The known General practitioners spend time on patient care not claimable through Medicare (ie, not face-to-face consultations), but the extent of this non-billable time has not been quantified.

The new 12.1% of consultations were associated with non-billable time (average, 10.1 minutes per occasion) since the previous GP consultation with the patient. If claimable through Medicare this would equate to $10 000–$23 000 per annum per GP.

The implications GPs spend significant unpaid time on patient care between consultations. This is likely to increase as the population ages, with implications for planning changes to our current fee-for-service funding model.

Australian general practice is largely funded through the national health insurance scheme, Medicare, on a fee-for-service basis. General practitioners can claim payment from Medicare only for patient care that occurs during face-to-face consultations or for chronic disease management (eg, team care arrangements).

Generalisations about GP behaviour are occasionally expressed without supporting evidence. GPs are alleged to routinely provide “6-minute medicine”, in which patients are filtered through the consultation process, assessed, diagnosed and managed within this timeframe. Some GP consultations are of short duration; this is quite reasonable when otherwise well patients, for example, are renewing a prescription or receiving a seasonal influenza vaccination. However, the average duration of GP–patient consultations in Australia increased significantly between 2004–05 and 2013–14, and has been between 13.8 and 14.8 minutes for the past decade.1 Analyses of data from the national Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health (BEACH) program have identified factors that influence the length of a consultation,2 and also that GPs were more likely to claim a level B consultation (standard consultation under 20 minutes’ duration; rebate = $37.05) when a level C (professional attendance, lasting at least 20 minutes; rebate = $71.70) was more appropriate, given the actual time involved and the complexity of the consultation.3

The payment structure of Medicare, and the benefits and disadvantages of a fee-for-service system, rather than blended payments, salaried services or capitation systems,4–6 were widely debated by clinicians, economists and policy makers even before Medicare was introduced (as Medibank) in 1975.7 Anecdotal evidence suggests that most GPs spend time on patient care outside consultations, although they cannot claim payment for this care from the national health insurer.

At the request of the professional organisations associated with Australian general practice (the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners [RACGP] and the Australian Medical Association), a BEACH substudy investigated the time spent on patient care between consultations, for which GPs cannot claim financial compensation from Medicare (“non-billable time”). The aims of our study were to quantify the proportion of patients for whom GPs have spent non-billable time on patient care between consultations; to estimate the average amount of time GPs spent on patient care outside consultations; to estimate the monetary value of this time were it claimable; to determine the reasons or activities that require this time; and to determine which variables were independently associated with non-billable time for patient care.

Methods

The study was a Supplementary Analysis of Nominated Data (SAND) substudy of the BEACH program. BEACH is a continuous, national, cross-sectional survey of Australian general practice activity; its methods have been described in detail elsewhere.8 In brief, about 1000 randomly sampled, currently active recognised GPs are recruited each year. Participants record the details for 100 encounters with consenting, unidentified patients on structured paper forms. Information is collected about which problems were managed for each patient during each visit.

Throughout the program, a series of SAND substudies record aspects of patient health outside the content of the encounter. Between 1 April 2012 and 31 March 2014, recording kits were posted to 2500 GPs, and they were asked to record any non-billable time since their last consultation for 40 of their 100 surveyed patients. GPs were asked to record whether they had spent non-billable time on the management of any of the patient’s problems since the last time they saw the patient. The questions and instructions are shown in the Appendix. Multiple responses were allowed. The responses were recorded in free text, and subsequently classified according to chapters of the International Classification of Primary Care Version 2 (ICPC-2).10

To estimate the monetary costs of non-billable management, we applied the definitions of level A and level B Medicare items11 to occasions of non-billable time, as these would reflect the minimum and maximum amount that would be charged were the work claimable. Assuming the 40 recorded encounters were typical for the usual caseload of the GP, a monetary value was estimated based on the following:

-

the mean activity level of Australian GPs during 2013–14, measured as the number of Medical Benefits Scheme (MBS) GP service items claimed = 5132.3 claims per GP;9

-

the proportion of patient encounters associated with prior non-billable time;

-

the standard (level A) rebate: $16.95;

-

the standard (level B) rebate: $37.05.

