The known Older people are using emergency medical services at increasing rates. Little is known about their use of alternative care options, such as after-hours primary care and deputising services.

The new Residents of aged care facilities more frequently used medical deputising services than patients dwelling in the community; their increase in use over 2008–2012 was nearly double that of older people in the community.

The implications The increasing use of medical deputising services by older patients highlights the need to better integrate them with existing services, and for oversight to ensure their appropriate use.

Australian acute health care services handle an ever increasing number of emergency department (ED) presentations, especially by older patients.1 Similarly, the need for emergency ambulance transportation for people aged 85 years or more has risen dramatically.2 With an ageing population, the demand on ED services is expected to increase even further,3 but an estimated 40% of all ED presentations are potentially avoidable and could be handled safely by primary care services.4 Using emergency services for non-emergency conditions places an excessive burden on ED resources, diminishes the capacity of ED staff to respond effectively to serious, time-critical emergencies, and compromises patient safety.5,6

A range of alternative after-hours primary care service models could reduce avoidable demands on emergency services, including medical deputising services, telephone triage and advice lines, minor injuries units, general practitioner clinic cooperatives, and co-located GP clinics in hospitals.7–9 For their accreditation, operators of general practices are required to make appropriate arrangements for after-hours care of patients. However, accessibility to after-hours primary care services can be particularly challenging for older patients, who are more likely to need them because of comorbid conditions, increased medical needs, difficulties with transport, or a reluctance to leave their home alone at night.10 The delivery of more appropriate after-hours primary care for this age group through home visits by a GP is one practical option.

Several medical deputising services arrange after-hours home visits by GPs. Patients may be visited by a locum GP employed by the deputising service, or it may act as an answering service for the person’s regular GP if they are available to attend their patient.8 In Australia, the proportion of GPs working in practices using medical deputising services has increased significantly over the past decade, in contrast to the declining fraction who work in practices that provide after-hours care, either autonomously or in cooperation with other practices.11 The increased use of medical deputising services for after-hours care may be due to changes in policy that encourage GP support organisations (formerly Medicare Locals, now restructured as Primary Health Networks) to improve access to after-hours primary health care services by promoting medical deputising services9,12 and lifting the ban on medical deputising services directly advertising their services to the community, so that they need not rely on GP referrals alone.

Although the use of medical deputising services in Australia has increased, little has been published on how they are used for after-hours care by older patients, who both comprise a growing proportion of the population and contact emergency services with increasing frequency.2,3 We therefore examined how older people used a medical deputising service in Melbourne, and compared differences in patterns for people living in residential aged care facilities (RACFs) and private residences. In 2011, 94% of Australians aged 65 years or more lived in private dwellings and about 4% in RACFs, including nursing homes and accommodation for the retired or aged, but excluding self-contained units in retirement villages.13

Methods

This study was part of a larger, four-phase research program investigating strategies for reducing avoidable presentations by older people for emergency care treatment (REDIRECT).14

Data

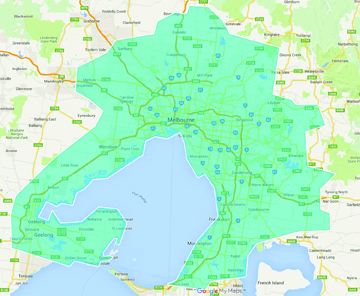

We conducted a retrospective analysis of administrative data collected by the Melbourne Medical Deputising Service (MMDS). During 2008–2012, MMDS was one of the major medical deputising services in Victoria, serving greater metropolitan Melbourne and its surrounding areas, including Geelong (Box 1). Telephone requests for medical care were triaged by an MMDS operator as being appropriate for an after-hours GP visit, and then logged as a booking.

According to criteria set by the federal government, the after-hours period for health care was defined as follows:15

-

Weekdays: before 1 May 2010, outside 8 am–8 pm; from 1 May 2010, outside 8 am–6 pm;

-

Saturdays: before 1 May 2010, outside 8 am–1 pm; from 1 May 2010, outside 8 am–12 noon; and

-

Sundays and public holidays: all day.

