The review by Mark Wilson and colleagues (Dec 19, p 2526)1 provides an excellent overview of pre-hospital emergency medicine. The authors highlight specific considerations both for clinical management and for scene management. We would like to emphasise one key element to complete the review: pain control. Pain control is a good example of how pre-hospital care has evolved in the past years.

Preference: Emergency Medicine

202

[Comment] Offline: Paolo Macchiarini—science in conflict

The resignation of Anders Hamsten as Vice-Chancellor of the Karolinska Institute has accelerated a growing sense of emergency within the Swedish biomedical science community. His departure comes during the same week that the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences issued an unprecedented statement accusing Paolo Macchiarini of “ethically indefensible working methods”. The Academy is the body that awards annual Nobel Prizes in Physics, Chemistry, and Economics (the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded by the Karolinska Institute, hence the likely acute embarrassment at the tarnished reputation of one of the world’s most respected scientific centres).

Hospital funding crisis ‘not our problem’, says Commonwealth

The Commonwealth is on a collision course with the states over health spending after Treasurer Scott Morrison declared the second tier of government was on its own despite a looming $35 billion funding gap.

As the nation’s treasurers prepare to meet next month, Mr Morrison has told his State and Territory counterparts that there would be no extra funding from the Commonwealth.

“We all have to manage our budgets,” he told the National Press Club. “Asking for buckets of money doesn’t solve your expenditure problem.”

Several states have been pushing for tax reform, including a bigger slice of the Commonwealth’s tax take, because of a looming shortfall in funding for hospitals and schools.

Changes unveiled in the 2014-15 Budget that are due to come into effect next year are expected to strip $57 billion from public hospital funding revenue over 10 years, creating what AMA President Professor Brian Owler said was “funding black hole” that would have dire consequences for patients.

“Public hospital funding is about to become the single biggest challenge facing State and Territory finances,” Professor Owler said. “Without sufficient funding to increase capacity, public hospitals will never meet the targets set by governments, and patients will wait longer for treatment.”

The AMA’s annual Public Hospital Report Card showed that performance improvements have stalled and, in some instances, are going into reverse, as hospitals struggle with inadequate funding.

Almost a third of Emergency Department patients categorised as urgent are waiting more than 30 minutes for treatment, and elective surgery patients are, on average, waiting six days longer than they were a decade ago.

There had been hopes that Federal, State and Territory leaders would agree on tax changes at a meeting to discuss reform of the Federation next month that would put health funding on a firmer financial footing.

But the likelihood of the meeting appears to be rapidly receding after Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull ruled out any changes to the GST, which was at the centre of reform plans advanced by several states, including South Australia and New South Wales.

Instead, the Commonwealth appears determined to divest itself as much as possible of responsibility for health funding.

Mr Turnbull said the Federal Government did not want to increase the total tax take “in net terms”, and challenged the states to find their own sources of extra funds for health.

Papers prepared for the Council of Australian Governments meeting in December indicated that the Commonwealth and the states faced a combined health funding gap of $35 billion by 2030, and suggested closing it would require both spending restraint and an increase in tax revenue.

[Comment] Zika virus and microcephaly: why is this situation a PHEIC?

When the Director-General of WHO declared, on Feb 1, 2016, that recently reported clusters of microcephaly and other neurological disorders are a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC),1 it was on the advice of an Emergency Committee of the International Health Regulations and of other experts whom she had previously consulted. We are the members of the Emergency Committee, and we were identified by the Director-General from rosters of experts that had been submitted by WHO Member States.

[Comment] A crucial time for public health preparedness: Zika virus and the 2016 Olympics, Umrah, and Hajj

The 138th session of WHO’s Executive Board on Jan 25, 2016, noted both the end of the 2014 Ebola crisis and the beginning of a global public health threat, the outbreak of Zika virus infection in the Americas.1 On Jan 15, 2016, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advised pregnant women to refrain from travelling to countries affected by Zika, given a possible association between Zika virus infection with microcephaly and other neurological disorders.2 On Feb 1, 2016, WHO’s International Health Regulations Emergency Committee declared the possible association between Zika virus infection and clusters of microcephaly and other neurological disorders as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.

Birth defect fears deepen as Zika spreads

Evidence linking the rapidly spreading Zika virus to birth defects is mounting, adding to the urgency of efforts to develop a vaccine and underlining calls for co-ordinated international efforts to control its spread.

A recent spate of microcephaly cases involving women who were infected with Zika while pregnant – including one where the virus was found in a newborn’s brain tissue – has strengthened suspicions the disease is responsible for severe abnormalities.

Thirty-four countries have been hit so far in the current outbreak, most of them in Latin America, according to the World Health Organisation. In Brazil alone, around 1.5 million cases have been reported, and a further 25,000 are suspected in Colombia.

But the disease has also spread to the Pacific. Ongoing transmission has been reported in Tonga, where 542 suspected cases have been identified, and Samoa.

