The prevalence of antibiotic allergy labels (AAL) has been estimated to be 10–20%.1,2 AALs have been shown to have a significant impact on the use of antimicrobial drugs, including their appropriateness, and on microbiological outcomes for patients.3,4 Many reported antibiotic allergies are, in fact, drug intolerances or side effects, or non-recent “unknown” reactions of questionable clinical significance. Incorrect classification of patient AALs is exacerbated by variations in clinicians’ knowledge about antibiotic allergies and the recording of allergies in electronic medical records.5–7 The prevalence of AALs in particular subgroups, such as the elderly, remains unknown; the same applies to the accuracy of AAL descriptions and their impact on antimicrobial stewardship. While models of antibiotic allergy care have been proposed8,9 and protocols for oral re-challenge in patients with “low risk allergies” successfully employed,10 the feasibility of a risk-stratified direct oral re-challenge approach remains ill defined. In this multicentre, cross-sectional study of general medical inpatients, we assessed the prevalence of AALs, their impact on prescribing practices, the accuracy of their recording, and the feasibility of an oral antibiotic re-challenge study.

Methods

Study design, setting and population

Austin Health and Alfred Health are tertiary referral centres located in north-eastern and central Melbourne respectively. This was a multicentre, cross-sectional study of general medical inpatients admitted between 18 May 2015 and 5 June 2015; those admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU), emergency unit or short stay unit were excluded from analysis.

At 08:00 (Monday to Friday) during the study period, a list of all general medical inpatients was generated. Baseline demographics, comorbidities (age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity index11), infection diagnoses, and inpatient antibiotic medications (name, route, frequency) were recorded. Patients with an AAL were identified from drug charts, medical admission notes, or electronic medical records (EMRs). A patient questionnaire was administered to clarify AAL history (Appendix), followed by correlation of the responses with allergy descriptions in the patient’s drug chart, EMR and medical admission record. To maintain consistency, this questionnaire was administered by pharmacy and medical staff trained at each site. Patients with a history of dementia or delirium who were unable to provide informed consent were excluded only from the patient questionnaire component of the study. A hypothetical oral antibiotic re-challenge in a supervised setting was offered to patients with a low risk allergy phenotype (Appendix).

Definitions

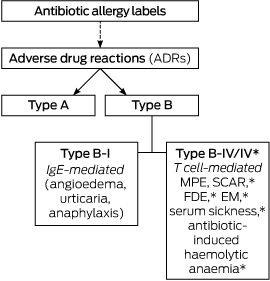

An AAL was defined as any reported antibiotic allergy or adverse drug reaction (ADR) recorded in the allergy section of the EMR, drug chart, or medical admission note. AALs were classified as either type A or type B ADRs according to previously published definitions (Box 1):12,13

-

type A: non-immune-mediated ADR consistent with a known drug side effect (eg, gastrointestinal upset);

-

type B: immune-mediated reactions consistent with an IgE-mediated (eg, angioedema, anaphylaxis, or urticaria = type B-I) or a T cell-mediated response (type B-IV):

-

Type B-IV: delayed benign maculopapular exanthema (MPE);

-

Type B-IV* (life-threatening in nature): severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCAR),14 erythema multiforme (EM), fixed drug eruption (FDE), serum sickness, and antibiotic-induced haemolytic anaemia.

Study investigators JAT and AKA categorised AALs; if consensus could not be reached, a third investigator (LG) was recruited to adjudicate.

An AAL was defined as a “low risk phenotype” if it was consistent with a non-immune-mediated reaction (type A), delayed benign MPE without mucosal involvement that had occurred more than 10 years earlier (type B-IV), or an unknown reaction that had occurred more than 10 years earlier. Unknown reactions in patients who could not recall when the reaction had occurred were also classified as low risk phenotypes. All low risk phenotypes were ADRs that did not require hospitalisation. A “moderate risk phenotype” included an MPE or unknown reaction that had occurred within the past 10 years. A “high risk phenotype” was defined as any ADR reflecting an immediate reaction (type B-I) or non-MPE delayed hypersensitivity (type B-IV*).

AAL mismatch was defined as non-concordance between a patient’s self-reported description of an antibiotic ADR in the questionnaire and the recorded description in any of the medical record platforms (drug charts, medical admission notes, EMR). Infection diagnosis was classified according to Centers for Disease Control/National Healthcare Safety definitions.15

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in Stata 12.0 (StataCorp). Variables of interest in the AAL and no antibiotic allergy label (NAAL) groups were compared. Categorical variables were compared in χ2 tests, and continuous variables with the Wilcoxon rank sum test. P < 0.05 (two-sided) was deemed statistically significant.