GP home consultations (bulk-billed for holders of Department of Veterans’ Affairs [DVA] cards or Commonwealth Seniors Health Cards) were held during these after-hours periods, but MMDS call centres were open to receive calls and to log bookings 2 hours prior to the start of weekday and Saturday MMDS consultation times, and all day on Sundays and public holidays.

All bookings logged for patients aged 70 years or more during 1 January 2008 – 31 December 2012 were included in our analysis. Routinely collected patient information for each telephone booking included demographic data, accommodation type (RACF or non-RACF), and the patient’s usual GP. Caller information was also recorded.

When calculating telephone bookings rates, we used Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) annual population data to estimate the number of people aged 70 years or more residing in the MMDS coverage area,16 which we defined as encompassing the following ABS geographical units: Greater Melbourne (Greater Capital City Statistical Area [GCCSA] geographical unit code 2GMEL), Geelong (Statistical Area Level 3 [SA3] geographical unit code 20302), and Portarlington, Clifton Springs, Queenscliff and Ocean Grove-Barwon Heads (SA2 units) (Box 1).

To assess the influence of socio-economic status, patients were allocated to Index of Relative Socio-Economic Disadvantage (IRSD) deciles (ranked within Victoria)17 according to the postcode of their usual place of residence. Socio-economic status deciles were compiled into quintiles, the first quintile corresponding to the most disadvantaged 20% of the population, and the fifth quintile to the 20% least disadvantaged.

Statistical analyses

The primary outcome was a telephone booking for an after-hours GP visit. The primary exposure variable of interest was the patient’s accommodation type. Data were summarised as descriptive statistics. The demographic characteristics of RACF and non-RACF patients and their utilisation of the MMDS service were compared in cross-tabulations. For categorical data, frequencies and proportions were calculated and associations assessed in χ2 tests. For continuous data, means and standard deviations were calculated, and differences between groups of normally distributed data compared in t tests. All analyses were performed in Stata 13.1 (StataCorp).

Ethics approval

Approval for this study was obtained from the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (reference, CF13/3315–2013001738).

Results

Of the 357 112 bookings logged by MMDS for people aged 70 years or over, 290 264 (81.3%) were from RACFs (Box 2). The mean age of RACF patients was higher than for non-RACF patients, although the range (70–99 years) was similar for both groups. More women than men, and more people in the least disadvantaged IRSD quintile than in any other single quintile used the MMDS, irrespective of accommodation type. For RACF patients, the caller was typically a member of staff or the ambulance service; for non-RACF patients, callers included the person themselves or a family member, neighbours, or a district nurse or ambulance service staff member.

Most MMDS bookings resulted in a locum GP visiting the patient (RACF, 91%; non-RACF, 82%). An urgent transfer to hospital was organised for 6% of non-RACF patients, compared with 3% of RACF patients. Conversely, Ambulance Victoria, which triages non-emergency patients to GP services, referred 5% of non-RACF patients and 0.1% of RACF patients to the MMDS.

A small proportion of bookings were either cancelled or not acted upon (RACF, 8%; non-RACF, 16%). Reasons for cancellations included “no longer required: feeling better”, “unable to wait for a locum”, “called an ambulance”, “cancelled by district nurse”, “going to sleep”, “didn’t want to see a locum, only their usual GP”, and “no answer at door or on phone”.

MMDS booking rates

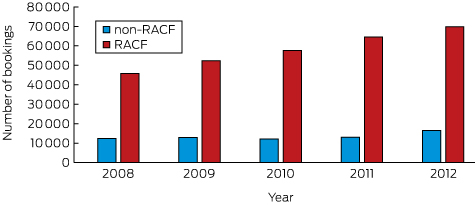

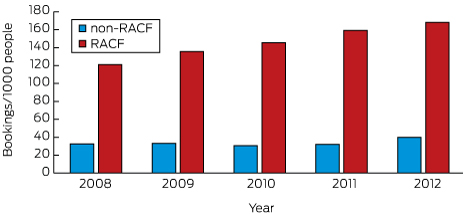

The number of MMDS bookings for RACF patients increased from 45 828 in 2008 to 69 901 in 2012; this 53% increase was significantly greater than the 34% increase for non-RACF patients (P < 0.001; Box 3). The booking rate for RACF patients increased during this period from 121 to 168 per 1000 people aged 70 years or more; the booking rate for non-RACF patients increased from 33 to 40 per 1000 people aged 70 years or more, but the trend was less consistent (Box 4). There was a relative increase of 39% in the rate of MMDS bookings for RACF residents between 2008 and 2012, and of 21% for non-RACF patients.