Though there is no evidence of Zika virus transmission in Australia, Chief Medical Officer Professor Chris Baggoley has warned there is a “continuing risk” of the disease being imported into the country from infected areas – so far this year, seven cases have been confirmed, all involving returning travellers.

Disturbingly, two pregnant women who recently travelled to Zika-prone regions have tested positive to the virus – one if Victoria, the other in Queensland.

Health authorities have convened a Communicable Disease Network Australian working group to monitor the international outbreak and advise on public health measures.

Though the effects of the disease are considered relatively mild in adults, the WHO has declared the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern because of mounting fears it is causing serious birth defects.

WHO Director-General Dr Margaret Chan said last week that although a causal relationship between Zika virus infection in pregnancy and microcephaly (babies born with abnormally small heads) was not yet scientifically proven, it was “strongly suspected”.

Evidence of a causative link between the virus and severe congenital abnormalities is strengthening.

Last month, a mother in Hawaii who was infected with the Zika virus during her pregnancy gave birth to a baby with microcephaly, and the US Centers for Disease Control reported on 10 February the Zika infection was evident in the case of two babies born with microcephaly who subsequently died, and two instances of miscarriage. In addition, the New England Journal of Medicine reported the case of a Slovenian woman who suffered a Zika-like illness while pregnant in Brazil. Her baby developed microcephaly, and the Zika virus was found in its brain tissue.

“The level of alarm is extremely high,” Dr Chan said. “Arrival of the virus in some places has been associated with a steep increase in the birth of babies with abnormally small heads and in cases of Guillain-Barre syndrome.”

In declaring a health emergency, the WHO has urged a coordinated international response to the virus threat, including improved surveillance of infections and the detection of congenital malformations, intensified mosquito control measures, and the expedited development of diagnostic tests and vaccines.

There is currently no treatment or immunisation for Zika, and although 15 companies or groups are working on a vaccine, the WHO has warned it is likely to be 18 months before one is ready for trial.

Their task is complicated by uncertainty about how the virus is spread. Though mosquitos are considered the prime culprit, there are suspicions it may also be spread though bodily fluids, particularly blood and semen.

As a precaution, the Australian Red Cross Blood Service has deferred collecting blood from donors who have travelled to countries with mosquito-borne viruses such as dengue and malaria.

The virus, which is closely related to the dengue virus, was first detected in 1947, and since 2012 there have only been 30 confirmed cases in Australia, all of them involving infection acquired overseas.

Members of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases have warned that the next stage of the epidemic may involve the re-emergence of Zika in sub-Saharan Africa and, from there, southern Europe.

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade has advised pregnant women considering travelling to countries where the Zika virus is present to defer their plans.

All other travellers are advised to take precautions to avoid being bitten by mosquitos, including wearing repellent, wearing long sleeves, and using buildings equipped with insect screens and air conditioning.

Adrian Rollins

Gender diversity matters

2015 was perhaps a seminal year for the issue of gender inequity in the medical profession.

The year started with comments about sexual harassment in surgery.

To its credit, the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons resisted the urge to deny there was a problem, and instead commissioned an independent Expert Advisory Group (EAG) to investigate its extent. The Group’s report gave a sobering picture of the high prevalence of bullying, discrimination, and sexual harassment in the surgical workforce. I have no doubt that there are implications for the wider medical profession.

It was pleasing that the EAG responded to a number of points put forward by the AMA in its submission, including recognising that commitment to change needs to come from the top, and the importance of increasing gender diversity in senior roles in the College.

A scan of the leadership across the colleges, societies and employers shows limited gender diversity. My own college, the Australasian College for Emergency Medicine, is a case in point – currently, there are no women on its board. This under-representation exists despite the dramatic increase in female participation in the medical workforce in recent decades, to the extent that women now outnumber men as graduates of Australian medical schools.

To be sure, the medical profession is not alone in having a small number of women in senior leadership and management roles. According to the Australian Government’s Workplace Gender Equality Agency, last year only 9.2 per cent of ASX 500 company directors were women; they comprised 9.2 per cent of ASX 500 executive management personnel; and 23 per cent of Australian university vice-chancellors.

Why does this matter?

A healthier gender balance is essential if the medical profession is to harness the potential of all its members, and reflect the realities of modern medicine in policy and practice.

Like many, I believe that determined leadership is the key to accomplishing lasting change in the culture of our profession. This includes the upper tiers of the colleges and associations, the employers of doctors and, indeed, the AMA itself.

At times the pace of change may seem slow, and the task too difficult; however, the changes that have been demonstrated recently within the culture of the Australian Army show what can be achieved with a determined effort.

There has been considerable debate, and no consensus, as to whether an increase in gender diversity is best accomplished by using mandated targets or quotas. In our submission to the EAG, the AMA expressed support for a voluntary code of practice or a similar document, that includes voluntary targets and timeframes.

