Case record

An 8-year-old girl had received treatment for scabies at a health centre in a remote Northern Territory Arnhem Land community on 32 occasions since her birth. Seventeen of these occasions required treatment with parenteral antibiotics for secondary infection. Many episodes were noted to involve the “whole body” and on two occasions she had required hospitalisation. During this time, she was also found to have a low body mass index and failure to thrive.

The girl was often found crying from pain and itch and had been excluded from school for extended periods because of her infectivity. Her family reported that she was bullied by her peers because of the disfigurement of her skin. Her frequent bouts of disfiguring scabies, skin sores and weight loss had led to referrals to child and family services over concerns of parental neglect.

The girl was brought to the attention of East Arnhem Scabies Control Program staff in 2011. Contact tracing was initiated, and a senior member of the family, with whom the girl shared a room, was found to have Grade 2 (moderate) crusted scabies. Clinical audits showed that the senior family member had repeatedly presented with crusted scabies since 1996. After a hospital admission in 2006, she had avoided contact with health services, even though her skin condition deteriorated, reportedly due to fear of the treatment regimen involving extended isolation in hospital and the use of creams that caused a burning skin sensation.

The senior family member was subsequently treated for crusted scabies and the girl and other household members were treated for simple scabies. The woman was then enrolled in a pilot program to prevent recurrent disease. During 19 months of follow-up with the preventive regimen in place for the woman, the girl’s skin condition improved and required no further specific management other than treatment for scabies on one occasion.

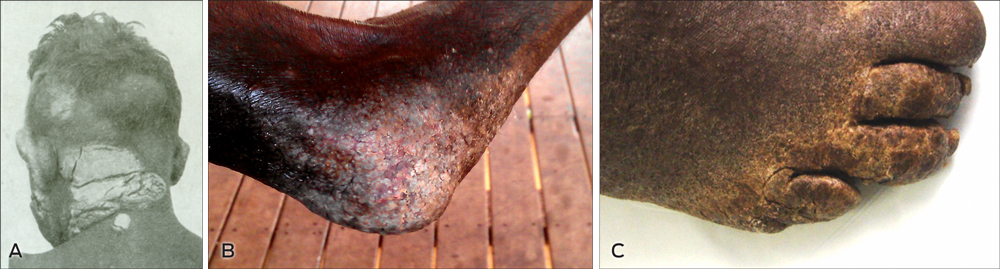

Crusted scabies is a highly infectious, debilitating and disfiguring condition (Box 1) that develops when scabies mite proliferation is not controlled by the host immune system. It is characterised by hyperkeratotic skin crusts and mite loads of a million or more on affected individuals (up to 4700 mites per gram of skin), compared with a total of 10–15 mites in simple scabies.2 Crusted scabies is generally seen in immunocompromised patients3 and historically had a 5-year mortality rate of up to 50%.4 However, a multidose regimen of ivermectin, benzyl benzoate and keratolytic agents introduced in 1996 at the Northern Territory’s Royal Darwin Hospital has led to a significant decrease in the annual mortality rate, to 1.6%.4 Unmanaged crusted scabies is known to cause outbreaks of simple scabies and contributes to the hyperendemic rates seen in many remote communities.4,5

While rare in urban settings, rates of crusted scabies reported in remote Aboriginal communities of northern Australia are the highest in the world.4,6 A review of 78 patients admitted to hospital for crusted scabies in northern Australia over 10 years found nearly all (97%) were Aboriginal people from remote communities, and in nearly half of these patients no underlying immune defect was found.4 From its inception in early 2011 to April 2014, active case finding by the East Arnhem Scabies Control Program (EASCP) across 11 remote communities of northern Australia and their homelands had confirmed 20 cases (1.8 cases per 1000 population).

There is currently no register or follow-up of people living in scabies-endemic areas who are at risk of developing recurrent crusted scabies. Recurrences are only detected if patients self-present to health services and are seen by a clinician familiar with the condition. Current protocols treat the condition acutely. The EASCP postulated that the lack of follow-up surveillance and chemoprophylaxis was inadequate for patients returning to endemic areas.

Here, we present results of routine monitoring and evaluation of the EASCP between August 2011 and June 2013, from the three remote East Arnhem communities in the NT where we had data sharing agreements to access clinical records and the operational capacity to deploy a preventive program. Individual consent was obtained to publish case history details. Publication of EASCP monitoring data was approved by the board of Miwatj Health Aboriginal Corporation and the Human Research Ethics Committee of the NT Department of Health and Menzies School of Health Research (approval number 2013-2055).