Peak use

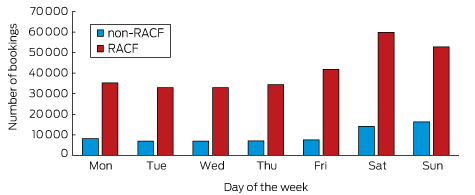

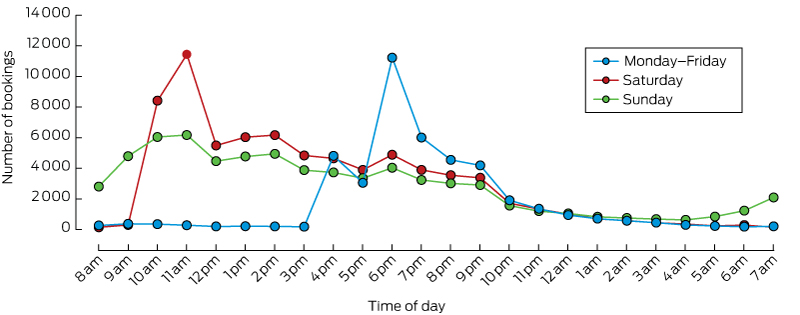

MMDS bookings for an after-hours GP visit were most frequent on Saturdays and Sundays (Box 5). The peak booked consultation times were 6 pm on weekdays and 11 am on Saturdays and Sundays (Box 6). After-hours GP bookings were lowest during 1 am–5 am.

Discussion

Our study is the first to examine the use of an after-hours medical deputising service in Melbourne by older people. Most MMDS bookings were for people living in RACFs, with a steady increase in the frequency of bookings between 2008 and 2012. The booking rate for people not living in RACFs began to increase from 2010, coinciding with health reforms that included Medicare Locals facilitating regional after-hours access to primary care. Most MMDS bookings resulted in a locum GP visit, and only a small proportion of visits required an urgent transfer to hospital. Older women and individuals living in higher areas of higher socio-economic status were more likely to avail themselves of MMDS services.

The higher booking rate for patients in RACFs than for those in private dwellings (168 v 40 per 1000 people aged 70 years or more in 2012) probably reflects their greater frailty and poorer health,18,19 but may also reflect the lower number of GPs providing care to people in RACFs.20 Conversely, lack of knowledge about alternative after-hour primary care services among people not living in RACFs may have contributed to their lower booking rates.9,21 Cost is unlikely to be a factor for this group (including those living in areas of lower socio-economic status), as home visits to those with Seniors Health Cards or DVA cards were bulk-billed. The large increases in the relative booking rate for both RACF and non-RACF residents (40% and 20% respectively) indicate that the deputising service is responding to a growing and appropriate need, as only a small proportion of bookings resulted in an urgent transfer to hospital.

Six per cent of bookings for people not living in RACFs resulted in an urgent transfer to hospital; conversely, 5% of bookings outside RACFs were referrals by Ambulance Victoria (ie, non-emergencies). These disparate findings are understandable, as most callers who contacted the MMDS did not have medical training and could not accurately assess the seriousness of the patient’s condition. This interpretation is corroborated by the correspondingly smaller proportions of bookings for people in RACFs that either resulted in an urgent hospital transfer (3%) or were referrals by Ambulance Victoria (< 1%); these bookings were typically made by experienced RACF staff (eg, registered nurses). Alternatively, less experienced RACF staff on duty after hours may contact the MMDS for less serious problems, which would account both for the steeper increase in booking numbers for RACF residents and the lower proportion requiring urgent hospital transfer.

