GPs, inevitably involved in disasters, should be appropriately engaged in preparedness, response and recovery systems

In the past two decades it is estimated that Australians have experienced 1.5 million disaster exposures to natural disasters alone.1 General practitioners are a widely dispersed, inevitably involved medical resource who have the capacity to deal with both emergency need and long-term disaster-related health concerns. Despite the high likelihood of spontaneous involvement, formal systems of disaster response do not systematically include GPs.

An Australian Government review of the national health sector response to pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza suggested: “General practice had a larger role than had been considered in planning”.2 It commented that “structures . . . in place to liaise with, support and provide information to GPs were not well developed”; personal protective equipment provision to GPs was “a significant issue”; and planned administration of vaccinations through mass vaccination clinics was instead administered through GP surgeries.2

GPs are well positioned to help

As of the financial year 2013–14, Australia had 32 401 GPs,3 distributed through rural and urban communities. GPs are onsite with local knowledge when disaster affects their communities. External assistance may be delayed, and the local doctor may be integral in initial community response and feel compelled to act, yet have a poorly defined role.

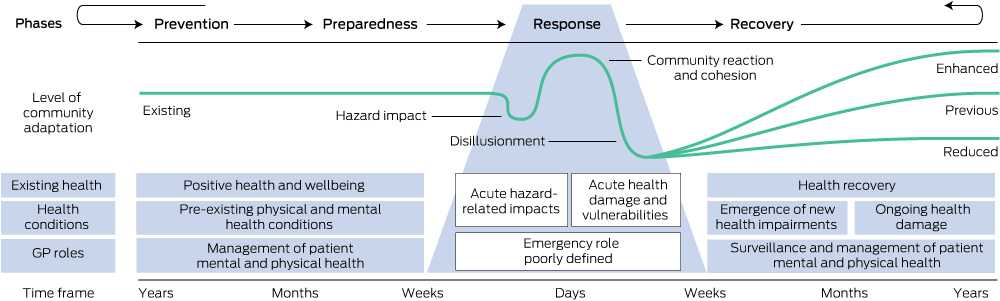

GPs can identify vulnerable community members, and are situated in local medical infrastructure with medical resources. When other agencies withdraw in the months after disaster, GPs remain, providing continuity of care, which is likely to be important at this time of high distress and medical need (Box 1). Primary health care during extreme events can support preparedness, response and recovery, with the potential to improve health outcomes.4 The challenge lies in linking GPs with the existing medical assistance response.

Australian GPs’ experience of responding to disasters

Australian GPs have a strong sense of responsibility and moral obligation to their patients. They have spontaneously demonstrated willingness and capacity to respond in recent disasters, including the 2011 Australian floods, the 2009 pandemic influenza, and recent bushfires. In interviews with 60 Tasmanian GPs, 100% of GPs surveyed intended to contribute to patient care in the event of a pandemic, with expression of a strong sense that to do otherwise was unethical, although this was dependent on provision of appropriate personal protective equipment.5

What is lacking is consistent support for GPs, their families and their practices. Local GPs may be personally affected and immersed in the disaster, or experience repetitive exposure to their patients’ trauma. Changes in patient presentations, workload, income and working conditions create additional stress, particularly if compounded by personal loss or injury.6 GPs involved in ad hoc spontaneous response may experience uncertainty of their role or efficacy, reluctance to stand down, or may prefer no involvement. GPs interviewed after the 2011 Christchurch earthquake noted experiencing “emotional exhaustion” and physical fatigue; some were aware of the need for personal care at the time, and others only in retrospect.6

Principles of disaster management

The principles of disaster management follow the internationally accepted all-hazards, all-agencies approach through the phases of prevention, preparedness, response and recovery (PPRR).7 Despite the variation in GP roles due to practice locations and context, the GP role in disaster management is most evident across the time frames of PPRR. As shown in Box 1, GPs provide continuity of care across these periods, but with the least consistency in the response phase.

Preparedness

Our discussions with key GP groups and leaders in the field suggest that despite a rapid increase in the number of practices engaging in disaster planning over the past year, most GPs are currently underprepared for disasters (Box 2). Lack of preparedness increases vulnerability. To redress this global problem, the World Medical Association recommends disaster medicine training for medical students and postgraduates. This could include education on existing disaster response systems, mass casualty triage skills, psychological first aid and the epidemiology of disaster morbidity in the first instance.