I believe this approach is worthy of consideration.

Our goal is clear – to achieve timely and substantial progress towards a leadership of the medical profession that reflects its composition. In turn, we are then more likely to realise the full potential of our abilities as doctors, and to promote a healthier professional culture.

Factors contributing to frequent attendance to the emergency department of a remote Northern Territory hospital

Katherine Hospital services a very large (340 000 km2) and remote tropical region in northern Australia. The population of the region (20 000 people, 51% of whom are Aboriginal) is centred on the town of Katherine, 320 km southeast of Darwin.

As with all hospitals, frequent attenders (FAs) to the emergency department (ED) represent a significant proportion of the acute care workload. Local and international medical literature has defined FAs as patients who present to an ED between four and six times within a year;1,2 associations with homelessness, poverty, alcohol misuse and chronic illness have been documented.3–7 This literature, however, is predominantly focused on urban and non-tropical environments, and problems specific to northern Australian hospitals have not been investigated.

Severe and chronic homelessness is a major problem for Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory. It is closely coupled with social determinants of health and complicated by the harsh and remote environment. More than 7% of Aboriginal people in the region are considered homeless, a rate that is about 15 times the national average.8 Services for homeless people in the region are limited, in terms of both crisis and longer term accommodation, as well as with regard to access to food and hygiene facilities.

There is evidence that ED-based social interventions for FAs and homeless people, including providing housing and case management, reduce the number of presentations to EDs.9–11 Australian research suggests that providing specific non-emergency interventions targeted at FAs can reduce the burden of overcrowding for EDs.12

We aimed to identify factors, unrelated to chronic health problems, that contribute to frequent presentation to Katherine Hospital, which serves a young Aboriginal population with very high rates of homelessness, significant burdens of disease associated with poverty and poor housing, and limited access to services that provide safe housing.

Methods

Study design and setting

We performed a non-matched case–control study that included all adult patients who presented to Katherine Hospital ED between 1 January and 31 December 2012. During this period, a total of 8340 people were seen in 14 895 separate ED presentations. Ethics approval for the study was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Menzies School of Health Research (reference, 2013-2096).

Selection of cases and controls

The required case sample size for the study was calculated as being 137 patients; this was adequate to detect an effect size yielding an odds ratio (OR) of at least 2.0 with α = 0.05 and a power of 0.8.

The electronic patient database (Caresys) was used to identify all patients presenting to the ED during 2012. Cases were defined as those with six or more presentations during that period. A single presentation episode was randomly selected from all the presentations by an FA, and clinical and non-clinical data were extracted from the hospital electronic records for that single presentation.

The study excluded those with chronic health problems associated with a predictable need for multiple presentations. Exclusion criteria included patients needing peritoneal or haemodialysis, ambulatory care (including wound dressings, follow-up of test results, medication administration, and device management), obstetric patients, and those with chronic severe health conditions resulting in end-stage renal, hepatic, cardiac, respiratory or endocrine dysfunction or active malignancy.

We restricted our sample to residents of the NT to reduce a possible bias in the control population (high frequency of tourists during the dry season). As our focus was the adult population, we also excluded patients under the age of 18 years.

Unmatched controls were randomly selected (1:1) from the 5376 individuals who presented to the Katherine Hospital ED only once during the study period and who did not meet the exclusion criteria. Controls were not matched to cases, as we aimed to compare all differences in environmental, demographic and social variables between the two groups.

Ascertainment of risk factors and exposures

Patient data collected included age, sex, Indigenous status, alcohol intake and violence relevant to the presentation, triage score, discharge destination (admitted to ward or discharged from ED), and medical diagnosis (International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, Australian modification [ICD-10-AM] categories). Records were linked with hospital mortality data, which were available to January 2015.

Living arrangements were classified as residential, homeless, or out-of-town; the last category included people visiting Katherine, predominantly from remote communities in the region, but also visitors from other NT towns.

Historical weather data were obtained from the Australian Bureau of Meteorology: rainfall (mm) on the day of presentation, and during the preceding 7 and 30 days, and minimum and maximum temperatures on the day of presentation. For analysis, the data were coded as dichotomous variables: rainy day (yes v no), minimum temperature under 12°C (yes v no) and maximum temperature over 38°C (yes v no).

Analysis

We performed our analysis with Stata 13.0 (StataCorp). We used simple unpaired two-sided t tests (continuous data) and χ2 tests (categorical data) to compare differences in exposures for the case and control groups. Fisher exact tests were used to compare triage categorisation in the two groups. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. We performed individual, unadjusted logistic regression analyses of each social and weather variable to assess the association between each exposure and subsequent admission to hospital and the likelihood of frequent presentation to the Katherine Hospital ED. Interactions between individual variables were tested by regression analysis.

