Trevor Duke’s Comment (Feb 20, p 721) on the WHO guidelines for emergency triage assessment and treatment is crucial to the proper discovery of shock during the triage process in children.1 Cold extremities, a weak and rapid pulse, and slow capillary refill remain the most sensitive signs for hypovolaemia when one is rapidly decoding a child’s vital signs. However, in practice, the uninitiated triage team can become delayed and often confused by what momentarily seems to be a respectable systolic blood pressure.

Preference: Emergency Medicine

202

[Comment] Yellow fever: the resurgence of a forgotten disease

The possibility that a mosquito bite during pregnancy could cause severe brain damage in newborn babies has alarmed the public and astonished scientists. The Zika outbreak in the Americas shows how a disease that slumbered for six decades in Africa and Asia, never causing an outbreak, can become a global health emergency. The Ebola and Zika outbreaks have revealed gaping holes in our lines of defence: weak health infrastructures and capacities in west Africa and the demise of programmes for mosquito control in the Americas.

Nothing neat about lives put at risk

Patient lives are being put at risk by cuts to a program that was working to reduce deaths among emergency department patients, AMA Vice President Dr Stephen Parnis has warned.

As the pressure mounts on the major political parties to detail their plans for public hospital funding, Dr Parnis – who is an emergency physician – has called for both the Coalition and Labor to commit to specific Commonwealth funding for the National Emergency Access Target (NEAT).

His call follows the publication of a peer-reviewed study published in the Medical Journal of Australia that linked the NEAT with lower in-hospital mortality rates for emergency patients.

When NEAT was introduced, the goal was to ensure that, by 2015, 90 per cent of ED patients were to be admitted, discharged or transferred within four hours. This goal was supported by specific Commonwealth funding.

The MJA study found the policy was working, concluding that “as NEAT compliance rates increased, in-hospital mortality of emergency admissions declined”.

But the Abbott Government axed funding for the program in the 2014-15 Budget, and Dr Parnis said improvements in hospital performance had since stalled.

After improving every year since 2011-12, performance against the NEAT at the national level had “now plateaued, with no further improvements in 2014-15, with the likelihood that the situation could deteriorate as a result of the Budget cuts,” he said.

“A target that was working to improve performance has stopped delivering further improvements.”

The cut the NEAT fund was part of a broader Government policy to slash up to $57 billion from public hospital funding by the mid-2020s by disowning National Health Reform Agreement commitments and lowering the indexation of funding to inflation plus population growth.

The AMA has been highly critical of the massive funding cut, which has also drawn the ire of State and Territory governments.

In an effort to neutralise public hospitals as an election issue, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull last month announced the Commonwealth would inject an extra $2.9 billion into the public hospital system over the next three years.

But Dr Parnis said that although the extra money was welcome, it was “clearly inadequate” in enabling hospitals to meet the needs of patients in the long term.

“The MJA article is further evidence that arbitrary public hospital funding cuts have real consequences for patient mortality,” he said.

Adrian Rollins

[Comment] Microcephaly and Zika virus infection

Rarely have scientists engaged with a new research agenda with such a sense of urgency and from such a small knowledge base as in the current epidemic of microcephaly (6000 notified suspected cases in Brazil1 and the first case detected in Colombia in March, 20162) associated with the Zika virus outbreak across the Americas. Indeed, in 2015, in a review of infections that have neurological consequences, Zika virus was not even mentioned.3 In only 5 months since the detection of the first excess cases of microcephaly in Brazil,4 WHO has declared the clusters of microcephaly and other neurological disorders to be a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.

Contest for AMA leadership positions

AMA Vice President Dr Stephen Parnis and AMA WA President Dr Michael Gannon are competing to lead the AMA for the next two years.

At the close of nominations on 11 May Dr Parnis, a Consultant Emergency Physician at Melbourne’s St Vincent’s Hospital, and Dr Gannon, who is Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Perth’s St John of God Hospital, flagged their intention to contest for the position of AMA President, which will be decided at a ballot at the AMA National Conference on Sunday, 29 May.

