerful motivator for women to adopt lifestyle modification.27 However, GPs report not being well versed in guidelines for GDM follow-up care, potentially reflecting the lack of clarity in the literature and their varying knowledge and confidence in provision of lifestyle advice and interventions.28 GPs generally give appropriate exercise advice, but can be less clear about dietary or weight loss goals.26

These practices are reinforced by systems and process barriers of prioritisation of issues during a consultation, a lack of integration of recall tools and intervention resources in daily workflow, and uncertainty about responsibility for screening, as well as poor communication between secondary and primary care sector and fragmentation of pre- and postnatal care services.28

Right information, right people, right time

Clinical trials have demonstrated that lifestyle modifications with weight loss and moderate exercise can reduce the incidence of type 2 diabetes by up to 58% for people at high risk, with an impact still evident 8 years from the intervention onset and 4 years after the active intervention ceased.29 Real-world implementation in the Australian health care system has achieved 40% reduction in the risk of progression to diabetes.30

Agreement between and willingness to work in partnership with key stakeholders — such as ADIPS, Diabetes Australia, the RACGP and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians — is required for a collective approach to delivering diabetes prevention to this high-risk population.

However, despite convincing evidence about effective programs in Australia, postnatal support after a pregnancy with GDM is lacking and is without coordination. Interventions using technologies such as telephone, SMS and the internet have been trialled for diabetes care and may be useful in prevention. These must be underpinned by behaviour change theories and address barriers to making changes regarding future risk.23 Women have been identified as being receptive to messages several months after birth, which may align with “transition times” (eg, introduction of solids).23 Further efforts are urgently needed to develop lifestyle strategies that meet the specific needs of this group of women.

Diabetes Australia’s National Gestational Diabetes Register (NGDR), part of the National Diabetes Services Scheme, was launched in 2011 as a free service to women with a Medicare card to help those who have had GDM to manage their health and prevent progression to type 2 diabetes. One function of the NGDR is to send regular reminder letters to women and their GPs regarding diabetes checks (at registration, 12 weeks after birth, and annually thereafter). These reminder letters also include general information for the women and their families to help them continue a healthy lifestyle.

Although the NGDR outlines what testing to undertake, its potential to allow implementation and dissemination of a comprehensive, consolidated set of guidelines is perhaps underused. It could facilitate effective connection of women with a history of GDM with specific, effective, evidence-based lifestyle advice as well as clinical guidance for their GPs.

A call to action: the need for a collaborative approach

A clear pathway, developed between all stakeholders, with delineated roles and responsibilities to ensure that best-practice care is delivered along the continuum of antenatal, postnatal, interconception and longer-term care is required. Delivery of coordinated, effective programs is essential for this group of women. Without such clarity, and in the absence of a systems approach to care, we are failing to seize an opportunity to reduce the incidence of type 2 diabetes and promote the wellbeing of these women and their children. After a diagnosis of GDM, women view their GP as the most appropriate source of follow-up care,24 so it is imperative that GPs are given the right guidelines and education to advise these women about preventing or delaying progression to type 2 diabetes.

A comparison of current gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosis (GDM), treatment and follow-up guidelines

|

Details of guidelines |

|||||||

|

Guideline/society (country) |

ADIPS (Australia and New Zealand)7 |

Diabetes Australia and RACGP (Australia)8 |

Therapeutic guidelines: endocrinology (Australia)9 |

||||

|

Antenatal testing protocol |

Universal OGTT at 24–28 weeks; earlier if clinically indicated |

Universal screening at 26–28 weeks. Two-step approach recommended (GCT then OGTT). |

Universal GCT or OGTT at 26 weeks. Early screening if high risk |

— |

Universal OGTT at 24–28 weeks in women not previously diagnosed with overt diabetes |

At 24–28 weeks if the woman has any risk factors or earlier if GDM in a previous pregnancy |

