One in seven Australians (13.6%) will suffer from back pain on any day,1 which makes this condition the largest contributor to the burden of disease in Australia, according to the Global Burden of Disease Study.2 In Australia, low back pain (LBP) is the most common musculoskeletal condition for which patients consult general practitioners.1 Back problems are more common in older people, and with an ageing Australian population, the 3.7 million GP encounters for LBP in 2012–20131 are likely to escalate. Given this context, GPs need a practical approach to assess and treat their patients with LBP.

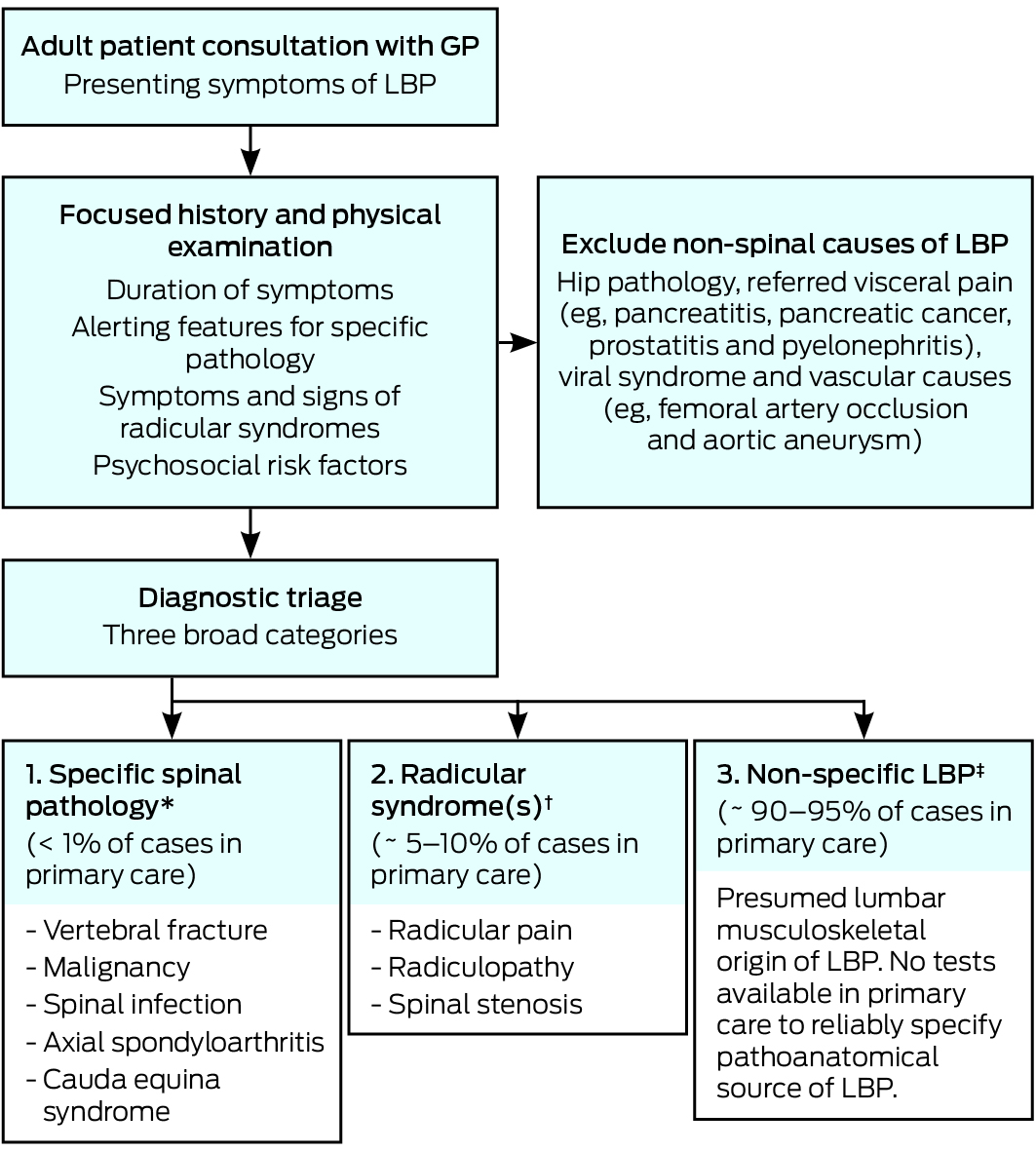

A key step in the primary care management of LBP involves a diagnostic triage that classifies patients into three broad categories (Box 1). Based on a focused clinical assessment, patients are classified as having a specific spinal pathology (< 1%), radicular syndrome3 (ie, nerve root pathology including spinal canal stenosis; ∼ 5–10%), and non-specific LBP ([NSLBP]; 90–95%). The triage approach informs decisions about the need for further diagnostic workup (eg, imaging or laboratory tests), guides the care the GP needs to provide and helps the GP identify the patients who require referral to allied health or medical specialists.4

This article aims to outline the diagnostic triage approach in greater detail than that found in clinical practice guidelines,3–5 and to show the clinical utility of the approach for the primary care management of LBP. We identified relevant current English language clinical guidelines and publications from the Cochrane Library and PubMed in February 2016, our existing records, and citation tracking. We used search terms for LBP and key concepts in our article (eg, differential diagnosis, low back pain, sciatica and spinal stenosis).

Diagnostic triage for primary care management of low back pain

The goal of the diagnostic triage for LBP is to exclude non-spinal causes of LBP and to allocate patients to one of three categories that subsequently direct management (Box 1). A focused history and a physical examination of the patient form the cornerstone to the diagnostic triage classification; moreover, diagnosis of the largest NSLBP group is by exclusion of the other two categories (Box 1).

We describe the approach endorsed in the latest clinical practice guidelines and suggest some updates based on research published subsequent to the guidelines. Limited but essential background information is provided for stepwise application of the diagnostic triage.

Specific spinal pathology

