Minimal trauma fractures remain a major cause of morbidity in Australia, affecting one in two women and one in four men over the age of 60 years.1 Mortality is increased after all minimal trauma fractures, even after minor fractures.2 Hip fractures are particularly devastating, leading to decreased quality of life, increased mortality and loss of functional independence.3

Defining osteoporosis

Bone mineral density (BMD) is expressed in relation to either “young normal” adults of the same sex (T score) or to the expected BMD for the patient’s age and sex (Z score). Osteoporosis is defined as a T score ≤ 2.5 SDs below that of a “young normal” adult, with fracture risk increasing twofold to threefold for each SD decrease in BMD.4,5 A BMD Z score less than −2 indicates that BMD is below the normal range for age and sex, and warrants a more intensive search for secondary causes. Importantly, osteoporosis is also diagnosed after a minimal trauma fracture, irrespective of the patient’s T score.

Absolute fracture risk

Treatment for osteoporosis is recommended for patients with a high absolute fracture risk. This includes older Australians (post-menopausal women and men aged over 60 years) with T scores ≤ −2.5 at the lumbar spine, femoral neck or total hip, and patients with a history of a minimal trauma fracture.6 There is a major gap between evidence and treatment in secondary fracture prevention, with fewer than 20% of patients presenting with a minimal trauma fracture being treated or investigated for osteoporosis.7,8 However, it is important that patients with a low fracture risk, including younger women without clinical risk factors and T scores ≤ −2.5 at “non-main-sites” (eg, lateral lumbar spine or Ward’s triangle in the hip) are not treated.9 Absolute fracture risk calculators incorporate osteoporosis risk factors with BMD to stratify fracture probability.10 It is therefore important for clinicians to assess absolute fracture risk. Two of several absolute fracture risk calculators are commonly used to aid clinicians in this regard: the Garvan Fracture Risk Calculator11 and the Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) developed by the World Health Organization.

The Garvan Fracture Risk Calculator estimates absolute fracture risk over 5 and 10 years (http://www.garvan.org.au/bone-fracture-risk/). It may be used in men and women aged over 50 years, and incorporates age, sex, BMD at the spine or femoral neck, falls and fracture history. A potential limitation of this tool is that it does not include other clinical risk factors. The country-specific FRAX tool calculates the 10-year probability of hip fracture and major osteoporotic fracture in patients aged 40–90 years. It incorporates femoral neck BMD with ten clinical risk factors. Limitations include underestimation of fracture risk in patients with multiple minimal trauma fractures, an inability to adjust the risk for dose-dependent exposure, a lack of validation for use with BMD of the spine, and exclusion of falls.

Role of fracture risk calculators in 2016

The role of absolute fracture risk calculators in clinical practice is evolving. In addition to their individual limitations, there is a lack of evidence that their use leads to effective targeting of drug therapy to those deemed to be at high risk of fracture,12 and prospective studies are needed. In particular, country-specific intervention thresholds based on absolute fracture risk need to be validated clinically. However, fracture risk calculators are useful for identifying patients with low fracture risk who do not require treatment.

Special patient groups

Limited evidence-based guidance is available for treating osteoporosis in several groups, including patients with post-transplantation osteoporosis, type 1 diabetes mellitus, chronic kidney disease (creatinine clearance < 30 mL/minute), neurological, respiratory and haematological diseases, and young adults and pregnant women. Such patients require individualised management.

Osteoporosis prevention using non-pharmacological therapies

Lifestyle approaches (adequate dietary calcium intake, optimal vitamin D status, participation in resistance exercise, smoking cessation, avoidance of excessive alcohol, falls prevention) act as a framework for improving musculoskeletal health at a population-based level.6,13–16

Calcium and vitamin D

The current Australian recommended daily intake (RDI) of calcium is 1300 mg per day for women aged over 51 years, 1000 mg per day for men aged 51–70 years and 1300 mg per day for men aged over 70 years.17 Adverse effects of calcium supplementation include gastrointestinal bloating, constipation,18 and renal calculi.19 There is controversy about the efficacy of calcium in preventing osteoporotic fractures.6,19,20 Further work is required with studies powered to investigate cardiac outcomes in men and women receiving calcium supplementation to meet current RDIs. Higher dietary calcium intake is also associated with reductions in mortality, cardiovascular events and strokes.21 Dietary sources of calcium are the preferred sources. Calcium supplementation should be limited to 500–600 mg per day, and used only by those who cannot achieve the RDI with dietary calcium.15

