The known The availability of effective and acceptable contraception is critical to the realisation of sexual health, with an increasing shift toward promoting long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) methods at an international level.

The new LARC methods were used more frequently by contraception users in three Western Desert communities in Western Australia than at the national level. Continuation rates for etonogestrel implants compared well with those reported for other populations in Australia and internationally.

The implications Service delivery models incorporating community engagement and health promotion can be used to achieve high uptake and acceptability of LARC methods.

The right to decide the number and timing of pregnancies is recognised as critical to the realisation of sexual health.1 This is optimally achieved by making acceptable and effective contraception available, reducing the rates of unintended pregnancy. Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) are recommended as the first line approach because of their superior effectiveness, the limited contraindications, high user satisfaction, and suitability across the reproductive life cycle.2

In Australia, as in other developed countries, high rates of unintended pregnancy persist in association with high rates of use of contraception methods that require daily user compliance.3 In the 2007–2011 Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health (BEACH) study, the combined oral contraceptive pill was the most common contraceptive managed in Australian general practice consultations (68.6% of contraception-related encounters).4 The uptake of LARCs in Australia has been lower than in European countries (7% v 10–32% of contraception users)5 despite the international consensus favouring their adoption.2,6,7

The limited data available suggest a very different profile of contraceptive use in remote Aboriginal communities. The 2008 Central Australian STI (Sexually Transmissible Infection) Risk Factor study reported that 54% of 137 Aboriginal women used contraception (self-report by participants recruited while presenting to the local clinic); the most common contraceptive used was a LARC (74% used etonogestrel implants, 16.2% medroxyprogesterone depot).8 This is also consistent with the understanding of contraception by Indigenous women reported by a recent northern Australian remote Aboriginal community ethnographic study.9

Although frequently overshadowed by the focus on STIs, access to contraception is vital to sexual health, and is as important in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities as in any other Australian community. Assertions about the reasons for contraceptive choice in Aboriginal communities have recently been prominent in the media discussions of possible community closures.10 In view of the lack of published data, this study aimed to document the patterns of use, efficacy and acceptability of contraception in three remote Western Australian Aboriginal communities.

Methods

Our study had a mixed method design, using medical record data to describe patterns of contraception use, and semi-structured interviews to assess user attitudes and acceptance. The participants were Aboriginal women of reproductive age from three very remote communities in the WA Western Desert region with a combined population of 915 at the 2011 census.11 The two smaller communities are located within 90 minutes’ drive of the larger community. General practitioners employed by the Kimberley Aboriginal Medical Services (KAMS) live in the largest community, and provide medical services to all three. A remote area nurse (author DF), employed as a sexual health coordinator for all three communities since January 2013, resided and delivered services in these communities on a continuous basis. Information on services delivered during the audit period was compiled from reports produced to meet program funding requirements and from research notes (Box 1).12,13

Contraception use

An electronic medical record system (MMEx; ISA Technologies) has been used and shared by the three communities since November 2010. Some patients had also shared records with other Kimberley Aboriginal community-controlled health services. Prescriptions and consultation and medical history records, which included patient self-reports of contraceptives prescribed elsewhere, were searched for the keywords “contraception”, “implan*”, “depo*”, “tubal”, “hysterectomy”, “Mirena” and “intra-uterine” to identify contraceptive use during the audit period of 1 November 2010 – 1 September 2014. Billing records were searched for item numbers corresponding to contraceptive implant insertion or removal. A patient met the inclusion criteria if she was aged 12–50 years on 1 September 2014, was a regular patient (ie, one of the three clinics was recorded in MMEx as their primary health care provider and they had at least three recorded clinic attendances), and was recorded as being an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander.

An episode of use was defined as commencing with the time of initiation and lasting until the medication was ceased or removed, or the patient was lost to follow-up (documented as having moved from the communities, or after unsuccessful clinic recall attempts). Medroxyprogesterone episodes were classified as lapsed if the next dose was not given by 16 weeks, as per World Health Organization guidelines.14 Insertion dates for etonogestrel implants were recorded, if known, to the nearest month; alternatively, the earliest and latest dates an implant was known to be in situ were used to calculate the episode duration. Cases for which there were insufficient data to estimate duration of use were excluded from the survival analysis. An implant in situ beyond 3 years was considered to be still continuous.