A backwards stepwise logistic regression model was used to identify factors that predicted frequent presentation to the Katherine Hospital ED; the individual significance of each variable to be included in the model was set at P < 0.20.

Results

A total of 227 individuals were classified as FAs; they made 1948 ED presentations, or 13% of all ED presentations for the year. Ninety FAs met our exclusion criteria, leaving 137 cases for the study. The number of presentations by each FA during the 12 months ranged between six (47 patients) and 27 (1 patient), with the distribution skewed to the lower end of the distribution. A total of 137 FA cases and 136 controls were included in the study.

The age and sex characteristics of the FAs and controls were similar (Box 1). There was a statistically significant difference between groups in terms of homelessness (OR, 16.44; P < 0.001) and unstable living conditions (homeless or out-of-town) (OR, 3.02; P < 0.001). The proportion of individuals who identified as Aboriginal also differed between the two groups (OR, 2.16; P < 0.001), as did the proportion of presentations in which alcohol use was involved (OR, 2.77, P = 0.001). Although presentations by 15.3% of FAs involved violence, compared with 10.1% in the control group, this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.189).

The type of clinical presentation as defined by the presenting complaint was somewhat heterogeneous, with different patterns for FAs and controls (Box 2). Triage classification was statistically different between the two groups (P = 0.004). While there were more category 1 presentations by controls (nine controls v one case), there were also more category 4 presentations (94 controls v 79 cases); there were more category 3 presentations by FA compared to controls (41 cases v 23 controls) (Box 1). Two-year mortality in the case group was 7.3% (ten deaths) and 2.8% (four deaths) in the control group; this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.094).

FAs were more likely than controls to be admitted to hospital as a result of their presentation, although the difference was not statistically significant (OR, 1.63; P = 0.09). Aboriginal people (P = 0.004) and those who were homeless or had insecure housing (P = 0.04) were significantly more likely to be admitted. There was no association between admission status and cold weather, but patients in both groups were more likely to be admitted during hot weather (P = 0.007). There was no difference between groups with respect to temperature or rainfall on the day of attendance.