The initial step is to recognise that in primary care, LBP is occasionally the initial symptom of a number of more serious specific spinal pathologies (Box 1), the most common of which is vertebral fracture (Box 2). A range of clinical features or red flags (eg, age > 50 years or presence of night pain) have been proposed to help clinicians identify patients with a higher probability of specific pathology, who require further diagnostic workup to allow a definitive diagnosis. While there are scores of red flags endorsed in texts and guidelines, many are of limited or no value. A good illustration is the red flag “thoracic pain”, which has both a positive and negative likelihood ratio of 1.0 (for cancer), meaning that both a positive and negative test result are uninformative.8 Based on two recent Cochrane reviews, only a small subset of red flags (ie, older age, prolonged corticosteroid use, severe trauma and presence of a contusion or abrasion) are informative for detection of fracture, and a history of malignancy is the only red flag increasing the likelihood of spinal malignancy.8

For patients with suspected specific spinal pathology, the condition itself dictates the next steps the GP should take (Box 2). Patients with rapidly deteriorating neurological status or a presentation suggesting cauda equina syndrome require urgent (same day) referral to a neurosurgeon. Where there is suspicion of infection (such as a spinal epidural abscess that may have important medico-legal implications if missed) or strong suspicion of cancer or fracture, the GP should initiate further diagnostic workup to confirm the diagnosis. When there is less convincing evidence of cancer or fracture, a trial of therapy with review in 1–2 weeks may be considered. In the same way, watchful waiting and a trial of therapy may be appropriate for suspected axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA). However, axSpA is often missed, with most patients typically diagnosed many years after the initial symptoms; therefore, scheduling a review is crucial to avoid this problem. Guidelines for rheumatology referral of axSpA are summarised in Box 2, together with the prevalence, alerting features (ie, risk factors), diagnostic workup and tertiary referral pathways for each of the specific spinal pathologies.

Radicular syndrome

The next step is to recognise, from the focused history and clinical examination, the clinical features that distinguish three subsets of nerve root involvement: radicular pain (sometimes called sciatica), radiculopathy and spinal stenosis (Box 1). Grouped together as radicular syndrome, the source of the clinical features lies in lumbosacral nerve root pathology associated with disc herniations,14 facet joint cysts, osteophytes, spondylolisthesis and acquired or degenerative canal stenosis.15 Severe pathoanatomy, including spinal tumours, may result in deterioration of radicular syndrome and crossover to cauda equina syndrome,16 which demands urgent management (Box 2).