Proportions and robust 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated in SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute) using survey procedures that adjusted for the cluster design of the study. Non-overlapping 95% CIs were deemed to indicate statistically significant differences, a criterion equivalent to P < 0.006.12 Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses (to calculate odds ratios, adjusted for clustering) identified characteristics independently associated with any non-billable time (v no non-billable time).

Interim results from this study were presented in 2013 at the RACGP conference GP13,13 and were the subject of an article in Australian Doctor in October 2013.14

Ethics approval

The BEACH program and all substudies have ethics approval and oversight from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Sydney (reference, 2012/130).

Results

Recording pads were returned by 1935 GPs (77.4% of 2500 recruited; response rates reported in detail elsewhere).9,15 Demographic data for the GP respondents are shown in Box 1. Questionnaires were completed for 66 458 patients. The age distribution of patients in the non-billable time subsample (SAND), the Medicare claims data (all Australian GPs), and all BEACH encounters for the same time period were similar, but the non-billable subsample had marginally fewer patients under 15 years of age and more patients aged 75 years old or more than the other two samples (data not shown). Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) patients were included in the BEACH and SAND samples, but not the Medicare claims sample. There were no significant sex distribution differences (data not shown).

At 8019 of the 66 458 patient encounters (12.1%), GPs had undertaken non-billable care of at least one health problem since the patient’s previous visit. Of these 8019, the number of non-billable minutes was not recorded for 479 (6.0%), and the GP was uncertain of the time spent for a further 657 (8.2%). At least one minute of non-billable time was recorded for the remaining 6883 patients (85.8%). The mean length of time spent on patient care between the current and the previous consultation was 10.1 minutes (range, 1–240 min; median, 6 min; interquartile range [IQR], 1–5 min).

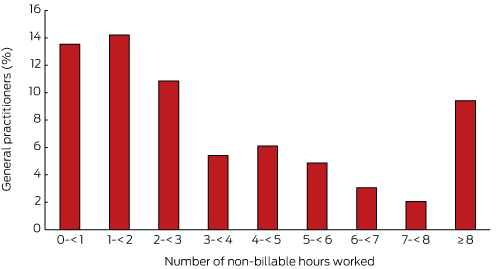

The distribution of non-billable time for patient care was skewed. Of the 1935 GPs surveyed, 30.5% did not record any non-billable time for any of their 40 patient encounters, 56.0% recorded at least one hour, 19.4% at least 5 hours, and nearly 10% recorded 8 or more hours (Box 2).

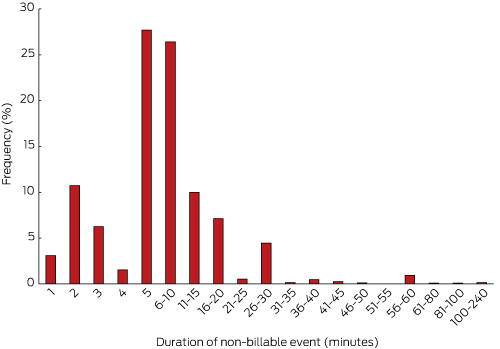

Box 3 summarises the frequency of non-billable time events for the 6883 occasions of at least one minute of non-billable time. Most of these events were of relatively short duration, with 75% lasting 10 minutes or less.

The mean non-billable time was 10.1 minutes per occasion (consistent with a level B Medicare item), and the median was 6.0 minutes (implying straightforward cases, and therefore a level A Medicare item). However, the complexity of these occasions was impossible to determine, so cost estimates were based on both level A and level B item rebates.

