There is increasing global interest in the use of frequently indicated medications in fixed-dose combination for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD).1,2 Evidence of the effectiveness of such polypills as a strategy in improving adherence to recommended treatment and potentially lowering costs is growing.3,4 Although there are combination blood pressure-lowering and cholesterol-lowering medications, a more comprehensive cardiovascular polypill (containing generic aspirin, a lipid-lowering and two blood pressure-lowering agents) is not currently available in Australia. At a feasible cost of less than $1 per day5 compared with a minimum cost in Australia of $1.70 per day for individual generic therapies (http://pbs.gov.au/info/about-the-pbs), prima facie evidence exists for extensive savings from such a strategy in Australia.

The cost-effectiveness of polypill-based strategies compared with individual medications has yet to be tested in real-life settings, although cost-effectiveness has been shown in different patient groups and health care settings using modelled projections.5,6–8 For instance, based on a modelled analysis of high-risk primary care Dutch participants, polypill use after opportunistic screening was cost-effective among people aged over 40 years.8 Similarly, a polypill strategy was found to be cost-effective and potentially cost-saving in older patients after myocardial infarction.7

This analysis is based on the Kanyini Guidelines Adherence with the Polypill (GAP) pragmatic randomised controlled clinical trial and linked health service and medication administrative claims data from Medicare Australia. Kanyini GAP was pragmatic in that it was conducted within the primary care setting, with the study drug dispensed through community pharmacies, to test the effectiveness of a polypill-based strategy in real-world practice.9 In the trial, the polypill improved patients’ adherence to treatment and there was no difference in mean blood pressure and cholesterol levels.3 The results were consistent with a larger sister trial, the UMPIRE (Use of a Multidrug Pill in Reducing Cardiovascular Events) study. Conducted in Europe and India, UMPIRE found that a polypill strategy yielded improvements in self-reported adherence, along with statistically significant but small additional reductions in blood pressure and cholesterol, compared with non-polypill treatment, in the polypill arm.4 A unique design feature of Kanyini GAP was that all medications, including the polypill, were dispensed at an out-of-pocket charge consistent with prevailing Medicare subsidies (around $35 per medication per month for general patients).

Methods

A within-trial cost analysis of the polypill strategy versus usual care was conducted from the Australian health system perspective (ie, government plus patient costs). Kanyini GAP was carried out within Indigenous and non-Indigenous urban, rural, and remote primary care settings across Australia (randomisation from January 2010 to May 2012; median follow-up, 19 months; maximum follow-up, 36 months).3

Data on health service and medication expenditure throughout Kanyini GAP were obtained via individually linked Australian Medicare records for study participants who consented to linkage. Two separate Medicare datasets were analysed: the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS), which records government and patient costs of general practitioner and specialist visits and diagnostic tests; and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), which records the total government and patient costs of all medications dispensed outside hospital. The PBS data do not include polypill costs, as it is not marketed in Australia. As no difference was found in safety or clinical outcomes between treatment groups in the Kanyini GAP trial, we assumed no differences in hospital-related expenditure.

The primary outcome was mean MBS and PBS expenditure per patient per year. The base year for the analysis was 2012.10 This study was approved by human research ethics committees in all relevant jurisdictions (Sydney South West Area Health Service; Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of New South Wales; Cairns Base Hospital; Princess Alexandra Hospital Centres for Health Research; Central Australia; Northern Territory Department of Health and Menzies School of Health Research; Monash University). Each participant provided written informed consent.

Statistical analysis

Multivariable analysis was conducted to accommodate potential differences between treatment groups, given these analyses were restricted to the subset of trial participants consenting to Medicare linkage.11 Non-significant demographic, socioeconomic, health and treatment-related covariates (P > 0.10) were removed via backwards stepwise elimination. To account for the empirical distribution of MBS and PBS cost data,11–14 generalised linear models were used to estimate the primary outcome, and the marginal difference between treatment groups was compared (Wald test). Deb–Manning–Norton programs for Stata 12.1 (StataCorp) were used.12

Results

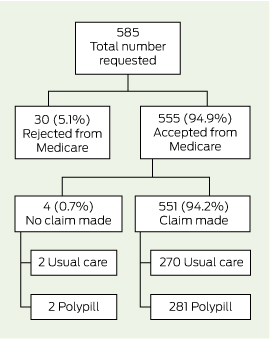

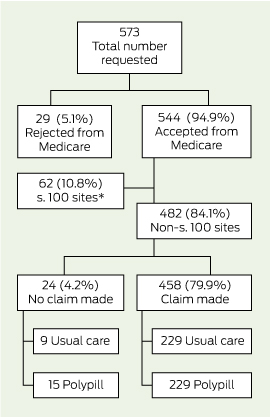

Box 1 and Box 2 detail the flow of patients through this analysis. Consent for linkage with MBS and PBS data was obtained from 93.9% (585/623) and 92.0% (573/623) of trial participants, respectively, and data were provided for 94.9% of participants (MBS, 555/585; PBS, 544/573). With regard to PBS data, 10.8% (62/573) of consenting participants were receiving medications under the special rural and remote access provisions of section 100 of the National Health Act 1953 (Cwlth) and were removed from this analysis, as these data were not captured by Medicare at an individual patient level (Box 2). There was no differential availability of linked data between treatment groups.