Two-thirds of bookings for people living in RACFs were for women, consistent with the sex ratio of older persons living in non-private dwellings in Australia (69% are women).13 In contrast, 64% of bookings for people living outside RACFs were also for women, slightly higher than the proportion of older women living in the community (about 56%). Difficulties with transport, living alone, personal safety fears, and a reluctance to burden family and friends may partly account for this difference.10,13,21 We also report greater use of the MMDS by people living in areas of higher socio-economic status, which suggests a need to raise awareness of the service among people living in less advantaged areas. This conclusion is supported by an earlier study which reported that people who seek care from an ED could not identify “alternative settings [for seeing] a doctor”.22 It is also consistent with the recommendation by a recent federal review of after-hours care that a pathway for consumers to high quality after-hours advice and support be developed.23 GPs also play a key role in advising patients on the most appropriate after-hours services for their specific needs, which is particularly important for frail and older people living in the general community.

Medical deputising services that arrange home visits by locum GPs overcome some of the barriers to seeking after-hours medical care by older patients, such as transport problems, reluctance to go out at night, and scepticism about telephone advice.10,21 Using these services may also reduce the negative effects of unnecessary ED presentations. The hectic environment of the ED can cause diagnoses and age-related syndromes to be missed in older patients with complex care needs.24 However, despite the overall satisfaction of older patients with medical deputising services,25 barriers to their use still exist, including lack of information about the service, reluctance to see an unfamiliar doctor not acquainted with their medical history, difficulty in obtaining medication after the consultation, and long waiting times.10,25,26

Because of the limited availability of GPs on weekends, older people tended to use the MMDS more frequently on Saturdays and Sundays. Further, peak use of the service was around the beginning of the after-hours period on weekdays and Saturdays. These data suggest that many older people are waiting for the service to open, or they may phone a GP clinic at about closing time and are then referred to a medical deputising service. Our analysis also found that MMDS bookings were lowest late at night (1 am–5 am). This may be because older people fear “being a nuisance”, deterring them from calling during these hours, or that they may prefer to wait to see a familiar doctor.10,20,21 Further qualitative research may provide further insight into the reasons underlying the pattern of use of the MMDS, as would comparing it with that of telephone information services, such as Nurse-On-Call.

As the use of medical deputising services increases, communication between the service and the patients’ usual GPs becomes more important in maintaining the continuity of their care, and particularly for ensuring the efficient handover of clinical information. Indeed, the recent federal review of after-hours care23 recommended that the accreditation of medical deputising services include a requirement for deputising services, and that those who provide after-hours care outside the practice should supply clinical summaries to the patient’s regular practice within 24 hours. Other services, including the nationally shared health record (My Health Record), will also assume greater importance.

Limitations

No distinction was made in our study between RACFs that provided high and low level nursing care, a distinction that applied prior to July 2014. Residents in these two RACF classes are likely to have had different medical needs. Additionally, we did not have any information about the health status of people not living in RACFs; some people, such as those with poorly managed chronic illnesses, may be more likely to require after-hours care. Further, utilisation of MMDS was assessed according to the number of bookings, but this does not distinguish between first-time users and repeat users. Comparing our data with data for telephone information services (eg, Nurse-On-Call) and the ambulance service (which can treat patients on site without transporting them to hospital) would also allow a more complete picture.

As this study is descriptive, it is difficult to impute reasons for some findings. Investigation of the factors associated with increased use of after-hours medical deputising services at critical time points would assist in meeting demand more effectively and improve service delivery. Longitudinal studies that track long term trends could assess the effect of after-hours medical deputising services on the demand for ED services.

Conclusion

Most MMDS bookings led to a locum GP visit, and most bookings were for general practice-type services and did not require a hospital referral. For patients not residing in RACFs, home-visit medical deputising services may be a viable alternative to seeking care from emergency services, as many older people have problems with transport. In 2015, new funding arrangements for providing after-hours services were introduced;27 Primary Health Networks will be charged with supporting locally tailored after-hours services by general practices and a new after-hours GP advice and support line. Nevertheless, medical deputising services remain a critical component of the after-hours landscape in Australia, supplementing the declining numbers of general practices that provide after-hours care. The increasing use of medical deputising services that we have identified will continue to complement telephone helplines and practices that provide their own after-hours care. Policy makers and health practitioners need to ensure that care is integrated and that inappropriate use of these services is not encouraged.