Differential diagnosis is complex. Definitions seldom match the highly variable manifestations seen in clinical practice.17–20 For this reason, distinctive clusters of characteristic history cues and positive clinical examination signs, particularly the neurological assessment, provide a guide to diagnose radicular syndrome and to differentiate the subsets of this category, which is essential for clinical utility of the diagnostic triage (Box 3).

There are three important subsets to consider when diagnosing radicular syndrome:

-

Radicular pain: in primary care, LBP-related leg pain is common with about 60% of patients with LBP reporting pain in the legs;31 however, the subgroup with true radicular pain is much smaller. A prospective cohort study of radicular pain in the Dutch general practice 10-year follow-up20 found that the mean incidence was 9.4 episodes per 1000 person-years. Radicular, neurogenic leg pain, for which there is no gold standard diagnosis,18 is distinct from and more debilitating than somatic referred leg pain, and is associated with greater GP consultations,18 functional limitations, work disability, anxiety, depression and reduced quality of life,32 as well as imaging and surgical health care costs. Cues about the severity, asymmetry and radiating quality of leg pain from the history (Box 3) suggest radicular pain; however, specific dermatomal-dominant pain location has the greatest single-item diagnostic validity.23 Positive nerve tension tests for upper lumbar roots (prone knee bend) or lower roots (straight leg raise and crossed straight leg raise) are common physical examination signs that guide diagnosis.33

-

Radiculopathy: caused by nerve root dysfunction and defined by dermatomal sensory disturbances, weakness of muscles innervated by that nerve root and hypoactive muscle stretch reflex of the same nerve root,22 frequently co-exists with radicular pain. However, a patient with L4 radiculopathy may present with footdrop — which is a severely compromised or absent concentric foot dorsiflexion due to marked weakness of the tibialis anterior muscle, the strongest dorsiflexor of the foot — or paraesthesia without radicular pain, suggesting that the two are separate diagnostic entities. A single positive symptom or sign of sensory (soft) or motor (hard) deficit confirms the diagnosis (Box 3); nevertheless, myotomal weakness is the most diagnostic hard sign.23

-

Spinal stenosis: both degenerative in older patients and acquired or congenital in younger patients. Spinal stenosis has key clinical features such as neurogenic claudication34 relieved in forward flexion or sitting15,35 (Box 3). Neurological examination is often normal36 — in contrast to radicular pain or radiculopathy.

Recent research shows a favourable prognosis for all three radicular syndrome subsets when managed conservatively.18,20,36 Referral to a spinal surgeon should be reserved for patients for whom conservative care has proven insufficient and who have disabling symptoms that have persisted for longer than 6 weeks,37,38 for patients who have severe or progressive neurological deficit, and for patients with cauda equina syndrome.39 A recent trial showing similar outcomes for decompression surgery and conservative management — physiotherapist-delivered education combined with flexion-bias and conditioning exercises — provides support for conservative management of spinal stenosis.36 Another study found no clinically important improvement in symptoms and function after surgery in 57% of patients.40 Moreover, recent research has found no association between magnetic resonance imaging radiological findings and the severity of buttock, leg and back pain, even when analysis was restricted to the level of the spine with the most prominent radiological stenosis.41

Matching primary care treatment for radicular syndrome to the individual patient requires clinical acumen. There is also some uncertainty in management, as there are less clinical trials evaluating radicular syndrome than NSLBP. First line primary care comprising reassurance and advice, pain medication, physiotherapy treatment or rehabilitation (matched to muscle deficits and the reduced envelope of function), and “watchful waiting” would be indicated, for example, for recent onset radicular pain with mild L5 radiculopathy and associated motor deficit of the extensor hallucis longus muscle. This can present as a subtle, audible foot slap noted during gait because the eccentric control of lowering the foot after heelstrike is compromised on the affected side. In contrast to footdrop, foot slap has a relatively minor impact on gait. Second line care may progress to more complex medications, including neuropathic pain medication and oral steroids; however, the efficacy of both interventions is unclear.42–44 Moreover, epidural injections of corticosteroids are considered controversial.45 In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of epidural corticosteroid injections for radiculopathy and spinal stenosis, the researchers concluded that epidural steroid injections for radiculopathy were associated with immediate reductions in pain and improvements in function.11 The benefits, however, were small and not sustained, and there was no effect on long term surgery risk. For spinal stenosis, limited evidence suggested no effectiveness for epidural steroid injections.33

