Indigenous health expenditure trends are obscured amid myriad medical indicators and reports on Indigenous Australians’ health. The Australian Government’s Closing the Gap strategy seeks health equality for Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander peoples. However, neglecting the economics of the strategy perpetuates poor system performance as financial and resource constraints on individuals, and increasingly on the public health system, are ignored.

In contrast with Australian reporting, nearly a third of health system performance indicators of the World Health Organization’s 100 core health indicators (2015) relate to expenditure.1

Four interacting factors within Australia’s health system are potentially lethal for many Indigenous people:

-

Limited Indigenous-specific primary health care services;

-

Indigenous peoples’ underutilisation of many mainstream health services and limited access to government health subsidies;

-

Increasing price signals in the public health system and low Indigenous private health insurance rates;

-

Failure to maintain real expenditure levels over time.

Government expenditure is not commensurate with the substantially greater and more complex health needs of Indigenous Australians. It should be indexed to reflect these needs. While the average health expenditure per person for Indigenous Australians is 1.47 times that for non-Indigenous people, differences in indicators such as mortality and prevalence of disease are much greater.2–4 An expenditure index of (at least) two may appropriately reflect greater health needs.2–4

The “four A barriers” to Indigenous peoples’ access to mainstream primary health services — availability, affordability, (cultural) acceptability and appropriateness (to health need) — persist in all jurisdictions and geographical areas.2–4

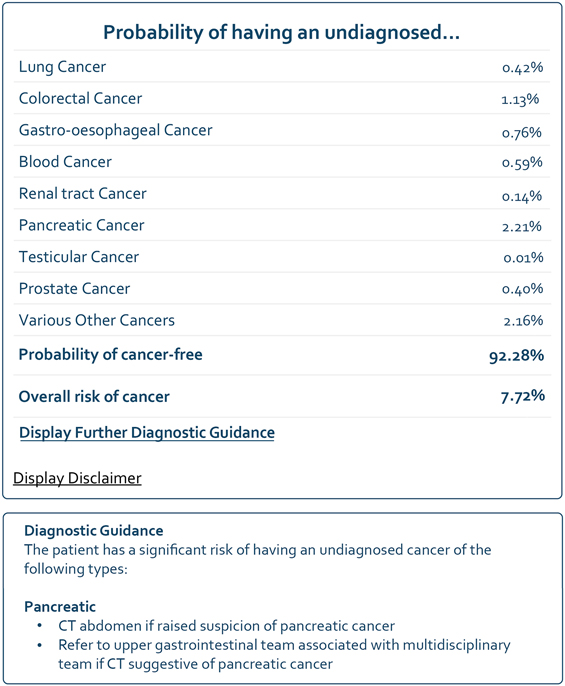

Access to health services is recognised as critical to closing the gap.2,3 Not recognised are substantial fiscal losses from the Indigenous health sector arising from limited access to mainstream services. Ratios of Australian Government Indigenous and non-Indigenous health expenditure per person on major mainstream services are represented in the Box, with estimates of resulting fiscal losses from the Indigenous health sector.

Some major federal government health program expenditures are biased towards non-Indigenous people at the expense of other components of the health budget. For example, private health insurance accounts for nearly 10% of all federal government health expenditure: 55% of the population benefits from this, but at least 83% of Indigenous Australians do not.5

Increasing use of price signals, including copayments in the public health system and the Medicare Benefits Schedule price freeze (“copayments by stealth”), will further aggravate access barriers.2,3

Moreover, the government has failed to maintain Indigenous (real) health expenditures over time in line with population growth, distribution and greater health needs. Australian government health expenditure is expected to increase by 8% over the two years to 2015–16. The Indigenous proportion will fall by 2%, a cut of $88 million in real terms. As a result, the proportion of the health budget allocated to Indigenous health will shrink, from 1.18% in 2013–14 to 1.07% in 2015–16.2,5–7 Planned substantial reductions in federal government health payments to the states and territories may aggravate these losses.

There appears to be an increasing disconnect between government commitments to Closing the Gap and expenditure allocations. Solutions include aligning Indigenous health policy with commensurate funding, weighting expenditure to reflect greater health need, and redirecting more expenditure to Aboriginal community-controlled health services.2

Box –

Underutilisation of mainstream services and government health subsidies3–5

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Ratios of Indigenous to non-Indigenous expenditure |

|||||||||||||||

|

Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) |

0.67 : 1 |

||||||||||||||

|

Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) |

0.80 : 1 |

||||||||||||||

|

Private health insurance |

0.15 : 1 |

||||||||||||||

|

Resulting annual fiscal losses from Indigenous health (2014 estimates) |

|||||||||||||||

|

MBS |

$192 million |

||||||||||||||

|

PBS |

$58 million |

||||||||||||||

|

Private health insurance |

$138 million |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

more_vert

more_vert