Ethics approval

The human research ethics committees of both Austin (LNR/15/Austin/93) and Alfred Health (project 184/15) approved the study.

Results

Antibiotic allergy label description and classification

The baseline patient demographics for the AAL and NAAL groups are shown in Box 2. Of the 453 patients initially identified, 107 (24%) had an AAL. A total of 160 individual AALs were recorded: 27 were type A (17%), 26 were type B-I (16%), 45 were type B-IV (28%), and 62 were of unknown type (39%) (Box 3). Sixteen of the type B-IV reactions (35%) were consistent with more severe phenotypes (type B-IV*). When the time frame criterion (more than 10 years v 10 years or less since the index reaction) was applied to phenotype definitions, this translated to 63% low risk (101 of 160), 4% moderate risk (7 of 160), and 32% high risk (52 of 160) phenotypes. The antibiotics implicated in AALs and their ADR classifications are summarised in Box 3; 34% of reactions were to simple penicillins, 13% to sulfonamide antimicrobials, and 11% to cephalosporins. Three AAL patients (2.8%) were referred to an allergy specialist for assessment (one with type A, two with type B-I reactions). No recorded AALs were associated with admission to an ICU, while eight either ended or occurred during the index hospital admission (two type A, five type B-I, and one type B-IV).

Antibiotic use

Ceftriaxone was prescribed more frequently for patients with AALs (29 of 89 [32%]) than for those in the NAAL group (74 of 368 [20%]; P = 0.02); flucloxacillin was prescribed less frequently (0 v 21 of 368 [5.7%]; P = 0.02). The rate of prescription of other restricted antibiotics, including carbapenems, monobactams, quinolones, glycopeptides and lincosamides, was low in both groups (Box 4).

Antibiotic cross-reactivity

Seventy patients had a documented reaction to a penicillin (a total of 72 penicillin AALs: 55 to penicillin V or G, eight to aminopenicillins, nine to anti-staphylococcal penicillins), including two patients with two separate penicillin allergy labels to members of different β-lactam classes. Of these, 23 (32.9%) were prescribed and tolerated cephalosporins (Box 5). Of the 55 patients with a penicillin V/G AAL, β-lactam antibiotics were prescribed for 19 patients (34%); one patient received aminopenicillins (1.8%), four first generation cephalosporins (7%), two second generation cephalosporins (3.6%), and 12 received third generation cephalosporins (21.8%). Conversely, 18 patients had documented ADRs to cephalosporins, with a total of 19 AALs (14 to first generation, one to second generation, two to third generation cephalosporins, and two to cephalosporins of unknown generation). Of these, five patients (27.8%) were again prescribed cephalosporins without any reaction, and a further five (27.8%) tolerated any penicillin (Box 5).

Eight patients with AALs (7%) were administered an antibiotic from the same antibiotic class. No adverse events were noted in any of the patients inadvertently re-challenged. Eighty-six AAL patients (77%) reported a history of taking any antibiotic after their index ADR event. Thirteen patients (12%) believed they had previously received an antibiotic to which they were considered allergic, 62 had not (58%), and 32 were unsure (30%).

Recording of AALs

Almost all AALs (156 of 160 [98%]) were documented in medication charts, but only 115 (72%) were documented in admission notes and 81 (51%) in the EMR. Twenty-five per cent of patients had an AAL mismatch. No patients received the exact antibiotic recorded in the AAL.

Hypothetical oral antibiotic re-challenge

Fifty-eight AAL patients (54%) were willing to undergo a hypothetical oral antibiotic re-challenge in a supervised environment, of whom 28 (48%) had a low risk phenotype, seven a moderate risk phenotype (12%), and 23 a high risk phenotype (40%). If patients had received and tolerated an antibiotic to which they were previously considered allergic, they were more likely to accept a hypothetical re-challenge than those who had not (9 of 12 [75%] v 3 of 12 [25%]; P = 0.04).