Box 1 –

Areas served by the Melbourne Medical Deputising Service, 2008–2012

Box 2 –

Socio-demographic and other characteristics for 357 112 telephone bookings with the Melbourne Medical Deputising Service for after-hours general practice care for persons aged 70 years or more, by place of residence type, 2008–2012

|

Characteristic

|

Place of residence type

|

P*

|

|

Residential aged care facility

|

Other

|

|

|

Number of bookings

|

290 264

|

66 848

|

|

|

Sex of patient

|

|

|

< 0.001

|

|

Men

|

93 730 (32.8%)

|

23 696 (36.2%)

|

|

|

Women

|

191 708 (67.2%)

|

41 737 (63.8%)

|

|

|

Missing data†

|

4826

|

1415

|

|

|

Mean age of patient (SD), years

|

|

|

|

|

Men

|

84.1 (6.5)

|

81.0 (6.2)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Women

|

86.1 (6.3)

|

81.1 (6.7)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Call was from Ambulance Victoria‡

|

|

|

< 0.001

|

|

Yes

|

324 (0.1%)

|

2704 (5.4%)

|

|

|

No

|

220 039 (99.9%)

|

47 587 (94.6%)

|

|

|

Missing data†

|

69 901

|

16 557

|

|

|

Socio-economic status (quintiles)§

|

|

|

< 0.001

|

|

1 (most disadvantaged)

|

50 312 (17.6%)

|

11 428 (17.9%)

|

|

|

2

|

36 322 (12.7%)

|

6022 (9.4%)

|

|

|

3

|

51 112 (17.9%)

|

13 516 (21.1%)

|

|

|

4

|

66 974 (23.4%)

|

13 709 (21.5%)

|

|

|

5 (least disadvantaged)

|

81 114 (28.4%)

|

19 216 (30.1%)

|

|

|

Missing data†

|

4430

|

2957

|

|

|

Patient’s GP clinic was an MMDS client with arrangements for an MMDS locum GP to provide after-hours care

|

|

|

< 0.001

|

|

Yes

|

239 955 (85.2%)

|

47 762 (76.7%)

|

|

|

No

|

41 632 (14.8%)

|

14 510 (23.3%)

|

|

|

Missing data†

|

8677

|

4576

|

|

|

Outcome of booking

|

|

|

< 0.001

|

|

Patient attended by MMDS locum GP

|

263 706 (90.8%)

|

55 096 (82.4%)

|

|

|

Patient’s usual GP contacted

|

2621 (0.9%)

|

1088 (1.6%)

|

|

|

Request for locum GP cancelled

|

23 937 (8.3%)

|

10 664 (16.0%)

|

|

|

Urgent transfer of patient to hospital organised by MMDS locum GP¶

|

|

|

< 0.001

|

|

Yes

|

8635 (3.3%)

|

3488 (6.3%)

|

|

|

No

|

255 071 (96.7%)

|

51 608 (93.7%)

|

|

|

Missing data†

|

26 558

|

11 752

|

|

|

|

MMDS = Melbourne Medical Deputising Service. SD = standard deviation. * χ2 tests for categorical variables; t tests for continuous variables. † Missing data were omitted from the denominator for percentages and from other calculations. ‡ Data for 2008–2011 only; data for 2012 were not available and comprise the missing data for this attribute. § Socio-economic status groups were generated using the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ SEIFA 2011 Index of Relative Socio-Economic Disadvantage (ranked within Victoria) and the postcode for the usual place of residence of the patient. For individuals living in a residential aged care facility, the postcode of the facility determined the socio-economic status group. ¶ Bookings where the patient was attended by an MMDS locum GP (318 802 people).

|

Box 3 –

Numbers of telephone bookings with the Melbourne Medical Deputising Service for after-hours general practice care for people aged 70 years or more, by type of residence, 2008–2012

Box 4 –

Population rate of telephone bookings with the Melbourne Medical Deputising Service for after-hours general practice care for people aged 70 years or more, by type of residence, 2008–2012

Box 5 –

Telephone bookings with the Melbourne Medical Deputising Service for after-hours general practice care for people aged 70 years or more, 2008–2012, by day of week and type of residence

Box 6 –

Telephone bookings with the Melbourne Medical Deputising Service for an after-hours general practitioner for people aged 70 years or more, 2008–2012, by day of week* and time of day

more_vert

more_vert