Non-specific low back pain

NSLBP is the third triage group and represents 90–95% of patients with LBP in primary care. It is a diagnosis by exclusion of the first two less prevalent categories (Box 1). In contrast to these categories, there are no identifying features for NSLBP on currently available clinical tests to determine a definitive link between a pain-sensitive structure, such as annulus fibrosus or ligament, and the patient’s pain.27 NSLBP is managed conservatively and no imaging or pathology is recommended.46

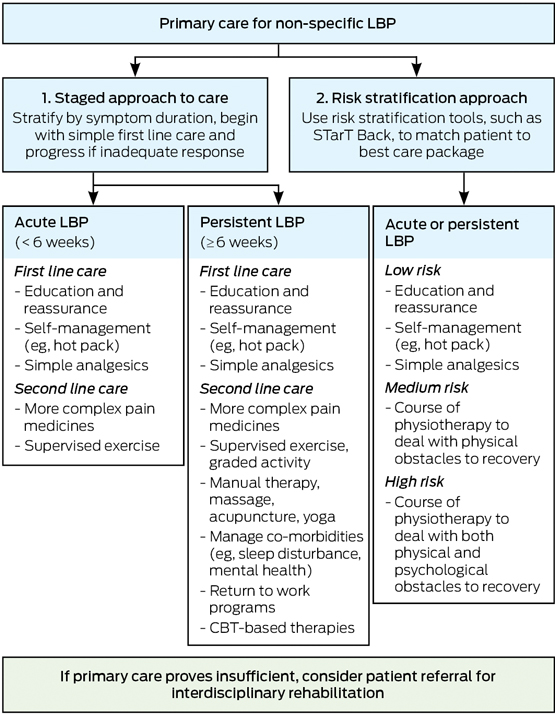

There are two common approaches to staging NSLBP to help direct primary care management (Box 4). The traditional approach was to first stratify by duration of symptoms and then begin with simple care and progress to more complex care if insufficient progress was made. A more recent approach is to use validated risk stratification tools — such as the STarT Back Screening Tool (SBST)47 or the Örebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire48 — to stream patients into different care pathways (Box 4). The SBST is a brief prognostic screener to direct stratified primary care management (Appendix), and which quantifies psychosocial risk for levels of pain, disability and distress as low, medium or high.47 A different treatment package is then matched to the patient depending on their risk category. For example, a low risk category indicates a highly favourable prognosis. Therefore, the matched treatment, aimed at enabling self-management, focuses on dealing with patient concerns and providing information. The medium risk category builds on the low risk package, but adds strategies to improve primary outcomes of pain and function (including work) and to minimise disability (even if pain is unchanged). For high risk scores, matched treatment builds on both the low and medium packages, but additionally includes psychologically informed physiotherapy, provided by a physiotherapist trained in cognitive behavioural therapy (Box 4).

For all patients — to reduce symptoms, activity limitation and participation restriction — management should be guided by a biopsychosocial understanding of LBP, targeting biological, psychological and social contributors to the condition.49 Biological components may be addressed with exercise and ergonomic education (eg, a standing desk to avoid prolonged sitting), whereas psychological therapies and modifications or pacing within sporting participation may be necessary to deal with the psychosocial components of LBP. The recognition that problems — other than the pain intensity — may need to be managed is important in the biopsychosocial model of LBP. Key examples would be the distress and disability associated with LBP; comorbidities, such as sleep disturbance or depression; and disruptions to the patient’s normal work and social roles. The general practice management of NSLBP will thus vary to reflect the clinical presentation of the individual patient. For example, an uncomplicated acute episode may only require education, reassurance and simple pain medicines, whereas a patient with chronic LBP that is persistently debilitating may require complex pain medicines, assessment of psychosocial risk factors, mental health screening and referral for cognitive behavioural therapy (Box 4). For some patients, it would be best practice for the GP to use a chronic disease management plan to manage the patient in a team care arrangement with two other health professionals, such as a rheumatologist, physiotherapist, dietitian50 or psychologist. Management in an intensive interdisciplinary rehabilitation program may be considered for patients who do not respond to primary care management, or where the initial presentation reveals many complex barriers to recovery.

