The emergence of Zika virus (ZIKV) in Brazil coincided with increased reports of newborn babies with microcephaly, congenital malformations, and neurological syndromes.1 In February, 2016, WHO declared ZIKV and microcephaly a Public Health Emergency of International Concern because of the rapid spread of ZIKV infection.2

Preference: Emergency Medicine

202

AMA Awards

President’s Award

Dr Paul Bauert OAM and Dr Graeme Killer AO

Two doctors, one a passionate advocate for the disadvantaged and the other a pioneering force in the care of military veterans, have been recognised with the prestigious AMA President’s Award for their outstanding contributions to the care of their fellow Australians.

Dr Paul Bauert, the Director of Paediatrics at Royal Darwin Hospital, has fought for better care for Indigenous Australians for more than 30 years. More recently, he has taken up the battle for children in immigration detention.

Dr Bauert arrived in Darwin in 1977 as an intern, intending to stay for a year or two. In his words: “I’m still here, still passionate about children’s health and what makes good health and good healthcare possible for all children and their families. I believe I may well have the best job on the planet.”

Dr Graeme Killer, a Vietnam veteran, spent 23 years in the RAAF before becoming principal medial adviser to the Department of Veterans’ Affairs. Over the next 25 years, he pioneered major improvements in the care of veterans, including the Coordinated Veterans’ Care project.

Dr Killer has overseen a series of ground-breaking research studies into the health of veterans, including Gulf War veterans, atomic blast veterans, submariners, and the F-111 Deseal and Reseal program. He was also instrumental in turning around the veterans’ health care system from earlier prejudicial attitudes towards psychological suffering.

Dr Bauert and Dr Killer were presented with their awards by outgoing AMA President, Professor Brian Owler, at the AMA National Conference Gala Dinner.

Excellence in Healthcare Award

The Excellence in Healthcare Award this year recognised a 20-year partnership devoted to advancing Aboriginal health in the Northern Territory.

Associate Professor John Boffa and Central Australian Aboriginal Congress CEO Donna Ah Chee were presented with the Award for their contribution to reducing harms of alcohol and improving early childhood outcomes for Aboriginal children.

Associate Professor Boffa has worked in Aboriginal primary care services for more than 25 years, and moved to the Northern Territory after graduating in medicine from Monash University.

As a GP and the Chief Medical Officer of Public Health at the Central Australian Aboriginal Congress, he has devoted his career to changing alcohol use patterns in Indigenous communities, with campaigns such as ‘Beat the Grog’ and ‘Thirsty Thursday’.

Ms Ah Chee grew up on the far north coast of New South Wales and moved to Alice Springs in 1987. With a firm belief that education is the key pathway to wellbeing and health, she is committed to eradicating the educational disadvantage afflicting Indigenous people.

Between them, the pair have initiated major and highly significant reforms in not only addressing alcohol and other drugs, but in collaborating and overcoming many cross-cultural sensitivities in working in Aboriginal health care.

Their service model on alcohol and drug treatment resulted in a major alcohol treatment service being funded within an Aboriginal community controlled health service.

AMA Woman in Medicine Award

An emergency physician whose pioneering work has led to significant reductions in staph infections in patients is the AMA Woman in Medicine Award recipient for 2016.

Associate Professor Diana Egerton-Warburton has made a major contribution to emergency medicine and public health through her work as Director of Emergency Research and Innovation at Monash Medical Centre Emergency Department, and as Adjunct Senior Lecturer at Monash University.

Her just say no to the just-in-case cannula has yielded real change in practice and has cut staff infections in patients, while her Enough is Enough: Emergency Department Clinicians Action on Reducing Alcohol Harm project developed a phone app that allows clinicians to identify hazardous drinkers and offer them a brief intervention and referral if required.

Associate Professor Egerton-Warburton has been passionate about tackling alcohol harm, from violence against medical staff in hospitals to domestic violence and street brawls.

She championed the first bi-annual meeting on public health and emergency medicine in Australia and established the Australasian College of Emergency Medicine’s alcohol harm in emergency departments program.

In addition, she has developed countless resources for emergency departments to facilitate management of pandemic influenza and heatwave health, and has authored more than 30 peer-reviewed publications.

Professor Owler said Associate Professor Egerton-Warburton’s tireless work striving for high standards in emergency departments for patients and her unrelenting passion to improve public health made her a deserving winner of the Award.

AMA Doctor in Training of the Year Award

Trainee neurosurgeon Dr Ruth Mitchell has been named the inaugural AMA Doctor in Training of the Year in recognition of her passion for tackling bullying and sexual harassment in the medical profession.

Dr Mitchell, who was a panellist in the Bullying and Harassment policy session at National Conference, is in her second year of her PhD at the University of Melbourne, and is a neurosurgery registrar at the Royal Melbourne Hospital.

Presenting the award, Professor Owler said Dr Mitchell had played a pivotal role in reducing workplace bullying and harassment in the medical profession and was a tireless advocate for doctors’ wellbeing and high quality care.

