The known Managing risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) in patients with diabetes improves their outcomes, but many are not prescribed the recommended treatments. Electronic decision support is a scalable strategy for improving guideline implementation.

The new The implementation of recommended management of CVD risk factors in people with diabetes is incomplete, but better than for patients without diabetes. An electronic decision support tool achieved modest improvements in CVD risk factor screening and treatment escalation in patients with diabetes.

The implications While computerised tools may play an important enabling role, broader strategies are needed to close evidence–practice gaps.

By 2030, diabetes may affect more than 300 million people worldwide.1 Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the primary cause of mortality and morbidity in patients with type 2 diabetes,2 and large studies have found that managing risk factors for CVD in patients with diabetes reduces both.3,4 According to risk management guidelines, decisions about the need for and the intensity of intervention should be based on the estimated absolute risk.5

A number of guidelines for managing CVD risk in people with diabetes have been published, but studies in Australia6,7 and overseas8–10 have consistently found that these strategies have been only incompletely implemented. Most Australian studies, however, predate a number of targeted quality improvement (QI) programs, including the National Divisions Diabetes, Australian Primary Care Collaboratives, and National Integrated Diabetes Programs, as well as the introduction of targeted incentive payments to general practitioners and practices, and may therefore not accurately reflect current practice. Whether any of these initiatives improved quality of care is unknown.

In this article we describe the contemporary primary care management in Australia of patients with diabetes participating in a study of CVD risk management in primary health care. Our primary objectives were to assess adherence to CVD risk screening and management guidelines, and to determine the effectiveness of a new QI intervention for improving risk management. The main results of the QI study have been published elsewhere;11 we report here a subgroup analysis comparing the outcomes for patients with and without diabetes.

Methods

The Treatment of Cardiovascular Risk in Primary care using Electronic Decision Support (TORPEDO) study was a parallel arm, cluster randomised, controlled trial involving 60 Australian primary health care services (40 general practices and 20 Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services [ACCHSs]). It assessed whether a QI intervention combining point-of-care electronic decision support with audit and feedback tools improved CVD risk management. The TORPEDO study methods have been described in detail elsewhere.11

Practice eligibility criteria

Health services were eligible to participate if they exclusively used either of the two most common electronic health record systems in Australia for recording risk factor information, pathology test results and prescribed medications. General practices from the Sydney region were recruited between September 2011 and May 2012 through primary health care networks (previously: Medicare Locals), and ACCHSs through two state representative bodies in New South Wales and Queensland.

Patient eligibility criteria

Eligible patients were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people at least 35 years old and non-Indigenous people at least 45 years old (age ranges based on national CVD risk guidelines5) who had attended a participating service at least three times during the preceding 24 months and at least once during the past 6 months. The presence or absence of diabetes was established by a recorded diagnosis of diabetes (type not specified) or a glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) measurement at baseline of more than 53 mmol/mol. This threshold was chosen as a conservative estimate during the transition period in Australian diagnostic criteria for diabetes, which now recommend a threshold of 48 mmol/mol.

Randomisation

Services were randomised (1:1) to intervention or control groups, stratified at three levels: ACCHSs v mainstream general practices; service size (less than 500 v 500 or more eligible patients); and current participation in a national or state QI program. Permuted block randomisation was performed centrally; outcome analyses were blinded to allocation.

Intervention

Full details of the intervention have been published previously.12 In brief, a screening and management algorithm was developed and validated, based on a synthesis of recommendations from several guidelines (online Appendix 1).13 The algorithm incorporated CVD risk assessment, as well as recommendations for managing CVD, chronic kidney disease, blood pressure (BP) and cholesterol, but not for blood glucose management.