The East Arnhem Scabies Control Program

The EASCP was established in early 2011 and is a joint initiative of One Disease, Miwatj Health Aboriginal Corporation and the NT Government Department of Health. The consultancy EveryVoiceCounts was contracted to design the program and guide implementation. More information on the EveryVoiceCounts learning partnership model used to design the program is available at http://www.everyvoicecounts.org/scabies-partnership. For more on the EASCP, see https://1disease.org.

The EASCP was developed to enhance regional efforts to reduce the impact of scabies as a public health problem in remote communities of Arnhem Land and is a service delivery program integrated into existing health services. The program’s first goal was to reduce the burden of crusted scabies on affected individuals and households in participating East Arnhem communities. This goal was the result of consultations and baseline clinical audits that indicated a significant burden of illness and ongoing disruption to quality of life arising from unmanaged crusted scabies. Patients we encountered in remote communities in 2011 suffered similar stigma and disfigurement to those described in a case report of crusted scabies published more than 60 years earlier (Box 1).1 The EASCP also recognised that better management of these “core transmitters” was a foundation of broader scabies control efforts.

In late 2011, the EASCP convened a medical working group to update the scabies and crusted scabies guidelines in the Central Australian Rural Practitioners Association (CARPA) Standard treatment manual. Drawing on experience with a patient who had successfully used short-term treatment creams in a preventive fashion, as well as a preventive model proposed in 2004,7 the working group approved a provisional protocol to prevent recurrences of crusted scabies, which the EASCP then trialled.

EASCP crusted scabies case management protocol

The EASCP used active case finding to identify people with crusted scabies. When cases were confirmed in one of the three communities where EASCP had operations, the patients were first treated (in hospital or, when this was declined, in the community) using a protocol developed by the Royal Darwin Hospital.8,9 Patients were then enrolled in the new preventive care regimen, which involved:

- regular (every 1–4 weeks) skin checks looking for signs of recurrent crusted scabies;

- frequent use of a keratolytic cream (to limit the build-up of keratin crusts, where mites live and multiply in crusted scabies) combined with a moisturiser; and

- regular (every 2–4 weeks) use of a scabies (acaricide) cream. The frequency depended on the likely level of recurrent exposure to mites (eg, in a household with many young children, fortnightly applications were used). Benzyl benzoate was selected because of the limited risk of resistance developing with this agent. An initial test application of benzyl benzoate ruled out the side effect of transient burning sensation on the skin.

This clinical protocol was implemented by the EASCP through a long-term household case management approach, focused on developing therapeutic rapport with patients and senior members of households. The EASCP’s early consultations with care providers and patients highlighted significant fear and stigma associated with the disease and a reluctance to engage with health services. Given the chronicity of the disease, the long-term goal was adherence to the treatment regimen and ultimately self-management of the condition. We aimed to achieve this through consistency of staff, regular supply of the preventive creams needed for self-management, and reinforcing the household costs of disease recurrence.

Active case finding and EASCP inclusion criteria

Cases

From August 2011, the EASCP investigated patients identified by health centres as having recurrent scabies or crusted scabies. The EASCP also examined the NT hospital database and related discharge summaries to find patients from participating communities who had been treated for crusted scabies. An experienced EASCP clinician then examined the patient and confirmed or excluded the diagnosis of crusted scabies, and this was verified by visiting dermatologists and infectious disease specialists.

Sentinel contacts

EASCP monitoring paired each confirmed case with a household child contact. The contacts served as sentinels of recurrent disease in the cases and to track their infectivity, as our baseline data showed that most patients with active disease did not present to health services. Contacts were confirmed to have the same primary residence as the cases with whom they were paired. Crusted scabies was excluded in the contacts. Sentinel contacts often had a history of recurrent simple scabies and had been referred to the EASCP for management. Due to capacity constraints, where multiple contacts were known to the EASCP, the contact with the most extensive history of presentation for scabies was selected as the sentinel.

Evaluation of EASCP case management protocol

Between August 2011 and June 2013, seven patients in the three communities under evaluation were confirmed as having crusted scabies and were enrolled in preventive case management. These seven patients and their seven sentinel contacts are included in this review.

EASCP monitoring data consisted of EASCP, health centre and hospital clinical records before and after the preventive care protocol was introduced. The outcome measures examined were the number of presentations involving recurrences of crusted scabies in cases and recurrent simple scabies in contacts. To avoid double counting, each new presentation was recorded as one episode (follow-up visits for multidose treatments were counted only once), and only one episode was recorded if presentations led to referrals to hospital or the health centre for management. Search parameters for the outcome measures were consistent for the intervention (during preventive case management) and control (before preventive case management) periods. However, screening of cases for recurrence was active (1–4-weekly skin checks) during the intervention period, but passive (self-presentation) during the control period. This is likely to significantly bias results towards the null.

