Population screening of young children has been proposed to detect early developmental delay and behavioural difficulties, enabling early intervention and prevention of long-term physical and mental health problems.1–3 The Healthy Kids Check (HKC) is an Australian Government initiative to assess 4-year-old children for physical developmental concerns, introduced as a one-off Medicare-funded assessment in 2008. Although now rescinded, the National Health and Medical Research Council review of childhood screening and surveillance did not recommend screening, instead proposing surveillance (meaning “following development over time”).4 The HKC is classified as screening rather than surveillance, because it is a one-off check. With over 282 200 4-year-olds in Australia in 2010,5 this represents a significant health investment.

The HKC is usually administered by general practitioners, who are well placed to identify and subsequently manage potential problems. Children with possible problems may be referred to specialists for confirmation and management. Although implementation of the HKC varies from practice to practice, there are six mandatory screening items: height and weight, vision, hearing, oral health, toileting, and notation of allergies.6

Effective strategies to identify and confer benefits to child health outcomes are paramount. However, few screening implementation studies have assessed child health outcomes.7 Rather, many have assessed changes to screening rates, identification of potential problems and referrals.8–10 These are surrogate end points; they do not evaluate the effectiveness of screening intervention outcomes. Ideally, to assess the clinical impact of screening programs on child health, researchers should track developmental and health outcomes of children whose screening test results are positive or negative.

There have been two reviews on the effectiveness of the mandatory screening components of the HKC. They found insufficient evidence for the effectiveness of most components, evidence for some components, and evidence of ineffectiveness for the remainder (Appendix 1).3,11 There were plans to expand the HKC to include social and emotional developmental problems and to reduce the screening age from 4 to 3 years in 2014.12 Since the first announcement of the changes, the reduced age has been maintained, but the composition of the new HKC is now unclear. Policy decisions about the expansion of the HKC, and even its original form, are not well informed by data on its efficacy or efficiency. This may reflect the assumption that early detection leads to early treatment and therefore that screening is beneficial. However, screening can be harmful as well as beneficial.13 Screening is effective if (i) the screening test has good sensitivity and specificity;14 (ii) effective early intervention is equitably available and accessed;15 and (iii) early interventions yield better long-term outcomes than those provided later.16

Our study is the first evaluation of the HKC. We aimed to determine how many children had health problems identified by HKC screening and how many of these had their clinical management changed.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective audit of 557 medical records from two Queensland general practices that provided the HKC to children between January 2010 and May 2013 (Box 1). We identified appropriate records by matching dates of birth and Medicare item numbers 701, 703, 705 and 707 (time-based HKC consultations with GP input). We read relevant files from the date of file commencement until either 9 March (Practice 1) or 2 June (Practice 2) 2013. By reading entire files and extracting data related to all child health problems noted by the GP, we were able to match specific health problems to time of detection in relation to the itemised, one-off HKC. Data extracted included child health problems detected before, during and after the HKC. For some children, some health problems were detected twice. In these cases, we coded the first detection: problems detected before and again during, and those detected before and again after, the HKC appointment were coded as “before”; and problems identified during and again after the HKC were coded as “during”.

We recorded any child health problems described in the consultation notes section of the medical records and matched these to the HKC components. These are described in Appendix 2. In the event of a review scheduled or a referral made as a result of the HKC, outcome data from review notes, letters or referrals were also extracted. Two authors (B R and K V) conducted double data extractions for about 10% of the sample to identify potential discrepancies and to discuss and resolve these before independently extracting and entering the remaining data. Data were entered into Microsoft Excel spreadsheets. Discrepancies (predominantly data entry errors) were reconciled by another author (L M) before analyses. Our a priori setting of clinical significance was a minimum change of 6% in clinical management for the program to be effective. This was arbitrary, and represents about one child per GP per year benefiting from the HKC. Study approval was granted by the Bond University Human Research Ethics Committee (RO1568).