MJA/MDA National Prize for Excellence in Medical Research

A study examining the impact of a widely-criticised ABC TV documentary on statin use won the award for best research article published in the Medical Journal of Australia in 2015.

Researchers from the University of Sydney, University of NSW and Australian National University found that tens of thousands of Australians stopped or reduced their use of cholesterol-lowering drugs following the documentary’s airing, with potentially fatal consequences.

In 2013, the science program Catalyst aired a two-part series that described statins as “toxic” and suggested the link between cholesterol and heart disease was a myth.

The researchers found that in the eight months after program was broadcast, there were 504,180 fewer dispensings of statins, affecting more than 60,000 people and potentially leading to as many as 2900 preventable heart attacks and strokes.

AMA/ACOSH National Tobacco Scoreboard Award and Dirty Ashtray

The Commonwealth Government won the AMA/ACOSH National Tobacco Scoreboard Award for doing the most to combat smoking and tobacco use, while the Northern Territory Government won the Dirty Ashtray Award for doing the least.

The Commonwealth was commended for its continuing commitment to tobacco control, including plain packaging and excise increases, but still only received a B grade for its efforts.

The Northern Territory received an E grade for lagging behind all other jurisdictions in banning smoking from pubs, clubs, and dining areas, and for a lack of action on education programs.

State Media Awards

Best Lobby Campaign

AMA NSW won the Best Lobby Campaign award for its long-running campaign to improve clinician engagement in public hospitals.

The campaign started after the Garling Inquiry in 2008, which identified the breakdown of trust between public hospital doctors and their managers as an impediment to good, safe patient care.

It led to a world-first agreement between the NSW Government and doctors, signed in February 2015 by Health Minister Jillian Skinner, AMA NSW and the Australian Salaried Medical Officers’ Federation NSW, to embed clinician engagement in the culture of the public hospital system, and to formally measure how well doctors are engaged in the decision-making processes.

Best Public Health Campaign

AMA NSW also took home the Best Public Health Campaign award for its innovative education campaign on sunscreen use and storage.

The campaign drew on new research which found that many Australians do not realise that sunscreen can lose up to 40 per cent of its effectiveness if exposed to temperatures above 25 degrees Celsius.

The campaign received an unexpected boost with the release of survey results showing that one in three medical students admitted to sunbaking to tan, despite knowing the cancer risk.

Best State Publication

AMA WA won the highly competitive Best State Publication award for its revamped Medicus members’ magazine.

The 80-page publication provides a mix of special features, clinical commentaries, cover articles and opinion pieces to reflect the concerns and interests of WA’s medical community and beyond.

The judges said that with its eye-catching covers, Medicus made an immediate impact on readers.

Most Innovative Use of Website or New Media

AMA WA won the award for its Buildit portal, a mechanism for matching trainee doctors with research projects and supervisors.

The judges described Buildit as taking the DNA of a dating app and applying it to the functional research requirements of doctors in training, allowing for opportunities that may have otherwise been missed.

National Advocacy Award

AMA Victoria won the National Advocacy Award for its courage and tenacity in tackling bullying, discrimination and harassment within the medical profession.

AMA Victoria sought the views and concerns of its members, and made submissions to both the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons’ inquiry and the Victorian Auditor-General’s audit of bullying, harassment and discrimination within state public hospitals.

The judges said that tackling a challenge within your own profession was a particularly difficult task, especially in the glare of public scrutiny, making the AMA Victoria campaign a standout.

Maria Hawthorne

“If in doubt, sit them out” – new guidelines for concussion in sport

Children and teenagers with suspected sport-related concussion should be kept from training or playing for at least two weeks after their symptoms clear, new guidelines developed jointly by the AMA and the Australian Institute of Sport recommend.

The nation’s leading medical and sporting bodies teamed up to develop new guidelines and resources for dealing with concussion on the sporting field.

“Concussion is something that occurs on the sporting fields. It’s not just something that occurs for professional athletes,” outgoing AMA President, Professor Brian Owler, said at the launch of the new website, concussioninsport.gov.au.

“This resource is designed for those coaches, trainers, teachers, parents – those people who are dealing with injuries that happen on sporting fields on Saturday mornings, or on school days.

“I hope that parents and coaches can use this resource. It gives them some reassurance, and we can get some better management of concussion and make sure that we avoid some of the problems that can come along if people don’t pay enough attention to it.”

AIS figures show a 60 per cent rise in the number of people admitted to hospital for sport-related concussion over the past decade, it is estimated there are as many as 100,000 sports-related concussions each year.

But general knowledge about concussion management at a community sporting level in Australia is poor.

“I’ve been in sports medicine for 25 years, and I have to say that I still find each case of concussion challenging,” AIS Chief Medical Officer, Dr David Hughes, said. “I certainly know from my discussions with athletes, parents, and coaches that concussion is an issue that causes a certain amount of anxiety and concern, and rightly so.”