Universal screening 24–28 weeks. Two-step approach preferred (GCT then OGTT) |

|

Timing of first postpartum follow-up visit |

6–12 weeks |

6–12 weeks |

6–12 weeks |

6–12 weeks |

6–12 weeks |

6 weeks |

6 weeks – 6 months |

|

Which test(s) for postpartum screening |

75 g OGTT |

75 g OGTT |

75 g OGTT |

FPG or 75 g OGTT |

75 g OGTT; not HbA1c |

FPG |

75 g OGTT |

|

Who with? |

— |

GP |

— |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Frequency of follow-up and recommended test |

Dependent on future pregnancy plans and perceived risk of type 2 diabetes, yearly OGTT if planning pregnancy. 1–2 yearly FPG (low risk); OGTT/HbA1c (higher risk) |

3-yearly; with FPG |

If postnatal test normal: annual fasting or random blood glucose or OGTT every 2 years and before subsequent planned pregnancies |

3-yearly, as above |

Minimum 3-yearly; with OGTT. If IFG or IGT, yearly |

Yearly; no blood test specified |

At least 3-yearly and before each pregnancy; not specified |

|

Other postnatal advice included |

No recommendations |

Increase physical activity, weight loss/healthy diet. Refer to dietitian and/or physical activity program. Preconception advice. |

Risk counselling for future type 2 diabetes. Lifestyle advice: diet/physical activity. Subsequent pregnancy: early screening 12–16 weeks repeated at 26 weeks. |

Weight loss and physical activity counselling as needed |

Women with a history of gestational diabetes found to have prediabetes should receive lifestyle interventions or metformin to prevent diabetes. |

Lifestyle advice: weight control, diet and exercise |

Lifestyle advice to prevent diabetes and cardiovascular disease should begin in pregnancy and continue postpartum. Encourage breastfeeding for at least 3 months postpartum. Provide risk and preconception counselling. |

ACOG = American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ADA = American Diabetes Association. ADIPS = Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society. CDA = Canadian Diabetic Association. FPG = fasting plasma glucose. GCT = glucose challenge test. HbA1c = glycated haemoglobin. IFG = impaired fasting glucose. IGT = impaired glucose tolerance. NICE = National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. OGTT = oral glucose tolerance test. RACGP = Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. UK = United Kingdom. US = United States.

Primary care of women after gestational diabetes mellitus: mapping the evidence-practice gap

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is the strongest population predictor of type 2 diabetes mellitus,1 with the cumulative incidence of type 2 diabetes ranging from 2.6% to 70% from 6 weeks to 28 years postpartum.2 Women who have had GDM are also at greater risk of a recurrence of GDM, cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome.3

General practitioners have a key role in providing postpartum and long-term preventive health care.4–6 While appropriate care and preventive health approaches in the weeks and months after childbirth provide an opportunity to improve health outcomes for mothers and infants, there are few comprehensive, evidence-based guidelines available.7 Women who have had GDM, and their infants, are even more likely to benefit from proactive care during this period,8 and there are several guidelines that cater to this group. For example, Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society (ADIPS) guidelines (current at the time of study)9 recommended an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) within 6–8 weeks (now 6–12 weeks10) of birth for women who had GDM. International guidelines also highlight the importance of lifestyle modification, breastfeeding, contraception and risk counselling to improve health outcomes for these women and their infants.11,12

There are several guidelines available to GPs when providing care after a GDM-affected pregnancy. Beyond the timing of testing regimens, recommendations regarding lifestyle interventions to prevent type 2 diabetes progression are absent in ADIPS, but the Diabetes Australia/Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) Diabetes management in general practice,13 and the RACGP Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice (the “red book”)14 outline diabetes management and dietary advice for diagnosed cases in general practice and for diabetes prevention.

What informs, and the extent to which preventive health practices are consistently integrated into, postpartum GP visits in Queensland, are unknown.

We aimed to evaluate GPs’ awareness, perceived knowledge, and use of GDM guidelines, and to determine the extent to which care within the first 12 months postpartum of a woman with a history of GDM is delivered according to guidelines.

Methods

We surveyed GPs who participated in a shared care arrangement with a south-east Queensland maternity hospital and undertook a retrospective chart audit of their patient records for women who were provided with maternity shared care between July 2011 and June 2012. Data collection occurred throughout 2013.

