Acute respiratory tract infections (RTIs) are managed at more than 6 million general practice visits each year in Australia.1 RTIs such as the common cold (acute upper respiratory tract infection [URTI]), acute bronchitis/bronchiolitis, acute tonsillitis and pneumonia create a severe health and economic burden.1 They are most prevalent among young children, especially when they attend preschools or day care centres. It is estimated that children younger than 5 years have a cold 23% of the time,2 with 70% of the costs attributed to carers’ lost time at work.3

Current guidelines on the treatment and management of RTIs in children include supportive management such as hydration and rest.4 Over-the-counter (OTC) medications such as analgesics and cough medications may reduce the severity of symptoms, but they do not cure or prevent the illness.

As most RTIs are caused by viruses, antibiotics have limited therapeutic value and should only be prescribed if an RTI is suspected to be bacterial in origin. However, overseas studies suggest high rates of antibiotic prescribing for RTIs among young children.5,6 Contributing factors include physicians’ diagnostic uncertainty, parents’ expectation of receiving antibiotics and physicians’ perception of parents’ satisfaction with the visit.7,8

The current management of RTIs among children in Australia, especially in general practice, is unclear. Much of the published data about the management of this cohort originated from the United Kingdom,9 Canada,5 and the United States.10,11 Therefore, we aimed to explore the current management of RTIs in children under the age of 5 years in Australian general practice using data from the Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health (BEACH) program.

Methods

We analysed BEACH data collected from April 2007 to March 2012 inclusive. BEACH methods are described elsewhere in detail;12 however, in summary, BEACH is a continuous, paper-based, national study of general practitioner activity in Australia. Every year, as part of a rolling random sample of 1000 GPs, each GP provides information on 100 consecutive GP–patient encounters with consenting, unidentified patients. BEACH collects GP characteristics and, for each encounter: patient characteristics, reasons for encounter, number of problems managed and clinical actions initiated.13,14 Clinical actions may include medication, referral, pathology testing, and non-pharmacological treatment (eg, counselling, giving advice, education or minor surgery). The BEACH program is approved by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee.

BEACH study statistical analyses in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute) are adjusted for clustering of encounters around each GP. Statistically significant differences are determined by non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals, equivalent to P < 0.006.

For this study, we identified all GP encounters with patients younger than 5 years (60 months) at the date of encounter. We analysed those encounters where at least one of the following four RTIs (by International Classification of Primary Care, second edition [ICPC-2] code) was recorded as problem managed:

- upper respiratory infection, acute (“URTI”) [R74];

- bronchitis/bronchiolitis, acute (“bronchitis”) [R78];

- tonsillitis, acute (“tonsillitis”) [R76]; and

- pneumonia [R81].

These RTIs were selected on the basis of their frequency and importance in general practice paediatric management.

The management rate of each of these four RTIs per 100 paediatric encounters was compared in terms of: season (summer [December–February] v winter [June–August]); GP sex; and GP age group (≥ 55 years v < 55 years).

We further examined the use and rate (per 100 of each specified RTI) of six management (“clinical action”) options:

- antibiotic medications;

- prescribed or supplied non-antibiotic medications;

- medications advised for OTC purchase;

- referrals (to specialists and/or allied health professionals);

- pathology testing; and

- counselling (including advice/education) at the encounter.

Results

From April 2007 to March 2012, there were 31 295 encounters (involving 4522 GPs) with children younger than 5 years. Of these children, 53.4% were boys, and 31.1% were aged under 1 year. One or more respiratory infections (ICPC-2 codes R71–R83) were managed at 9261 encounters — 29.6% (95% CI, 28.9%–30.3%) of these GP paediatric encounters.

Of these encounters, at least one of URTI, bronchitis or tonsillitis was recorded at 86.0% (results not shown), and at least one of URTI, bronchitis, tonsillitis or pneumonia was recorded at 88.1%. One or more of these four specified RTIs were managed at 8157 encounters, equating to 26.1% (95% CI, 25.4%–26.7%) of all GP paediatric encounters.