As Australian GPs claimed an average of 5132.3 general practice service items in 2013–14, and we found that GPs had undertaken non-billable care for 12.1% of patient encounters, we estimate that there were 5132.3 × 12.1% = 621.0 occasions of non-billable time per GP. The cost estimate for this time at the level A rebate would be: 621.0 × $16.95 = $10 525.95; at the level B rebate: 621.0 × $37.05 = $23 008.05.

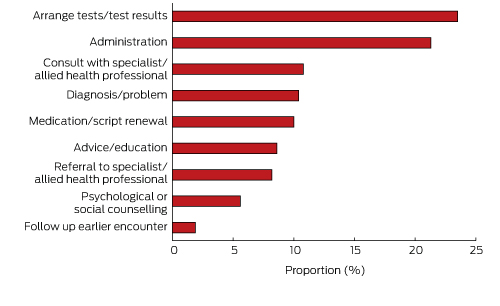

GPs recorded 8044 reasons for non-billable care between visits. Box 4 shows that nearly one-quarter related to arranging tests or delivering test results, 21.3% were for unspecified administrative tasks (eg, review report, insurance, phone call), and a similar proportion were for either consulting with or referring to specialists or allied health professionals. Medication or prescription renewals were common, as was advising or educating the patient about specific questions (eg, medication use, diet, care plan).

The specific problems dealt with were drawn from across the entire ICPC-2. The majority (86.4%) were coded to the “General and unspecified” chapter, 5.6% to the “Psychological” and “Social” chapters, and the remaining 8.0% were distributed across the other 14 chapters (data not shown). The psychological and social problems treated included depression, schizophrenia, dementia, anxiety, acute stress reaction, attempted suicide, counselling the terminally ill, their family members and the bereaved, physical abuse, family problems, anger management, and alcohol and other drug misuse (data not shown).

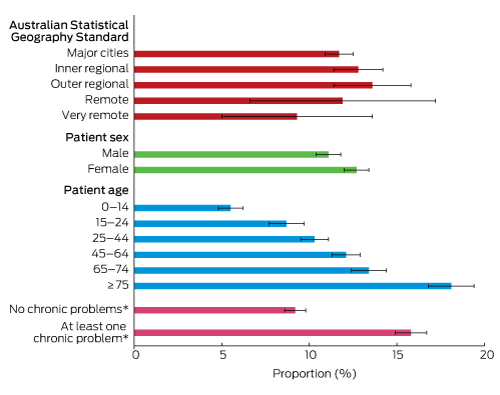

The mean number of non-billable minutes spent on patient care did not differ significantly with respect to patient age or sex, geographic location of the encounter (practice postcode), or whether at least one chronic problem was managed at the recorded encounter (data not shown). However, the descriptive analysis found that the likelihood that the GP spent any non-billable time on patient care since the last visit increased significantly with patient age, and was also significantly higher for female patients and for patients with at least one chronic problem managed at the recorded encounter (Box 5).

Variables included in the multivariate logistic regression analyses (corrected for the cluster survey design) were GP age and sex, patient age and sex, geographic location of the encounter, and whether or not any chronic conditions were managed at the recorded encounter. Non-billable time was independently associated with female GPs, younger GPs (under 55 years of age), female patients, patients aged 65 years or more, and patients having one or more chronic problems managed at the recorded encounter (Box 6).

Discussion

This study found that, on average, a GP will have more than 620 occasions each year in which they spend around 10 minutes outside consultations on various aspects of patient care; were this care claimable through Medicare, this time would return between $10 000 and $23 000. For some GPs, the amount foregone would be much higher than this average. The extra time is more likely to be provided by younger and female GPs, and for older patients, female patients, or patients with at least one chronic problem managed at a subsequent encounter. GPs are clearly spending a great deal of time on patient care for which they do not receive monetary compensation. Our study was undertaken during a period when Medicare rebate rates were frozen; further, 2014–15 was reported to be the year with the highest level of bulk-billing on record.16

Despite the high bulk-billing rate, Medicare is not the only source of income for GPs in Australia. Many doctors charge additional fees or claim incentive payments, and there are other factors that affect GP incomes.17 However, our study investigated care undertaken between consultations as lost opportunities for claimable income, regardless of whether extra charges were applied to normal consultations.