Statistical analysis

Data extracted from MMEx were transferred into Excel 2010 (Microsoft) for initial data cleaning, and then imported into Stata 13 (StataCorp). One, 2- and 3-year etonogestrel implant and medroxyprogesterone injection continuation rates were evaluated with Kaplan–Meier survival analyses. Patients were censored for loss to follow-up and the removal of implants.

Acceptability of types of contraception

Proposed interview questions were discussed with groups of Aboriginal women at local yarning sessions before deciding the final list. Aboriginal women aged 16 years or more were then invited to participate in semi-structured interviews when presenting to any of the three clinics, and at community yarning events between 3 November 2014 and 13 January 2015. Responses and direct quotes were written down by the main investigator during the interview, then promptly transcribed into Word 2010 (Microsoft) documents. Questions focused on pregnancy planning and experiences, and the acceptability of different contraception options.

The individual documents were integrated into a textual database with the tabular functions of Word 2010. The research team then reviewed and conducted thematic analyses of the data. The initial focus was to explore the women’s personal experiences with contraception, and attitudes and beliefs about available options, with segments of text coded appropriately. The research team included an experienced Kimberley Aboriginal sexual health coordinator. The content of the coding categories was reviewed, and important and recurring themes identified. Conclusions were developed and triangulated with data from the database and quantitative data; rates of use and continuation (as markers of acceptability) were compared with narrative data about the women’s personal experiences.

Ethics approval and consultation

Aboriginal women elders from the communities were initially consulted to ensure that the project was consistent with local priorities. Women’s yarning sessions were then held in each community to inform local women about the project. This project received ethics approval from the Western Australian Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee Human Research Ethics Committee (reference, 585) and was supported by the Kimberley Aboriginal Health Planning Forum Research Subcommittee.

Results

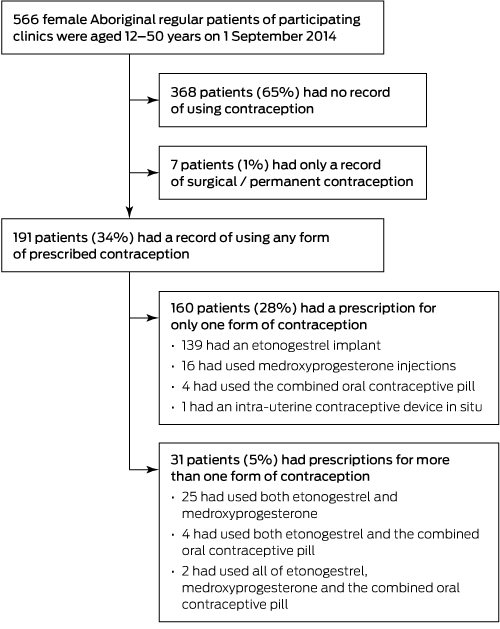

Five hundred and sixty-six women met the inclusion criteria, for 191 of whom (34%) a prescribed contraception method during the study period was recorded (Box 2). The etonogestrel implant was the most common contraceptive used; at the census date, 93 of 121 (77%) women with currently prescribed contraception were using the implant (Box 3), and a further ten had been lost to follow-up with an implant in situ. Medroxyprogesterone was the second most frequently prescribed contraceptive, but was used by only 9 of 121 women (7%) at the census date. Emergency contraception was only prescribed twice. Service providers in the communities reported that terminations of pregnancy were rare. Only 15% of women under 15 years of age had contraception prescriptions on record, rising to 55% for those aged 15–19 years.