Eligible GPs were identified from the hospital’s database and invited by mail to participate in the study. A week after the mail-out, practices were telephoned to explain the study requirements. Hard to reach or undecided practices were contacted by a GP member of the research team (some, numerous times).

Consenting practices were sent a survey, medical chart audit form, instructions, and a reply-paid envelope. Each practice was contacted after 1 week to confirm receipt and reiterate the instructions. Two follow-up reminders were made to non-responding practices by telephone at 2-week intervals. A gift voucher valued at $100 was offered as an incentive for participation.

The GPs were asked to complete a one-page self-administered survey regarding postpartum management approach of women with a history of GDM. Before distribution, the survey was pilot-tested with two academic GPs independent of the study. Practice managers and/or nurses completed a one-page audit for each identified patient medical chart. The audit form was developed and revised based on a review of related literature, pilot testing at one practice, and review by two GPs independent of the study. The time frame of the audit covered a review of all GP consultations in the 12 months after the birth of the baby. The audit took about 10 minutes to complete. Patient names were not included on audit forms.

Ethics approval was granted by the Mater Health Services Human Research Ethics Committee.

Outcome measures and data analysis

Outcomes in the GP survey included: awareness and usefulness of specific practice guidelines in addition to their nominated guidelines, information on use and effectiveness of postpartum reminder systems for patient follow-up, and information on recommended timing and type of test for postpartum diabetes testing.

Audit outcome measures were checking and recording of preventive health indicators including: blood testing for diabetes, weight, body mass index, blood pressure, breastfeeding, and mental health status. Other outcomes, such as provision of advice on contraception, diet, exercise and relevant referral to specialist or allied health services were also assessed.

Survey and audit responses were entered into SPSS, version 22.0 (SPSS Inc) and checked twice for accuracy. Descriptive statistics were calculated and reported as frequencies or medians and ranges.

Results

General practitioner survey

We identified 38 GPs from 35 practices who shared care for a woman with GDM (n = 43) within the study period. Of these, 18 consented and completed the questionnaire (47% response rate). No other demographic information was collected from participants.

Box 1 shows GPs’ ratings of their familiarity with, and their perceived usefulness of, various guidelines. All GPs were familiar with the hospital’s GP maternity shared care guideline and rated it somewhat useful, useful, or very useful.

GPs had excellent knowledge of which diabetes test to order and timing of testing postpartum, with 100% stating that they order the OGTT and recommend testing within 6 to 8 weeks.

Fifteen of the 18 GPs used reminder systems to monitor postpartum women with prior GDM, with all but one GP indicating that it worked well. Although three GPs did not use a reminder system, all used record systems that had the capacity to set up reminders and recall. One GP indicated that they did not think the reminder system worked well, and stated it was because they had to remember to click “reminders” in the electronic medical record system as it did not come up automatically and thought it was easy to miss. Other barriers to the reminder system working well included patient non-compliance and the patient’s choice as to whether to attend their follow-up appointment.

Chart audit

Eighteen GPs completed one chart audit and one GP completed two. The total number of completed audits was 19 (19/43 audits). No pregnancies were recorded during the 12-month postpartum period.

The median number of times that a woman consulted her GP during the year after her pregnancy with GDM was five (range, 1–14). All women visited their GP at least once in the 12 weeks after the birth. All women were offered type 2 diabetes screening by their GP (18/19) or the hospital (1/19). The most frequently ordered test was an OGTT (15/19). Other tests ordered included glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) (1/19), fasting blood glucose level including full blood count (1/19) and electrolyte and liver function tests (2/19).

More than half (10/19) of the women had their OGTT ordered between 6 and 12 weeks (9/19 ordered between 6 and 8 weeks). The test was ordered earlier than 6 weeks for about one-third of the women (6/19), and after 12 weeks for two women. Of the women who had the OGTT performed, more than half had their OGTT between 6 and 12 weeks (10/19) (8/19 between 6 and 8 weeks). One woman had her test before 6 weeks, and three after 12 weeks. Five women did not have a test result recorded in their chart.