The use of the terms “ordinary backache”51 or “mechanical back pain” has advantages, as the term “non-specific low back pain” may not engender patient confidence in the GP to identify a reason for their pain. The diagnostic triage can guide patient education: “ordinary backache” is extremely common (90–95%), and the patient’s clinical assessment has not revealed any evidence of specific pathology (< 1%) or spinal nerve involvement (5–10%; Box 1). Using the triage in this way removes “pain” from NSLBP nomenclature, and potentially minimises imaging requests and catastrophising. Education of patients on evidence around LBP is important to dispel myths and counter anxious or demanding requests for unwarranted imaging, which can often reveal incidental findings. Radiological signs of disc wear and tear (eg, degeneration [91%], bulges [56%], protrusion [32%] and annular tears [38%]) are common in pain-free patients.52 It is also worth noting that the radiation level of a lumbar spine computed tomography scan is equivalent to that of 300 chest x-rays.53 Reassurance that LBP settles and responds well to staying active, together with advice regarding simple safe symptom control (eg, heat or analgesia), continuing normal daily activities and staying at work (with modification if needed) foster appropriate patient attitude and self-management.46

In summary, most patients presenting to primary care with LBP do not require imaging or laboratory tests, and a focused clinical assessment is sufficient to direct management. Part of the consultation should be used to gauge the patient’s understanding of their back pain, so that GPs are better equipped to provide relevant education and advice to their patient. This important aspect of care, ensuring that patients are active participants in their recovery from LBP, has been well described in a recent article.54

Conclusion

Back pain, like headache, is a symptom requiring differential diagnosis. Diagnostic triage, based on a focused history and physical examination, anchors LBP diagnosis in primary care. It guides the GP to triage each patient into one of three LBP categories. Specific spinal pathology and radicular syndrome are the two distinct LBP triage categories that need to be excluded before a diagnosis of NSLBP, or ordinary backache, can be made for most patients.

In this article, we have outlined a practical approach for a stepwise application of diagnostic triage in primary care. Accuracy in the initial LBP triage category requires clinical acumen and strongly affects subsequent clinical decision making. Therefore, clinically relevant diagnostic pointers, together with recent research evidence across the three domains, have been synthesised to sharpen diagnosis of the three categories and to guide subsequent clinical pathways in primary care.

The first imperative is prompt identification and referral of specific spinal pathology. The second is to identify and appropriately manage the wide clinical variability within patients presenting with radicular syndrome, that is, radicular pain, radiculopathy and lumbar spinal stenosis. Collaborative conservative care and evidence-based referral for imaging and spinal surgery are important for this group of patients. Third, the triage process equips GPs to confidently educate and reassure 90–95% of patients with LBP that there is no evidence of specific pathology or nerve root involvement. This paves the way for a biopsychosocial model of care for patients presenting with NSLBP: to manage pain intensity, but also to quantify risk for disability so that patients can be directed to appropriate pathways of care.

Diagnostic triage of LBP empowers GPs in their role as gatekeepers of LBP in primary care. Practical application of this tool is essential to anchor LBP diagnosis in primary care and to deal with the complexity of a presenting symptom that is vexing, costly and too prevalent to be ignored.

Box 1 –

Diagnostic triage for low back pain (LBP)

Box 2 –

Specific spinal pathologies presenting in primary care

|

|

Prevalence in primary care

|

Alerting features

|

Diagnostic workup

|

Tertiary referral

|

|

|

Vertebral fracture

|

1.8–4.3%6

|

Older age (> 65 years for men, > 75 years for women)7

Prolonged corticosteroid use

Severe trauma

Presence of contusion or abrasion

|

Imaging:

- immediate (for major risk);

- delay (for minor risk, 1-month “watch and wait” trial); and

- laboratory test: ESR7

|

Spine surgeon

|

|

Malignancy

|

0.2%8

|

History of malignancy*

Strong clinical suspicion

Unexplained weight loss, > 50 years (weaker risk factors)

|

Imaging:

- immediate (for major risk);

- delay (for minor risk); and

- laboratory test: ESR7

|

Oncologist

|

|

Spinal infection

|

0.01%9

|

Fever or chills

Immune compromised patient

Pain at rest or at night

IV drug user

Recent injury, dental or spine procedure

|

Imaging:

- immediate (MRI); and

- laboratory tests: CBC, ESR, CRP10

|

Infectious diseases specialist

|

|

Axial spondyloarthritis11

|

0.1–1.4%12,13

|

Chronic back pain (> 3 months’ duration), with back pain onset before 45 years of age and one or more of the following:

- inflammatory back pain (at least four of: age at onset 40 years or younger, insidious onset, improvement with exercise, no improvement with rest, and pain at night — with improvement when getting up);

- peripheral manifestations (in particular arthritis, enthesitis or dactylitis);

- extra-articular manifestation (psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease or uveitis);

- positive family history of spondyloarthritis; and

- good response to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

|

Refer to rheumatologist if strong suspicion of axial spondyloarthritis

|

Rheumatologist (where a rheumatologist is not available, consider another medical specialist with expertise in musculoskeletal conditions)

|

|

Cauda equina syndrome

|

0.04%9

|

New bowel or bladder dysfunction

Perineal numbness or saddle anaesthesia

Persistent or progressive lower motor neuron changes

|

Imaging: immediate MRI

|

Spine surgeon

|

|

|

CBC = complete blood count. CRP = C-reactive protein. ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate. IV = intravenous. MRI = magnetic resonance imaging. * A history of malignancy is the only proven single alerting feature (red flag) for suspected malignancy.8

|

Box 3 –

Differential diagnosis of radicular syndrome: key clinical features of three subsets*

|

Condition

|

History

|

Physical examination

|

|

|

Radicular pain†

|

Leg pain typically worse than back pain18,21

Leg pain quality — sharp, lancinating or deep ache increasing with cough, sneeze or strain22

Leg pain location — unilateral, dermatomal concentration (below knee for L4, L5, S1)23,24

|

Positive provocative tests for dural irritation: straight leg raise (L4, L5, S1, S2) and prone knee bend (L2, L3, L4)14,25

Lumbar extension and ipsilateral side flexion may exacerbate radicular pain (Kemp sign)

Sometimes accompanying radiculopathy signs

|

|

Radiculopathy‡

|

Numbness or paraesthesia (typically in distal dermatome)26

Weakness or loss of function (eg, footdrop)22,27

|

Sensory: diminished light touch or pinprick in dermatomal distribution,27 paraesthesia intensifies with lumbar extension

Motor: myotomal weakness27

Reflexes: reduced or absent knee jerk or ankle jerk14,25

|

|

Lumbar spinal stenosis§

|

Neurogenic claudication limiting walking tolerance15,28

Older patient, bilateral leg pain or cramping with or without LBP15,29

Bilateral leg pain exacerbated by extended posture (eg, standing)30 and relieved by flexion (eg, sitting, bending forward and recumbent posture)15

|

Normal neurological assessment during rest (sometimes mild motor weakness or sensory changes)29

Antalgic postures (stooped standing and walking), straightened posture can amplify leg pain or numbness28

Wide based gait28

|

|

|

LBP = low back pain. * Radicular pain and radiculopathy frequently coexist.19 † Radicular pain is caused by nerve root irritation and there is a focus on symptom-related eligibility criteria from the history.22 Because of dermatomal overlap, pain radiation is a more reliable guide than sensory loss for localising the root involvement.27‡ Radiculopathy is due to nerve root compromise; therefore, there is a focus on sign-related eligibility criteria from the physical examination.22 § Lumbar spinal stenosis is a clinical diagnosis where neurogenic claudication is the cardinal diagnostic symptom from the history.15 Neurogenic claudication is defined as the progressive onset of pain, numbness, weakness and tingling in the low back, buttocks and legs, which is initiated by standing, walking or lumbar extension.15 Imaging to determine structural pathology is reserved for when surgery is being considered.15

|

Box 4 –

Primary care management of non-specific low back pain (LBP)

more_vert

more_vert