Box 1 presents patient demographics of all paediatric encounters and of those involving at least one of these four specified RTIs. For encounters where at least one of the four specified RTIs was recorded, there was a smaller proportion of patients in the < 1 year and a greater proportion in the 1 to < 4 years age groups and fewer patients new to the practice compared with all paediatric encounters. The characteristics of the two groups were otherwise similar.

The management rate (per 100 paediatric encounters) of each of the four specified RTIs (and the combined total) is shown in Box 2. For all four specified RTIs combined, the management rate was higher among older GPs (≥ 55 years) than among younger, higher among male GPs than female, and higher in winter than summer. URTI was the most frequently managed respiratory infection (18.6), followed by bronchitis (4.2), tonsillitis (2.7) and pneumonia (0.6). The problem management rates of URTI, bronchitis and pneumonia were significantly higher in winter than in summer.

The management rate of URTI and bronchitis was significantly higher among male GPs than among female GPs (Box 2). The rate of tonsillitis management was higher among older GPs than younger GPs (Box 2). There was no significant seasonal difference in the rate at which each management option (“clinical action”) was recorded for each of the specified RTI problems (results not shown).

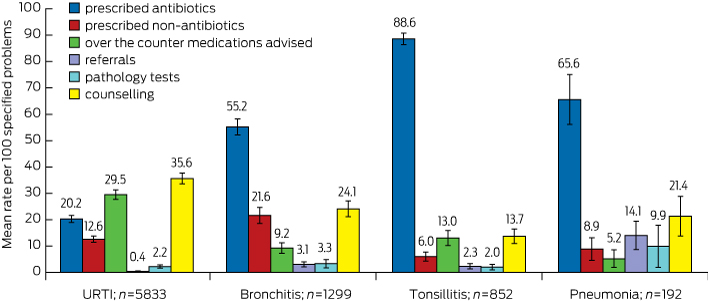

Box 3 illustrates the mean rate of management options recorded per 100 of each of the four specified RTI problems. The antibiotic prescribing rate for the management of tonsillitis (88.6), was statistically significantly higher than that for pneumonia (65.6), bronchitis (55.2) and URTI (20.2). URTI had the highest rate of OTC medications advised (29.5), compared with tonsillitis (13.0), bronchitis (9.2) and pneumonia (5.2). URTI also had the highest rate of counselling/advice/education (35.6), compared with bronchitis (24.1), pneumonia (21.4) and tonsillitis (13.7). The highest rate of prescribing non-antibiotic medications was for bronchitis (21.6). The highest rate of referrals given (14.1) and pathology tests ordered (9.9) were for pneumonia.

The rate of antibiotic prescribing per 100 URTI problems was higher among male GPs (22.5; 95% CI, 20.6–24.3) than female GPs (17.2; 95% CI, 15.3–19.1) and similarly for prescribed non-antibiotic medication per 100 URTI problems (14.0; 95% CI, 12.3–15.7 v 10.7; 95% CI, 9.1–12.3). The rate of pathology tests ordered per 100 tonsillitis problems was significantly higher among female GPs than among male GPs (3.9; 95% CI, 1.6–6.3 v 0.6 95% CI, 0.0–1.3). The rate of counselling/advice/education per 100 bronchitis problems was significantly higher among female GPs than among male GPs (31.2; 95% CI, 25.9–36.5 v 19.1; 95% CI, 15.7–22.5). No other significant differences were found on this GP sex comparison analysis.

The rate of antibiotic prescribing per 100 URTI problems was significantly higher among older GPs (≥ 55 years) than younger GPs (25.4; 95% CI, 22.8–28.0 v 18.0; 95% CI, 16.4–19.5). The rate of counselling/advice/education per 100 URTI problems was significantly higher among younger GPs than older GPs (38.1; 95% CI, 35.5–40.6 v 30.2; 95% CI, 26.4–33.9). The rate of advising OTC medications per 100 tonsillitis problems was significantly higher among younger GPs than among older GPs (16.2; 95% CI, 12.3–20.0 v 8.0; 95% CI, 4.1–12.0). No other significant differences were found on this GP age group comparison analysis.

Discussion

Our study provided insight into the current management of selected respiratory infections in children younger than 5 years by GPs in Australia.