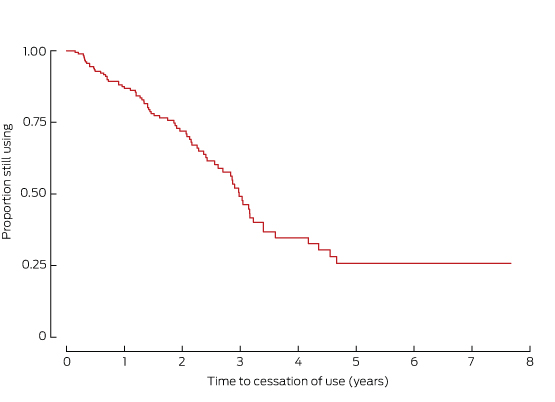

Two hundred episodes of etonogestrel implant use were recorded for 170 of the 566 women (30%), for a total of 373 patient-years. The median age at commencement was 20 years (interquartile range [IQR], 15–25 years). Most episodes (124 of 200, 62%) involved women under 25 years of age. The rate of continuation of use after one year was 87% (95% CI, 81–92%), after 2 years it was 72% (95% CI, 64–78%), and after 3 years it was 51% (95% CI, 41–60%) (Box 4). For 80 of 183 episodes (44%) for which prior parity was recorded, the woman was nulliparous at the time of insertion. For 67 of 200 episodes (34%), implants were inserted during the post partum period. The longest time in situ for a single implant was 4.4 years. No woman became pregnant with an implant in situ.

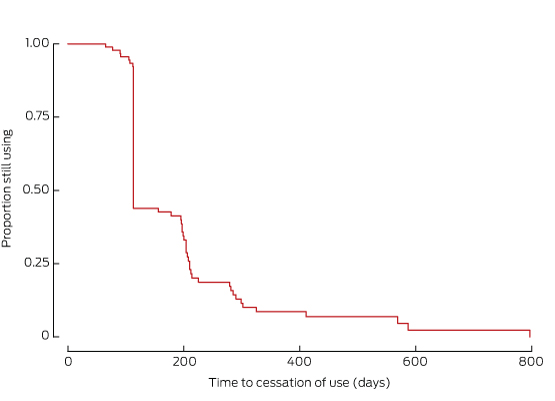

Forty-three women (8%) received 162 doses of medroxyprogesterone in 94 episodes of contraceptive use. The median age at the first dose was 24 years (IQR, 17–37 years); the median number of doses per episode of continuous use was one (range, 1–8). In 29 of 71 episodes for which prior parity was known, the woman was nulliparous at the time of the first dose. Eleven of 43 medroxyprogesterone users subsequently became pregnant, all at least 26.5 weeks (median, 81 weeks) after the last dose. Only 14% of women used this method continuously for one year after initiation (95% CI, 8–22%) (Box 5).

Acceptability of types of contraception

Individual semi-structured interviews were conducted with 20 Aboriginal women: 17 had previously been pregnant, and 15 had living children. Seventeen had used an etonogestrel implant and eight had used medroxyprogesterone. One woman had used an intra-uterine contraceptive device (IUCD), and another woman alluded to this: “It goes inside you” (interviewee p20). Eleven women were asked directly which methods they knew; they mentioned implants, injections, and one woman described an IUCD. None mentioned oral forms of contraception.

Most women spoke positively of the etonogestrel implant: “It’s good” (p1); “Better than taking tablets or getting needles” (p3); “Yeah, I had that one. That was right, no problem with that” (p13). Two women preferred medroxyprogesterone, as they did not like the feel of the implant: “Sometimes it confusing … and it feels like it stuck in your skin” (p9). Four women had had menstrual irregularities that resulted in cessation of use. When contraception had resulted in lighter periods, this was perceived as positive. Two women related stories of the implant “moving” (p6, p18), and one reported suspicions in the community that it had secondary purposes: “it controls them” (p11). When asked directly if there was any shame in having the implant in situ, six of six interviewees said it did not (“No, it’s in a good spot, private”: p20). The upper arm was the place of insertion with which all women were familiar, and gestures indicating the arm were used in conversation by women to indicate the implant. When asked if women were ever pressured to use contraception, five interviewees reported that some boyfriends wanted women to have their implant removed so that they could have a baby: “Yeah. There was a friend I had; her boyfriend wanted her to take it off, but she too young” (p15). No women reported receiving any unwanted attention because they had an implant in situ.