The concussioninsport.gov.au website provides simple but specific advisory tools for athletes, parents, teachers, coaches and medical practitioners.

“There are videos that are recorded by experts from the sporting world, and also GPs, emergency doctors and myself as a neurosurgeon,” Professor Owler said.

“It shows the important things that people need to look out for, and also gives some pretty clear instructions on how to manage concussion in terms of return to training and returning to play.”

The website, and the joint AMA-AIS Position Statement on Concussion in Sport, recommends that children avoid full-contact training or sporting activity until at least 14 days after all symptoms of concussion have cleared.

“We’ve erred on the side of caution,” Professor Owler said.

“No-one is going to have ill-effects from sitting out two weeks of sport. But we know that if people go back too early, then they risk having more concussion, and it’s the compounding effects of concussion that can actually end their playing careers.”

Dr Hughes said there was growing evidence that children were more susceptible to, and took longer to recover from, concussion.

“It’s not the most conservative policy in the world,” Dr Hughes said. A group in Scotland has recommended a four week break, but he said the evidence did not support such a long period.

He said the policy was closely aligned with World Rugby’s current policy on children in sport, and “we certainly feel strongly that children should not be treated the same way as adults when it comes to concussion in sport.”

The joint AMA-AIS Position Statement on Concussion in Sport and a new website, concussioninsport.gov.au, were released at the 2016 AMA National Conference in Canberra.

The Position Statement can be viewed at: position-statement/concussion-sport-2016

Maria Hawthorne

AMA calls for fair go for bush health

The AMA has encouraged all major political parties to deliver significant real funding increases for health care in regional, rural and remote Australia.

Immediate-past President Professor Brian Owler made the appeal when he launched the AMA’s plan for Better Health Care for Regional, Rural, and Remote Australia at Parliament House last month.

Professor Owler said that the life expectancy for those living in regional areas was up to two years less than the broader population, and up to seven years less in remote areas, and needed to change.

“It is essential that Government policy and resources are tailored and targeted to cater to the unique nature of rural health care and the diverse needs of rural and remote communities to ensure they receive timely, comprehensive, and quality care,” Professor Owler said.

The AMA plan focusses on four key measures – rebuilding country hospital infrastructure; supporting recruitment and retention; encouraging more young doctors to work in rural areas; and supporting rural practices.

The plan encourages Federal, State and Territory governments to work together to ensure that rural hospitals are adequately funded to meet the needs of their local communities. More than 50 per cent of small rural maternity units have closed in the past two decades.

Professor Owler said rural hospitals needed modern facilities, and must attract a sustainable health workforce.

“We need to invest in hospital infrastructure,” Professor Owler said. “When hospitals don’t have investment, when their infrastructure runs down, it makes it much harder for rural doctors to service patients in their communities.”

He called on the Council of Australian Government (COAG) to consider a detailed funding stream for rural hospitals, backed by a national benchmark and performance framework.

Professor Owler visited a rural GP practice at Bungendore and spoke with the local doctors about the issues and barriers of delivering high quality timely health care to the community.

“General practice is the backbone of rural health care, providing high quality primary care services for patients, procedural and emergency services at local hospitals, as well as training the next generation of GPs,” Professor Owler said.

“Rural GPs would like to do more, but face significant infrastructure limitations in areas such as IT, equipment, and physical space.

“Rural general practices need to be properly funded to improve their available infrastructure, expand services they provide to patients and support improved opportunities for teaching in general practice.”

The AMA has recommend that the Government fund a further 425 rural GP infrastructure grants, worth up to $500,000 each, to assist rural GPs.

Professor Owler added that timely access to a doctor was a key problem for people living in rural areas, with the overall distribution of doctors skewed heavily towards the major cities. He said the burden of medical workforce shortages fell disproportionately on communities in regional, rural and remote areas.

The number of GP proceduralists or generalists working across rural and remote Australia has steadily been declining. In 2002, 24 per cent of the Australian rural and remote general practice workforce consisted of GP proceduralists. By 2014, this level had dropped to just under 10 per cent.

The AMA and the Rural Doctors Association of Australia have together developed a package that recognises both the isolation of rural and remote practice and the need for the right skill mix in these areas.

The AMA Better Health Care for Regional, Rural, and Remote Australia is available at gp-network-news/ama-plan-better-health-care-regional-…

Kirsty Waterford

News briefs

Wearable sensor measures fitness levels, heart function

Researchers from the University of California-San Diego in the US have developed a wearable patch that can measure biochemical and electrical signals in the human body simultaneously, reports Medical News Today. “The device — called the Chem-Phys patch — measures real-time levels of lactate, an indicator of physical activity, as well as the heart’s electrical activity. Put simply, the novel technology monitors a person’s fitness levels and heart function at the same time, and it is the first device that can do so. The patch is made of a thin, adhesive, flexible sheet of polyester, which the researchers manufactured using screen printing. A lactate-sensing electrode is situated in the centre of the patch, and two electrocardiogram electrodes are situated either side. The researchers found that the data collected by the EKG electrodes closely matched the data collected by a commercial heart rate monitor. Furthermore, they found that the information gathered by the lactate sensor closely matched lactate data collected during increasing physical activity in previous studies.”