The chart audit indicated that each of the additional elements of care were recorded at least once in the 12-month postpartum period (Box 2). Body mass index, weight, diet, exercise and breastfeeding status were generally checked in the first 3 months, but not subsequently, while mental health status was checked within the first 3 months, and often had a second follow-up recorded. Blood pressure was checked regularly over the 12 months and contraception had more follow-up than other elements of care. Only one woman was referred to a dietitian.

Open-ended responses indicated each consultation generally focused on presenting symptoms or requests for tests or vaccinations.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that GPs who participated in a shared care program with a major maternity hospital have an excellent awareness of the timing and practices around the OGTT for women who have had GDM. GPs in our study were informed by a range of guidelines, and placed a great emphasis on guidance from the maternity hospital with which they collaborate. Knowledge, opinions, and practices regarding other postpartum preventive health indicators also reflect behaviour previously documented among maternity patients and the wider population,17,18 with blood pressure measurement, and discussions about contraception and infant feeding/breastfeeding occurring in most consultations. Mental health assessments and discussions occur less often, and measurements and discussion around lifestyle indicators occur much less frequently.

In previous research, GPs reported not being well versed in guidelines for GDM follow-up care, potentially reflecting the lack of clarity in the literature and their varying knowledge and confidence in provision of lifestyle advice and interventions.19

Further, although GPs viewed follow-up care as their role and within the broader context of general health screening and promotion, it was often opportunistic.19 We found that women generally presented for another issue, rather than a post-GDM check-up, resulting in a conflict in priorities. Consequently, the discussion about preventive health measures, particularly within the context of limited consulting time and the current remuneration system, is often overlooked. These results are partially reinforced by previous findings that GPs generally give appropriate exercise advice, but can be less clear about dietary or weight-loss goals,19 despite the fact that advice from GPs is a powerful motivator for women to adopt lifestyle modification.20

The need for a systematic approach to delivery of care to women after a pregnancy affected by GDM is recognised.21,22 Another article in this supplement calls for a clear pathway and one recognised and endorsed guideline to ensure best-practice care is provided to this high-risk group by all health care professionals.21 A review of the topic noted that systems-based approaches are associated with a larger potential impact to improving testing rates, and appear easily generalisable.22 Essential elements of a system to increase a woman’s engagement with her GP in the postpartum period should be aligned with other key milestones in the postpartum period23 and involve proactively contacting patients.22 Diabetes Australia’s National Gestational Diabetes Register, part of the National Diabetes Services Scheme, already functions to remind women and their doctors of relevant testing and lifestyle modifications, and could be adapted to provide further clinical guidance to GPs.21

A targeted approach to translate guidelines into practice is required to complement the systemic approach to care, as awareness and dissemination of guidelines alone does not change practice.24 The assessment of influencing factors and implementation and evaluation design must be theory-driven.25 The implementation should address the knowledge gaps in guideline identification and content, and other barriers, such as time constraints and recall of new protocols. Recognition of other locally relevant barriers and enablers that facilitate implementation of clinical guidelines should also be identified and explored.

Despite our survey and chart audit returning a 47% response rate, slightly below the return rate noted for primary care surveys,26 it reflects the challenge of research in the context of the heavy workload of many practices. The chart audit demonstrated quite clearly the concerted efforts of many GPs to provide best-practice care to women in the postpartum period. Another limitation of this study is capping the analysis of the provision of preventive health care at 12 months. A longer follow-up period could have provided a stronger insight into the delivery of care to this patient cohort.

Our research provides new knowledge around care provided to women by GPs in the 12 months after birth. We have demonstrated that GPs from our surveyed cohort knew guidelines around the timing and type of test for women who have experienced GDM in their pregnancy, and our chart audit has demonstrated that this knowledge is translated into practice. Less ideal were the practices and beliefs around the provision of other preventive health behaviours. This problem exists due to the absence of a systems approach to care, resulting in a lost opportunity to work systematically to reduce the incidence of type 2 diabetes and promote the wellbeing of these women, who are at high risk of chronic disease, and their infants.