Results

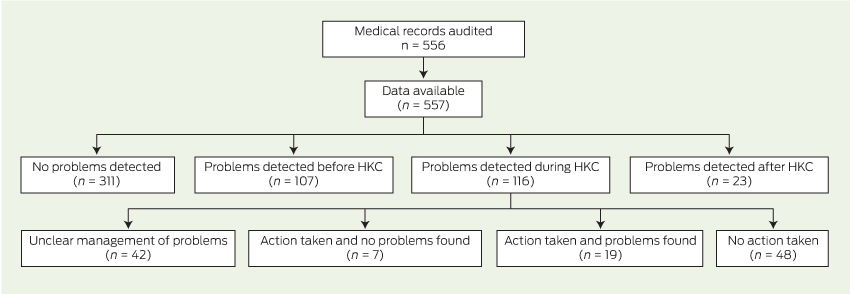

Of the total number of children in our sample, over half (331/557, 59%) had no problems in their health or development noted in the medical record at any stage; 116/557 (21%) had problems identified during the HKC; 107/557 (19%) had problems detected before the HKC; and 23/557 (4%) had problems detected after the HKC (Box 2).

Of the children with problems identified during the HKC, 19/557 (3%) were referred or reviewed and then confirmed with appropriate change in clinical management; 7/557 (1%) were managed or referred, with no problems confirmed; 48/557 (9%) had no action taken; and the remaining 42/557 (8%) had uncertain outcomes (Box 3). Therefore, up to 11% (61/557 [19 children with confirmed problems and 42 children with unclear or missing data]) of children may have had problems identified by the HKC and managed appropriately, but most of these children had unclear file notations.

Child health concerns detected by GPs

Overall, 347 problems were identified in 246 children (Box 2). The three most identified developmental problems were speech and language (77/347, 22%), hearing (51/347, 15%) and anatomical concerns (42/347, 12%).

Of the problems detected before the HKC appointment, the most common were speech and language (41/174, 24%), anatomical concerns (32/174, 18%) and hearing (23/174, 13%). Problems identified during the HKC included mandatory components and other problems detected during the check. Problems from the mandatory components were independent toileting (22/144), hearing (21/144) and vision (21/144) (15%, respectively), oral health concerns (10/144, 7%) and concerns regarding height or weight (4/144, 3%). Other problems commonly identified during the HKC involved speech and language (29/144, 20%), behaviour (13/144, 9%), anatomical concerns (8/144, 6%) and cardiac problems (5/144, 3%). No allergy notations were extracted from the health consultation notes.

Behaviour, hearing, and speech and language each accounted for almost a quarter of the problems detected after the HKC (Box 2).

Child health concerns and the Healthy Kids Check

Twenty-six children had 39 problems identified and were either further managed (scheduled for monitoring or review) or referred to specialist services as a direct result of the HKC. Of these, 19 children (19/557, 3% of the total sample) had their problems confirmed, resulting in a change of management (Box 3) (Appendix 3). The most frequent confirmed problems involved speech and language (9/31), hearing (6/31), behaviour (3/31) and vision (3/31) (Box 3).

No further action was recorded for the problems of 49 children (9% of total sample). For these children, the most common problems detected involved toileting (20/56), speech and language (7/56) and behaviour (6/56). For 42 children (8% of total sample) with health-related concerns detected at the HKC, information about scheduled reviews, referral letters or referral outcomes was either missing or unclear (Box 3).

Discussion

The HKC is administered by GPs, who are well placed to identify and manage potential problems early. That 144 problems were detected in 116 children suggests that GPs are diligent in detecting child health concerns. In our medical records audit of two Queensland general practices, we documented a change in management for 3% (19/557) of children, no change for 1% (7/557), no further action for 9% (48/557) and unclear or missing data for a further 8% (42/557). We conservatively estimate that between 3% (19 children with confirmed problems) and 11% (19 children with confirmed problems and 42 children with unclear outcomes) of children have a change in clinical management resulting from the HKC (based on numbers where change was clear and unclear). Our lower estimate of 3% is similar to a developmental screening study that followed referral pathways of children to early intervention services.17

In our study, for 19 children, we identified 26 problems that resulted in clinically important changes to management. Assuming adequate services and interventions were available, accessed and effective, these children benefited from the HKC. They may also have experienced harms (eg, from overdiagnosis of problems that would never have had a negative impact18), but this cannot be determined from the available data.