http://www.nature.com/ncomms/2016/160523/ncomms11650/full/ncomms11650.html

Obesity linked to lower quality of nursing home care

US researchers have found that nursing homes that admitted more morbidly obese residents were also more likely to have more severe deficiencies in care, according to a study published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. Science Daily reports that the study was designed to find out “whether obese older adults were as likely as non-obese elders to be admitted to nursing homes that provided an appropriate level of care”. “The researchers examined 164 256 records of obese people aged 65 or older who were admitted to nursing homes over a 2-year period. They also examined the nursing homes’ total number of deficiency citations and quality-of-care deficiencies to determine the quality of care that the homes provided. The researchers reported that about 22% of older adults admitted to nursing homes were obese. Nearly 4% were considered morbidly obese. Nursing homes that admitted a higher number of obese residents were more likely to have a higher number of deficiencies.”

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/05/160531182543.htm

Australians among world’s longest-living: WHO

A new report from the World Health Organization says there have been gains in global life expectancy since 2000, with the overall increase of 5 years to a tick over 71 years the fastest rise since the 1960s, and reverses the declines seen in the 1990s. The World health statistics 2016: monitoring health for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) report shows that the greatest increase in life expectancy during 2000–2015 has been in the African region, where it rose from 9.4 years to 60 years, due to reduction in child deaths, progress in malaria control, and better access to HIV antiretrovirals. Globally, the average lifespan of a child born in 2015 is likely to be 71.4 years — or 73.8 years if it is a girl and 69.1 years if it is a boy. The longest life expectancy is in Japan, where children born in 2015 are expected to live 83.7 years, followed by Switzerland (83.4 years), Singapore (83.1 years), Australia (82.8 years), and Spain (82.8 years). Average life expectancy for the United States is 79.3 years. The report also quantifies the causes of death and ill-health that pose significant challenges in meeting the SDGs.

http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/2016/en/

Beware barbecue brush bristles

Research published in Otolaryngology — Head and Neck Surgery has investigated the epidemiology of wire-bristle barbecue brush injuries. Between 2002–2014, more than 1600 emergency department visits occurred as a result of wire-bristle brush injuries in the US, some of them requiring surgery. According to Medical News Today: “While wire grill brushes may be an effective cleaning tool prior to or following a cookout, the bristles can easily fall off and make their way into people’s food. If ingested, these little strands of metal can cause some serious injuries to the mouth, throat, and gastrointestinal region. The researchers hope their findings will promote greater awareness among manufacturers, consumers, and healthcare providers of the potential health hazards associated with wire-bristle brushes.”

Trends in severe traumatic brain injury in Victoria, 2006–2014

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is the most significant cause of death and severe disability resulting from major trauma.1 The economic burden of TBI is significant, with estimated annual hospital costs of $184 million in Australia.2 Although severe TBI constitutes a small proportion of all TBI,3 these injuries are a significant public health problem, associated with high mortality, profound long term disability, and significant long term health care costs.4,5

While there is evidence that mortality associated with severe TBI has not changed since 1990,6 data on temporal trends in the incidence and causes of severe TBI are limited. Understanding the epidemiological patterns of severe TBI is necessary for developing targeted interventions and evaluating injury prevention strategies. This is particularly important given the worldwide focus on the prevention of falls and road trauma, the major causes of severe TBI.5,7,8

The aim of this study was therefore to examine trends in the incidence and causes of hospitalisations for severe TBI across a statewide population (Victoria) over a 9-year period (2006–2014).

Methods

A retrospective review of severe TBI cases was conducted, using data from the Victorian State Trauma Registry (VSTR) for the period 1 January 2006 – 31 December 2014.

Victorian State Trauma Registry

The VSTR is a population-based registry that collects data about all patients hospitalised in Victoria with major trauma.9 A case is included in the VSTR if any of the following criteria are met:

-

the injury results in death;

-

an injury severity score greater than 12 is determined using the Abbreviated Injury Scale (2005 version, 2008 update = AIS 200810);

-

the patient is admitted to an intensive care unit for more than 24 hours and mechanical ventilation is required for at least part of this stay; or

-

the patient undergoes urgent surgery.

