Most cases can be diagnosed by good clinical assessment at the bedside

The presence of ascites is a common physical finding and the detection of ascites is important for both diagnostic and prognostic reasons. Ascites is defined as the pathological accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity.1 It may be due to a number of causes (Box 1). The most common is portal hypertension as a result of cirrhosis (> 75%) but malignancy (10%), heart failure (3%) and infection (2%) are other possibilities.1

Patients with ascites usually present to clinicians with increasing abdominal distension, weight gain and discomfort. However, ascites may be detected incidentally in patients developing other complications of their cirrhosis, such as variceal haemorrhage and encephalopathy. Moreover, a patient may present when their underlying heart failure or malignancy progresses.

Initial assessment of the patient will involve taking a history to determine the risk of liver disease. This will include questions about alcohol consumption and risk factors for chronic hepatitis, especially hepatitis C. Cardiac symptoms (shortness of breath and orthopnoea) can be assessed and patients should also be asked about symptoms that might indicate an underlying malignancy, such as weight loss and decreased appetite. Patients who do not complain of ankle swelling or abdominal distension are unlikely to have significant ascites.2

The examination of a patient with ascites includes two main components: inspection and palpation.

General inspection of the patient should include looking for signs of chronic liver disease, such as jaundice, spider naevi, palmar erythema, gynaecomastia and loss of body hair. Prominent collateral veins in the abdominal wall may also be present. Bulging flanks (Box 2) may be due to ascites or obesity, but the absence of this sign makes the presence of ascites unlikely.2

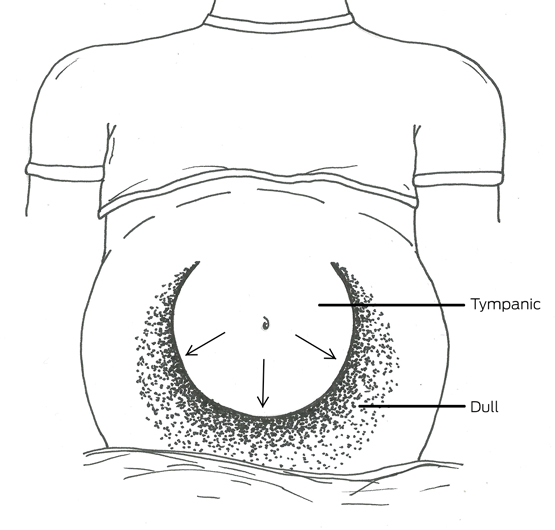

Palpation of significant hepatomegaly and splenomegaly may help the diagnostic process, but can be difficult to perform in a patient with a large volume of ascites or tenderness. With the patient lying supine with their head on a single pillow, there will be a tympanic area to percussion in the midline of the abdomen, which will normally be bordered by an area of dullness in either flank (Box 3). To assess this, the clinician should place their hand in the midline, parallel to the direction of the expected change in resonance, and percuss away from themselves until the percussion note changes from tympanic to dull. It is possible to repeat this manoeuvre in each direction. However, to demonstrate shifting dullness, the clinician will need to ask the patient to roll towards them, and on to the patient’s right side, while keeping their hand on the patient at the location of the dull percussion note. After waiting up to a minute for fluid to shift, the clinician can percuss once again from the tympanic area, which will now be in the flank, to the dull area, which will be in the midline. The sensitivity and specificity of this test for ascites is more than 70%.3

With a significant volume of ascites, it may be possible to elicit a fluid thrill or wave. This may require two people. The second person places the ulnar border of their forearm, or both hands, on the midline of the patient’s abdomen to prevent transmission of the thrill through the subcutaneous fat. The clinician then taps the flank firmly and feels for an impulse on the opposite side. This sign lacks sensitivity but is highly specific.3

Box 4, adapted from a review by Williams and Simel,3 summarises the significant symptoms and signs to consider when evaluating a patient with ascites, and their accuracy and precision. The absence of reported ankle swelling and abdominal distension, combined with no bulging flanks, flank or shifting dullness, are most helpful in excluding ascites. A diagnosis can be positively made when a patient has a fluid thrill together with shifting dullness and ankle swelling. Studies suggest high levels of agreement between clinicians, especially those with experience, on the detection of ascites using these techniques.2,4,5 Using ultrasound or computed tomography, the volume of ascites that can be detected is probably as small as 100 mL. However, it is unlikely that volumes of this magnitude will be detectable on clinical assessment. For flank dullness, more than 1 L of ascitic fluid needs to be present.

The gold standard for detecting ascites is aspiration of fluid after visualisation with imaging.3 However, with good clinical assessment, using the presence of a fluid thrill, shifting dullness and peripheral oedema as the positive indicators, the majority of cases can be diagnosed by a clinician at the bedside.

Box 1 –

Frequency of causes of ascites

|

Frequency |

Cause |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Very common |

Cirrhosis |

||||||||||||||

|

Common |

Right-sided heart failure |

||||||||||||||

|

|

Malignancy |

||||||||||||||

|

Rare |

Tuberculosis |

||||||||||||||

|

|

Pancreatitis |

||||||||||||||

|

|

Nephrotic syndrome |

||||||||||||||

|

Very rare |

Constrictive pericarditis |

||||||||||||||

|

|

Budd–Chiari syndrome |

||||||||||||||

|

|

Protein-losing enteropathy |

||||||||||||||

|

|

Chylous ascites |

||||||||||||||

|

|

Serositis (lupus, familial Mediterranean fever) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 4 –

Significant pooled results for the accuracy of clinical history and physical examination in the detection of ascites*

|

Symptom or sign |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

Likelihood ratio† |

||||||||||||

|

Positive |

Negative |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Abdominal distension |

87% |

77% |

4.2 |

0.2 |

|||||||||||

|

Ankle swelling |

93% |

66% |

2.8 |

0.1 |

|||||||||||

|

Bulging flanks |

81% |

59% |

2.0 |

0.3 |

|||||||||||

|

Flank dullness |

84% |

59% |

2.0 |

0.3 |

|||||||||||

|

Shifting dullness |

77% |

72% |

2.7 |

0.3 |

|||||||||||

|

Fluid thrill |

62% |

90% |

6.0 |

0.4 |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* Adapted from Williams and Simel.3 † The likelihood that a symptom or sign would be expected if a patient had ascites: positive likelihood ratio indicates how much more likely the presence of ascites will be if the sign or symptom is present; negative likelihood ratio indicates how unlikely ascites would be if the symptom or sign were absent. |

|||||||||||||||

more_vert

more_vert