1 General practitioners’ ratings of their awareness and usefulness of various guidelines (n = 18)*

|

Guidelines or approaches used |

Usefulness of the guideline/approach |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Not familiar |

Not useful |

Somewhat useful |

Useful |

Very useful |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Diabetes management in general practice: guidelines for type 2 diabetes 2012/13 (Diabetes Australia)13 |

2/16 |

0 |

5/16 |

4/16 |

5/16 |

||||||||||

|

14/16 |

0 |

0 |

1/16 |

1/16 |

|||||||||||

|

ADIPS consensus guidelines for the testing and diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus in Australia (Australasian Diabetes in Pregnancy Society, 2013)10 |

8/17 |

0 |

0 |

4/17 |

5/17 |

||||||||||

|

Gestational diabetes mellitus – management guidelines (ADIPS; 1998, 2003)9 |

9/16 |

0 |

3/16 |

2/16 |

2/16 |

||||||||||

|

Hospital discharge summary |

0 |

1/18 |

7/18 |

4/18 |

6/18 |

||||||||||

|

Hospital general practice maternity shared care guideline (August 2012) |

0 |

0 |

3/18 |

5/18 |

10/18 |

||||||||||

|

Other (please specify) — Diabetes in pregnancy: women’s experiences and medical guidelines16 |

1/1 |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Missing responses were excluded from totals. |

|||||||||||||||

2 Preventive health care indicators recorded as discussed by a general practitioner with a woman who had gestational diabetes mellitus within 12 months of birth (n = 19)

|

Body mass index recorded |

Weight recorded |

Blood pressure recorded |

Mental health assessed |

Breastfeeding status recorded |

Contraception discussed |

Diet discussed |

Exercise discussed |

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Number of women with health care indicator recorded |

4 |

6 |

14 |

7 |

18 |

15 |

9 |

8 |

|||||||

|

Median time of first discussion, weeks postpartum (range) |

2.5 (1–6) |

2.5 (1–20) |

2.0 (1–37) |

6.0 (1–31) |

2.0 (1–13) |

7.0 (1–33) |

7.0 (2–27) |

6.5 (2–27) |

|||||||

|

Number of women with health care indicator recorded more than once in the 12-month period |

2 |

3 |

8 |

3 |

10 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

|||||||

Copayments for general practice visits

To the Editor: While the points made by Del Mar1 would have their proponents and opponents, it is a pity that the debate is constrained by Australia’s obsession with universal fee-for-service medical care.

Surely we should be rational and have “horses for courses”. If there are socioeconomic areas (whether urban or rural) where most people would be seriously deterred from seeing a general practitioner by a $6 (or $7) copayment, is it reasonable or logical for medical practice in those areas to be remunerated on a fee-for-service basis?

Fee-for-service has a purpose — to make patients bear some responsibility for their use of medical services.

Such impoverished areas could instead be served (and in many countries are served) by salaried GPs or by GPs paid per patient on their books (capitation).

Health insurance mitigates the fee-for-service burden on patients but, if excessively generous, leads to the “moral jeopardy of insurance”, where the patient spends at will, knowing that the insurer is picking up the tab.

Is it not time for Australia to give up this obsession with universal fee-for-service? It has proven to be unbearably expensive for the nation, aggravated by Medicare’s and health funds’ (backed by federal subsidy) re-imbursements.

Let’s find a rational solution to our nation’s budgetary woes, not an emotional one.

Health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: handle with care

This special Indigenous health issue of the MJA features stories of successful health care services and programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. As we seek to build on the wealth of experience outlined, it is worth considering what these contributions have to tell us about the characteristics and value of effective Indigenous health services.

It is more than 40 years since the founders of the first Aboriginal health service recognised a need for “decent, accessible health services for the swelling and largely medically uninsured Aboriginal population of Redfern [New South Wales]” (http://www.naccho.org.au/about-us/naccho-history#communitycontrol). There are now about 150 Aboriginal community controlled health services (ACCHSs) in Australia: services that arise in, and are controlled by, individual local communities, and deliver holistic, comprehensive and culturally appropriate health care. Panaretto and colleagues (doi: 10.5694/mja13.00005) describe how these services have led the way in high-quality primary care, as well as enriching both the community and the health workforce.