The Vice President’s position will also go to a vote after Sydney GP and outgoing Chair of the AMA Council of General Practice, Dr Brian Morton, and immediate-past AMA Victoria President, and Chair-elect of the AMA Council of General Practice, Dr Tony Bartone, both nominated for the post.

Both AMA President and AMA Vice President serve a term of two years.

The AMA National Conference will be held in Canberra on 27 to 29 May.

[Clinical Picture] Hypertrichosis lanuginosa acquisita: a rare dermatological disorder

A 75-year-old woman was brought to the emergency department following a syncopal episode in August, 2007. She had a 6 week history of weight loss, exertional dyspnoea, and non-productive cough, and a 2 month history of increased hair growth. On examination she had new lanugo hair and eyelash trichomegaly (figure), and a deeply furrowed tongue. Work-up showed a mass in the right upper lobe. Histology of a biopsy sample of the mass was consistent with adenocarcinoma of the lung stage 3B. She was given a course of palliative radiotherapy, with minor regression of lanugo hair and some improvement in her dyspnoea and cough.

[Articles] Delivering safe and effective analgesia for management of renal colic in the emergency department: a double-blind, multigroup, randomised controlled trial

Intramuscular non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs offer the most effective sustained analgesia for renal colic in the emergency department and seem to have fewer side-effects.

Ebola crisis: the world must do better

The reputation of the global system for preventing and responding to infectious disease outbreaks has taken a battering in the wake of the west African Ebola epidemic.

Yet a prestigious Independent Panel believes it is possible to rebuild confidence and prevent future disasters, releasing a roadmap of 10 interrelated recommendations for national governments, the World Health Organisation, non-government organisations and researchers.

The Independent Panel on the Global Response to Ebola, launched jointly by the Harvard Global Health Institute and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, spent months reviewing the worldwide response to the outbreak that began in 2013.

“The west African Ebola epidemic … was a human tragedy that exposed a global community altogether unprepared to help some of the world’s poorest countries control a lethal outbreak of infectious disease,” the Panel wrote in The Lancet.

“The outbreak continues … It has infected more than 28,000 people and claimed more than 11,000 lives, brought national health systems to a halt, rolled back hard-won social and economic gains in a region recovering from civil wars, sparked worldwide panic, and cost several billion dollars in short-term control efforts and economic losses.”

See also: AMA pressure on government to act

The Panel said its goal was to convince high-level political leaders worldwide to make necessary and enduring changes to better prepare for future outbreaks while memories of the human costs of inaction remained vivid and fresh.

It identified four key phases of inaction:

- December 2013 to March 2014, when Guinea’s lack of capacity to detect the virus allowed it to spread to neighbouring Liberia and Sierra Leone;

- April to July 2014, when intergovernmental and non-government organisations started to respond, health workers struggled to diagnose patients and provide effective care, national authorities played down the scope of the outbreak, and WHO and the US CDC sent expert teams but withdrew them prematurely;

- August to October 2014, when global attention and responses grew, but so did panic and misinformation, leading to unnecessary and harmful trade and travel bans; and

- October 2014 to September 2015, when cases began to decline, and large-scale global assistance started to arrive, albeit with weak coordination and a lack of accountability for the use of funds.

“This Panel’s overarching conclusion is that the long-delayed and problematic international response to the outbreak resulted in needless suffering and death, social and economic havoc, and a loss of confidence in national and global institutions,” the Panel said.

“Failures of leadership, solidarity and systems came to light in each of the four phases. Recognition of many of these has since spurred proposals for change. We focus on the areas that the Panel identified as needing priority attention and action.”

The Panel made 10 recommendations:

- develop a global strategy to invest in, monitor, and sustain national core capacities;

- strengthen incentives for early reporting of outbreaks and science-based justifications for trade and travel restrictions;

- create a unified WHO Centre for Emergency Preparedness and Response with clear responsibility, adequate capacity, and strong lines of accountability;

- broaden responsibility for emergency declarations to a transparent, politically protected Standing Emergency Committee;

- institutionalise accountability by creating an independent Accountability Commission for Disease Outbreak Prevention and Response;

- develop a framework of rules to enable, govern and ensure access to the benefits of research;

- establish a global facility to finance, accelerate, and prioritise research and development;

- sustain high-level political attention through a Global Health Committee of the Security Council;

- a new deal for a more focused, appropriately financed WHO; and

- good governance of WHO through decisive, time-bound reform, and assertive leadership.