The duration of case management was from the time of case identification and consent to June 2013. We examined the change in the number of outcome events during the intervention period compared with those during a pre-intervention control period of the same duration for each case and contact. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to determine statistical significance, and P values < 0.05 were considered significant. Data were analysed using Stata version 11 (StataCorp).

Detailed baseline data and monitoring methods can be found in the Appendix.

Baseline findings

We audited a combined 57 years of clinical records for the seven cases (26 years) and seven contacts (31 years). Among cases, one patient was aged 20–39 years and six were aged 40–59 years. Among contacts, three were aged 0–4 years, three were aged 5–9 years and one was aged 10–14 years.

No immune defect was recorded in the seven cases, apart from one patient who had crusting in a neuropathic limb. Six of the seven patients had active crusting of moderate to severe grade (ie, high infectivity) at the time of first review by the EASCP. Of these six, four had not presented to health services despite having recurrent disease and were only identified through active surveillance. Most (4/6) declined hospitalisation.

Cases presented with recurrent disease a median of five times per year (range, 1–9) during the 26 years of record review. Paired sentinel contacts presented with simple scabies (with or without skin sores) a median of five times per year (range, 0.4–11) during 31 years of record review. Combined case–contact pairs presented a median of 12 times per year (range, 4–16) with presentations related to simple or crusted scabies during the combined 57 years of audited records.

Child contacts had a median of 10 presentations (range, 5–11) for simple scabies and sores in their first year of life, and most contacts had multiple episodes of scabies described as “extensive/whole body”. Nearly all of the paired child contacts had suffered periods of recurrent scabies and sores associated with weight loss and failure to thrive. Five of these children had been referred to child and family services over concerns of parental neglect, where recurrent scabies and sores featured in the referral.

EASCP case management findings

From August 2011 to June 2013, a cumulative total of 99 months of preventive case management was undertaken in the seven cases (mean duration of enrolment in care, 14 months; range, 3–20 months). Clinical records from a matching 99-month control period immediately before preventive case management were also reviewed, making a cumulative total of 198 months before and during the intervention. Clinical records for the corresponding 198 months were examined for paired contacts.

During the 99-month intervention period, cases were reviewed at 1–4-weekly intervals. For the seven cases, a total of 245 skin checks were performed in the community (every 1.6 weeks on average). The EASCP recorded no reports of adverse effects from the preventive treatment regimen.

For the seven cases, we detected a significant 44% reduction in clinically diagnosed episodes of recurrence of crusting (from 36 to 20; P = 0.025) during the intervention period, compared with the control period (Box 2). We also detected a 56% reduction in episodes of hospitalisation (from 9 to 4; P = 0.09) and an 80% reduction in days spent in hospital as a result of recurrence of crusted scabies (from 173 to 35; P = 0.09), compared with the control period. However, these changes were not significant and are due to the number of cases that had not recorded a hospitalisation and, in light of our baseline data, are likely to indicate non-presenters.

For the seven paired contacts, we detected a statistically significant 75% decrease in the combined number of hospital admissions and presentations to local health centres with scabies and skin sores (from 28 to 7; P = 0.017) during the intervention period, compared with the control period (Box 2). We also detected a significant 58% reduction in paired case–contact presentations (from 64 to 27; P = 0.016).

Limitations of the evaluation

The nature of the analysis (involving audit of program monitoring records) and the small sample size limit the generalisability of our findings. The routine nature of data collection means there is interoperator variability, and diagnoses made on clinical grounds allow for false-positive results. For cases, this is likely to be low because recurrences were based on detection of characteristic skin lesions in patients who had a hospital- or specialist-confirmed history of crusted scabies. Importantly, the criteria were consistent during the intervention and control periods. We believe our method of analysis is conservative, with the dominant bias being towards the null, as surveillance for recurrences was active during the intervention period, compared with passive surveillance during the control period. The use of a primary contact to track disease transmission also limits generalisability of the study. However, the contacts act as useful sentinels of recurrent disease and infectivity of cases. EASCP monitoring is ongoing, and subsequent analyses will improve the generalisability of findings as the duration of follow-up and number of managed cases increases.

Lessons

EASCP’s program monitoring and evaluation findings offer important lessons for the control of crusted and simple scabies in Australia.

Lesson 1: Current passive surveillance for recurrences leads to likely underdetection of crusted scabies in scabies-endemic areas.