Five-year risk of a cardiovascular event was estimated with the Australian risk calculator, based on the 1991 Anderson Framingham equation.14 High CVD risk is defined in Australian guidelines5 as a calculated 5-year CVD risk of greater than 15%; the presence of diabetes in a person over 60 years old, diabetes together with albuminuria, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) below 45 mL/min/1.73 m2, systolic BP greater than 180 mmHg, diastolic BP greater than 110 mmHg, or total blood cholesterol level over 7.5 mmol/L; or the presence of CVD, defined as a recorded diagnosis of coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease (ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack), or peripheral vascular disease. Risk was based on the most recent available results, whether or not the participant was being treated for that risk factor.

The algorithm interfaced directly with the two eligible electronic records systems. Data from the patient record were automatically prepopulated in the tool, and used to generate point-of-care CVD risk management recommendations. A data extraction tool provided site-specific audits, and feedback performance reports were generated. Clinical staff were trained in the application of the tool and had access to a support desk and bi-monthly webinars. The intervention lasted a minimum of 12 months.

Data collection

De-identified data for all patients who met the eligibility criteria were extracted from the clinical database of each health service with a validated data extraction tool.15 The extracts were uploaded to the study database together with an encrypted identifier code.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes for the randomised trial11 were:

-

The proportion of eligible patients who received appropriate screening for CVD risk factors by the end of the study. This was defined as data for all relevant risk factors having been recorded or updated (smoking status, BP in the past 12 months, total blood cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol levels in the past 24 months).

-

The proportion of patients at high CVD risk at baseline who were receiving recommended medication prescriptions at the end of the study (prescription of at least one BP-lowering drug and a statin for people at high risk without CVD; reduction of CVD risk to below 15% by the end of study; prescription of at least one BP-lowering drug together with a statin and an antiplatelet agent for people with established CVD, unless contraindicated by oral anticoagulant use).

Secondary outcomes included:

-

the primary outcomes for individuals at high risk who were undertreated at baseline;

-

measurements of individual CVD risk factors (smoking status, BP, blood lipid levels, body mass index [BMI], eGFR, albuminuria);

-

escalation of drug prescription for patients at high risk of CVD (either newly prescribed or additional antiplatelet, BP-lowering and lipid-lowering agents); and

-

BP and serum lipid levels in people at high risk of CVD.

Sample size

Randomisation of 60 services (30 per arm) would provide 90% power to detect an absolute higher occurrence of 10% for each primary study outcome in the intervention arm, assuming a 10% absolute improvement in the control arm, an average cluster size of 750 patients (30% of whom were at high risk of CVD), baseline risk factor measurement and prescribing rates of 50%, α = 0.05 (two-sided), and an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.05.

Statistical analysis

Post hoc descriptive analyses of baseline data from the TORPEDO study and of data for the cohort of participants present at both baseline and study end were undertaken. Data are presented as means with standard deviations, medians with interquartile ranges, or proportions. Baseline differences between patients with and without diabetes were tested in generalised estimating equations (GEEs) with an exchangeable correlation structure to account for clustering of patients in services.

To determine the predictors of suboptimal drug therapy at baseline, cross-sectional analyses were conducted in a GEE model with logit link function, including both patient level characteristics and service level data. Associations between risk factors and drug therapy were expressed as unadjusted odds ratios (with 95% confidence intervals [CIs]) for binary outcomes.

Intervention effects were analysed by log-binomial GEE regression. The rate ratios of intervention effect were calculated for the individual outcomes at the end of the study. The effects of the intervention in the subgroup of undertreated participants at baseline were analysed in the same model, stratified by diabetes status. An interaction term was included in all models to assess heterogeneity of effects by diabetes status.

Statistical analyses were conducted in SAS Enterprise Guide 5.1 (SAS Institute).

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) (reference, 2012/2183) and the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of New South Wales HREC (reference, 778/11). Signed agreements with participating sites were obtained. Individual consent waiver was granted because data were collected from de-identified extracts from the electronic health record system.

