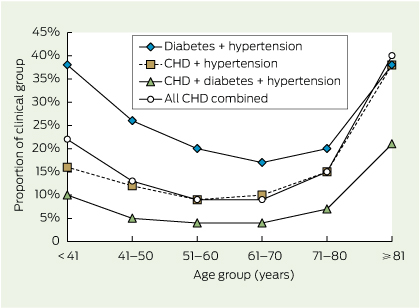

Deliberate yet judicious deprescribing has considerable potential to relieve unnecessary medication-related suffering and disability in vulnerable older populations. Polypharmacy — variously defined as more than five or up to 10 or more medications taken regularly per individual — is common among older people (defined here as those aged 65 years or over). Depending on the circumstances, including why and how drugs are being administered, polypharmacy can be appropriate (potential benefits outweigh potential harms) or inappropriate (potential harms outweigh potential benefits).

While many older people benefit immeasurably from multiple drugs, many others suffer adverse drug events (ADEs). In Australia, one in four community-living older people are hospitalised for medication-related problems over a 5-year period1 and 15% of older patients attending general practice report an ADE over the previous 6 months.2 At least a quarter of these ADEs are potentially preventable.2 Up to 30% of hospital admissions for patients over 75 years of age are medication related, and up to three-quarters are potentially preventable.3 Up to 40% of people living in either residential care4 or the community5 are prescribed potentially inappropriate medications. In both hospital and primary care settings, about one in five prescriptions issued for older adults are deemed inappropriate.6

Polypharmacy in older people is associated with decreased physical and social functioning; increased risk of falls, delirium and other geriatric syndromes, hospital admissions, and death; and reduced adherence by patients to essential medicines. The financial costs are substantial, with ADEs accounting for more than 10% of all direct health care costs among affected individuals.7

The single most important predictor of inappropriate prescribing and risk of ADEs is the number of medications a person is taking; one report estimated the risk as 13% for two drugs, 38% for four drugs, and 82% for seven drugs or more.8 One in five older Australians are receiving more than 10 prescription or over-the-counter medicines.9 People in residential aged care facilities are prescribed, on average, seven drugs,10 while hospitalised patients average eight.11 While hospitalisation might provide an opportunity to review medication use, on average, while two to three drugs are ceased, three to four are added.12

In responding to polypharmacy-related harm, a new term has entered the medical lexicon: deprescribing. This is the process of tapering or stopping drugs using a systematic approach (Box).13 Inculcating a culture of deprescribing will be challenging for several reasons.

Barriers to deprescribing

Underappreciation of the scale of polypharmacy-related harm

Clinicians easily recognise clinically evident ADEs with clear-cut causality. In contrast, ADEs mimicking syndromes prevalent in older patients — falls, delirium, lethargy and depression — account for 20% of ADEs in hospitalised older patients but go unrecognised by clinical teams.14

Increasing intensity of medical care

The drivers of polypharmacy are multiple: disease-specific clinical guideline recommendations, quality indicators and performance incentives;15 a focus on pharmacological versus non-pharmacological options; and “prescribing cascades”, when more drugs are added in response to onset of new illnesses, including ADEs misinterpreted as new disease.

Narrow focus on lists of potentially inappropriate medications

Lists of potentially inappropriate medications (such as the Beers, McLeod and STOPP [Screening Tool of Older Persons’ Potentially Inappropriate Prescriptions] criteria)16 comprise drugs whose benefits are outweighed by harm in most circumstances. Examples include potent opioids used non-palliatively, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, anticholinergic drugs and benzodiazepines. However, such drugs account for relatively few ADEs in Australian practice.17 In contrast, commonly prescribed drugs with proven benefits in many older people, such as cardiovascular drugs, anticoagulants, hypoglycaemic agents, steroids and antibiotics, are more frequently implicated as a result of misuse.18

Reluctance of prescribers and ambivalence of patients

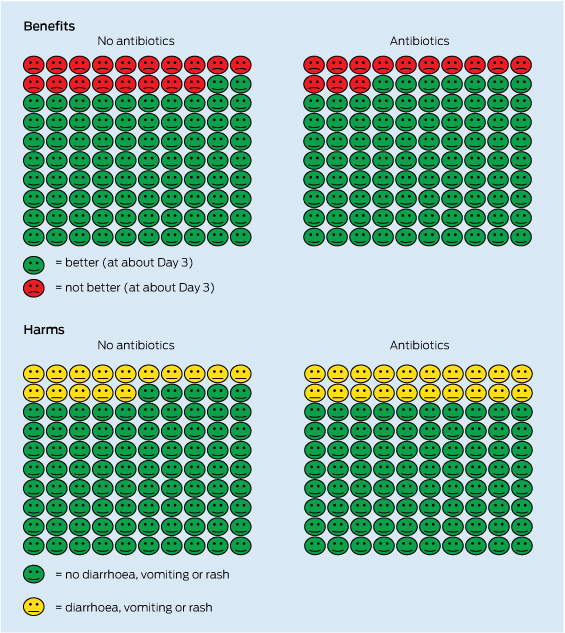

Many prescribers feel uneasy about ceasing drugs for several reasons:19,20 going against opinion of other doctors (particularly specialists) who initiated a specific drug and which patients appear to tolerate; fear of precipitating disease relapse or drug withdrawal syndromes or patient approbation at having their care “downgraded”; paucity of precise benefit–harm data for specific medications to guide selection for discontinuation; apprehension around discussing life expectancy versus quality of life in rationalising drug regimens; limited time and remuneration for reappraising chronic medications, discussing pros and cons with patients, and coordinating views and actions of multiple prescribers.