The main source of vitamin D is through exposure to sunlight. Institutionalised or housebound older people are at particularly high risk of vitamin D deficiency. Inadequate vitamin D status is defined as a serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) level < 50 nmol/L in late winter/early spring; in older individuals such inadequate vitamin D levels are associated with muscular weakness and decreased physical performance.22 Increased falls and fractures occur at 25(OH)D levels < 25–30 nmol/L.23,24 Adults aged 50–70 years and those over 70 years require at least 600 IU to 800 IU of vitamin D3 daily, with larger daily doses required to treat vitamin D deficiency.25

Exercise

Community-based high speed, power training, multimodal exercise programs increase BMD and muscle strength, with a trend to falls reduction.26 Thus, exercise is recommended both to maintain bone health and reduce falls. It should be individualised to the patient’s needs and abilities, increasing progressively as tolerated by the degree of osteoporosis-related disability.

Falls prevention

Falls are the precipitating factor in nearly 90% of all appendicular fractures, including hip fractures,3 and reducing falls risk is critical in managing osteoporosis. Reducing the use of benzodiazepines, neuroleptic agents and antidepressants reduces the risk of falls,27 and, among women aged 75 or more years, muscle strengthening and balance exercises reduce the risk of both falls and injuries.28

Antiresorptive therapy for osteoporosis

Post-menopausal osteoporosis results from an imbalance in bone remodelling, such that bone resorption exceeds bone formation. Antiresorptive drugs decrease the number, activity and lifespan of osteoclasts,29 preserving or increasing bone mass with a resulting reduction in vertebral, non-vertebral and hip fractures. These drugs include bisphosphonates (oral or intravenous),30–35 oestrogen36,37 and selective oestrogen receptor-modulating drugs,38 strontium ranelate and denosumab, a human monoclonal antibody against receptor activator of nuclear factor κB-ligand (RANKL).39

Antiresorptive treatments for osteoporosis are approved for reimbursement on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) for men and post-menopausal women following a minimal trauma fracture, as well as for those at high risk of fracture, on the basis of age (> 70 years) and low BMD (T score < −2.5 or −3.0). Bisphosphonates are also approved for premenopausal women who have had a minimal trauma fracture. In patients at high risk of fracture, osteoporosis therapy reduces the risk of vertebral fractures by 40–70%, non-vertebral fractures by about 25%, and hip fractures by 40–50%.30–40

Bisphosphonates

Mechanism of action and efficacy. Bisphosphonates are stable analogues of pyrophosphate. They bind avidly to hydroxyapatite crystals on bone and are then released slowly at sites of active bone remodelling in the skeleton, leading to recirculation of bisphosphonates. The terminal half-lives of bisphosphonates differ; for alendronate it is more than 10 years,41 while for risedronate it is about 3 months.42

Alendronate prevents minimal trauma fractures. Therapy with alendronate reduces vertebral fracture risk by 48% compared with placebo. Similar reductions in the risk of hip and wrist fractures were seen in women treated with alendronate who had low BMD and prevalent vertebral fractures.33,34,43 A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of post-menopausal women assigned to risedronate therapy or placebo for 3 years showed vertebral and non-vertebral fracture risks were respectively reduced by 41% and 39% by risedronate.35 Three years of treatment with zoledronic acid in women with post-menopausal osteoporosis reduced the risk of morphometric vertebral fracture by 70% compared with placebo, and reduced the risk of non-vertebral and hip fracture by 25% and 41% respectively.30

Adverse effects. The main potential adverse effects of oral bisphosphonates are gastrointestinal (including reflux, oesophagitis, gastritis and diarrhoea). Oral bisphosphonates should not be given to patients with active upper gastrointestinal disease, dysphagia or achlasia. Intravenous bisphosphonates are associated with an acute phase reaction (fever, flu-like symptoms, myalgias, headache and arthralgia) in about a third of patients, typically within 24–72 hours of receiving their first infusion of zoledronic acid, but is reduced significantly on subsequent infusions.30 Treatment with antipyretic agents, including paracetamol, improves these symptoms. Treatment with bisphosphonates may also lower serum calcium concentrations, but this is uncommon in the absence of vitamin D deficiency.44,45 Bisphosphonates are not recommended for use in patients with creatinine clearance below 30–35 mL/min.