“The human catastrophe of the Ebola epidemic that began in 2013 shocked the world’s conscience and created an unprecedented crisis,” the Panel concluded.

“The reputation of WHO has suffered a particularly fierce blow. Ebola brought to the forefront a central question: is major reform of international institutions feasible to restore confidence and prevent future catastrophes? Or should leaders conclude the system is beyond repair and take ad hoc measures when the next major outbreak strikes?

“After difficult and lengthy deliberation, our Panel concluded major reforms are warranted and feasible.”

Maria Hawthorne

INTEGRATING CARE FOR PATIENTS WITH SERIOUS AND CONTINUING ILLNESS

Rising numbers of patients with serious and continuing illness are set to change the way we provide medical care. They need care that like their ailments, is both serious and continuing.

This is not a new insight. We have known about the increasing load of chronic illness for decades. We know its pattern has changed. We know that while it mainly afflicts older people; children and adolescents who would have died decades ago live on now. They, too, need continuing care. Middle-aged people with cancer or heart disease or mental illness saved from death from an acute illness now likewise need continuing care.

This changing pattern of illness means that hospital and out-of-hospital care must, be better joined up because neither form of care is at its best when managing independent episodes in a long-running story. It means that the way we provide care in future should be built around what is best for the patient, namely, continuous and linked. We have known all this, too – but now the pressure to do better is coming from the community itself.

When the community becomes concerned, politicians respond. The prime minister, Malcolm Turnbull, has committed $38 million this year to trying out ways of linking care for patients with chronic problems, placing the general practitioner in the driving seat.

Meet George Henderson – lets give him that name. I saw him at home several years ago when I was working at the Respiratory Ambulatory Care Service (RACS) at Blacktown Hospital. Two of the nurses who do most of the work of the clinic took me to see him. They had a panel of over 100 patients who had been through the their six week program and were living at home.

George lived in a community-services house. His principal carer was his former wife who had come back for this purpose as their children threatened not to speak to her again unless she did!

We arrived at 10am. He came slowly to the door in pyjamas, trailing a long cord to an oxygen concentrator in his kitchen. He was exhausted when we got him to bed. It was a tiny, lonely room. There was a bedside torch, copious bottles of tablets and on the shelves several small and intricate balsa boat models that he made as his hobby.

The nurses chatted, examined his chest, measured his blood pressure and oxygen saturation. How did he bathe? I asked. He had to clamber over the edge of a bath. There were no handrails. Could we get them installed? One nurse told me this would require authorisation from the hospital social worker. When can she come? I asked. ‘Oh!,’ the nurse laughed. ‘To this suburb? Four weeks! To [an up market neighbouring suburb] one week!’ If he slipped and survived with a broken femur who would be to blame? We would all pay.

I noticed when I assessed him that his teeth were poor. A dental appointment at a hospital outpatient department would take many months. One nurse told me that when they found an acute and serious dental problem, they would send the patient to hospital ‘with an exacerbation’. That way, the nurse said, his dental problem would be speedily sorted. But getting him to hospital ran the risk of oxygen overdose on the way and ICU on arrival for hypercapnia.

To expect a general practitioner to be the centrepiece of George’s care would require remuneration that matched the cost. The doctor would need allied health professional staff immediately at his or her call – physios, nurses and more. Connection to a specialist would have to be immediately available. To give George a sense of confidence he would need to be able to talk to someone who knew and understood him 24/7.

One of the nurses who was on the RACS 24/7 roster told me how George had called at 2am one day, acutely breathless and anxious. She was able to ‘talk him down’, encourage him to breathe as he had been taught, make a cup of tea. She avoided a hugely disruptive emergency visit to hospital.