Discussion

The major users of antibiotics in community and hospital settings remain our expanding geriatric population.16 An accumulation of AALs, reflecting both genuine allergies (immune-mediated) and drug side effects or intolerances, follows years of antibiotic prescribing. This is reflected in the high AAL prevalence (24%) in our cohort of older Australian general medical inpatients, notably higher than the national average (18%) and closer to that reported for immune-compromised patients (20–23%).4,17

To understand the high prevalence of AALs and the predominance of low risk phenotypes in our study group requires an understanding of “penicillin past”, as many AALs are confounded by the impurity of early penicillin formulations and later penicillin contamination of cephalosporin products.18,19 Re-examining non-recent AALs of general medical inpatients is therefore potentially both a high yield and a low risk task, considering the low pre-test probability of a persistent genuine penicillin allergy.20–22 While the definition of a low risk allergy phenotype is hypothetical, it is based upon findings that indicate the loss of allergy reactivity over time,20,21,23 the low rate of adverse responses to challenges in patients with mild delayed hypersensitivities,20,22,23 and the safety of oral challenge in patients with similar phenotypes.24

The high rate of type A, non-severe MPE and of non-recent unknown reactions in our patients (74% of all AALs; 63% low risk phenotypes) provides a large sample size to explore further, while the higher use of antibiotics that are the target of antimicrobial stewardship programs (eg, ceftriaxone) in AAL patients provides an impetus for change. The increased use of restricted antibiotics (eg, ceftriaxone and fluoroquinolones) and the reduced use of simple penicillins (eg, flucloxacillin) in patients with an AAL were marked. The effects of AALs on antibiotic prescribing have been described in large hospital cohorts and in specialist subgroups (eg, cancer patients).3,4 Associations between AALs and inferior patient outcomes, higher hospital costs and microbiological resistance have also been recently noted.2–4,8,17,25 Re-examining AALs in older patients from an antimicrobial stewardship viewpoint is therefore essential, particularly in an era when multidrug-resistant (MDR) organisms are being isolated more frequently in Australia.26 The fact that third generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones are associated with MDR organisms and with Clostridium difficile infection generation further supports the need for re-examining AALs, especially in those with easily resolved non-genuine allergies.27–30

The high rate of potential patient acceptance of an oral re-challenge (54%), especially by those with low risk phenotypes (48%), suggests that this should be explored in prospective studies. The idea of an antibiotic allergy re-challenge of low risk phenotypes is a practical extension of the work by Blumenthal and colleagues,24 who found a sevenfold increase in β-lactam uptake and a low rate of adverse reactions. Another group found that oral re-challenge was safe in children with a history of delayed allergy.23 These are both important advances; while skin-prick allergy testing is sensitive for immediate penicillin hypersensitivity, skin testing (delayed intradermal and patch) lacks sensitivity for delayed hypersensitivities.8,22,31 Incident-free accidental re-challenge with the culprit antibiotic or a drug from a similar class had occurred in some of our patients, adding further support for exploring this approach. A structured oral re-challenge strategy is attractive, as skin-prick testing is potentially expensive and inaccessible for most people.8

Analysing the high rate of AAL mismatch may be a more pragmatic low-cost approach, as not only were AAL labels absent from a number of medical records, the EMR AAL often differed from patients’ reports. Incorrect and absent AALs in other centres have been raised as a concern from a drug safety viewpoint.6,7,10 Education programs aimed at improving clinicians’ (pharmacy and medical) understanding of allergy pathogenesis could also assist antibiotic prescribing in the presence of AALs.5,10 Interrogation of the patient and their relatives about allergy history and examination of blood investigations at the time of the ADR for evidence of end organ dysfunction or eosinophilia may also provide greater accuracy in phenotyping and severity assessment. Many accumulated childhood allergies reflect the infectious syndrome that resulted in the implicated antibiotic being prescribed, rather than an immunologically mediated drug hypersensitivity.21,23 Referral to allergy specialists at the time of drug hypersensitivity may also reduce over-labelling.

That a clinician questionnaire about antibiotic prescribing attitudes was not administered is a limitation of this study, as was the inability to obtain AAL information from all patients (eg, because of dementia or delirium) or to further clarify “unknown” reactions. Some AAL descriptions are also likely to be affected by recall bias; however, this reflects real world attitudes and prescribing in the presence of AALs. While the prevalence of AALs in younger patients is probably lower than found in this study, the distribution of genuine, non-genuine and low risk allergies may well be the same. In a group of paediatric patients with an AAL for β-lactam antibiotics following non-immediate mild cutaneous reactions without systemic symptoms, none experienced severe reactions after undergoing oral re-challenge.23

Conclusion

AALs were highly prevalent in our older inpatients, with a significant proportion involving non-genuine allergies (eg, drug side effects) and low risk phenotypes. Most patients were willing to undergo a supervised oral re-challenge if their allergy was deemed low risk. AALs were sometimes associated with inadvertent class re-challenges, facilitated by poor allergy documentation, without ill effect. AALs were also associated with increased prescribing of ceftriaxone and fluoroquinolone, antibiotics commonly restricted by antimicrobial stewardship programs. These findings inform a mandate to assess AALs in the interests of appropriate antibiotic use and drug safety. Prospective studies incorporating AALs into antimicrobial stewardship and clinical practice are required.