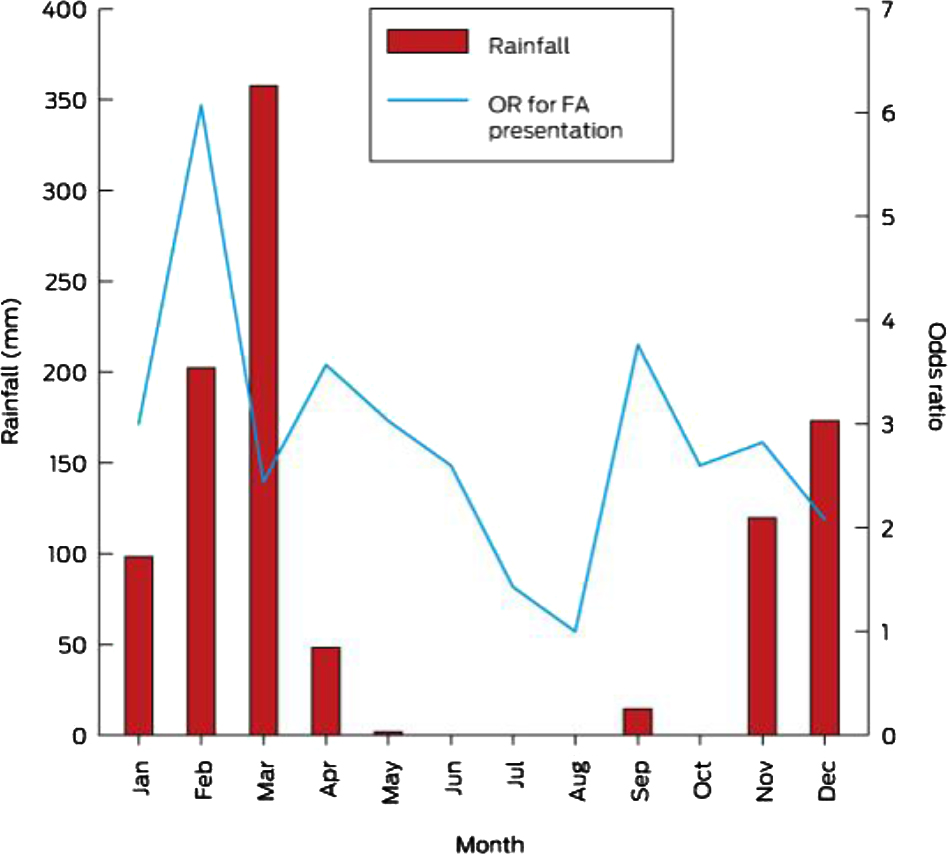

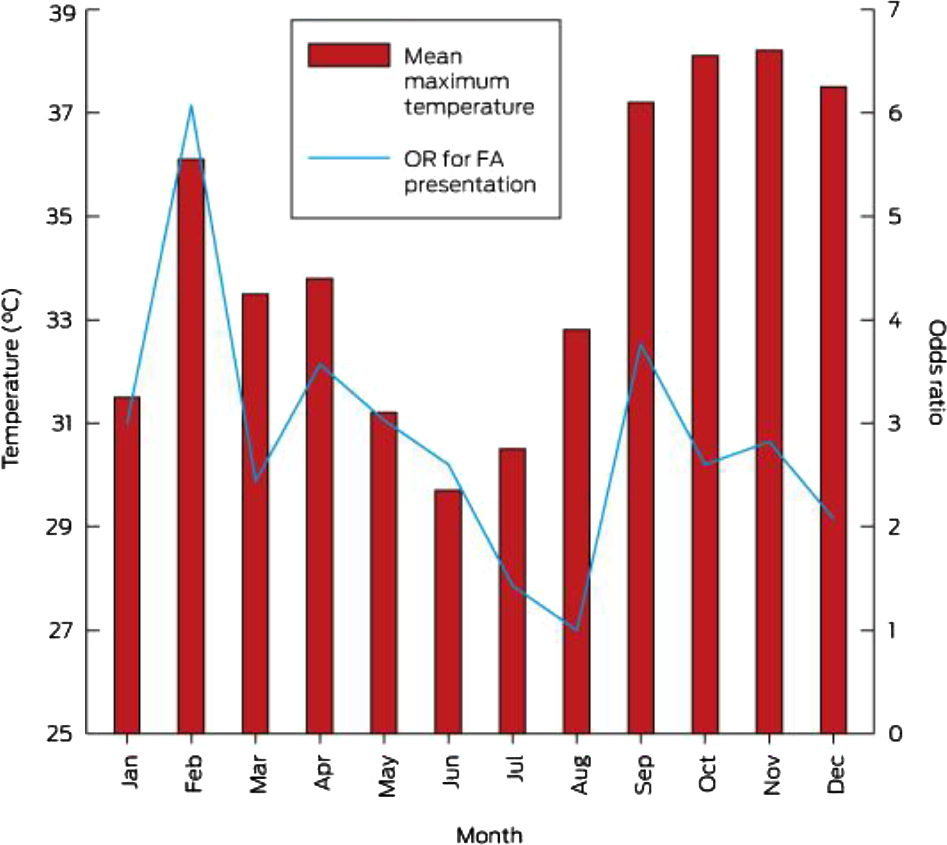

The results of unadjusted logistic regression analysis of social variables were consistent with these findings. Alcohol was more likely to be involved in presentations by FAs (OR, 2.84; P = 0.002); FAs were more likely to identify as Aboriginal (OR, 3.93; P < 0.001), and to be homeless (OR, 20.4; P < 0.001) or from out of town (OR, 1.95; P = 0.019). There were no statistically significant differences between cases and controls for age, sex or the involvement of violence. Unadjusted logistic regression analysis of annual weather variables (baseline: August, in the dry season) indicated that presentations by FAs were particularly frequent in February (OR, 6.07; P = 0.012). Frequent presentation was more likely during the hot and wet season and on rainy days, but neither association was statistically significant (Box 3, Box 4).

There were no statistically significant interactions between the number of rainy days, homelessness, Indigenous status, and alcohol involved in presentation with respect to frequent presentation. Compared with FAs who had secure housing, FAs who were homeless presented more frequently on a rainy day (OR, 31.7; P = 0.001) than did those who were from out of town (OR, 2.3; P = 0.009), although no statistically significant interaction between the two variables was identified. For FAs there were no statistically significant interactions between rainy day and Indigenous status, rainy day and alcohol contributing to presentation, Indigenous status and alcohol, or homelessness and alcohol.

Backwards stepwise logistic regression indicated that the following variables predicted frequent presentation: Aboriginal status, alcohol use as contributing factor, homelessness, and rainfall on the day of presentation (pseudo-R2 = 0.18; P < 0.001) (Box 5). When tested independently, alcohol use was positively associated with frequent presentation (OR, 2.84; P = 0.002); however, in the regression model this association was attenuated by the joint inclusion of alcohol and Aboriginal status (OR, 1.54; P = 0.238), joint inclusion of alcohol and homelessness (OR, 1.05; P = 0.92); the association was reversed when homelessness and Aboriginal status were both included (OR, 0.47; P = 0.155). None of these findings were statistically significant.

Discussion

This is the first robustly designed case–control study to have clearly defined a group of FAs to a hospital ED without a unifying clinical reason for their frequent presentations. For each FA, we randomly selected a single instance from their presentations over a 12-month period, and compared their clinical and non-clinical variables with those of a control group. This rigorous study design minimised the possibility of confounding and bias, and provided clear insights into reasons for frequent presentations to the hospital by certain individuals. It is also the first study to examine the problems associated with FAs in a tropical Australian region with a large Aboriginal population.