With the ACCHS model setting the standard, the values of responding to community need, Indigenous leadership, cultural safety, meticulous data gathering to guide improvement, social advocacy and streamlining access have gradually been adopted in other health care settings. The progress of the Southern Queensland Centre of Excellence in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care (a Queensland Health-owned service also known as Inala Indigenous Health Service), is an example (doi: 10.5694/mja14.00766). Among the hallmarks of the service’s vitality are its ever-increasing patient numbers, research output, building of community capacity, expansion into specialist and outreach services and multidisciplinary educational role.

The East Arnhem Scabies Control Program, described by Lokuge and colleagues (doi: 10.5694/mja14.00172), is a dramatic example of innovation inspired by local need. This part of Australia has the highest rates of crusted scabies in the world, and the program involved collaboration between two external organisations, an ACCHS and the Northern Territory Department of Health. Importantly, it was able to be integrated into existing health services and largely delivered by local health workers, using active case finding, ongoing cycles of treatment and regular long-term follow-up.

Mainstream health services are now beginning to take the lead from Indigenous-specific ones. For example, the repeated observation that Indigenous men and women with acute coronary syndromes are missing out on interventions and are at risk of poor outcomes inspired a working group from the National Heart Foundation of Australia to develop a framework to ensure that every Indigenous patient has access to appropriate care (doi: 10.5694/mja12.11175). The framework includes clinical pathways led by Indigenous cardiac coordinators, and it is already producing results.

There is growing evidence for the value of sound and accessible primary care for Indigenous Australians. A letter by Coffey and colleagues (doi: 10.5694/mja14.00057) highlights the significant progress towards closing the mortality gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians in the NT since 2000, temporally associated with investment in primary health care. A research report from Thomas and colleagues shows that patients with diabetes living in remote communities were more likely to avoid hospital admission if they accessed regular care at one of the remote clinics, saving both lives and money (doi: 10.5694/mja13.11316).

While the diversity of health services and the evidence of effectiveness is indeed something to celebrate, it is a fragile success. In their editorial, Murphy and Reath (doi: 10.5694/mja14.00632) highlight the need for sustained, long-term financial investment in primary health care services for Indigenous Australians and the uncertainty arising from changes to health care funding and Indigenous programs announced in the recent federal Budget (http://nacchocommunique.com/category/close-the-gap-program). The detail of how funding will be reallocated with the “rationalisation” of Indigenous programs has not yet fully emerged. Analysis indicates the cuts over 5 years include $165.8 million to Indigenous health programs, which will be added to the Medical Research Future Fund. New spending on Indigenous programs includes $44 million in 2017–18 for health as part of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet Budget (Adjunct Associate Professor Lesley Russell, Menzies Centre for Health Policy, University of Sydney, NSW, personal communication).

Changes to primary care funding are of particular concern. Knowing, as they do, the importance of removing barriers to access, there is increasing public discussion that ACCHSs and large Aboriginal medical services will not pass on the proposed $7 copayment to patients (http://theage.com.au/act-news/health-service-facing-budget-blackhole-by-not-charging-copayment–20140527-zrpb7.html). This will result in a decrease in funding to services that provide vital programs and deliver high-quality outcomes. The government has stated that everyone should share the deficit burden, yet the copayment has only been targeted at general practitioners and not specialist consultations. Is this fair and equitable?

It seems ironic that this threat to access and resourcing has arisen just as it is emerging that our investment in primary care for Indigenous Australians has been well made. In an Australia where many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people still face significant socioeconomic and health disadvantage, the need for “decent, accessible health services” is greater than ever.

From vision to reality: a centre of excellence for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care

A centre for high-quality, culturally safe primary care, research and teaching, and improved access to specialists is open for business

Access to medical services continues to be problematic for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. There are barriers relating to availability, affordability, acceptability and appropriateness, and the latter two are particularly relevant in urban areas.1 National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) models of care redress these barriers.2 Five years ago, we described how the Inala Indigenous Health Service (IIHS), a Queensland Government-funded primary care service in Brisbane, had adopted the key principles underpinning the NACCHO models of care and established a culturally secure health service with an associated increase in the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients from 12 in 1994 to over 3000 in 2008.3 Here we report on the expansion and maturation of the IIHS into the Southern Queensland Centre of Excellence in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care (CoE).