Results

Recruitment

Sixty-four services were initially recruited; 31 were randomised to the intervention arm (but one withdrew shortly after randomisation) and 30 to usual care (online Appendix 2). Baseline data were extracted for 53 164 patients, including 8829 with diabetes; a cohort of 38 725 (6909 with diabetes) were followed up for outcome evaluation. The median follow-up time was 17 months.

Sample characteristics at baseline

Of the 8829 patients with diabetes at baseline, most had a recorded diagnosis of diabetes (97%); 3% were defined by HbA1c levels exceeding 53 mmol/mol. The mean age, and the proportions who were men, smokers or Indigenous Australians were higher for people who had diabetes than for those who did not. Their mean systolic BP and blood triglyceride levels were also higher, while their low-density lipoprotein (LDL)- and HDL-cholesterol levels were lower. Albuminuria, renal impairment and an established diagnosis of CVD were more common in people with diabetes (for all differences: P < 0.001; online Appendix 3).

Recording of risk factors and CVD risk at baseline for people with diabetes

Overall, appropriate measurement of CVD risk factors in people with diabetes was greater than for those without diabetes (62.0% v 39.5%; P < 0.001; online Appendix 3), a difference that remained after adjusting for age, sex, and Indigenous status (P < 0.001). BMI was recorded for 81% of people with diabetes, smoking status for 89%, HbA1c levels for 86%, systolic BP for 94%, albuminuria assessment for 59%, and eGFR for 87%. Recording rates for total, LDL- and HDL-cholesterol levels were 87%, 82% and 79% respectively.

More than one-quarter of patients with diabetes (26%) had established CVD; a further 12%, 4%, and 49% had an estimated 5-year CVD risk that was low (< 10%), medium (10–15%), or high (> 15% or clinically high risk condition present) respectively. There was insufficient information for 825 patients (9%) to categorise their risk (online Appendix 3).

Prescribing rates at baseline for people with diabetes at high risk of CVD

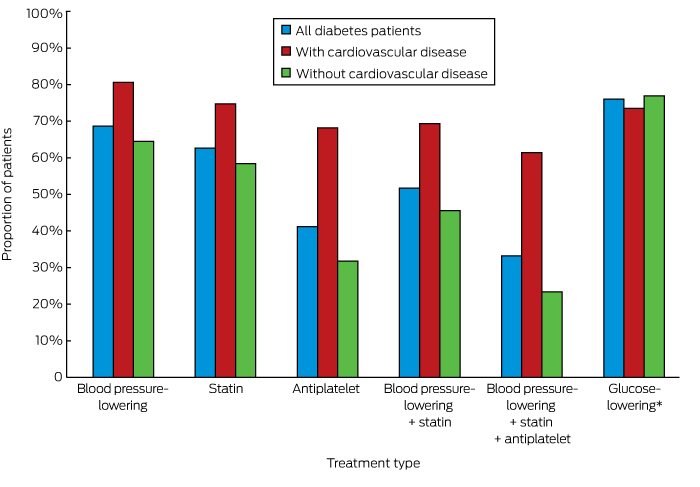

Appropriate prescribing of medications for those identified as being at high risk of CVD was greater among people with diabetes than for those without diabetes (55.5% v 39.6%, P < 0.001; online Appendix 3). Overall, 52.4% of people with diabetes at high risk of CVD but without established CVD and 61.4% of patients with diabetes and established CVD were prescribed recommended medications for averting CVD; the corresponding figures for people without diabetes were lower (22.0% and 49.3% respectively; for each comparison, P < 0.001) (online Appendix 3). The individual medication types prescribed for people with diabetes are shown in Box 1.

Risk factor targets

The HbA1c levels of 57.3% of patients with diabetes exceeded 53 mmol/mol; about one-quarter of these patients were not prescribed glucose-lowering therapy (Box 2). Similarly, the BP and lipid levels of large proportions of patients with diabetes exceeded recommended target levels (online Appendix 4); of the 61.9% of patients who did not meet the LDL-cholesterol target of 2.0 mmol/L, 44.3% were not prescribed a statin (Box 2).