There is more to integrating care for patients with serious and continuing illness than can be written in bureaucratic documents and business charts. It is a matter, most fundamentally, of our response to the real, grounded problems of the people we care for, the way we respond to growing human needs. Money matters, but it can be found. As a profession we should consider joining our voices to those of our patients in seeking better ways of caring for those with chronic problems.

The National Emergency Access Target (NEAT) and the 4-hour rule: time to review the target

The National Emergency Access Target (NEAT) stipulates that a pre-determined proportion of patients should be admitted, discharged or transferred from Australian emergency departments (EDs) within 4 hours of presentation. Targets that varied from state to state were set for all Australian EDs by the National Partnership Agreement in 20121 in response to evidence that ED overcrowding and prolonged length of stay were associated with increased in-hospital mortality.2,3 The original aim was to incrementally increase the target to 90% in all jurisdictions by 2015, in line with the “4-hour rule” target set in the United Kingdom in 2010.

Despite the potentially major impact of the NEAT upon patient care, there was no prospective standardised framework for monitoring outcomes for patients admitted to hospital from EDs. Measuring patient outcomes is difficult, and no approach is beyond criticism. The hospital standardised mortality ratio (HSMR) is an objective screening tool designed to alert clinicians to potentially avoidable harm, and it has been accepted as a core indicator of hospital safety.4 The HSMR compares the numbers of observed and expected deaths; unlike raw mortality statistics, it excludes the deaths of palliative care patients, and attempts to adjust for clinically relevant risk factors, such as age, sex and principal diagnosis. The HSMR has been clinically useful in Australia, where it has helped guide the clinical re-design of ED admission processes,5,6 and in the UK, where elevated HSMRs helped identify potentially avoidable adverse clinical events in Mid Staffordshire Trust hospitals.7

Retrospective studies in large hospitals in Brisbane,5 Melbourne8 and Perth9 have shown that clinical restructuring induced by the NEAT has been associated with reduced ED crowding, improved patient flows through the ED, and reduced in-hospital mortality. In one study, a rise in NEAT compliance rates from 30% to 70% was strongly correlated with a reduction in HSMR for patients specifically admitted from the ED (eHSMR), from 110 to 67 (R = 0.914, P < 0.001).6

However, certain factors may have confounded these findings. Following the introduction of the NEAT, more low acuity patients, who are less likely to die, may have been admitted to short-stay wards instead of being discharged from the ED more than 4 hours after presenting. This would introduce a bias if risk adjustment were to overestimate the mortality risk of these low risk patients. In addition, increased coding of patients as receiving palliative care after acute admission would increase the number of expected deaths, while the number of observed deaths would remain unchanged, again reducing the eHSMR.10

Putting these interpretive considerations to one side, no hospital in Australia, apart from small rural institutions, has consistently reached 4-hour targets greater than 85%.11 Moreover, despite evidence associating ED overcrowding with increased in-hospital mortality, and reduced mortality in some jurisdictions after introducing a time-based target, uncertainty persists as to whether such targets consistently improve patient outcomes in most hospitals.

Overzealous pursuit of stringent time-based targets may actually compromise quality of care and endanger patient safety. This was seen in the Mid Staffordshire experience in the UK, where elevated HSMRs suggested that avoidable patient harm may have increased after introducing time-based treatment targets.7 A focus on the NEAT must be coupled with patient-centred outcome measures that balance the dual needs for hospital efficiency and safe, effective care.2,3,6,8,9,12,13 The ideal NEAT compliance rate maximises the benefits of decongesting EDs while minimising the potential harms of rushed and suboptimal management of acutely ill patients, and has not yet been determined on the basis of empirical data. A recent literature review of 4-hour targets in Australia and the UK noted that all were arbitrary and lacked validation.14 Another review concluded that the introduction of the 4-hour rule in the UK, undertaken at considerable financial cost, had not resulted in consistent improvements in care, with markedly varying effects between hospitals reported.15 In Australia, the need to determine the optimal NEAT has increased because of the opportunity costs involved in achieving high compliance rates and the loss of financial incentives following dissolution of the National Partnership Agreement in 2014.16,17

The aims of our study were to explore the relationship between eHSMR and NEAT compliance rates using a large dataset from several Australian hospitals, and to assess the effects on this relationship of potential confounding by the inclusion of palliative care and short-stay patients.