Less common adverse effects associated with long term bisphosphonate therapy include osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) and atypical femoral fracture (AFF). Overemphasis of these uncommon adverse effects by patients has led to declining osteoporosis treatment rates.46

Jaw osteonecrosis. ONJ is said to occur when there is an area of exposed bone in the maxillofacial region that does not heal within 8 weeks after being identified by a health care provider, in a patient who was receiving or had been exposed to a bisphosphonate and did not have radiation therapy to the craniofacial region.47 Risk factors for ONJ include intravenous bisphosphonate therapy for malignancy, chemotherapeutic agents, duration of exposure to bisphosphonates, dental extractions, dental implants, poorly fitting dentures, glucocorticoid therapy, smoking, diabetes and periodontal disease.48,49 The risk of ONJ is about 1 in 10 000 to 1 in 100 000 patient-years in patients taking oral bisphosphonates for osteoporosis.47 Given the prolonged half-life of bisphosphonates, temporary withdrawal of treatment before extractions is unlikely to have a significant benefit and is therefore not recommended.50

Atypical femur fractures. Clinical trial data clearly support the beneficial effect of bisphosphonates in preventing minimal trauma fractures. However, oversuppression of bone remodelling may allow microdamage to accumulate, leading to increased bone fragility.51 Cases of AFF and severely suppressed bone remodelling after prolonged bisphosphonate therapy52 have prompted further research and recent guideline development.53 However, this finding is not universal. AFFs occur in the subtrochanteric region or diaphysis of the femur and have unique radiological features, including a predominantly transverse fracture line, periosteal callus formation and minimal comminution, as shown in Box 1.53 AFFs have been reported in patients taking bisphosphonates and denosumab, but about 7% of cases occur without exposure to either drug. AFFs appear to be more common in patients who have been exposed to long term bisphosphonate therapy, with a higher risk (113 per 100 000 person-years) in patients who receive more than 7–8 years of therapy.53 Although many research questions remain unanswered, including aetiology, optimal screening and management of these fractures, the risk of a subsequent AFF is reduced from 12 months after cessation of bisphosphonate treatment.

Duration of therapy. Concerns about the small but increased risk of adverse events after long term treatment with bisphosphonates (Box 2) have led to the development of guidelines on the optimal duration of therapy.54 For patients at high risk of fracture, bisphosphonate treatment for up to 10 years (oral) or 6 years (intravenous) is recommended. For women who are not at high risk of fracture after 3 years of intravenous or 5 years of oral bisphosphonate treatment, a drug holiday of 2–3 years may be considered (Box 3). However, it is critical to understand that “holiday” does mean “retirement”, and those patients should continue to have BMD monitoring after 2–3 years.

Hormone replacement therapy

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is effective in preventing and treating post-menopausal osteoporosis. Benefits need to be balanced against thromboembolic and vascular risk, breast cancer risk (for oestrogen plus progesterone), and duration of therapy. HRT is most suitable for recently menopausal woman (up until age 59 years), particularly for those with menopausal symptoms. In women with an early or premature menopause, HRT should be continued until the average age of menopause onset (about 51 years), or longer in the setting of a low BMD. Oral or transdermal oestrogen therapy (in women who have had a hysterectomy) and combined oestrogen and progesterone therapy preserve BMD,55 and were also shown to reduce the risk of hip, vertebral and total fractures compared with placebo in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI).37,56

In the initial WHI analysis, combined oral oestrogen and progesterone therapy for 5.6 years in post-menopausal women aged 50–79 years (who were generally older than women who used HRT for control of menopausal symptoms), many of whom had cardiovascular risk factors, was shown to increase the risk of breast cancer, stroke and thromboembolic events.57 However, subsequent reanalysis of WHI data has established the efficacy and safety of HRT in younger women up until 10 years after menopause, or the age of 59 years, when the benefits of treatment outweigh the risks. In women with a history of hysterectomy, oral oestrogen therapy alone has a better benefit–risk profile, with no increases in rates of breast cancer or coronary heart disease.56

Women commencing HRT should be fully informed about its benefits and risks. Cardiovascular risk is not increased when therapy is initiated within 10 years of menopause,58,59 but the risk of stroke is elevated regardless of time since menopause. It is also recommended that doctors discuss smoking cessation, blood pressure control and treatment of dyslipidaemia with women commencing HRT.

