A career in medicine has long been considered an apprenticeship, with mentors providing guidance to their trainees. The word mentor finds its origins in Greek mythology. In Homer’s Odyssey, the confidant of king Odysseus, Mentor, was trusted to guide his son and oversee his education while Odysseus fought in the Trojan War.1

The modern practice of medicine, with an emphasis on shift work, has made the classical mentor–mentee relationship more challenging,2 but the modelling of one’s practice on observed social and clinical traits of a mentor or role model remains.3 Moreover, such exposures can be factors in students’ decisions to pursue a career in medicine and even in their subsequent choice of specialty.4

The eventual choice of role model is often a personal one and may not even involve one’s own supervising senior, although it is often based on clinical experiences.5 While knowledge and clinical competence have been cornerstones of role model selection, growing evidence suggests that factors relating to personality such as compassion, good communication and enthusiasm may in fact have more influence on the expanding minds of trainees.6 Further compounding this, in some educational situations, less than half of senior clinicians were subsequently identified as being excellent role models.7

While social interactions with parents, teachers or even peers may impact on personality, outlook and practice, other media such as literature and television (TV) have been demonstrated to be significant components of this role model hypothesis.8

Medical TV programs have grown in popularity from the 1960s onwards and are now considered a staple of primetime TV.9 It has only been in more recent years that the effects of these health and illness TV narratives have been studied in greater detail.

Although their true purpose has been one of entertainment, much of their appeal is based on the perception that they are an accurate reflection of reality.10

It has been well accepted that TV can have an impact on society, increasing knowledge and influencing behaviour.11 TV medical dramas have also been shown to be of educational worth to patients12 and even doctors.13

However, they have occasionally come under criticism for unrealistic medical content, ranging from demonstration of intubation technique14 to cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).15 Frequently, in CPR situations on TV compared with actual practice, there is a higher volume of trauma cases as an underlying aetiology. Further, these scenarios often show considerably younger patients than those seen in routine CPR and survival to discharge is much better than clinically encountered.16 Concerns that this may influence the attitudes of members of the public who watch these dramas for educational purposes remain.

More recently, there has been a growing emphasis on the use of these programs as educational resources.17 In particular, some of the established role model personality traits such as ethical astuteness, communication and empathy have been sufficiently demonstrated in these series to warrant use in undergraduate teaching videos.18 Although much of the learning that can be gleaned from observing the practices of TV doctors has focused on perceived softer undergraduate educational domains,19 their use in postgraduate settings is also increasing.20

TV is a medium through which many health care workers not only take their minds off work, but also reflect both consciously and unconsciously on experiences. Students and doctors do indeed watch these programs at least as often as the general public does and, when questioned, are quite positive regarding them.21 Although not yet demonstrated, watching these series may form an early part of any role modelling or identification with certain character traits that both trainee and established medical practitioners may have.

Methods

A structured questionnaire was distributed among doctors of all grades and specialties in three large teaching hospitals in Wales, United Kingdom (Morriston Hospital, Singleton Hospital and Princess of Wales Hospital) within the Abertawe Bro Morgannwg (ABM) University Health Board, to allow capture of data from a diverse range of specialties. These were disseminated through various different locations, including departmental meetings and on-call rooms.

Questions related to respondents’ gender, specialty and grade, whether they watched medical TV dramas and their opinions regarding them, and whether they identified with characters from these programs (and if so, who) or with a non-fictional doctor encountered during their clinical careers.

Hospital grades were summarised as consultant, specialist trainee (registrar), core trainee (resident medical officer [RMO]), and foundation doctor (intern). For simplification, specialties was separated into medical, surgical, acute (eg, accident and emergency, intensive care unit, etc) and non-acute (eg, pathology, radiology, etc), although note was made of individual subspecialty answers from within these broader categories.

Statistical analysis

A cumulative odds ordinal logistic regression with proportional odds was run to determine the effect of grade and specialty on the choice and frequency of viewing of medical TV dramas. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Statistical calculations were performed using SPSS Statistics, version 21.0 (IBM).

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted by the ABM University Health Board Research and Development Joint Scientific Review Committee.

Results

Three hundred and seventy-two questionnaires were disseminated and 200 completed questionnaires were returned (response rate, 54%). Forty-six per cent of individuals completing questionnaires were women and 88% had graduated from a UK medical school. Grades and specialties of respondents are presented in Box 1.

How often do clinicians watch TV medical dramas?

One hundred and twenty-nine doctors (65%) surveyed admitted to watching TV medical dramas on more than one occasion and 14% considered themselves to be regular viewers; 15% of respondents felt that watching them as a school student positively influenced their decision to pursue a medical career.