Our study identified a very strong association between frequent ED attendance and each of homelessness and Aboriginal identity, and also a strong association with alcohol (but not violence) as a contributor to the presentation. It is not surprising that being Aboriginal was predictive of frequent presentation, as this group is overwhelmingly affected by homelessness, an association clearly identified as a predictor of frequent attendance by previous studies.2–8

Our results also confirm that presentations by FAs are for genuine acute clinical reasons; although the pattern of triage categories differed between the case and control groups, diagnoses at presentation and rates of admission to hospital were similar. FAs present to ED with genuine clinical needs.

Alcohol is a significant contributor to morbidity and mortality among FAs. However, the effect of the role of alcohol in contributing to the presentation disappeared when both homelessness and Aboriginal status were included in the regression analysis model. This implies that FAs presenting to the ED who are neither Aboriginal nor homeless may have a higher burden of alcohol-related harm than Aboriginal or homeless FAs, who undoubtedly also suffer alcohol-related harm. Further statistical exploration of this phenomenon revealed that the change in the shape of association with frequent attendance was mainly explained by the interaction between alcohol use and homelessness.

The predictive value of weather is more complex. The tropical weather of the Top End of the NT is extreme: the build-up season from October to December, characterised by very hot and humid weather; monsoonal rains from January to March; and the dry season from April to September.

Logistic regression analysis indicated that the effect of the only weather variable predictive of frequent presentation (rain) was only weak. There was a statistically significant spike in presentations by FAs during February, a particularly hot and wet time of the year. It is possible that such weather leads to homeless people attending hospital for shelter, although studies from non-tropical areas have not found such an association.13 It is more likely, particularly given that admission rates for both cases and controls were higher during hotter months, that tropical weather contributes to acute illness that leads to presentation, consistent with local and international research in whole populations.14,15

FAs were responsible for 13% of all ED presentations to this hospital. As these presentations were for genuine emergency medical care, the reasons for an annual death rate among FAs not meeting the exclusion criteria for our study that was 6.8 times as high as the national average16 need to be understood. Although the difference between mortality rates for cases and controls in our small study did not achieve statistical significance, it is likely that FAs have higher age-adjusted mortality rates. Further research is needed to confirm this, and interventions that target the root causes of poor health outcomes for FAs should be offered and evaluated. This includes hospitals recognising the unmet needs of FAs, ensuring that treatable medical problems are diagnosed, and mitigating social and other risks during presentation to an ED.

As a result of our study, Katherine Hospital is instituting a targeted intervention for FAs. Patients presenting to the ED on more than five occasions in the past year will trigger a Frequent Presenter Pathway, with pre-discharge review by an FA team, in which social, medical, and drug and alcohol problems will be identified and addressed.

Limitations to our study include the fact that there were only small numbers of FAs at this hospital, limiting the capacity to detect statistically significant interactions between the analysed characteristics. This study also excluded FAs with chronic health conditions, whose clinical presentations and outcomes are probably different but no less valid than those of the patients in this study. This study did not examine all the variables likely to contribute to frequent attendance, including social and cultural variables (such as events causing remote residents to visit town), access to motor vehicles, financial influences (such as welfare and royalty payments), and environmental variables other than weather (such as bushfire smoke). Clinical data were collected from the patients’ electronic records, and these may not have been complete. True rates of homelessness have probably been under-estimated in this study, as our estimate is based on hospital data that do not include definitions of overcrowded housing and other factors contributing to accommodation instability.

Homelessness in the NT is often referred to as “long-grassing”. This term subtly implies that homelessness is a cultural or lifestyle choice, but there is really no choice involved in the situations in which these people find themselves. The term suggests that homelessness is a contemporary cultural norm for Aboriginal people in the NT. There are a core group of chronically homeless people in fringe-dwelling communities with poor access to services. Many remote Aboriginal people visiting town for social and other needs find themselves temporarily homeless. Adding to this complex situation in other parts of northern Australia is a push to defund and effectively close remote Aboriginal communities, actions that could acutely worsen the situation. The core problem is a lack of housing and accommodation options for rural and remote Aboriginal people.

For towns where homelessness and alcohol misuse are as pervasive as in the Katherine region, there is an ongoing need to redress the root problems by implementing evidence-based alcohol harm minimisation strategies,17 establishing innovative facilities for homeless people that deliver the necessary hygiene and basic environmental protection, and providing greater access to appropriate accommodation. Such measures could reduce the burden of acute presentations to local hospitals, and improve their dignity, so that homeless Aboriginal people may possibly begin to heal.