Definition of severe TBI

Severe TBI was defined as trauma with an AIS (2005 version, 2008 update) score for the head region of at least 3 and a Glasgow Coma Scale11 (GCS) score of 3 to 8. A head region AIS score of 3 or more indicates an anatomical injury with a rating of serious or higher; a GCS score in the range 3 to 8 is often used as the criterion for severe brain injury.5,7 The combination of anatomical and physiological measures to define severe TBI avoided including patients whose low levels of consciousness were not caused by a head injury, but by alcohol or drug intoxication, for example. Injury diagnoses coded before the introduction of the AIS 2008 were mapped from the AIS 1990, 1998 version to the AIS 2008 using a validated map.12 When possible, the GCS score was recorded on arrival at the hospital to which the patient was initially transported (this occurred for 716 patients, or 35% of all cases analysed in our study). If this was unavailable, the pre-hospital GCS score recorded by paramedics (1080 patients, 52%) was used, or the GCS score recorded on arrival at the definitive hospital (the hospital at the highest service level in the tiered trauma system structure at which the patient was treated: six patients, 0.3%). The GCS score was coded as 3 when pre-hospital, primary hospital and definitive hospital GCS scores were all unavailable because the patient had been intubated (260 patients, 13%). Pre-hospital deaths and events experienced by patients outside Victoria subsequently transported to Victorian hospitals were excluded from analysis.

Procedures

Severe TBI cases were stratified by intent of the event causing the injury (those resulting from unintentional or intentional events), as the strategies for preventing TBI are different for these two categories. Unintentional events were classified as transport-related (involving motor vehicles, motorcycles, pedestrians or cyclists), falls (low falls from standing or no more than one metre, or unintentional high falls from a height of greater than one metre), or other. Intentional severe TBI cases were classified as interpersonal violence or self-harm events. Patient age was categorised into five bands (0–4, 5–14, 15–34, 35–64 and ≥ 65 years). Event locations were mapped to Victorian Government Department of Health regions13 and classified as metropolitan or rural.

Statistical analysis

Population-based incidence rates and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated for each calendar year. Population estimates for Victoria for each year were obtained from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.14 Comparisons of crude and age–sex-standardised incidence rates (standardised according to the five age categories) found substantial concordance (overall severe TBI incidence: Lin concordance correlation coefficient ρ = 0.999 [95% CI, 0.999–1.000; P < 0.001]). Crude incidence rates are therefore reported. Poisson regression was used to determine whether the incidence rate increased or decreased over the 9-year period. A check for potential overdispersion of the data was performed to ensure that the assumptions of a Poisson distribution were met. The incidence rate ratio (IRR) and 95% CIs were calculated, and P < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. Stata 13 (StataCorp) was used for all analyses.

Ethics approval

The VSTR has approval from institutional ethics committees of all 138 hospitals receiving patients who have suffered a trauma (Department of Health Human Research Ethics Committee; reference, 11/14) and the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (MUHREC; reference, CF13/3040-2001000165). This study was approved by the MUHREC (reference, CF12/3965-2012001903).

Results

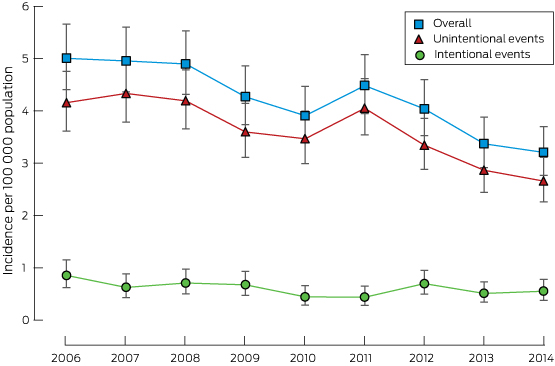

There were 2062 hospitalisations for severe TBI in Victoria during the 9-year study period, comprising 9% of all major trauma cases. Most patients were men, and 40% were aged 15–34 years; most incidents occurred in metropolitan areas (65%) and were the result of unintentional events (86%) (Box 1). The overall incidence of severe TBI was 4.20 cases per 100 000 population per year, with a significant decrease over the study period from 5.00 to 3.20 cases per 100 000 population per year (IRR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.93–0.96; P < 0.001; Box 2). The overall proportion of patients who died in hospital was 42.5%, and was highest in those aged over 64 years (78%; Box 3). Annual incidence rates are provided in the Appendix.

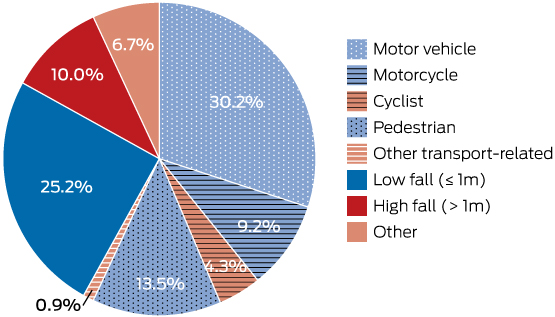

Unintentional events

The overall incidence of severe TBI resulting from unintentional events was 3.60 cases per 100 000 population per year, and the incidence decreased 5% per year during the study period (IRR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.93–0.96; P < 0.001; Box 2). The major causes of injury resulting from unintentional events were transport-related (58.1%) and falls (35.2%) (Box 4). Transport-related severe TBI involving motor vehicle crashes (51.9%) and pedestrians (23.3%) were the most frequent types (Box 3).