Methods

Study design, participating sites and data sources

This retrospective observational study covered the 4-year period from 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2014, spanning the introduction and subsequent focus on the NEAT by Australian governments after signing the National Partnership Agreement on Improving Public Hospital Services in February 2011.1

De-identified data on hospital admissions during the study period were obtained from The Health Roundtable (HRT) in accordance with its academic research policy. The final dataset comprised data from 59 Australian hospitals; all 33 New Zealand hospitals, which were working towards a 6-hour target, were excluded, as were 26 sites in Australia with no general EDs, two specialist hospitals with an atypical mortality profile, and 48 hospitals for which the ED data for the study period were incomplete. With approval from the HRT, the de-identified dataset was independently analysed by investigators from the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) e-Health Research Centre.

Episodes of care and patient cohorts

All patients who presented to an ED of one of the study hospitals and were either admitted to or discharged from the hospital were included in the analysis. For admitted patients, the unit of analysis was the entire hospital stay, preserving any changes in care type during the admission. Elective patients, patients coded as dead on arrival and who had a principal diagnosis of sudden unexplained death or had died in the ED, organ donation episodes, non-acute and geriatric evaluation and management episodes, and all episodes involving neonates were excluded. Patients coded as palliative and short-stay patients (defined as being an inpatient for less than 24 hours) were also excluded from the primary analysis.

In addition, three additional patient cohorts were analysed:

-

patients coded as palliative care patients at the time of death;

-

patients with short stays (defined as a length of hospital stay of less than 24 hours), this cohort serving as a proxy group for patients admitted to short-stay observation wards or clinical decision units, and thereby compensating for inconsistencies between hospitals in coding transfers to these wards as inpatient admissions; and

-

these two cohorts combined.

NEAT compliance rates

The NEAT compliance rate was defined as the proportion of patients with an ED length of stay of less than 4 hours. The rate was calculated separately for all patients (total NEAT) and for patients admitted to inpatient units and designated short-stay units (admitted NEAT).

Main outcome measure

The main outcome measure was the relationship between NEAT compliance rates and inpatient mortality for emergency admissions, as expressed by the eHSMR. The eHSMR was preferred to raw mortality rates for two reasons:

-

The HSMR is the risk-adjusted ratio of the observed to the expected numbers of deaths, which helps account for variations in the acuity of presentations and in hospital activity.

-

The HSMR has been validated in other clinical studies for monitoring patient outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Regression models of eHSMR

Several models were used to calculate the expected number of deaths for the denominator of the eHSMR. In keeping with standard practice,18,19 the data on all included patients were separated into two parts: episodes coded with the top 68 diagnostic codes, which account for 80% of in-hospital deaths (part 1), and episodes accounting for the remaining 20%, whereby the number of individual International Classification of Diseases, revision 10 (ICD-10) codes was reduced from about 1000 to ten broad categories based on the raw proportions of deaths associated with each code (part 2). Model selection for each part consisted of an elastic net model with tenfold cross-validation, with the chosen penalty parameter being the largest λ within one standard deviation of the minimum.20 All models initially included two-way variable interactions. Additional information about the modelling process is available in Appendix 1. Area under the curve measures assessed the predictive ability of the model, with values of 0.85 found for the part 1 model and 0.89 for part 2. Similar values were found for models of the three additional cohorts described above.

Relation between NEAT compliance rates and eHSMR

Emergency presentation data, and observed and expected in-hospital mortality rates were aggregated at monthly levels for each hospital and for each hospital peer group over the study period. Overall NEAT and admitted NEAT compliance rates and eHSMR were then calculated. Exploratory data analysis with linear regression models suggested a complex relationship between NEAT and eHSMR, and non-linear relationships were assessed using a restricted cubic spline with knots at 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 85%, 90% and 95% NEAT compliance rates.