Box 1 –

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the cases (frequent presenters) and controls

|

|

Frequent attenders |

Controls |

P |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Number of patients |

137 |

136 |

|

||||||||||||

|

Age, years |

42.9 (SD, 15.2) |

40.8 (SD, 16.7) |

0.295 |

||||||||||||

|

Sex (female) |

57.7% |

52.2% |

0.272 |

||||||||||||

|

Aboriginal |

70.8% |

53.0% |

< 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

Living arrangements |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Unstable (homeless or out-of-town) |

48.1% |

23.7% |

< 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

Homeless |

19.7% |

1.4% |

< 0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

Alcohol as contributing factor |

25.6% |

10.8% |

0.001 |

||||||||||||

|

Violence as contributing factor |

15.3% |

10.1% |

0.189 |

||||||||||||

|

Triage category |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

1 |

1 |

9 |

0.004 |

||||||||||||

|

2 |

7 |

7 |

|

||||||||||||

|

3 |

41 |

23 |

|

||||||||||||

|

4 |

79 |

94 |

|

||||||||||||

|

5 |

9 |

3 |

|

||||||||||||

|

Mortality at 2 years |

7.3% |

2.9% |

0.094 |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

SD = standard deviation. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 –

Presentation diagnoses for 137 frequent attenders and 136 controls

|

Presentation diagnosis |

Frequent attenders |

Controls |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Cardiology (chest pain, arrhythmia) |

9 |

9 |

|||||||||||||

|

Endocrinology (diabetes) |

1 |

0 |

|||||||||||||

|

Ear/nose/throat and eye (eye injury or symptom, tonsillitis, otitis externa or interna) |

7 |

10 |

|||||||||||||

|

Gastrointestinal (diarrhoea/vomiting, pancreatitis, gastrointestinal bleed, gastroenteritis, hepatitis) |

7 |

5 |

|||||||||||||

|

Infection (undifferentiated infection, cellulitis) |

10 |

8 |

|||||||||||||

|

Neurology (stroke, dizziness, headache, seizure: including in contact of alcohol) |

10 |

7 |

|||||||||||||

|

Pain (as predominant complaint; diagnosis unclear) |

30 |

39 |

|||||||||||||

|

Psychiatric (not including intoxication) |

3 |

0 |

|||||||||||||

|

Respiratory (asthma, chest infection, shortness of breath) |

19 |

12 |

|||||||||||||

|

Surgical (appendicitis, abscess, foreign body; not eye) |

1 |

2 |

|||||||||||||

|

Trauma and assault |

9 |

13 |

|||||||||||||

|

Urological or renal (urinary tract infection, pyelonephritis, renal calculi, retention) |

2 |

5 |

|||||||||||||

|

Wound |

12 |

5 |

|||||||||||||

|

Alcohol intoxication (as the sole reason for presentation) |

7 |

4 |

|||||||||||||

|

Other (social reasons, medical certificates, other non-medical reasons) |

10 |

17 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 –

Odds ratio for presentation to the emergency department of Katherine Hospital by frequent attenders, by month, compared with monthly rainfall data*

* Reference month for odds ratios is August.

Box 4 –

Odds ratio for presentation to the emergency department of Katherine Hospital by frequent attenders, by month, compared with monthly temperature data*

* Reference month for odds ratios is August.

Box 5 –

Backwards stepwise logistic regression of frequent presenters to the emergency department of Katherine Hospital

|

Presentation characteristics |

Odds ratio (95% CI) |

P |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Aboriginal |

2.06 (1.41–2.84) |

< 0.001 |

|||||||||||||

|

Alcohol involved in presentation |

0.46 (0.16–1.34) |

0.154 |

|||||||||||||

|

Homeless |

14.17 (2.98–67.43) |

0.001 |

|||||||||||||

|

Rain on day |

1.55 (0.78–3.07) |

0.212 |

|||||||||||||

|

Constant |

0.37 (0.23–0.58) |

0.001 |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Model: Frequent attender = 0.37 + 2.01(Aboriginal) + 0.46(alcohol) + 14.17(homeless) + 1.55(rain on day). Model statistics: likelihood ratio (χ2[4] = 50.51; overall probability, P < 0.001; pseudo-R2 = 0.18. |

|||||||||||||||

Invitation for nominations for election to Federal Council

AREA NOMINEES

Invitation for nominations for election to Federal Council as Area Nominees

The Constitution of Australian Medical Association Limited (AMA) provides for the election, every two years, to the Federal Council of one Ordinary Member as a

Nominee of each of the following Areas:

1. New South Wales and Australian Capital Territory Area

2. Queensland Area

3. South Australia and Northern Territory Area

4. Tasmania Area

5. Victoria Area

6. Western Australia Area

The current term of Area Nominee Councillors expires at the end of the AMA National Conference in May 2016.

Nominations are now invited for election as the Nominee for each of the Areas listed above.