The MBS and PBS expenditures by the Australian health system (government plus patient costs) per patient per year, excluding the cost of the polypill, are presented in Box 3. The adjusted analysis predicted a mean cost saving for pharmaceutical expenditure of $989 (95% CI, $648–$1331) per patient per year (P < 0.001) to the health system. No significant differences were found in MBS expenditure.

Discussion

Our study showed that participants receiving polypill-based care had significantly lower pharmaceutical expenditure than usual care, with no difference in health service expenditure. The overall potential savings are dependent on the reimbursement price of the polypill. Under current Australian guidelines, fixed-dose combinations such as the polypill are reimbursed at no greater than the sum of the costs of the generic components,15 which was $1.70 per day at the time the trial was conducted. At this maximum price, and based on an average of 264 days per year on polypill treatment as observed in the treatment arm of the Kanyini GAP study,3 the annual savings to the health system would be $540 (ie, $989 − $1.70 × 264 days) per patient.

The Kanyini GAP trial found that the polypill was safe and effective in improving combination preventive treatment use by patients.3,4 Using primary care expenditure data, our within-trial analysis provides evidence of significant cost savings through the introduction of a CVD polypill, showing its economic dominance over conventional individual therapies. The ACE Prevention project, an Australian economic modelling study,5 also indicated dominance, estimating that a polypill at $200 per person per year was cost saving and resulted in a large population health impact, even when provided to patients at lower risk than those in the Kanyini GAP trial. If we had applied this lower cost in our analysis, we would have estimated annual health system savings of $789 per patient.

Challenges remain before large cost savings can be realised in Australia. First, no polypill has had regulatory approval in Australia to date. While several cardiovascular combinations have been approved, these are simple two-component combinations approved on the basis of straight substitution among patients receiving recommended medications (among whom the benefits are smallest),3,4 and have probably increased costs as a result of not being subject to automatic price reductions.16 Another challenge will be appropriate scale-up while maintaining overall cost savings — large investments will be required in order to bring about practice change for this relatively new way of treating patients.

One limitation with using PBS data is that over-the-counter and very low-cost medications priced at below the government copayment level are not captured. However, this potentially leads to an underestimate of the cost savings as it is likely to include some of the individual cardiovascular medicines in usual care, such as aspirin. Additionally, subsequent reductions in the cost of usual care associated with the expiry of patents for atorvastatin and rosuvastatin since conducting the Kanyini GAP trial may have an impact on the translation of such cost savings into contemporary practice.

This is the first study using individual patient-linked administrative data to evaluate the cost offsets associated with a CVD polypill compared with current practice. Given that over 600 000 Australians at high risk of CVD are currently prescribed antiplatelet, blood pressure and lipid-lowering medication, and a similar number are on partial treatment,17,18 this polypill has the potential to not only help to reduce the large gaps that exist in Australia between recommended and actual treatment for patients with CVD,18 but also to free up considerable amounts of pharmaceutical expenditure.

2 Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme expenditure

* Patients receiving medications under the special rural and remote access provisions; individual-level data not captured by Medicare.

3 Health system expenditure (government plus patient costs) per patient per year of follow-up*

|

Scheme |

Usual care |

Polypill |

Marginal difference |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Medicare Benefits Schedule |

|||||||||||||||

|

No. of participants |

270 |

281 |

– |

||||||||||||

|

Unadjusted expenditure, mean (95% CI) |

$1772 ($1581 to $1963) |

$1760 ($1602 to $1917) |

$13 (− $236 to $261)† |

||||||||||||

|

Adjusted‡ expenditure, mean (95% CI) |

$1767 ($1583 to $1951) |

$1770 ($1615 to $1926) |

$40 (− $202 to $281) |

||||||||||||

|

Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme |

|||||||||||||||

|

No. of participants |

229 |

229 |

– |

||||||||||||

|

Unadjusted expenditure, mean (95% CI) |

$2438 ($2100 to $2775) |

$1443 ($1285 to $1601) |

$995 ($622 to $1368)†¶ |

||||||||||||

|

Adjusted§ expenditure, mean (95% CI) |

$2448 ($2141 to $2754) |

$1446 ($1291 to $1602) |

$989 ($648 to $1331)†¶ |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* 2012 A$, estimated with generalised linear model (gamma family, log link). † In favour of polypill. ‡ Adjusted for sex, Australian rural and remote area index (http://www.aihw.gov.au/rural-health-rrma-classification), adherence at baseline, history of cardiovascular disease and prior medication use. § Adjusted for sex, Australian rural and remote area index, health care concession status–income interaction, adherence at baseline, history of cardiovascular disease and prior medication use. ¶ P < 0.001. |

|||||||||||||||

more_vert

more_vert