A lack of independent toileting was the most detected and least actioned problem. This is appropriate: questioning about independent toileting is a mandatory component of the HKC, but action is not recommended until after 5 years of age because of evidence of ineffectiveness.11 However, discussing with parents what is “normal” and giving practical advice about toileting issues may still be beneficial. Child behaviour concerns can be managed actively or passively. A GP may encourage parents to try several strategies to ameliorate child behaviour problems (active), or consider the child’s behaviour to be probably normal and adopt a “test of time” or “watchful observation” approach (passive). There was often insufficient detail in the medical record to distinguish between active and passive approaches; we were therefore unable to determine whether the outcome was appropriate. Finally, problems detected after the HKC may represent missed or new incident problems (not present at the time of the HKC). For example, several learning problems are unlikely to be detected until a child is of school age. Reasons for our lack of allergy notation data are unclear: allergies may have been recorded elsewhere than in the consultation sections of the medical record; the GP may not have recorded any (perhaps not realising their mandatory reporting status); or there were none.

The study has several strengths. It is the first evaluation of HKC outcomes. We used medical records from two large general practices; two researchers independently extracted data; and all data were double entered as a reliability check (few discrepancies were found).

There were also limitations. First, the study design relied on accurate and detailed documentation of events in medical records. We could not determine the outcome of reviews or referrals for 42 children who had a health problem detected during the HKC. Therefore, our estimation of a positive predictive value of the HKC of 3% is likely to be an underestimation. Second, screening can be harmful as well as beneficial. We could not determine whether children (or their parents) experienced harms (such as anxiety regarding the screening results or overdiagnosis).18 Conversely, reassurance of “normal development” is often suggested as a screening benefit; however, medical record audits do not produce these data. Third, because this was a cross-sectional study, the time between the HKC and the medical record audit varied between subjects. Therefore, some data may be missing because of insufficient time between the HKC and rescheduled or specialist appointments. Some children may have had problems that were missed but insufficient time had elapsed for these problems to be recorded, or children may have moved to a new general practice. Finally, this study design precludes estimating the true negative value for the HKC (which would require an independent examination of every child to determine the false negatives). It is impossible to estimate false negatives without an intervention trial (in which all screened negative children would be subject to a gold-standard assessment).

Our data suggest that GPs are identifying important child health concerns during the HKC, using appropriate clinical judgement for the management of some conditions, and referring when concerned. It also appears that GPs use HKC screening to conduct opportunistic examinations that extend the parameters of the HKC, identifying other clinically meaningful child health concerns. However, they may be hampered by limited means of detection with little evidence of effectiveness. We also have no knowledge of the cost-effectiveness of the HKC, although given that its timing coincides with vaccination at 4 years of age, the incremental cost is likely small. Despite lack of evidence of effectiveness, the HKC is scheduled to be expanded to include social and emotional development and assessment at 3 years of age.

Longitudinal studies of community samples or birth cohorts report that few young children have high internalising (eg, anxiety, depression) and/or externalising behaviours (eg, oppositional behaviour) at any assessment period, and that very few continue these behaviours to school entry.19,20 An Australian prospective cohort study following children to adulthood reported screening children at 5 years of age for behavioural, social and emotional concerns poorly predicted psychopathology at 21 years of age.21 Estimates of the sensitivity and specificity of the age 5 years screening tool were 23% and 82%, respectively, for any diagnosis of psychopathology at 21 years of age. In other words, single screening for behavioural, social and emotional problems does not confer long-term benefits for most children, perhaps because of the rapid developmental changes.21 Given the significant child health concerns detected throughout the medical records and at various time points (including times other than the one-off HKC) in our study, we must consider the value of a single-point assessment, which has components of limited evidence.

Despite interventions to improve the uptake of screening in paediatric primary care, few studies have tracked developmental outcomes of those screened.7 Previous research in child developmental screening and subsequent intervention reported that screening for developmental delays was not effective in changing health outcomes for children, and that harms occurred for some parents.22 A longitudinal, prospective cohort study of children undertaking the HKC is needed to understand the long-term outcomes of children with identified health concerns, and to determine whether interventions help or harm.