The CoE aims to improve access to health care and health outcomes by providing high-quality, integrated primary and secondary care, training for the next generation of health care professionals, a research agenda focusing on chronic disease and health service delivery, and outreach services to areas where access to primary care is problematic.

In 2010, the Queensland Government provided $7 million to construct a purpose-built clinic. At the June 2013 opening, the Queensland Minister of Health announced a further $10.5 million for Stage 2 to accommodate existing allied health personnel (a dietitian, social worker and psychologist), research team, and community engagement team. In partnership with the University of Queensland, Stage 2 will also incorporate dental care facilities.

By May 2014, we had over 10 000 adult patients registered with our Inala clinic, with 3500 attending regularly (at least three visits in the past 2 years). In the 12 months before May 2014, there were 14 070 general practitioner consultations at the main clinic, plus an additional 2182 consultations at our two outreach clinics. Seven visiting specialists provide between one and four clinics monthly, significantly enhancing access to specialist services.4 Exercise stress tests and echocardiograms are done at Inala, with patients who need follow-up angiograms at the local public hospital now being more likely to attend for the procedure, possibly because of the established relationship with the cardiologist. Three new visiting specialists, a podiatrist and a physiotherapist will begin working at the CoE in July 2014. Patients appreciate the specialists coming to Inala rather than having to attend hospital-based specialist outpatient clinics.

The CoE research agenda has three major themes: increasing our understanding of our patients and their health status; describing and evaluating how we care for our patients; and trialling new health care delivery approaches. The Inala Community Jury for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research (our community research advisory group) reviews all our research to ensure the cultural appropriateness and community relevance of the topic and approach. We are cognisant of the troubled history of research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples5 and always try to minimise the burden of participation by using administrative data where possible — for example, computerising health check templates, enabling patient information to be stored in their medical records and, for consenting patients, in a research database.6

In addition to general practice and specialty registrars and medical and nursing students, we also provide placements for allied health students, public health undergraduate students, and Aboriginal health worker trainees. Each student or registrar is orientated to the community engagement activities of the CoE and to the local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community with the aim of improving their understanding of urban Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care.

We have established an expert health team that delivers culturally sensitive primary health care to Cunnamulla, Western Queensland every month. The all-Aboriginal team consists of a general practitioner, two nurses and administrative staff, accompanied at times by either an endocrinologist or a cardiologist. We also provide an outreach “Mums and Bubs” clinic in an underserviced outer suburb of Brisbane four days weekly, and a weekly clinic at a local independent girls school in Brisbane that provides secondary school education, vocational training and mentoring for students who haven’t succeeded in traditional educational models.

In 2009 we wrote that new, innovative strategies were needed to improve health outcomes and life expectancy for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.3 The CoE has broken down access barriers by providing acceptable, accessible and appropriate primary-level and secondary-level care. While its governance model is not that of a community controlled health service, the CoE mirrors the community controlled sector in the philosophies and principles that inform the clinical care, community engagement, teaching, research, leadership and its overarching vision. In summary, the CoE is striving towards providing high-quality, culturally safe clinical care to underserved Indigenous communities, and making a positive contribution to the Indigenous health workforce and research base.

Reports indicate that changes are needed to close the gap for Indigenous health

To the Editor: The summation by Russell that “the inescapable reality is that current primary care interventions are not working”1 overlooks evidence of significant improvements in the Northern Territory. The latest “closing the gap” report indicates that the Indigenous mortality gap in the NT should close within a generation.2

Mortality among NT Indigenous adults has declined by a third since 2000.2 We attribute this positive outcome primarily to effective use of primary health care funding, which has been progressively increased and equitably distributed, since 2001. This money has funded universally adopted e-health solutions and NT key performance indicators, which drive continuous quality improvement initiatives. These are backed by common clinical guidelines, with increasing adherence rates, that are used in all Aboriginal primary health care clinics.3

The statement “ACCHOs [Aboriginal community controlled health organisations] have had little influence on the mainstream health system”1 neglects experience in the NT, where the ACCHO sector is a co-owner of the NT Medicare Local and remains a critical driver in the NT Aboriginal Health Forum (NTAHF). Now in its 15th year, the NTAHF has secured government support for community control as the preferred model for delivering Aboriginal primary health care. The ACCHO sector is also a leader in developing and using clinical guidelines, mental health services, e-health, and continuous quality improvement programs. National policy should support the expansion and enhancement of Aboriginal community controlled primary health care services.