Predictors of drug prescription

People with diabetes who were older (P < 0.001) or Indigenous (P = 0.030), or had a higher HbA1c level (P = 0.030), higher systolic BP (P < 0.001), or albuminuria (P < 0.001), were more likely to be prescribed the recommended combination treatment. Conversely, those with higher total cholesterol levels were less likely to receive optimal combination treatment (P < 0.001). Those who did not have a government-reimbursed health assessment (P = 0.012) or care plan (P < 0.001) were also less likely to be prescribed the recommended medications. Service type (general practice v ACCHS) did not influence drug prescription in univariable or multivariable analyses (online Appendix 5).

Effectiveness of the QI intervention

The baseline characteristics of the cohort used for outcome evaluation were similar for the intervention and control groups (online Appendix 3). The intervention was less effective in improving risk factor screening in patients with diabetes than in those without diabetes (P = 0.01). The intervention was only effective in improving rates of prescribing of recommended medications for undertreated individuals at high risk. and was not influenced by diabetes status (P = 0.28). The intervention was associated with intensification of existing antiplatelet, lipid-lowering, and BP-lowering therapy to a similar extent in people with and without diabetes. The intervention did not affect the prescription of glucose-lowering therapy (Box 3).

Discussion

People with diabetes in a contemporary Australian primary care population were more likely to be screened and prescribed the recommended medications for managing CVD risk factors than those without diabetes. The QI intervention was modestly effective in improving screening and treatment levels, but the evidence–practice gaps remained substantial.

Screening deficits were most marked with regard to cholesterol and albuminuria tests, consistent with both overseas16 and local17,18 reports. A recent French study16 found that only half of a group of patients with diabetes had been screened for proteinuria or albuminuria during the previous 12 months, suggesting that renal function is a poorly assessed CVD risk factor. Underprescribing of recommended treatments was striking when the patients with diabetes in our study were stratified by absolute risk: 39% of those with established CVD and 48% of those at high risk of CVD were not prescribed the recommended treatments; almost half of those with diabetes and LDL-cholesterol levels above 2.0 mmol/L were not receiving statin therapy. Similarly, BP targets were not met by half the patients with diabetes, of whom more than one-quarter were not prescribed antihypertensive therapy. These treatment deficits are consistent with international experience,8–10,16 and reflect modest improvements when compared with the findings of previous Australian studies of lipid6,7 and BP7,19 management.

About one-half of people with diabetes did not meet the recommended HbA1c goal of 53 mmol/mol or less, similar to the 57% figure in the 2003/2004 assessment of the United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) participants.20 It is worrying that about one-quarter of our patients with HbA1c levels over 69 mmol/mol were not prescribed glucose-lowering medication, a proportion substantially larger than the 3% of patients with HbA1c levels of 53 mmol/mol or more not treated in a recent Canadian study.10 Our findings may be partly explained by patient preference for non-pharmacological treatment, and by relaxed glycaemic targets in certain populations (older people, and people with frequent hypoglycaemia or hypoglycaemic unawareness).

Our findings suggest that undertreatment has diminished to some degree since 2002, which may reflect the effect of incentive schemes and quality of care initiatives. The deficits that remain may be explained by the proliferation of guidelines with differing perspectives, and time-pressured consultations with patients presenting with several complaints. Patients with diabetes who had a formal care plan, enabling coordination of their management with other health care providers, were more likely to be treated as recommended. However, causal inferences cannot be made, as numerous factors may confound this association.