The primary analysis of the NEAT–eHSMR relationship excluded palliative care and short-stay patients; the effects on this relationship of including these patient cohorts were explored in sensitivity analyses of the total cohort and each hospital peer group. Statistical analyses were undertaken in R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing); P < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant.

Ethics approval

An ethics approval exemption was provided by the Metro South Health Human Research Ethics Committee (reference, HREC/15/QPAH/233).

Results

Participating sites

Emergency presentation and admissions data and operating characteristics of the participating hospitals are summarised in Appendix 2, Table 1. ED and inpatient data were aggregated for 12.5 million ED episodes of care and 11.6 million inpatient episodes of care.

NEAT compliance rates

Over the 4-year study period, there was a progressive increase in mean monthly NEAT compliance rates for admitted (25% to 45%), total (56% to 70%) and non-admitted patients (70% to 80%) (Appendix 2, Figure 1).

Relationship between eHSMR and NEAT compliance rates

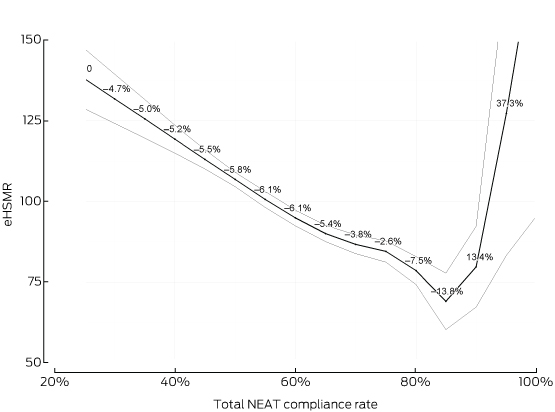

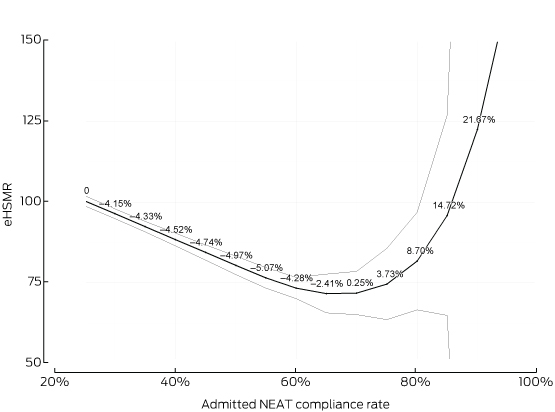

The primary analysis of monthly plots of eHSMR v total NEAT compliance rate (Box 1) and of eHSMR v admitted NEAT compliance rate (Box 2) for all hospitals combined showed similar and significant (P < 0.001) inverse linear relationships until an inflection point was reached. Wide confidence intervals beyond these points reflect the fact that limited data were available.

The eHSMR declined by an average of 5.5% for each five percentage point change in total NEAT compliance rate, reaching a nadir of 73 at a compliance rate of about 83% (range [distance between the two knots in the spline analysis], 80–85%). For admitted NEAT compliance, which included short-stay ward admissions, the eHSMR declined by an average of 4.5% for each five percentage point change in the compliance rate, reaching a nadir of 73 at a compliance rate of about 65% (range, 60–70%).

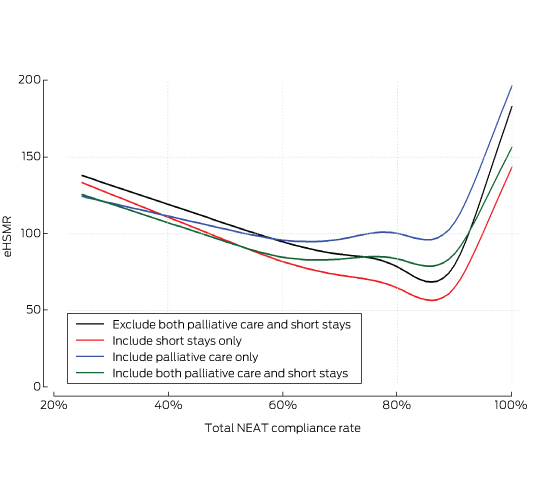

Sensitivity analyses

When the primary analysis was repeated but including either palliative care or short-stay patients, or both, the previously noted relationships between eHSMR and total NEAT compliance were largely unchanged (Box 3).