Mothers were asked if they would be happy for their daughters to use the etonogestrel implant for contraception. All replied positively, and two women described supporting their daughter when receiving the implant at the clinic: “Yeah, I took her to [the clinic] to get it” (p13). Women described the importance of being healthy and not too young when having babies, and of communication between mothers and daughters about contraception: “Good to learn these girls to look after their bodies” (p16); “girls too young have problems pushing them [babies] out” (p9).

Discussion

This is the first population-based study using medical records to determine rates of contraception use in Aboriginal Australian communities. We found a high uptake of LARCs (especially the etonogestrel implant) in three remote Western Desert communities, with one year continuation rates that compare favourably with those in other populations (87% in this study v 65–82%; details in Appendix).15–22 Together with the generally positive feedback from the community, this suggests good acceptance of LARCs, particularly among younger women.

Factors that may have contributed to the preferred use of the etonogestrel implant include the long term presence of a dedicated sexual health coordinator who provides counselling and referrals, and good access to trained inserters. Ready availability of the etonogestrel implant may predispose prescribers to recommend it; in comparison, the 900 km journey required to have an IUCD inserted probably contributes to their low use in these communities. During the final 12 months of the audit period, KAMS staff delivering sexual health services (including DF and EG) observed increasing numbers of women who presented unprompted for reproductive health consultations.

Key activities and outputs in sexual health program delivery include health promotion, staff development, and flexible service delivery, constituting a multifaceted approach to sexual health. This high acceptance of LARCs that we found and the changes to clinic practice as a result of these activities should inform future program design and delivery. This is particularly important when considering the high rates of teenage pregnancy in some Aboriginal populations,23 potentially indicating a group with unmet contraceptive needs that could be addressed by using LARCs.

There was less adherence to medroxyprogesterone injection. Possible explanations include the ambivalent contraceptive intent of the user, limited contraceptive literacy, and sub-optimal clinic recall systems. The infrequent use of emergency contraception warrants further exploration of patient acceptance and understanding, and of service delivery factors.

Current contraception was documented for only one-fifth of women in these communities, compared with two-thirds of all Australian women aged 18-49 years in 1998.24 This could also indicate unmet contraceptive needs. It could also reflect the relatively recent introduction of a locally based full-time general practitioner and the increased availability of trained inserters of LARCs. The interview participants were a group with a high rate of contraceptive use, and the voices of women not using contraception may have been missed.

This study was limited by the retrospective cohort design used to assess contraception use. Some under-reporting is likely, as contraception initiated at other health centres was not always documented, and some records were incomplete. Few women were recorded as having had permanent or surgical contraceptive procedures; procedures carried out elsewhere may not have been documented. However, our study provides a picture of contraception prescribing and use in a remote part of Australia that may well be relevant to other remote areas. Recent articles have highlighted the importance of understanding the values, attitudes and aspirations of a community when delivering reproductive health services.25

Some women described side effects of contraception, particularly menstrual side effects, but the implant was otherwise well tolerated. Where coercion to use contraception was reported, it related to partners desiring pregnancy and their pressure to cease contraception. None of the participating women reported any concerns that the presence of an implant attracted unwanted sexual attention.

While more than half of the women aged 20–24 years had some experience of contraception, its use by women under the age of 15 was uncommon. Lack of national prescribing data prevents direct comparison with other communities, but a national survey of high school students found that more than one-fifth of year 10 girls (median age, 15 years) had been sexually active, with the oral contraceptive pill the most frequent contraceptive method reported.26 This study suggests that while the choice of contraception method differs, the rate of contraception use among young women in these remote communities may not differ markedly from that of urban young non-Indigenous women. Our data show that, with sustained appropriate services, LARCs can be highly effective in remote Aboriginal communities. This supports a model of service delivery that promotes the reproductive health of Aboriginal women through community engagement and capacity building, aiming to broaden the focus of sexual health for women above and beyond the detection and management of STIs.