Box 1 –

Classification of reported antibiotic allergy labels into adverse drug reaction groups12,13

Box 2 –

Baseline demographics for patients with and without antibiotic allergy labels

|

Characteristic

|

Patients with an antibiotic allergy label

|

Patients with no antibiotic allergy label

|

P

|

|

|

Number

|

107

|

346

|

|

|

Median age [IQR], years

|

82 [74–87]

|

80 [71–88]

|

0.32

|

|

Sex, men*

|

38 (36%)

|

194 (56%)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Immunosuppressed

|

25 (23%)

|

29 (8%)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Median age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index score [IQR]

|

6 [4–7]

|

6 [4–7]

|

0.17

|

|

Ethnicity

|

|

|

0.38

|

|

European

|

106 (99%)

|

334 (97%)

|

|

|

African

|

0

|

2 (1%)

|

|

|

Asian

|

1 (1%)

|

10 (3%)

|

|

|

Infection diagnosis

|

50 (47%)

|

140 (41%)

|

0.25

|

|

Infections (205 patients)

|

56

|

151

|

0.002

|

|

Cardiovascular system

|

0

|

2 (1%)

|

|

|

Central nervous system

|

1 (2%)

|

3 (2%)

|

|

|

Gastrointestinal

|

9 (16%)

|

9 (6%)

|

|

|

Eyes, ears, nose and throat

|

0

|

3 (2%)

|

|

|

Upper respiratory tract

|

7 (13%)

|

30 (20%)

|

|

|

Lower respiratory tract (including pneumonia)

|

12 (21%)

|

54 (36%)

|

|

|

Skin and soft tissue

|

7 (13%)

|

14 (9%)

|

|

|

Urinary system

|

11 (20%)

|

21 (14%)

|

|

|

Pyrexia (no source)

|

3 (5%)

|

4 (3%)

|

|

|

Sepsis (unspecified)

|

5 (9%)

|

8 (5%)

|

|

|

Other

|

0

|

2 (1%)

|

|

|

Received antibiotics

|

45 (42%)

|

162 (46%)

|

0.43

|

|

|

* There were a total of 232 men and 221 women in the study.

|

Box 3 –

Spectrum of implicated antibiotics linked with reported antibiotic allergy labels according to adverse drug reaction classification

|

Implicated antibiotics

|

Antibiotic allergy labels: adverse drug reactions

|

|

Type A

|

Type B

|

Unknown

|

Total

|

|

Type B-I

|

Type B-IV

|

Type B-IV*

|

|

|

All antibiotics

|

27 (17%)

|

26 (16%)

|

29 (18%)

|

16 (10%)

|

62 (39%)

|

160

|

|

Simple penicillins*

|

7 (26%)

|

14 (54%)

|

16 (55%)

|

4 (25%)

|

14 (23%)

|

55 (34%)

|

|

Aminopenicillins†

|

1 (4%)

|

2 (8%)

|

2 (7%)

|

1 (6%)

|

2 (3%)

|

8 (5%)

|

|

Anti-staphylococcal penicillins‡

|

0

|

0

|

1 (3%)

|

5 (31%)

|

3 (5%)

|

9 (6%)

|

|

Cephalosporins

|

3 (11%)

|

1 (4%)

|

1 (3%)

|

2 (13%)

|

11 (18%)

|

18 (11%)

|

|

Carbapenems§

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

1 (2%)

|

1 (0.6%)

|

|

Monobactam

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

0

|

|

Fluoroquinolones

|

2 (7%)

|

0

|

2 (7%)

|

0

|

3 (5%)

|

7 (4%)

|

|

Glycopeptides

|

0

|

0

|

1 (3%)

|

1 (6%)

|

1 (2%)

|

3 (2%)

|

|

Lincosamides

|

0

|

0

|

1 (3%)

|

0

|

2 (3%)

|

3 (2%)

|

|

Tetracyclines

|

4 (15%)

|

1 (4%)

|

0

|

1 (6%)

|

5 (8%)

|

11 (7%)

|

|

Macrolides

|

1 (4%)

|

2 (8%)

|

1 (3%)

|

1 (6%)

|

6 (10%)

|

11 (7%)

|

|

Aminoglycosides

|

0

|

0

|

1 (3%)

|

0

|

0

|

1 (0.6%)

|

|

Sulfonamides¶

|

4 (15%)

|

4 (15%)

|

3 (10%)

|

1 (6%)

|

9 (15%)

|

21 (13%)

|

|

Others

|

5 (19%)

|

2 (8%)

|

0

|

0

|

5 (8%)

|

12 (8%)

|

|

|

All percentages are column percentages, except for the “all antibiotics” row. * Benzylpenicillin, phenoxymethylpenicillin, benzathine penicillin. † Amoxicillin, amoxicillin–clavulanate, ampicillin. ‡ Flucloxacillin, dicloxacillin, piperacillin–tazobactam, ticarcillin–clavulanate. § Meropenem, imipenem, ertapenem. ¶ Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, sulfadiazine.