1 Medical records audit — flow diagram

2 Number of children, and categories, numbers and proportions of problems detected before, during and after the Healthy Kids Check (HKC)

|

Problems detected*

|

Before HKC†

|

During HKC

|

After HKC‡

|

Total

|

|

|

No. of children

|

107

|

116

|

23

|

557

|

|

Mandatory HKC components

|

|

|

|

|

|

Height and weight

|

14 (8%)

|

4 (3%)

|

0

|

18 (5%)

|

|

Vision

|

8 (5%)

|

21 (15%)

|

1 (3%)

|

30 (9%)

|

|

Hearing

|

23 (13%)

|

21 (15%)

|

7 (24%)

|

51 (15%)

|

|

Oral health

|

0

|

10 (7%)

|

0

|

10 (3%)

|

|

Toileting

|

2 (1%)

|

22 (15%)

|

1 (3%)

|

25 (7%)

|

|

Other problems detected

|

|

|

|

|

|

Behaviour

|

10 (6%)

|

13 (9%)

|

7 (24%)

|

30 (9%)

|

|

Eating

|

3 (2%)

|

3 (2%)

|

0

|

6 (2%)

|

|

Anatomical

|

32 (18%)

|

8 (6%)

|

2 (7%)

|

42 (12%)

|

|

Cardiac

|

9 (5%)

|

5 (3%)

|

0

|

14 (4%)

|

|

Motor

|

8 (5%)

|

3 (2%)

|

2 (7%)

|

13 (4%)

|

|

Speech and language

|

41 (24%)

|

29 (20%)

|

7 (24%)

|

77 (22%)

|

|

Head circumference

|

6 (3%)

|

0

|

0

|

6 (2%)

|

|

Psychological disorders

|

10 (6%)

|

3 (2%)

|

0

|

13 (4%)

|

|

Other

|

8 (5%)

|

2 (1%)

|

2 (7%)

|

12 (3%)

|

|

Total no. of problems*

|

174

|

144

|

29

|

347

|

|

|

* Children could have more than one problem; 311 children did not experience any problem at any time. † Includes 28 children with problems identified before and during HKC. ‡ Does not include six children also identified with different problems before the HKC but with no problems at the HKC.

|

3 Changes in management resulting from problems detected in the Healthy Kids Check (HKC)

|

Problems detected*

|

Managed or referred and problem identified

|

Managed or referred and no problem identified

|

No action taken

|

Unclear or missing data

|

Total

|

|

|

No. of children

|

19

|

7

|

48

|

42

|

116

|

|

Mandatory HKC components

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Height and weight

|

1

|

0

|

2

|

1

|

4 (3%)

|

|

Vision

|

3

|

0

|

4

|

14

|

21 (15%)

|

|

Hearing

|

6

|

2

|

5

|

8

|

21 (15%)

|

|

Oral health

|

2

|

0

|

3

|

5

|

10 (7%)

|

|

Toileting

|

1

|

0

|

20

|

1

|

22 (15%)

|

|

Other problems detected

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Behaviour

|

3

|

1

|

6

|

3

|

13 (9%)

|

|

Eating

|

0

|

0

|

3

|

0

|

3 (2%)

|

|

Anatomical

|

1

|

1

|

3

|

3

|

8 (6%)

|

|

Cardiac

|

2

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

5 (3%)

|

|

Motor

|

1

|

0

|

1

|

1

|

3 (2%)

|

|

Speech and language

|

9

|

1

|

7

|

12

|

29 (20%)

|

|

Psychological disorders

|

2

|

1

|

0

|

0

|

3 (2%)

|

|

Other

|

0

|

0

|

1†

|

1‡

|

2 (1%)

|

|

Total no. of problems*

|

31

|

8

|

56

|

49

|

144

|

|

|

* Children could have more than one problem. † Dyslexia. ‡ Diabetes.

|

more_vert

more_vert