Junior doctors were five times more likely to have watched these programs as medical students compared with more senior doctors (odds ratio [OR], 5.2; 95% CI, 2.5–10; P < 0.01). The ORs for RMOs and specialist trainees were 3.1 and 2.5, respectively, in relation to consultants (P < 0.05). Further, UK graduates were five times more likely to have watched these medical TV dramas as medical students compared with non-UK graduates (OR, 4.8; 95% CI, 2.4–9.6; P < 0.01).

The most commonly watched TV programs were Scrubs (49%), House MD (35%) and ER (21%). Most doctors who admitted to watching medical dramas did so for entertainment purposes (69%); 19% watched because there was nothing else on TV; 5% for insight into media perceptions of medical practice; and 8% for educational purposes.

Clinicians’ opinions regarding TV medical dramas

We asked individuals if they felt that TV medical dramas were educational, gave doctors a bad name, accurately showed the doctor–nurse relationship, and represented the spectrum of illnesses commonly encountered.

One hundred and three respondents (52%) felt that these shows displayed no educational value whatsoever, 52 (26%) were unsure, and 45 (23%) believed there were some educational benefits from watching them.

Evaluating the spectrum of illness represented in these dramas, 82% felt that those shown were unrealistic of daily practice. However, 20 respondents (10%) thought that they accurately portrayed reality. Most of these positive responses (16/20) were from junior doctors. No associations between the belief that medical dramas portrayed realistic life situations and specialty or frequency of viewing were observed.

Grade, specialty and country of qualification had no effect on whether a doctor believed that the programs represented current medical practice. Neither did current frequent watching or having been a regular viewer at undergraduate level.

Twenty-seven per cent of doctors surveyed felt that these programs gave doctors a bad name, although no significant differences were observed between any of the groups.

Only 13% of respondents felt that medical dramas accurately portrayed the doctor–nurse relationship, most of whom were self-admitted non-regular viewers (P = 0.01) and general practitioners or GP trainees (19/25; P = 0.05).

Outcomes of watching TV medical dramas

Thirty per cent of foundation doctors (interns) and 25% of core trainees (RMOs) felt that watching medical TV programs may have affected their career choice (to any extent) compared with more senior doctors (18%).

Compared with consultants, the OR for interns considering that watching medical TV dramas had any effect on their subsequent career choices was 4.8 (95% CI, 1.6–13.7; P = 0.013); for RMOs and specialist trainees, the ORs were 2.5 (95% CI, 1.3–5.8) and 2.7 (95% CI, 1.3–5.8) respectively; P = 0.09 and 0.13).

Specialty and country of qualification did not influence doctors’ beliefs that watching medical dramas had an effect on their career choice.

Clinicians’ identification with doctors in TV medical dramas?

A total of 121 respondents (61%) role modelled aspects of their practice on another doctor (fictional and non-fictional).

Junior doctors, particularly interns and RMOs were more likely to find commonality in their practice with fictional TV characters compared with more senior doctors (OR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.3–5.8; P = 0.008).

Consultants were most likely not to specify any role models and, if they did so, were more likely to identify themselves with non-fictional characters (32/55) compared with other doctors, particularly interns (4/49).

Medical doctors were more likely to identify themselves with a fictional TV character (OR, 3.2; 95% CI, 1.08–9.43; P = 0.035). This was followed by 19% of acute specialty doctors and 14% of surgical specialty doctors. Non-acute specialty doctors were least likely to identify themselves with a fictional TV doctor.

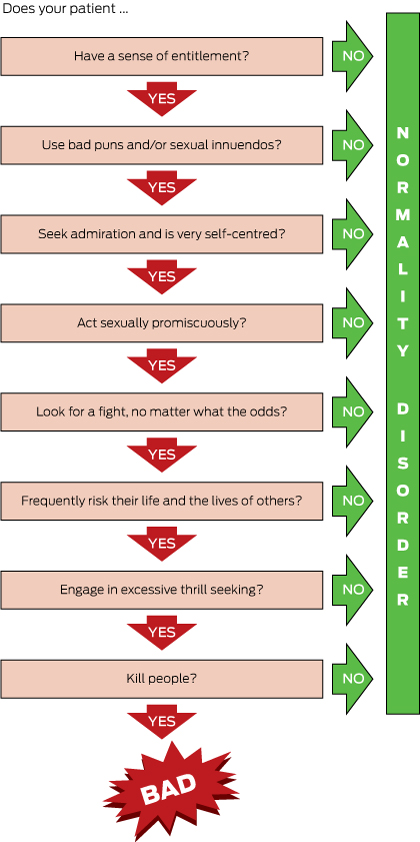

The top five most popular fictional role models are shown in Box 2. Leonard McCoy (Star Trek) and Quincy (Quincy ME) were the most popular choices among consultants; the majority of positive responders were anaesthetists and pathologists. A more varied response was seen among physicians and surgeons, but note was made of a peculiar popular choice: Dr Evil (from the Austin Powers film series, Box 3) was named by four trainees, all surgical (three orthopaedic and one general surgery).