Australia has an ageing population, and Medicare and DVA data show that the frequency of GP visits increases exponentially with patient age.18 According to BEACH data, managing at least one chronic problem at GP–patient encounters has steadily increased over the past decade;1 90% of older people (65 years or over) have at least one chronic condition,19 and people from this age group increasingly present with several diagnosed chronic problems. In light of these factors, our findings suggest that occasions of non-billable time are likely to increase in number further. This is an inherent problem of the fee-for-service system, which largely restricts payments to face-to-face consultations. We have assumed that non-billable time could be reimbursed within the current fee-for-service model, but alternative payment structures might prove more equitable and efficient.

The RACGP medical homes model,20 one proposed pathway for improving health care and sustainability, involves enrolling or registering patients. There is evidence that informal patient registration already occurs; 96% of patients (and 98.6% of patients aged 65 years or more) have a practice that they visit regularly, allowing the practice to better manage their care.21 Knowing the patient and their problems is important in an ageing population with increasing multimorbidities to avoid treating individual problems in isolation, as can happen with fragmented care from multiple providers.

The Medicine in Australia: Balancing Employment and Life (MABEL) study found that GPs were generally more likely than other physicians (specialists, hospital non-specialists, specialists-in-training) to report that they did not undertake non-clinical work, such as education (teaching, research, continuing medical education) and management and administration.22 However, our results show that many GPs spend a considerable amount of time on administrative processes related to patients’ problems (21.3% of reasons for non-billable care). Many of these administrative procedures involved workers’ compensation, aged care, or disability assessments, and care and management plans for a variety of chronic conditions. These administrative procedures, as well as arranging tests, discussing test results, and communicating with specialists and allied health professionals, contributed more than half of the reasons for non-billable time. This clearly indicates that GPs are already very involved in integrating the care of their patients.

Further evidence that GPs provide holistic care was the non-billable time spent on advising and educating patients about various problems and counselling them for psychological or social problems (14.2% of all reasons). Not only was the time providing this care not claimable, it is likely to have been quite complex and, in some cases, stressful and confronting for the GP.

Our estimates and extrapolations are likely to be conservative. There is a possible element of recall error, as some time may have elapsed between visits by some of the recorded patients. Further, the raw data for Box 3 suggested an element of rounding bias with retrospective estimations (doctors tended to estimate non-billable time of greater than 45 minutes in multiples of 5 minutes), with no way to determine whether this reflected over- or underestimation.

The main limitation of the study was the design of the questionnaire form. The low number of responses about very young patients was unexpected, and we suspected that the placement of this question on the BEACH form — following the section on smoking and alcohol use by adult patients — led many GPs to assume that responses were to be recorded only for patients aged 18 years or more. However, there is no reason to believe the data collected for adult patients were unreliable.

Bias in the BEACH GP sample itself has been suggested, because “busy GPs” have no time to participate in the survey. Such bias would have particular implications for our study, as it is about GP time for clinical care. However, the activity levels of BEACH participants are compared annually with those of the Australian sample frame, and the numbers of service items claimed are similar.8

Our study has quantified the significant amount of unpaid time GPs spend on patient care between consultations, a situation likely to increase as the population ages and chronic multimorbidity becomes more prevalent. This unpaid time is an inherent problem of the fee-for-service system, which is almost exclusively restricted to paying for face-to-face consultations. Our findings should inform discussions about future funding models.