The finding that CVD risk screening and management at baseline was better for those with diabetes than for people without diabetes is consistent with other reports,21,22 and may explain why the effect of the intervention was less marked in these patients. Although it was not effective in improving the overall level of new prescriptions for individuals at higher risk of CVD, the intervention was associated with improvements for people who were not receiving recommended treatments at baseline, regardless of their diabetes status. This is important in light of suggestions that therapeutic inertia may be a greater contributor to lost therapeutic benefit in patients with diabetes than lack of treatment.23

There is evidence that patient-directed interventions combined with physician-focused strategies may be more effective than the latter alone.24 Successful elements of collaborative care programs for improving chronic disease management include evidence-based guidelines, systematic screening and monitoring of risk factors, scheduled recall visits, new or adjusted roles for team members, information support for the clinician, enhanced self-management by the patient, effective communication between all members of the care team, and audit information for the practice.25 New policy proposals, such as “Health Care Homes”,26 and a renewed focus on initiatives such as “My Health Record” incorporate some of these elements.

Study limitations

Many of the sites in our study were teaching practices; this may explain why performance was higher than reported in previous studies. However, the recruited services were reasonably representative of Australian general practice with respect to the use of information technology.27 The ACCHSs recruited were geographically diverse and had similar service characteristics to the sector as a whole.28

The National Vascular Disease Prevention Alliance (NVDPA) guidelines5 recommend incorporating pre-treatment risk factor levels when assessing CVD risk. As pre-treatment data were not available, we analysed the patients’ most recent BP and lipid data, regardless of treatment status, and this may have led to underestimating risk for some individuals. However, as 72% of patients with diabetes were at high risk regardless of their risk score (online Appendix 3), this was probably not a major problem.

We regarded 2 years as an appropriate interval between lipid measurements, rather than varying the interval according to risk status as recommended by NVDPA guidelines. This may not have been appropriate for individuals at high risk, for whom more frequent testing is recommended. Conversely, the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners guidelines recommend 5-yearly lipid measurements for people at low risk;29 if doctors are adhering to these recommendations, the frequency of assessment may be adequate, but with a median follow-up period of 17 months we were not able to assess whether this was the case. If biases were introduced by using different lipid measurement intervals, we would expect them to be the same for the intervention and control arms.

Other limitations included the fact that that the type of diabetes was not specified, and that relying on electronic records data precluded assessing the role of clinical judgement in treatment decisions.

Conclusion

Although recommendations for managing CVD risk were more frequently implemented for people with diabetes than for those without diabetes, evidence–practice gaps remain. While the evaluated intervention was moderately effective in improving screening of risk factors, additional strategies are needed if Australia is to meet targets of reducing mortality for CVD and diabetes by 25% over the next 10 years.30

Box 1 –

Rates of prescribing of currently recommended cardiovascular disease risk-factor-specific medications for patients with diabetes

Box 2 –

Patients with diabetes with values above targets at baseline, and number who did not receive the corresponding recommended treatment

|

|

Patients with elevated level

|

Number not treated to reduce level

|

|

|

HbA1c level

|

|

|

|

> 53 mmol/mol

|

4329 of 7556 (57.3%)

|

1038 (24.0%)

|

|

> 69 mmol/mol

|

1822 of 7556 (24.1%)

|

450 (24.7%)

|

|

Blood pressure (BP)

|

|

|

|

Systolic BP > 130 mmHg or diastolic BP > 80 mmHg

|

4835 of 8329 (58.1%)

|

1354 (28.0%)

|

|

LDL-cholesterol level

|

|

|

|

> 2.0 mmol/L

|

4339 of 7007 (61.9%)

|

1922 (44.3%)

|

|

> 2.5 mmol/L

|

2769 of 7007 (39.5%)

|

1412 (51.0%)

|

|

|

HbA1c = glycated haemoglobin; LDL = low-density lipoprotein.