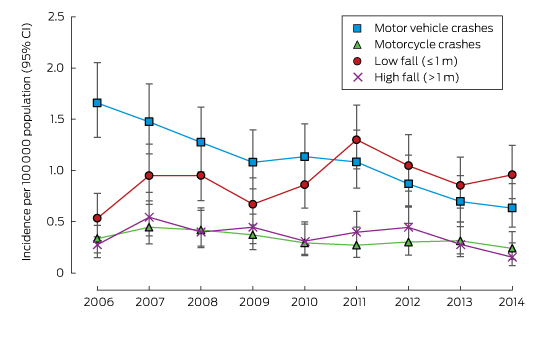

Severe TBI resulting from motor vehicle crashes (Box 5) was most frequent in the 15–34-year-old age group (64.7%; Box 3). The incidence of severe TBI involving motor vehicle occupants declined over the study period (IRR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.86–0.92; P < 0.001), as did those of severe TBI involving cyclists (IRR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.80–0.96; P = 0.003) or pedestrians (IRR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.90–1.00; P = 0.04). The incidence of severe TBI in motorcyclists declined by 6% per year, but this was not statistically significant (IRR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.89–1.00; P = 0.06).

Seventy-two per cent of fall-related severe TBIs were the result of a fall from standing or from no more than one metre. The incidence of severe TBI from low falls increased over the study period (IRR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.00–1.08; P = 0.03), while the incidence of severe TBI caused by high falls decreased (IRR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.89–1.00; P = 0.04). Low falls were most frequent among people aged 65 years or more (68.1%; Box 3).

Intentional events

The overall incidence of severe TBI resulting from intentional events was 0.60 cases per 100 000 population per year (Box 2); this declined across the study period (IRR, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.91–1.00; P = 0.03). Intentional events resulting in severe TBI were classified as interpersonal violence (64.9%) or self-harm events (35.1%). Annual numbers in these subgroups were too small for analysing trends. The most common causes of severe TBI caused by self-harm were high falls (31.7%), transport-related events (26.9%), asphyxiation (19.2%), and firearm use (19.2%). The most common cause of severe TBI resulting from interpersonal violence was being struck by a person or object (84.9%).

Discussion

Our study investigated trends in the incidence and causes of severe TBI leading to hospitalisation over a 9-year period. The incidence of severe TBI resulting from unintentional and intentional events decreased by 5% per year. The reduction in severe TBI resulting from unintentional events was predominantly driven by reductions in transport-related severe TBI. Over the same period, the incidence of low falls-related severe TBI increased, and these injuries were mainly sustained by older adults.

This study is the first to specifically focus on the incidence of severe TBI in Australia across all age groups. The rates reported by the few studies that have examined the incidence of severe TBI have varied (cases per 100 000 population per year: Norway, 4.1;7 Switzerland, 10.6;15 Canada, 11.4;5 France, 17.38). The overall incidence of severe TBI found by our study (4.20 cases per 100 000 population per year) was similar to that in the Norwegian study, which investigated patients hospitalised with severe TBI during 2009–2010, but was lower than in most other studies. This is at least partly explained by differences in the inclusion criteria applied; most studies used head AIS8,15 scores alone to define severe TBI, whereas our study and the Norwegian investigation employed a combination of head injury classification (AIS scores or International Classification of Diseases, revision 10 codes) and GCS score. There may also be genuine differences between countries in the incidence of severe TBI resulting from differing exposures to high risk activities. We found a decline in the incidence of severe TBI over the 9-year period. This contrasts with earlier studies that included all degrees of TBI severity,5,16 which found no significant changes in incidence. However, these studies were conducted over shorter time periods5 or only at two time points,16 potentially explaining the lack of detectable trends.

Falls and transport-related events were the most common causes of severe TBI, and this is consistent with Australian17 and international data.5,7,8,16 It is notable that the incidence of severe TBI resulting from motor vehicle crashes declined over the study period. This reduction is possibly explained by continued improvements in vehicle safety, as well as road safety mass media campaigns. Active safety design measures, such as electronic stability control (ESC) and autonomous emergency braking substantially reduce crash risk;18 ESC has been a mandatory safety feature in new vehicles sold in Victoria since 2011. Similarly, passive safety features, such as curtain airbags, substantially reduce head injuries in side impact crashes.19

Declines in the incidence of severe TBI in pedestrians and cyclists were also noted. These declines may be associated with improvements to road infrastructure, such as pedestrian zones with lower speed limits, and separated bike lanes and paths. Continued efforts to improve infrastructure (including separating pedestrians and cyclists from motor vehicles) and safety (such as increasing helmet use and improving vehicle design to mitigate pedestrian injury) may lead to further declines in the incidence of severe TBI in these vulnerable road users.

There was also a decline in the incidence of severe TBI in motorcyclists, but this was not statistically significant. A review of motorcycle fatalities in Australia indicated that risky riding behaviour (excessive speed, the influence of alcohol and drugs, disobeying traffic control laws) was involved in 70% of events.20 Interventions targeting these behaviours, including mass media campaigns and increased law enforcement, may further reduce severe TBI rates. Consideration should also be given to active safety features in motorcycles, such as antilock braking systems.