Lesson 2: Combined presentations of cases and sentinel contacts suggest significant scabies transmission from cases to household contacts, increasing the risk of complications from chronic renal and rheumatic heart disease. Repeated episodes of scabies and skin sores are likely to significantly impair household quality of life,10 and to increase the risk of repeated exposure to group A streptococcus isolates, which has been associated with increased risk of chronic renal and rheumatic heart disease.11,12

Lesson 3: Skin disfigurement and weight loss associated with recurrent scabies and skin sore infections may have led to child contacts being misdiagnosed as victims of parental neglect. Recurrent infections can lead to weight loss as a result of altered metabolism, nutrient loss and decreased appetite. Malnutrition in turn lowers immunity and susceptibility to infections.13–15 Thus, in contacts of patients with crusted scabies, weight loss and skin disfigurement associated with severe recurrent scabies and skin sores are likely to signify ongoing disease transmission from infected patients, rather than parental neglect.

Lesson 4: EASCP case management appears to reduce the burden of illness in patients with crusted scabies. Due to the differential screening methods used in the intervention (active) versus control (passive) periods, the actual reduction in recurrences during EASCP preventive care (and duration of time patients remained disease-free, compared with time spent with active crusting) is likely to be significantly greater than the 44% decrease we observed.

Lesson 5: EASCP case management reduces simple scabies presentations in sentinel contacts. The decrease we detected in presentations of contacts is likely to signify less time spent unwell from recurrent scabies and sores and thus less suffering, disfigurement and stigmatisation. EASCP case management thus provides a way to reduce the long-term disruption to quality of life for these households.10 At the community level, our findings suggest the improved control of an important driver of scabies endemicity.3–5,11 The reduced infectivity of cases can be explained by two novel features of the EASCP preventive care regimen: ongoing skin checks, allowing early detection of recurrences; and regular use of keratolytic and scabicide agents, both of which inhibit mite hyperinfestation.

Recommendations

Based on the EASCP’s preliminary findings, and in light of the disruption caused by the condition to affected households, we recommend that patients with crusted scabies living in scabies-endemic areas be offered this preventive care regimen. The crusted scabies guidelines in the forthcoming 6th edition of the CARPA Standard treatment manual have been revised to feature this model of care, and our recommendations to facilitate its wider adoption are shown in Box 3.

1 The disfiguring plaques of crusted scabies

2 Review of cases of crusted scabies and paired contacts before and during East Arnhem Scabies Control Program (EASCP) household preventive case management

| |

Control (pre-intervention) period

|

Intervention period

|

Change

|

P

|

|

|

Cases (n = 7)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Months audited

|

99

|

99

|

—

|

|

|

Hospital admissions for recurrences

|

9

|

4

|

− 56%

|

0.09

|

|

Days in hospital

|

173

|

35

|

− 80%

|

0.09

|

|

EASCP or health centre-diagnosed recurrences

|

27

|

16

|

− 41%

|

0.04

|

|

Total recurrences (rate per year)

|

36 (4.4)

|

20 (2.4)

|

− 44%

|

0.025

|

|

Contacts (n = 7)

|

|

|

|

|

|

Months audited

|

99

|

99

|

—

|

|

|

Hospital admissions for severe infected scabies

|

3

|

0

|

− 100%

|

0.16

|

|

Days in hospital

|

13

|

0

|

− 100%

|

0.16

|

|

Health centre presentations for scabies skin sores

|

25

|

7

|

− 72%

|

0.017

|

|

Total scabies-related presentations (rate per year)

|

28 (3.4)

|

7 (0.8)

|

− 75%

|

0.017

|

|

Paired case–contact presentations

|

64

|

27

|

− 58%

|

0.016

|

3 Recommendations for implementing the preventive care regimen of the East Arnhem Scabies Control Program (EASCP)

Wider adoption of the preventive regimen for patients with crusted scabies living in scabies-endemic areas will require:

- Ongoing program monitoring and operational research to refine preventive case management protocols and document the transferability of programs

- Active surveillance for recurrences and a chronic disease case management approach to crusted scabies care — a long-term therapeutic approach is more likely to lead to better outcomes than an acute-outbreak approach and to overcome the fear, stigma and avoidance of health services evident in most patients’ clinical histories

- Support from regional disease control and chronic disease programs for health centres to adopt this new model of care in communities

- A regional register to facilitate continuity of care when patients move between communities — for this, a diagnostic criterion for “recurrent” crusted scabies must be developed, and we recommend adopting Grades 2–3 of the Royal Darwin Hospital grading scale as a criterion for inclusion in ongoing preventive care9

- Investigation of the household to exclude contact with crusted scabies in situations where recurrent scabies, skin sores and weight loss are seen in a child; in households where crusted scabies is present, a diagnosis of parental neglect due to recurrent scabies and weight loss in children should be made with extreme caution

- Urgent research and development to bring easier-to-use and more effective crusted scabies (and simple scabies) therapies, including immunotherapies, to the market

more_vert

more_vert