Discussion

There is a known association between clinical role models in undergraduate medicine and career choice.22 Therefore, TV medical dramas could potentially influence doctors’ and students’ opinions and have been found to be a source of entertainment for both health care professionals as well as the wider public.23

Fictional doctors have evolved into television heroes and much of their appeal is their on-screen personality as well as, in some cases, their absolute prioritisation of scientific challenge over social relationships.24 Further, much of their appeal is their ability to navigate through difficult ethical dilemmas, to make decisions that are often perceived by clinical trainees as being positive ones.25

Although clinicians watching these programs appear to do so predominantly for entertainment purposes, we found that those who watch for educational reasons show that junior trainees exposed to this genre of TV entertainment are more influenced by these series than their more senior counterparts. Interestingly, all respondents who admitted to watching TV medical dramas for educational reasons watched House MD (Box 4), perhaps suggesting that they value its learning input.

In keeping with previous studies,14–16 most doctors felt that a large proportion of what was televised may not be a true representation of clinical practice; however, suggestions that more junior trainees believe this to be so could be explained by their relative lack of clinical experiences to date.

Identifying aspects of one’s practice with witnessed exposures has been a cornerstone of the role modelling theory, but data generated from this questionnaire-based study suggest some interesting differences between specialties. Doctors who answered negatively to currently viewing or having ever viewed this type of program were least likely to admit to having been influenced into a career in medicine on the basis of TV medical dramas, thus validating the data.

It is to be assumed that consultants may look on their past seniors as role models to identify commonality of practice but the high proportion of respondents among all grades who admitted to being influenced, at least in part, by medical TV dramas suggests a much higher effect than anticipated.

Further, differences between specialities — for example, medical doctors identifying more with TV doctors compared with their surgical peers — might be explained by the sizeable volume of medically themed programs as opposed to more surgical ones. It is plausible, however, that some of the core learning traits seen in physicianly specialties, particularly regarding difficult diagnostics and ethical dilemmas, strike a chord with this group of clinicians. Specific choice of TV doctor hero as a potential role model will require further evaluation. Motivations for the popular choice of a Star Trek character among anaesthetists may include an interest in futuristic technology. Likewise, the interesting preference for Dr Evil among some surgical trainees may be due to an interest in world and/or career domination, or it may be suggestive of professional ambition rather than a display of true megalomaniac traits.

While we may be some years from continuing medical education creditation obtained from Saturday evening viewing, this study does suggest that the current generation of junior doctors relies on medical TV dramas for entertainment and education in parallel. Further observation may show some interesting effects during career progression, particularly regarding the atypical answers we received to our questions about TV doctor identification.

Box 1 –

Grade and specialty of respondents (n = 200)

|

Grade and specialty

|

No. (%)

|

|

|

Grade

|

|

|

Intern

|

49 (24.5%)

|

|

Core trainee (RMO)

|

60 (30.0%)

|

|

Registrar (specialist trainee)

|

36 (18.0%)

|

|

Consultant

|

55 (27.5%)

|

|

Specialty

|

|

|

Medical

|

83 (41.5%)

|

|

Surgical

|

36 (18.0%)

|

|

Acute non-medical

|

27 (13.5%)

|

|

Non-acute

|

20 (10.0%)

|

|

GP or GP trainee

|

34 (17.0%)

|

|

|

RMO = resident medical officer.

|

Box 2 –

Most popular fictional television doctor role models

|

Rank

|

Doctor

|

Show

|

Most popular among:

|

|

|

1

|

Elliot Reid

|

Scrubs

|

Women, junior trainees

|

|

2

|

Perry Cox

|

Scrubs

|

Specialist trainees, physicians

|

|

3

|

Leonard McCoy

|

Star Trek

|

Consultants, anaesthetists

|

|

4

|

John Carter

|

ER

|

Physicians, acute specialties

|

|

5

|

R Quincy

|

Quincy ME

|

Consultants, non-acute specialties (pathologists)

|

|

|

|

Box 3 –

Dr Evil (Austin Powers film series) was an interesting selection among some surgical trainees (Getty Images)

Box 4 –

House MD was considered the most educational among respondents (Getty Images)

more_vert

more_vert