1. Nominees elected to these positions will hold office until the conclusion of the May 2018 AMA National Conference. • 2. The nominee must be an Ordinary Member of the AMA and a member in the relevant Area for which the nomination is made. • 3. The nomination must include the name and address of the nominee and the date of nomination. It may also include details of academic qualifications, the nominee’s career and details of membership of other relevant organisations. • 4. Each nomination must be signed by the Ordinary Member nominated AND must be signed by two other Ordinary Members of the AMA resident in the Area for which the nomination is made. • 5. Nominations must be emailed to the Secretary General (atrimmer@ama.com.au). To be valid nominations must be received no later than 1.00pm (AEDT) Friday 4 March 2016. • 6. A nomination may be accompanied by a statement by the nominee of not more than 250 words to be circulated to voters. • 7. The ballot will by undertaken by electronic ballot.

The nomination form can be downloaded from: ama.com.au/system/files/AreaNomineeForm.pdf.

For enquiries please contact Lauren McDougall, Office of the Secretary General and President (email: lmcdougall@ama.com.au).

SPECIALTY GROUP NOMINEES

Invitation for nominations for election to Federal Council as Specialty Group Nominees

The Constitution of Australian Medical Association Limited (AMA) provides for the election, every two years, to the Federal Council of one Ordinary Member as a

Nominee of each of the following Specialty Groups:

1. Anaesthetists 2. Dermatologists 3. Emergency Physicians 4. General Practitioners 5. Obstetricians and Gynaecologists 6. Ophthalmologists 7. Orthopaedic Surgeons 8. Paediatricians 9. Pathologists 10. Physicians 11. Psychiatrists 12. Radiologists 13. Surgeons

The current term of Specialty Group Councillors expires at the end of the AMA National Conference in May 2016.

Nominations are now invited for election as the Nominee for each of the Specialty Groups listed above.

1. Nominees elected to these positions will hold office until the conclusion of the May 2018 AMA National Conference. • 2. The nominee must be an Ordinary Member of the AMA and a member of the relevant Specialty Group for which the nomination is made. • 3. The nomination must include the name and address of the nominee and the date of nomination. It may also include details of academic qualifications, the nominee’s career and details of membership of other relevant organisations. • 4. Each nomination must be signed by the Ordinary Member nominated AND must be signed by two other Ordinary Members of the AMA Specialty Group for which the nomination is made. • 5. Nominations must be emailed to the Secretary General (atrimmer@ ama.com.au). To be valid nominations must be received no later than 1.00pm (AEDT) Friday 4 March 2016. • 6. A nomination may be accompanied by a statement by the nominee of not more than 250 words to be circulated to voters. • 7. The ballot will by undertaken by electronic ballot.

The nomination form can be downloaded from: ama.com.au/system/files/SpecialtyGroupForm.pdf.

For enquiries please contact Lauren McDougall, Office of the Secretary General and President (email: lmcdougall@ama.com.au).

SPECIAL INTEREST GROUP NOMINEES

Invitation for nominations for election to Federal Council as Special Interest Group Nominees

The Constitution of Australian Medical Association Limited (AMA) provides for the election, every two years, to the Federal Council of one Ordinary Member as a Nominee of each of the following Special Interest Groups:

1. Public Hospital Practice (previously called Salaried Doctors)

2. Rural Doctors

3. Doctors in Training

4. Private Specialist Practice.

The term of Councillors expires at the end of the AMA National Conference in May 2016.

Nominations are now invited for election as the Nominee for each of the Special Interest Groups listed above.

1. Nominees elected to these positions will hold office until the conclusion of the May 2018 AMA National Conference. • 2. The nominee must be an Ordinary Member of the AMA and a member of the relevant Special Interest Group for which the nomination is made. • 3. The nomination must include the name and address of the nominee and the date of nomination. It may also include details of academic qualifications, the nominee’s career and details of membership of other relevant organisations. • 4. Each nomination must be signed by the Ordinary Member nominated AND must be signed by two other Ordinary Members of the AMA Special Interest Group for which the nomination is made. • 5. Nominations must be emailed to the Secretary General (atrimmer@ ama.com.au). To be valid nominations must be received no later than 1.00pm (AEDT) Friday 4 March 2016. • 6. A nomination may be accompanied by a statement by the nominee of not more than 250 words to be circulated to voters. • 7. The ballot will by undertaken by electronic ballot.

The nomination form can be downloaded from: ama.com.au/system/files/SIGForm.pdf.

For enquiries please contact Lauren McDougall, Office of the Secretary General and President (email: lmcdougall@ama.com.au).

Australian Medical Association Limited • ABN 37 008 426 793

[Correspondence] Frailty in emergency departments

Population ageing is placing a heavy demand on health-care systems worldwide. This pressure is being particularly felt by hospital emergency departments, which are facing an unprecedented influx of older patients (65 years and older).1 Of concern, more than half of these older patients are likely to be frail.2 Frailty signifies an increased vulnerability to external stressors and has been purported to be the largest global problem associated with an ageing population.3

more_vert

more_vert