While agreeing in principle to minimising polypharmacy, patients simultaneously express gratitude that their drugs may prolong life, abate symptoms and improve function. Fear of relapsing disease lessens patients’ desire to discontinue a drug, especially if combined with negative past experiences. Inability to see the personal relevance of harm–benefit trade-offs or lack of trust in their doctors’ advice about drug inappropriateness and the safety of discontinuation plans also act against deprescribing.21

Possible solutions

Ultimately, deprescribing is a highly individualised and time-consuming process, but several facilitative strategies are offered.

Reframe the issue

Both the patient and clinician should regard deprescribing as an attempt to alleviate symptoms (of drug toxicity), improve quality of life (from drug-induced disability) and lessen the risk of morbid events (ADEs) in the future. Its objective is not simply to reduce the burden, inconvenience or costs of complex drug regimens, although these too are potential benefits. Deprescribing should not be seen by patients as an act of abandonment but one of affirmation for highest quality care and shared decision making. Compelling evidence that identifies circumstances in which medications can be safely withdrawn while reducing the risk of ADEs and death needs to be emphasised.22–25

Discuss benefit–harm trade-offs and assess willingness

In consenting to a trial of withdrawal, patients need to know the benefit–harm trade-offs specific to them of continuing or discontinuing a particular drug. Patient education initiatives providing such personalised information can substantially alter perceptions of risk and change attitudes towards discontinuation.26

Target patients according to highest ADE risk

In addition to medication count, other ADE predictors include past history of ADEs, presence of major comorbidities, marked frailty, residential care settings and multiple prescribers.

Target drugs more likely to be non-beneficial

Such drugs, as initial targets for deprescribing, consist of five types.

- Drugs to avoid if at all possible (comprising those previously cited in “drugs to avoid” lists16).

- Drugs lacking therapeutic effect for substantiated indications despite optimal adherence over a reasonable period of time.

- Drugs that patients are unwilling to take for various reasons, including occult drug toxicity, difficulty handling medications, costs and little faith in drug efficacy.

- Drugs lacking a substantiated indication, either because the original disease diagnosis was incorrect — as often occurs with regard to heart failure, Parkinson disease and depression — or because the stated diagnosis-specific indication is invalid owing to evidence of harm or no benefit. Importantly, indications or treatment targets derived from studies involving younger patients or highly selected, older individuals with a single disease may be inappropriate for older, frail patients with multimorbidity.

- Drugs that are unlikely to prevent disease events within the patient’s remaining life span. The question here is not how much benefit drugs aimed at preventing future disease events (such as statins and bisphosphonates) may confer, but when. If the time until benefit exceeds the patient’s estimated life span, no benefit will result, while the ADE risk is constant and immediate. Undertaking such reconciliations is facilitated by accurate estimation of longevity using easy-to-use web-based mortality indices (eg, see http://eprognosis.ucsf.edu) and drug-specific time until benefit using trial-based time-to-event data.27

Access and apply specific discontinuation regimens

Detailed descriptions of how clinicians can safely withdraw specific drugs and monitor for adverse effects can be found within various articles and websites.28,29

Foster shared education and training

Interactive, case-based, interdisciplinary meetings involving multiple prescribers, combined with deprescribing advice from clinical pharmacologists or appropriately trained pharmacists have been shown to be beneficial with regard to doctors’ deprescribing practice.30

Extend the time frame with the same clinician

Several patient encounters with the same overseeing generalist clinician, focused on one drug at a time, can provide repeated opportunities to discuss and assuage a patient’s fear of discontinuing a drug and to adjust the deprescribing plan according to changes in clinical circumstances and revised treatment goals. Deprescribing can be remunerated under extended care or medication review items, with patients’ full awareness that such consultations are expressly for reviewing medications.

Conclusion

Inappropriate polypharmacy and its associated harm is a growing threat among older patients that requires deliberate yet judicious deprescribing using a systematic approach. Widespread adoption of this strategy has its challenges, but also considerable potential to relieve unnecessary suffering and disability, as embodied in that basic Hippocratic dictum — first do no harm.

Core themes in deprescribing13

- Ascertain all current medications (medication reconciliation)

- Identify patients at high risk of adverse drug events

- number and type of drugs

- patient characteristics (physical, mental, social impairments)

- multiple prescribers

- Estimate life expectancy in high-risk patients

- with focus on patients with prognosis equal to or less than 12 months

- Define overall care goals and patient values and preferences in the context of life expectancy

- relativity of symptom control and quality of life v cure or prevention

- patient preference for aggressive v conservative care; willingness to consider deprescribing

- Define and validate current indications for ongoing treatment

- medication–diagnosis reconciliation

- drugs lacking valid indications are candidates for discontinuation

- Determine time until benefit for preventive or disease-modifying medications

- drugs whose time until benefit exceeds expected life span are candidates for discontinuation

- Estimate magnitude of benefit v harm in absolute terms for individual patient

- drugs with little likelihood of benefit and/or significant risk of harm are candidates for discontinuation

- Implement and monitor a drug deprescribing plan

- ongoing reappraisal for illness relapse or deterioration or withdrawal syndromes

- communication of plan and shared responsibility among all prescribers

- supervision of drug discontinuation by single generalist clinician

more_vert

more_vert