Falls were the second most common cause of severe TBI in our study. The incidence of severe TBI from low falls, which occurred mainly in those aged 65 years or more, increased between 2006 and 2014. Increases in this group have also been observed in New South Wales21 and internationally.5 This may be a result of ageing populations, increased rates of comorbidities, and more widespread use of anticoagulant and antiplatelet drugs.16,21 These medications are effective in preventing stroke and thrombo-embolism,22 but increase the complexity of managing trauma patients; further studies examining the incidence of trauma-related complications are needed. The proportion of the Australian population aged 65 years or more is expected to double between 2005 and 2050,23 and our results and international data3 show that TBI outcomes are noticeably worse in older than in younger people. It is therefore clear that further research is required to reduce the incidence of severe TBI in older people. While an overall increase in the incidence of severe TBI resulting from falls was observed across the entire study period, a decline was observed for 2011–2014. This suggests that recent fall prevention programs may have been effective, although further data are needed to explain this trend.

The incidence of severe TBI resulting from intentional events (14.4% of all severe TBI) was similar to that reported by an American study (17.8%).24 We found that this incidence declined during the study period. Interpersonal violence was the primary cause of severe TBI resulting from intentional events, and this has been strongly associated with alcohol intoxication;25 continuing targeted interventions for limiting alcohol consumption through education and by tighter controls at licensed venues may reduce its incidence. Self-harm events accounted for 35.1% of severe TBI resulting from intentional events, but numbers for this group were insufficient for assessing trends. Australian data indicate that suicide rates declined from 1999–2000 to 2010–11, but the incidence of hospitalisation after intentional self-harm remained steady.26 While the number of patients hospitalised with severe TBI resulting from self-harm is small relative to that related to unintentional events, self-harm remains a significant public health problem, and further efforts to improve mental health care and provide early interventions are needed.

The major strength of our study was the use of the population-based VSTR to provide a comprehensive overview of the incidence of severe TBI. However, a number of limitations are acknowledged. Our study was observational, so that identifying causal explanations for the reported trends is beyond its scope; we can only postulate that certain factors may explain these trends. The denominator used to calculate crude incidence was the population of Victoria during the relevant year; we do not have data on the number of people undertaking specific activities (such as cyclists or pedestrians) or the actual time they were at risk of injury. Using the catchment population as the denominator, however, is a widely employed approach.5,7,8,16 Pre-hospital deaths were excluded from this study, so that the true incidence of severe TBI may have been underestimated. Additionally, our analysis was under-powered for assessing combined age- and event-specific trends over time. Further research is needed to understand the mortality and functional outcomes for patients with severe TBI.

Conclusion

Given the devastating consequences of severe TBI, efforts in both primary and secondary prevention are critical to reducing mortality and non-fatal injury burden. In this study of patients hospitalised with major trauma between 2006 and 2014, the incidence of severe TBI resulting from motor vehicle crashes declined, while severe TBI resulting from falls increased over time. Ongoing efforts to reduce road trauma, interpersonal violence and intentional self-harm injury are warranted, while increased efforts to reduce falls-related injuries and injuries to vulnerable road users are needed.

Box 1 –

Profile of patients with severe traumatic brain injury in Victoria, 2006–2014, stratified by unintentional and intentional causal events

|

|

All cases |

Unintentional events |

Intentional events |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Total number |

2062 |

1766 (85.6%) |

296 (14.4%) |

||||||||||||

|

Sex |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Male |

1482 (71.9%) |

1236 (70.0%) |

246 (83.1%) |

||||||||||||

|

Female |

580 (28.1%) |

530 (30.0%) |

50 (16.9%) |

||||||||||||

|

Age |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

0–4 years |

74 (3.6%) |

57 (3.2%) |

17 (5.7%) |

||||||||||||

|

5–14 years |

86 (4.2%) |

84 (4.8%) |

2 (0.7%) |

||||||||||||

|

15–34 years |

827 (40.1%) |

673 (38.1%) |

154 (52.0%) |

||||||||||||

|

35–64 years |

585 (28.4%) |

475 (26.9%) |

110 (37.2%) |

||||||||||||

|

≥ 65 years |

490 (23.8%) |

477 (27.0%) |

13 (4.4%) |

||||||||||||

|

Region |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

Metropolitan |

1338 (64.9%) |

1124 (63.7%) |

214 (72.3%) |

||||||||||||

|

Rural |

724 (35.1%) |

642 (36.4%) |

82 (27.7%) |

||||||||||||

|

Maximum head AIS score |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

AIS 3 |

385 (18.7%) |

328 (18.6%) |

57 (19.3%) |

||||||||||||

|

AIS 4 |

588 (28.5%) |

498 (28.2%) |

90 (30.4%) |

||||||||||||

|

AIS 5 |

1051 (51.0%) |

911 (51.6%) |

140 (47.3%) |

||||||||||||

|

AIS 6 |

7 (0.3%) |

6 (0.3%) |

1 (0.3%) |

||||||||||||

|

AIS 9* |

31 (1.5%) |

23 (1.3%) |

8 (2.7%) |

||||||||||||

|

Outcome |

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

In-hospital mortality |

877 (42.5%) |

757 (42.9%) |

120 (40.5%) |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

AIS=Abbreviated Injury Scale. All percentages are column percentages, except first row (“total number”). *An AIS score of 9 indicates that there was not enough information for more detailed coding. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 3 –