Box 1 –

Demographic data for the BEACH participant GPs and for all active recognised general practitioners in Australia (the sample frame), 2013–14

|

Variable

|

BEACH participant GPs, 2012–14*

|

All active Australian GPs, 2013–14†

|

P‡

|

|

|

Total number

|

1935

|

22 598

|

|

|

Sex

|

|

|

0.07

|

|

Men

|

1102 (57.0%)

|

13 353 (59.1%)

|

|

|

Women

|

833 (43.0%)

|

9245 (40.9%)

|

|

|

Age, years

|

|

|

0.002

|

|

< 35

|

141 (7.3%)

|

1873 (8.3%)

|

|

|

35–44

|

336 (17.5%)

|

4653 (20.6%)

|

|

|

45–54s

|

592 (30.8%)

|

6406 (28.3%)

|

|

|

≥ 55

|

853 (44.4%)

|

9666 (42.8%)

|

|

|

Missing

|

13

|

—

|

|

|

Place of graduation

|

|

|

< 0.001

|

|

Australia

|

1321 (68.5%)

|

14 132 (62.5%)

|

|

|

Overseas

|

607 (31.5%)

|

8466 (37.5%)

|

|

|

Missing

|

7

|

—

|

|

|

State or territory

|

|

|

0.20

|

|

New South Wales

|

679 (35.2%)

|

7384 (32.7%)

|

|

|

Victoria

|

440 (22.8%)

|

5587 (24.7%)

|

|

|

Queensland

|

399 (20.7%)

|

4557 (20.2%)

|

|

|

South Australia

|

136 (7.0%)

|

1825 (8.1%)

|

|

|

Western Australia

|

175 (9.1%)

|

2108 (9.3%)

|

|

|

Tasmania

|

54 (2.8%)

|

601 (2.7%)

|

|

|

Australian Capital Territory

|

33 (1.7%)

|

355 (1.6%)

|

|

|

Northern Territory

|

13 (0.6%)

|

181 (0.8%)

|

|

|

Missing

|

6

|

—

|

|

|

Australian Standard Geographical Classification§

|

|

0.02

|

|

Major cities of Australia

|

1329 (68.9%)

|

15 970 (70.7%)

|

|

|

Inner regional Australia

|

392 (20.3%)

|

4301 (19.0%)

|

|

|

Outer regional Australia

|

183 (9.5%)

|

1869 (8.3%)

|

|

|

Remote Australia

|

19 (1.0%)

|

275 (1.2%)

|

|

|

Very remote Australia

|

6 (0.3%)

|

180 (0.8%)

|

|

|

Missing

|

6

|

3

|

|

|

|

BEACH = Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health study. * Data drawn from the BEACH GP profile completed by each participating GP; missing data removed. † All GPs who claimed at least 375 Medical Benefits Scheme GP consultation services during the most recent 3-month Medicare Australia data period (data provided by the Australian Government Department of Health); missing data removed. ‡ χ2 test. § Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ABS Cat. No. 1216.0). Canberra: ABS, 2011.

|

Box 2 –

Distribution of non-billable time for patient care, as reported by 1935 BEACH participant general practitioners

Box 3 –

Frequency of 6883 non-billable time events by BEACH participant general practitioners, by duration (minimum duration: one minute)

Box 4 –

Reasons nominated by 1935 BEACH participant general practitioners for providing non-billable care

Box 5 –

The proportion of patient encounters associated with non-billable care since the previous consultation: characteristic-specific likelihood

Box 6 –

Demographic characteristics associated with any non-billable time between consultations

|

Characteristic

|

Adjusted odds ratio*

|

P

|

|

|

Female GP (v male)

|

1.43 (1.25–1.62)

|

< 0.001

|

|

GP aged 55 years or more (v under 55 years)

|

0.87 (0.76–0.99)

|

0.03

|

|

Female patient (v male patient)

|

1.08 (1.02–1.15)

|

0.01

|

|

Patient aged 65 years or more (v under 65 years)

|

1.42 (1.32–1.54)

|

< 0.001

|

|

At least one chronic problem managed at the recorded encounter (v no chronic problem)

|

1.70 (1.58–1.82)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Patient in major cities (v non-major cities)

|

1.08 (0.95–1.23)

|

0.23

|

|

|

* Multivariate logistic regression model, corrected for cluster survey design.

|

![]() This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

more_vert

more_vert