Our study found that URTI was the most common RTI managed by GPs in this age group. This finding is similar to those reported from Australia, Malaysia and the UK.1,15,16 Studies have shown that parental decisions to consult for a young child with the common cold are influenced by the age of the child, type of symptoms, parents’ education level and their perception of the severity of the symptoms.17 Whereas 60% of parents would visit a GP if their child had a cold,11 parents from a lower income group were 1.5 times more likely to seek advice from health services.18

Despite our analyses showing URTI having the lowest antibiotic prescription rate of the four specified RTIs, guidelines suggest this is beyond clinical requirement. Nonetheless, this result compared favourably with overseas studies,6,19,20 where the reported antibiotic prescription rate for URTI was as high as 42%.6 Similarly, those studies reported the antibiotic prescription rate for bronchitis to be as high as 86%.6,19

Several studies have suggested reasons why antibiotics might be prescribed unnecessarily for (non-bacterial) RTIs.7,15,18,19,21 These include diagnostic uncertainty in children,7 possibly poor medical knowledge of respiratory infections,21 physicians’ perception of parental satisfaction,8 and parents’ misconceptions and expectations regarding the treatment of RTIs, especially the perceived benefits of antibiotics.7,10,11,18 Some of these studies have recommended education about RTIs and antibiotics for parents and carers,10,15 and for physicians to aid decision making and optimal management.22

While URTIs had the lowest antibiotic prescription rate of the four RTIs in our study, they have the highest rate of OTC medications advised. Although physicians, researchers and paediatricians agree that common cold treatments and remedies do not reduce illness duration and offer little benefit,23 GPs might still advise OTC medications (rather than prescribe antibiotics) to address some parents’ expectations that medication will cure the common cold.

For each of the four RTIs, we found that the rate of pathology tests ordered was lower than the rate of antibiotic prescribing. Possible reasons for this include the technical difficulty of pathogen identification in RTIs; the invasive nature of throat swabs in young children; the cost; and the likelihood that management would not be altered by the microbiological results, which are often delayed.22,24,25

There were differences in the management of paediatric RTIs by GP age and sex; male GPs prescribed medication (antibiotics and non-antibiotics) for URTI significantly more frequently than female GPs, and were less likely to provide counselling and education for bronchitis than female GPs. Older GPs prescribed antibiotics for URTI more frequently, but were less likely to provide counselling/advice/education for URTI than younger GPs.

In our study, antibiotic prescribing rates for URTI, bronchitis and tonsillitis were higher than recommended by the current Therapeutic guidelines.4 However, our study was limited by a lack of data on patient comorbidities, which could have influenced GPs’ diagnostic and management decisions. Similarly, the practice of “wait and see” before filling antibiotic prescriptions or buying OTC medications was not recorded, leading to possible overreporting of prescribed and OTC medications.

Nevertheless, the rigour of BEACH data has been well established, and this study gives a detailed estimate of the frequency of and management options for specified paediatric RTIs. Our results open several promising avenues for further research into parents’ and health professionals’ attitudes and practices regarding antibiotic prescribing and OTC medications for managing RTIs in young children. Better understanding of these factors will help maintain favourable management practices.

1 Demographics of general practice patients younger than 5 years, overall and with respiratory infections, 2007–2012

|

All patients (n = 31 295) |

Patients with at least one of the four specified respiratory tract infections* (n = 8157) |