Profile of patients with severe traumatic brain injury in Victoria, 2006–2014, by age group and cause of injury*

|

|

Age group |

All |

|||||||||||||

|

0–4 years |

5–14 years |

15–34 years |

35–64 years |

≥65 years |

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Unintentional events† |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Transport-related |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Motor vehicle crashes |

17 (3.2%) |

22 (4.1%) |

345 (64.7%) |

123 (23.1%) |

26 (4.9%) |

533 (51.9%) |

|||||||||

|

Motorcycle crashes |

0 |

10 (6.2%) |

94 (58.0%) |

55 (34.0%) |

3 (1.9%) |

162 (15.8%) |

|||||||||

|

Cyclist |

0 |

10 (13.0%) |

24 (31.2%) |

34 (44.2%) |

9 (11.7%) |

77 (7.5%) |

|||||||||

|

Pedestrian |

12 (5.0%) |

23 (9.6%) |

84 (35.1%) |

63 (26.4%) |

57 (23.8%) |

239 (23.3%) |

|||||||||

|

Other transport-related |

0 |

2 (13.3%) |

8 (53.3%) |

1 (6.7%) |

4 (26.7%) |

15 (1.5%) |

|||||||||

|

Falls |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Low (≤ 1 m) |

13 (2.9%) |

5 (1.1%) |

29 (6.5%) |

95 (21.3%) |

303 (68.1%) |

445 (71.7%) |

|||||||||

|

High (> 1 m) |

0 (0.0%) |

6 (3.4%) |

50 (28.4%) |

59 (33.5%) |

61 (34.7%) |

176 (28.3%) |

|||||||||

|

Intentional events |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

Interpersonal violence |

17 (8.9%) |

0 |

110 (57.3%) |

60 (31.3%) |

5 (2.6%) |

192 (64.9%) |

|||||||||

|

Self-harm |

0 |

2 (1.9%) |

44 (42.3%) |

50 (48.1%) |

8 (7.7%) |

104 (35.1%) |

|||||||||

|

Outcomes‡ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

|

In-hospital mortality |

24 (32.4%) |

16 (18.6%) |

231 (27.9%) |

225 (38.5%) |

381 (77.8%) |

877 (42.5%) |

|||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

*All percentages are row percentages (ie, contribution of each age group to each cause category), except the final column (“All”), in which the contribution of each subcategory to transport-, fall- or intentional event-related traumatic brain injury is given. †Unintentional events resulting from “other” injury causes (not transport- or fall-related: 119 cases) are not included in this table. ‡For all severe traumatic brain injury. |

|||||||||||||||

[Correspondence] Measurement of cardiac troponin for exclusion of myocardial infarction

In a prospective cohort study using a high-sensitivity cardiac troponin assay, Anoop Shah and colleagues1 determined an optimal threshold of circulating troponin to identify patients suitable for immediate discharge among those presenting to emergency departments with suspected acute coronary syndrome. The threshold of less than 5 ng/L could identify almost two-thirds of patients without myocardial infarction along with a high negative predictive value of 99·6% in the entire cohort. These findings are probably generalisable, because a recent meta-analysis of 23 studies,2 which evaluated troponin concentrations using a different high-sensitivity assay, generated similar results, and found that the threshold of 3–5 ng/L will miss up to 1% of patients with myocardial infarction.

[Correspondence] Network for strong, national, public health institutes in west Africa

The first major epidemic of the Ebola virus disease in West Africa is not yet behind us. The Ebola virus disease epidemic showed that most countries and the international community were not prepared to respond well and in a timely way to this global health emergency.

[Editorial] World Humanitarian Summit: next steps crucial

Ban Ki-moon’s final flagship initiative for his tenure as UN Secretary-General, the World Humanitarian Summit, was held in Istanbul, Turkey, last week (May 23–24). The meeting, the first of its kind, was marred in controversy before it started, with Médecins Sans Frontières boycotting the event because it did not believe that it would address the weaknesses in humanitarian action and emergency response. Other non-governmental organisations (NGOs) were sceptical too. Were they right?

[Comment] REACTing: the French response to infectious disease crises

In the past decade, scientific and health systems have been challenged by an increase in the emergence of infectious diseases such as Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, chikungunya, Ebola virus disease, and Zika virus.1–4 An effective and global public health response to these crises depends on our ability to anticipate these events and our level of preparedness. However, the development of research programmes in response to a rapidly emerging infectious disease in an emergency context is a challenge.

more_vert

more_vert