Box 1 –

Sexual and reproductive health activities conducted in the Western Desert region during the audit period

- Increased general practitioner workforce consistency, with decreasing use of locum practitioners from 2011

- Employment of a dedicated sexual health coordinator for the three communities from January 2013

- 61 community education sessions conducted 2013–2014, with a total attendance of 296 men and 607 women

- Upskilling of local nursing staff to perform pap smears and to insert and remove etonogestrel implants from 2013

- Production of Desert mob stories about good health, a collection of stories and art about questions that affect relationships (2013–2015)

- Engagement with external research projects; eg, The STI in remote communities: improved and enhanced primary health care (STRIVE) project, 201312

- Engagement with the Indigenous Hip Hop Project (2014)13

- Partnership development with several government and non-government agencies

- Pilot of after-hours clinics for young people from 2014

- Increased community engagement by clinic staff, with a focus on reducing stigma and encouraging regular check-ups and clinic attendance

Box 2 –

Contraception history of regular Aboriginal patients of the participating clinics, aged 12–50 years

Box 3 –

Prescription contraceptive history and current contraceptive use, at 1 September 2014*

|

Age group (years)

|

Number of women

|

Prescription contraception history at 1 September 2014, by method

|

|

Never used contraception

|

Etonogestrel implant†

|

MPA injection†

|

Intra-uterine device†

|

COCP†

|

|

|

12–14

|

61

|

52 (85%)

|

8 (13%)

|

1 (2%)

|

0

|

0

|

|

15–19

|

94

|

42 (45%)

|

48 (51%)

|

15 (16%)

|

0

|

2 (2%)

|

|

20–24

|

93

|

46 (49%)

|

44 (47%)

|

10 (11%)

|

0

|

2 (2%)

|

|

25–29

|

71

|

47 (66%)

|

19 (27%)

|

2 (3%)

|

0

|

4 (6%)

|

|

30–39

|

151

|

100 (66%)

|

44 (29%)

|

7 (5%)

|

0

|

2 (1%)

|

|

40–49

|

96

|

81 (84%)

|

7 (7%)

|

8 (8%)

|

1 (1%)

|

0

|

|

All

|

566

|

368 (65%)

|

170 (30%)

|

43 (8%)

|

1 (< 1%)

|

10 (2%)

|

|

Age group (years)

|

Number of women

|

Contraception in use at 1 September 2014, by method‡

|

|

Not using contraception

|

Etonogestrel implant

|

Etonogestrel implant, LTFU§

|

MPA injection

|

Intra-uterine device

|

Surgical/permanent

|

|

|

12–14

|

61

|

53 (87%)

|

6 (9%)

|

2 (4%)

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

15–19

|

94

|

59 (63%)

|

26 (28%)

|

5 (5%)

|

4 (4%)

|

0

|

0

|

|

20–24

|

93

|

71 (76%)

|

21 (23%)

|

1 (1%)

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

25–29

|

71

|

60 (85%)

|

8 (11%)

|

1 (1%)

|

0

|

0

|

2 (3%)

|

|

30–39

|

151

|

117 (77%)

|

29 (19%)

|

0

|

1 (1%)

|

0

|

4 (3%)

|

|

40–49

|

96

|

85 (89%)

|

3 (3%)

|

1 (1%)

|

4 (4%)

|

1 (1%)

|

2 (2%)

|

|

All

|

566

|

445 (79%)

|

93 (16%)

|

10 (2%)

|

9 (2%)

|

1 (<1%)

|

7 (<1%)

|

|

|

COCP = combined oral contraceptive pill; LTFU = lost to follow-up; MPA = medroxyprogesterone acetate. * All percentages are row percentages. † Women may have used more than one type of contraception. ‡ No women were current users of oral contraception. § Women lost to follow-up with an etonogestrel implant in situ at last contact.

|

Box 4 –

Continuation of use of etonogestrel implants by 170 Indigenous women in three Western Desert communities (Kaplan–Meier survival function)

Box 5 –

Continuation of use of medroxyprogesterone injections by 43 Indigenous women in three Western Desert communities (Kaplan–Meier survival function)

more_vert

more_vert