|

Box 3 –

Effects of the quality improvement intervention in patients with and without diabetes

|

|

Intervention

|

Usual care

|

Rate ratio

|

95% CI

|

P*

|

|

|

Receiving appropriate screening

|

12 164/19 385 (62.8%)

|

10 317/19 340 (53.4%)

|

1.25

|

(1.04–1.50)

|

0.01

|

|

With diabetes

|

2738/3617 (75.7%)

|

2323/3292 (70.6%)

|

1.14

|

(1.00–1.30)

|

|

|

Without diabetes

|

9426/15 768 (59.8%)

|

7994/16 048 (49.8%)

|

1.28

|

(1.04–1.58)

|

|

|

Receiving appropriate screening (undertreated at baseline)

|

3773/9276 (40.7%)

|

3532/10 782 (32.8%)

|

1.38

|

(1.10–1.73)

|

< 0.01

|

|

With diabetes

|

559/1160 (48.2%)

|

507/1151 (44.0%)

|

1.28

|

(1.00–1.63)

|

|

|

Without diabetes

|

3214/8116 (39.6%)

|

3025/9631 (31.4%)

|

1.40

|

(1.11–1.78)

|

|

|

Patients at high risk of cardiovascular disease

|

|

Receiving appropriate prescriptions

|

3030/5335 (56.8%)

|

2483/4846 (51.2%)

|

1.11

|

(0.97–1.27)

|

0.10

|

|

With diabetes

|

1700/2679 (63.5%)

|

1458/2495 (58.4%)

|

1.06

|

(0.93–1.21)

|

|

|

Without diabetes

|

1330/2656 (50.1%)

|

1025/2351 (43.6%)

|

1.18

|

(1.03–1.36)

|

|

|

Receiving appropriate prescriptions (undertreated at baseline)

|

1085/2827 (38.4%)

|

472/2263 (20.9%)

|

1.59

|

(1.19–2.13)

|

0.28

|

|

With diabetes

|

553/1269 (43.6%)

|

178/923 (19.3%)

|

1.63

|

(1.11–2.38)

|

|

|

Without diabetes

|

532/1558 (34.2%)

|

294/1340 (21.9%)

|

1.53

|

(1.16–2.01)

|

|

|

Increased antiplatelet therapy†

|

470/2638 (17.8%)

|

65/2424 (2.7%)

|

4.79

|

(2.47–9.29)

|

0.08

|

|

With diabetes

|

210/908 (23.1%)

|

20/829 (2.4%)

|

7.28

|

(3.34–15.9)

|

|

|

Without diabetes

|

260/1730 (15.0%)

|

45/1595 (2.8%)

|

4.05

|

(2.03–8.08)

|

|

|

Increased lipid-lowering therapy†

|

1026/5335 (19.2%)

|

226/4846 (4.7%)

|

3.22

|

(1.77–5.88)

|

0.84

|

|

With diabetes

|

608/2679 (22.7%)

|

130/2495 (5.2%)

|

3.32

|

(1.74–6.33)

|

|

|

Without diabetes

|

418/2656 (15.7%)

|

96/2351 (4.1%)

|

3.22

|

(1.77–5.86)

|

|

|

Increased blood pressure-lowering therapy†

|

1243/5335 (23.3%)

|

586/4846 (12.1%)

|

1.89

|

(1.09–3.28)

|

0.54

|

|

With diabetes

|

729/2679 (27.2%)

|

316/2495 (12.7%)

|

1.91

|

(1.09–3.35)

|

|

|

Without diabetes

|

514/2656 (19.4%)

|

270/2351 (11.5%)

|

1.96

|

(1.10–3.47)

|

|

|

Patients with HbA1clevels > 53 mmol/mol at baseline

|

|

Appropriate glucose-lowering drug

|

1111/1269 (87.6%)

|

955/1118 (85.4%)

|

1.02

|

(0.95–1.11)

|

|

|

Increased glucose-lowering therapy

|

711/2679 (26.5%)

|

304/2495 (12.2%)

|

1.75

|

(0.95–3.22)

|

|

|

|

* Patients with diabetes v patients without diabetes. † For patients not meeting recommended targets for corresponding parameters (online Appendix 4).

|

more_vert

more_vert