Selective oestrogen receptor modulator (SERM) drugs

The SERM raloxifene has beneficial oestrogen-like effects on bone, but has oestrogen antagonist activity on breast and endometrium. Treatment with raloxifene for 3 years reduced vertebral fractures by 30–50% compared with placebo in post-menopausal women.38 However, there was no reduction in non-vertebral fractures. Consequently, raloxifene is useful in post-menopausal women with spinal osteoporosis, particularly those with an increased risk of breast cancer. Raloxifene therapy is also associated with a 72% reduction in the risk of invasive breast cancer.60 Raloxifene may exacerbate hot flushes, and women receiving raloxifene have a greater than threefold increased incidence of thromboembolic disease, comparable with those receiving HRT.36,56 Raloxifene therapy is also associated with an increased risk of stroke,61 particularly in current smokers.

Denosumab

Denosumab is a human monoclonal antibody with specificity for RANKL, which stimulates the development and activity of osteoclasts. Denosumab mimics the endogenous inhibitor of RANKL, osteoprotegerin, and is given as a 60 mg subcutaneous injection once every 6 months. Denosumab reduces new clinical vertebral fractures by 68%, with a 40% reduction in hip fracture and a 20% reduction in non-vertebral fractures compared with placebo over 3 years.39,62

The adverse effects of denosumab include small increases in the risks of eczema, cellulitis and flatulence.39 Hypocalcaemia, particularly in patients with abnormal renal function, has also been reported,63 and denosumab is contraindicated in patients with hypocalcaemia. Jaw osteonecrosis has been reported in patients receiving denosumab for osteoporosis, as have AFFs.64,65

Strontium ranelate

Strontium ranelate increases bone formation markers and reduces bone resorption markers, but is predominantly antiresorptive, as increases in the rate of bone formation have not been demonstrated.66 Strontium ranelate significantly reduces the risk of vertebral and non-vertebral fractures.67–69 The most frequent adverse effects associated with strontium ranelate are nausea, diarrhoea, headache, dermatitis and eczema.67,68 Cases of a rare hypersensitivity syndrome (drug reaction, eosinophilia and systemic symptoms [DRESS]) have been reported, and strontium ranelate should be discontinued if a rash develops. Strontium ranelate treatment was associated with an increased incidence of venous thromboembolism70 and, more recently, with a small increase in absolute risk of acute myocardial infarction. Strontium ranelate is contraindicated in patients with uncontrolled hypertension and/or a current or past history of ischaemic heart disease, peripheral arterial disease and/or cerebrovascular disease.71 This drug is now a second-line treatment for osteoporosis, only used when other medications for osteoporosis are unsuitable, in the absence of contraindications.

Anabolic therapy for osteoporosis

Teriparatide

Teriparatide increases osteoblast recruitment and activity to stimulate bone formation.40 In contrast to antiresorptive agents, which preserve bone microarchitecture and inhibit bone loss, teriparatide (recombinant human parathyroid hormone [1–34]) stimulates new bone formation and improves bone microarchitecture. Teriparatide reduced the risk of new vertebral fractures by 65% in women with osteoporosis who have had one or more baseline fractures40 and also reduced new or worsening back pain. Non-vertebral fractures are also reduced by 53% by teriparatide, but studies have been underpowered to detect reductions in the rate of hip fracture. Side effects include headache (8%), nausea (8%), dizziness and injection-site reactions. Transient hypercalcaemia (serum calcium level, > 2.60 mmol/L) after dosing also occurred in 3–11% of patients receiving teriparatide.

Teriparatide has a black box warning concerning an increased incidence of osteosarcoma in rats that were exposed to 3 and 60 times the normal human exposure over a significant portion of their lives. Teriparatide is therefore contraindicated in patients who may be at increased risk of osteosarcoma, including those with a prior history of skeletal irradiation, Paget’s disease of bone, an unexplained elevation in bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, bone disorders other than osteoporosis, and in adolescents and children.

In Australia, the maximum lifetime duration of teriparatide therapy is 18 months. However, the antifracture benefit increases the longer the patient remains on treatment, with non-vertebral fractures being reduced for up to 2 years of treatment compared with the first 6 months of treatment, and for up to 2 years following cessation of treatment.72 In addition, increases in the rates of trabecular and cortical bone formation continue for up to 2 years of treatment, refuting the outmoded concept of a limited “anabolic window” of action for this drug.73 Importantly, following teriparatide therapy, the accrued benefits will be lost if antiresorptive therapy is not immediately instituted. Teriparatide reimbursement through the PBS is restricted to patients who have had two minimal trauma fractures and who have a fracture after at least a year of antiresorptive therapy, and who have a BMD T score below −3. However, the rate of teriparatide use in Australia is among the lowest in the world (David Kendler, University of British Columbia, Canada, personal communication).