|

Box 4 –

Antibiotic use in patients with and without an antibiotic allergy label

|

Antibiotic class prescribed

|

Antibiotic prescriptions

|

P

|

|

Antibiotic allergy label group

|

No antibiotic allergy label group

|

|

|

Total number of patients

|

89

|

368

|

|

|

β-Lactam penicillins

|

14 (16%)

|

120 (35%)

|

0.02

|

|

Simple penicillins*

|

4 (5%)

|

32 (9%)

|

0.27

|

|

Aminopenicillins†

|

8 (9%)

|

52 (14%)

|

0.22

|

|

Anti-staphylococcal penicillins‡

|

2 (2%)

|

36 (10%)

|

0.02

|

|

Carbapenems§

|

2 (2%)

|

5 (1%)

|

0.63

|

|

Cephalosporins (first/second generation)

|

8 (9%)

|

20 (5%)

|

0.22

|

|

Cephalosporins (third or later generation)

|

29 (33%)

|

82 (22%)

|

0.05

|

|

Monobactam

|

0

|

0

|

NA

|

|

Fluoroquinolones

|

5 (6%)

|

6 (2%)

|

0.04

|

|

Glycopeptides

|

3 (3%)

|

12 (3%)

|

1

|

|

Tetracyclines

|

6 (7%)

|

46 (13%)

|

0.14

|

|

Lincosamides

|

0

|

0

|

NA

|

|

Others

|

26 (29%)

|

109 (30%)

|

1

|

|

|

NA = not applicable. * Benzylpenicillin, phenoxymethylpenicillin, benzathine penicillin. † Amoxicillin, amoxicillin–clavulanate, ampicillin. ‡ Flucloxacillin, dicloxacillin, piperacillin–tazobactam, ticarcillin–clavulanate. § Meropenem, imipenem, ertapenem. Some patients received more than one antibiotic.

|

Box 5 –

Antibiotic use in patients with penicillin and cephalosporin antibiotic allergy labels

|

|

Patients with documented allergy to penicillins* (n = 70)

|

|

Antibiotics prescribed:

|

|

|

Any antibiotics

|

28 (40%)

|

|

More than one class of antibiotic

|

31 (44%)

|

|

Culprit group penicillins†

|

1 (1.4%)

|

|

Non-culprit group penicillins

|

2 (2.9%)

|

|

First generation cephalosporins

|

4 (5.7%)

|

|

Second generation cephalosporins

|

2 (2.9%)

|

|

Third generation cephalosporins

|

17 (24%)

|

|

Carbapenems

|

2 (2.9%)

|

|

Fluoroquinolones

|

4 (5.7%)

|

|

Glycopeptides

|

2 (2.9%)

|

|

Aminoglycosides

|

2 (2.9%)

|

|

Lincosamides

|

0

|

|

Patients with documented allergy to cephalosporins (n = 18)

|

|

Antibiotics prescribed:

|

|

|

Any antibiotics

|

10 (56%)

|

|

More than one class of antibiotic

|

7 (39%)

|

|

Culprit generation cephalosporins

|

1 (5.6%)

|

|

Non-culprit generation cephalosporins

|

3 (17%)

|

|

Other‡

|

1 (5.6%)

|

|

Any penicillins*

|

5 (28%)

|

|

Carbapenems

|

1 (5.6%)

|

|

Fluoroquinolones

|

1 (5.6%)

|

|

Glycopeptides

|

1 (5.6%)

|

|

Aminoglycosides

|

1 (5.6%)

|

|

Lincosamides

|

0

|

|

|

* Penicillins (benzylpenicillin, phenoxymethylpenicillin, benzathine penicillin); aminopenicillins (amoxicillin, amoxicillin–clavulanate, ampicillin), and anti-staphylococcal penicillins (flucloxacillin, dicloxacillin, ticarcillin–clavulanate and piperacillin–tazobactam). † Prescription of culprit group penicillin: received any penicillin from the same group as that to which the patient is allergic. ‡ This patient had a documented allergy to an unknown generation of cephalosporin, and received ceftriaxone.

|

more_vert

more_vert