Reports indicate that changes are needed to close the gap for Indigenous health

In reply: The letter from Coffey and colleagues helps make my case that a major role for Aboriginal community controlled health organisations (ACCHOs) in providing health care to Indigenous communities makes a real difference in the effectiveness and efficiency of service delivery. However, we cannot be certain that the progress made in reducing Indigenous mortality rates in the Northern Territory is the result of better health care; it may reflect improvements in the social determinants of health, such as education, housing and community violence.

Hospital data highlight that success is still a long way off. The ratio of Indigenous to non-Indigenous aged-standardised hospital separations for the NT is 7.9, compared with 2.5 for all jurisdictions.1 There is a clear relationship between the number of primary care visits and hospitalisation for Indigenous residents of the Territory who live in remote communities. For patients with diabetes, ischaemic heart disease and renal disease, around 22 to 30 primary care visits a year are needed to reduce hospitalisations to a minimum.2 That is why an increased role for ACCHOs is one of the keys to closing the gap.

Engaging Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men in primary care settings

To the Editor: It is well recognised that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men are one of the most disadvantaged population groups in Australia in terms of physical wellbeing.1 Annual Medicare Benefits Schedule health assessment items are essential tools to help Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men (and women and children) receive primary health care matched to their needs, as well as opportunities for preventive health care and education.

A growing body of evidence suggests that erectile dysfunction (ED) coexists with, or is a clinical marker for, other common life-threatening conditions, such as coronary heart disease and type 2 diabetes, due to shared underlying neurovascular mechanisms.2 Indeed, the relative risk and severity of coronary artery disease appears to be higher for young men reporting ED.3 Despite this, discussion with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men about sexual health is often lacking. In such population groups at risk of chronic disease, the opportunity to assess erectile function may present a window of opportunity to identify and better manage life-threatening disease.2

To engage these men in sexual health discussions, a greater focus on culturally appropriate health services is needed. Cultural competency training is essential to overcome the barriers affecting how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men access health services (Box 1). However, the sex-specific nature of some barriers and the impact of traditional and cultural roles on health service access pathways for men often require further attention, particularly for more culturally sensitive issues such as sexual health.

There are many other strategies and practical approaches that health services and primary health care professionals can implement to better engage Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men in positive and broader help-seeking behaviour and health service access (Box 2).6 Being able to implement such strategies may be an indirect reflection on the ability of health services to support cultural respect and provide culturally safe health care more broadly.

1 Factors influencing health service access and help-seeking behaviour for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men4,5

Societal

- Illness-related stigma

- Sex-specific differences in health

Cultural

- Traditional gender-related law, masculinity and gender roles

- Language barriers

- Beliefs around causation

Logistical

- Lack of transport

- Conflict of appointment times with other family and community priorities (eg, ceremonies)

Health system

- Limited access to specialist services and/or treatment

- Complicated referral process

- Too few (male) health professionals, leading to patients seeing many different doctors

- Medical terminology and jargon

Financial

- Difficulties in meeting health service costs

Individual

- Knowledge or perception of the nature of the illness

- Previous illness experience

- Low prioritisation of preventive health care

- Lack of understanding and embarrassment

- Low self-esteem and confidence

2 Examples of culturally appropriate strategies for engaging with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men about sexual health issues

- Provide a safe, private and comfortable environment that supports open and free dialogue

- Men may not open up in the first consultation — take time to build trust and respect

- Encourage men to have annual health assessments and incorporate sexual health questioning into these

- Make the clinic conducive to talking about sensitive issues; for example, a model of the male pelvis in the consulting room might help initiate discussion

- If only female health care providers are available, approach gender-specific issues in a sensitive way and use male Aboriginal health workers for advice or, if not urgent, refer to a male general practitioner

more_vert

more_vert