Future directions

Three new anti-osteoporosis drugs are in clinical development.

“Selective” antiresorptive drugs

A novel “selective” antiresorptive drug, odanacatib, is a cathepsin K inhibitor that has the advantage of not suppressing bone formation, as do traditional or “non-selective” antiresorptive drugs. Clinical trial data in the largest ever osteoporosis trial, published in abstract form, show that odanacatib, given as a weekly tablet, reduces vertebral, non-vertebral and hip fractures with risk reductions similar to those seen with bisphosphonates. Adverse events were reported and include atypical femur fractures, morphea and adjudicated cerebrovascular events.74 The benefit–risk profile of this drug is currently being clarified.

Anabolic drugs

The two other new drugs are anabolic agents. Abaloparatide, an analogue of parathyroid hormone-related protein (1–34), selectively acts on the type 1 parathyroid hormone receptor to stimulate bone formation. It is given as a daily injection.75 It reduces vertebral and non-vertebral fractures, but data for hip fracture are lacking.76 Abaloparatide reduced major osteoporotic fractures by 67% compared with placebo.77 Abaloparatide will also have a black box warning about osteogenic sarcoma in rats. The final drug, romosozumab, is a monoclonal antibody that targets an inhibitor of bone formation, sclerostin, and is given as 2-monthly injections for 12 months. Trial data comparing reductions in fractures with placebo are awaited, and a head-to-head trial comparing the antifracture efficacy of romosozumab with alendronate is ongoing.

Conclusion

Osteoporosis treatment represents a missed opportunity for medical practitioners. Despite a growing number of effective therapies, where the benefits far outweigh the risks, only a minority of patients presenting to the health care system with minimal trauma fractures are being either investigated or treated for osteoporosis.

The time to close this gap between evidence and treatment is long overdue and will require systems-based approaches supported by both the federal and state governments. One such approach is fracture liaison services, which have proven efficacy in cost-effectively reducing the burden of fractures caused by osteoporosis, and are increasingly being implemented internationally. General practitioners also need to take up the challenge imposed by osteoporosis and become the champions of change, working with the support of specialists and government to reduce the burden of fractures caused by osteoporosis in Australia.

Box 1 –

Bilateral atypical femoral fractures in an older woman after bisphosphonate therapy for 9 years*

* Note the characteristic findings of a predominantly transverse fracture line, periosteal callus formation and minimal comminution on the left, and the periosteal reaction on the lateral cortex on the right femur, indicating an early stress fracture.

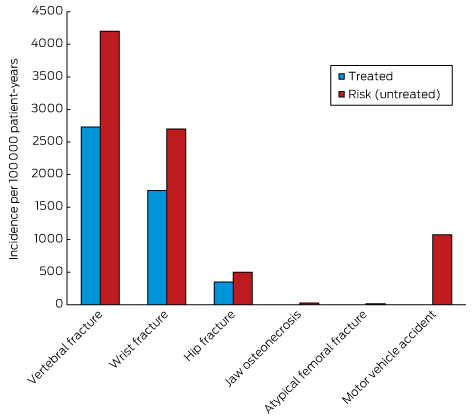

Box 2 –

Balancing benefits and risks of bisphosphonate therapy with other lifetime risks*

* Adapted from Adler, et al.54

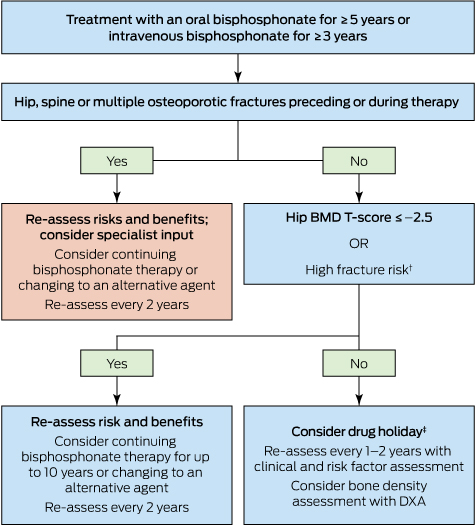

Box 3 –

Approach to the management of post-menopausal women on long term bisphosphonates therapy for osteoporosis*

DXA = dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. * Adapted from Adler, et al.54 † Includes age > 70 years; clinical risk factors for fracture and osteoporosis; fracture risk score on fracture risk calculation tools above the Australian treatment threshold. ‡ Cessation of treatment for 2–3 years.

more_vert

more_vert