||||||||||||||

|

Demographics |

No. |

% (95% CI) |

No. |

% (95% CI) |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Sex |

|||||||||||||||

|

Male |

16 548 |

53.4% (52.7%–54.0%) |

4319 |

53.3% (52.2%–54.4%) |

|||||||||||

|

Female |

14 468 |

46.6% (46.0%–47.3%) |

3782 |

46.7% (45.6%–47.8%) |

|||||||||||

|

Missing data† |

279 |

56 |

|||||||||||||

|

Age group in years |

|||||||||||||||

|

< 1 |

9730 |

31.1% (30.4%–31.8%) |

2056 |

25.2% (24.2%–26.2%) |

|||||||||||

|

1 to < 2 |

8053 |

25.7% (25.2%–26.3%) |

2233 |

27.4% (26.4%–28.4%) |

|||||||||||

|

2 to < 3 |

4917 |

15.7% (15.3%–16.2%) |

1559 |

19.1% (18.2%–20.0%) |

|||||||||||

|

3 to < 4 |

4240 |

13.5% (13.1%–14.0%) |

1251 |

15.3% (14.5%–16.1%) |

|||||||||||

|

4 to < 5 |

4355 |

13.9% (13.5%–14.3%) |

1058 |

13.0% (12.2%–13.7%) |

|||||||||||

|

Missing data† |

0 |

0 |

|||||||||||||

|

Indigenous status |

|||||||||||||||

|

Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander |

699 |

2.5% (2.1%–2.9%) |

160 |

2.2% (1.7%–2.7%) |

|||||||||||

|

Non-Indigenous |

27 153 |

97.5% (97.1%–97.9%) |

7121 |

97.8% (97.3%–98.3%) |

|||||||||||

|

Missing data† |

3443 |

876 |

|||||||||||||

|

HCC status |

|||||||||||||||

|

HCC |

7380 |

25.9% (24.8%–27.0%) |

2042 |

27.4% (25.9%–28.9%) |

|||||||||||

|

No HCC |

21 116 |

74.1% (73.0%–75.2%) |

5416 |

72.6% (71.1%–74.1%) |

|||||||||||

|

Missing data† |

2799 |

699 |

|||||||||||||

|

Practice status |

|||||||||||||||

|

New to practice |

4754 |

15.4% (14.7%–16.0%) |

1051 |

13.0% (12.1%–14.0%) |

|||||||||||

|

Seen previously |

26 199 |

84.6% (84.0%–85.3%) |

7012 |

87.0% (86.0%–87.9%) |

|||||||||||

|

Missing data† |

342 |

94 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

HCC = Health Care Card. * Acute upper respiratory tract infection, acute bronchitis/bronchiolitis, acute tonsillitis and pneumonia. † Missing data were removed from calculations. |

|||||||||||||||

2 Respiratory problems among children younger than 5 years per 100 encounters, by general practitioner age and sex, and by season, for the four specified respiratory tract infections, 2007–2012

|

No. of encounters with patients < 5 years |

Problems managed per 100 encounters (95% CI) |

||||||||||||||

|

URTI |

Bronchitis |

Tonsillitis |

Pneumonia |

Total |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Total |

31 295 |

18.64 (18.05–19.23) |

4.15 (3.89–4.42) |

2.72 (2.51–2.93) |

0.61 (0.51–0.71) |

26.13 (25.48–26.78) |

|||||||||

|

GP age group in years* |

|||||||||||||||

|

< 55 |

21 947 |

18.51 (17.82–19.20) |

3.96 (3.65–4.27) |

2.42 (2.19–2.66) |

0.61 (0.49–0.73) |

25.51 (24.76–26.25) |

|||||||||

|

≥ 55 |

9195 |

18.99 (17.84–20.14) |

4.64 (4.12–5.17) |

3.39 (2.96–3.83) |

0.62 (0.43–0.81) |

27.65 (26.34–28.96) |

|||||||||

|

GP sex |

|||||||||||||||

|

Female |

14 410 |

16.99 (16.18–17.80) |

3.71 (3.34–4.09) |

2.46 (2.17–2.76) |

0.73 (0.56–0.90) |

23.89 (22.97–24.81) |

|||||||||

|

Male |

16 885 |

20.05 (19.20–20.90) |

4.52 (4.16–4.89) |

2.94 (2.65–3.24) |

0.52 (0.40–0.63) |

28.03 (27.12–28.94) |

|||||||||

|

Season of consultation |

|||||||||||||||

|

Summer |

6571 |

14.35 (13.22–15.48) |

2.48 (2.08–2.88) |

2.71 (2.24–3.18) |

0.41 (0.23–0.59) |

19.95 (18.71–21.19) |

|||||||||

|

Winter |

8636 |

21.86 (20.60–23.12) |

5.33 (4.72–5.93) |

2.84 (2.43–3.25) |

0.88 (0.65–1.11) |

30.91 (29.47–32.34) |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

URTI = upper respiratory tract infection. Summer = December–February. Winter = June–August. * Age was missing for 153 GPs; their data were removed from calculations. |

|||||||||||||||

more_vert

more_vert