Discussion

Overview of findings

With the recent abolition of the NEAT, the future of time-based targets for emergency care is unclear. Ours is the first multisite study to assess the relationship between NEAT compliance rates and risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality. An inverse linear relationship was seen as NEAT compliance rates increased to approximately 83% for total NEAT compliance and to 65% for admitted NEAT compliance. Differences between hospitals in the coding of palliative care patients or in the numbers of short-stay patients did not affect the eHSMR–NEAT compliance rate relationships.

Strengths and limitations of the study

Our study has several strengths. First, the analysis involved a very large number of episodes of care over 4 years from a large, representative sample of Australian hospitals, including the 79% of all tertiary hospitals that account for more than 85% of all ED admissions. Second, we were able to use an objective measure of mortality for emergency admissions to hospital and to assess patient outcomes over the period in which the NEAT was introduced. This study helps inform the debate about whether time-based targets should be retained, and, if so, what they should be.

Limitations of the study include the fact that this was an observational study. We identified a reduction in eHSMR as NEAT compliance rates increased to certain values, but this does not prove causality. However, the relationship was highly significant, even in sensitivity analyses that accounted for potential confounders, and we are unaware of any other national hospital quality and safety initiative implemented during the study period. Our omission of some hospitals limits the generalisability of our findings to all institutions. As the primary outcome measure, the eHSMR does not encompass other outcomes important to patients, such as morbidity or quality of life. Further, the use of HSMRs as the basis for cross-sectional, inter-hospital comparisons is controversial.21 Our final models cannot account for errors associated with estimating HSMRs; the denominator is estimated by modelling, and will therefore be imprecise.19 However, the HSMR is objective, accepted as a national measure,4 and serves as a useful indicator of potentially avoidable mortality within individual hospitals when tracked over time, provided there are no major changes in coding practices or admission policies; this applied to our study.21 Finally, the 95% confidence intervals around the mean eHSMR values corresponding to higher NEAT compliance rates broadened as the number of hospitals achieving such rates decreased, so that it is possible that mortality may further decline at higher NEAT compliance rates.

Implications for clinical practice and policy

We found that there is no robust evidence regarding a clinically significant mortality benefit associated with total and admitted NEAT compliance rates above 83% and 65% respectively. Further, as the identified reduction in mortality for admitted patients was associated with increasing total and admitted NEAT compliance rates, it can be argued that both compliance rates should be monitored. Finally, consideration should be given to embedding time-based NEAT compliance rates within a suite of patient-focused outcome measures that can quickly signal any unintended adverse consequences of pursuing ever higher NEAT compliance rates.

Box 1 –

Total National Emergency Access Targets (NEAT) compliance and hospital standardised mortality ratio for patients admitted from emergency departments (eHSMR) for 59 Australian hospitals, 1 July 2010 – 30 June 2014

P < 0.001 for regression (F-test). Pale lines, 95% confidence intervals; graph labels, change in eHSMR per five percentage point change in NEAT.

Box 2 –

Admitted National Emergency Access Targets (NEAT) compliance and hospital standardised mortality ratio for patients admitted from emergency departments (eHSMR) for 59 Australian hospitals, 1 July 2010 – 30 June 2014

P < 0.001 for regression (F-test). Pale lines, 95% confidence intervals; graph labels, change in eHSMR per five percentage point change in NEAT.

Box 3 –

Effects of potential confounders (palliative care and short-stay patients) on relationship between total National Emergency Access Targets (NEAT) compliance and hospital standardised mortality ratio for patients admitted from emergency departments (eHSMR) for 59 Australian hospitals, 1 July 2010 – 30 June 2014

more_vert

more_vert