Response

In the response phase, it is important that GPs are aware of the overarching plan following the incident management system that coordinates multiple disciplines (including fire, police, ambulance and health) to respond to all types of emergencies, from natural disasters to terrorism. With this in mind, roles for GPs have previously included accepting patients from a neighbouring affected practice, assisting at other practices or with surges in hospital emergency department presentations and at GP after-hours services, or keeping patients out of hospitals through “hospital in the home” services. It may involve providing prescriptions and medical treatment in an evacuation centre, being included in medical teams such as St John Ambulance or identifying more vulnerable patients for evacuation assistance. Most importantly, GPs should maintain usual practice activities where possible. These response models are aligned with the range of GP skills and have clear operational requirements.

Recovery

GP involvement is imperative in the recovery phase, ensuring continuity of physical and psychosocial health care during the ensuing months to years. While most patients recover with minimal assistance, it is crucial that individuals in need of increased support are recognised, particularly those with pre-existing chronic disease. Some presentations may be related to particular hazards, eg, smoke inhalation after bushfire, but many others are risks regardless of the hazard. These include increased substance use, anxiety, depression, acute or post-traumatic stress disorder, chronic disease deterioration, and the emergence of new conditions, including hypertension, ischaemic heart disease and respiratory conditions.8 Children are particularly vulnerable, and changes in behaviour or school performance may indicate residual problems.

Support from general practice organisations (GPOs)

During the 2009 Victorian bushfires, Divisions of General Practice provided strong support to enable general practices affected by the fires to continue to offer health care, by providing human and material resources, skills training, advocacy and media liaison. During the 2013 New South Wales bushfires, there was strong GP linkage by the Nepean-Blue Mountains Medicare Local to existing systems through the Nepean Blue Mountains Local Health District and the state health emergency operations centre, as well as to GPOs at a state level. Lessons learnt need to be incorporated into systems planning.

The need for unified disaster planning is increasingly recognised at both individual GP and GPO levels. The General Practice Roundtable, with input from all the major GPOs, has diverse GP representation, providing an opportunity for broad input into disaster planning across PPRR. Important recent initiatives by GPOs include position statements for GPs,9 and ongoing development of disaster resources, promotion of general practice disaster planning, and the recent formation of a national Disaster Management Special Interest Group within the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners.

Where to from here?

Disasters are devastating events and by nature are unpredictable. While recognising and acknowledging the critical role of the formal emergency response agencies in the existing system of specialised health response and management, the strength of general practice lies in the provision of comprehensive continuity of care, and this lends itself to greatest involvement in the preparedness and recovery phases. There is a need for a clear definition of roles in the response stage. GPs as local medical providers in disaster-affected communities need to be systematically integrated into the existing stages of PPRR with clear responsibilities, lines of communication, and support from GPOs, avoiding duplication of other responders’ tasks. Valuing and using the expertise and resources that GPs can bring to disasters may improve long-term patient and community health outcomes.

2 Potential roles for general practitioners and GP-related groups in disasters

Prevention and preparedness — before the disaster

- national position on the role of GPs in disasters across PPRR;

- clearly defined roles that integrate with other responding agencies;

- GPO representation on national, state and local disaster management committees;

- unified disaster planning across GPOs through the GPRT;

- information for other agencies on GPs’ skills and roles through the GPRT and GPOs;

- education and training in core aspects of disaster medicine for GPs and medical students;

- involvement of local GPs in local disaster planning and exercises through ML or PHN;

- general practice business continuity and disaster response practice planning;

- assisting patient preparedness to reduce vulnerability;

- GP personal and family preparedness; and

- vaccination, infection control measures and surveillance in infectious events.

Response — during the disaster

- representation in EOCs for communication and coordination with other responders (including ambulance, mental health, public health, etc);

- unified disaster response from GPOs, including information, resources and phone support;

- coordination through GP networks for workforce support for affected practices;

- clearly defined integrated roles in existing systems for GPs involved in response, such as:

- maintaining usual practice activities where possible to help surge capacity

- expanding practice capacity to treat extra patients if needed

- expanded use of practice infrastructure, medical resources and trained staff as appropriate

- supporting existing medical teams such as St John Ambulance

- assisting at the scene, evacuation centre or local clinic as appropriate;

- assistance in identification of potentially vulnerable and at-risk individuals and families;

- ongoing communication with and referral between other local primary care health providers;

- patient education on hazard-related health matters, eg, asbestos, infectious outbreaks, etc;

- preventive vaccination — tetanus (clean-up injuries); and

- surveillance for future outbreaks and emerging community disease threats.

Recovery — after the disaster

- inclusion in the review process to improve future PPRR;2

- representation on recovery committees to improve interagency referral and communication;

- ongoing support from GPOs for affected GPs and staff through regular contact and resources;

- GPOs and ML or PHN support for those practices that are more affected;

- management of deterioration of pre-existing physical and mental health conditions;

- surveillance for new physical and psychological conditions to improve patient outcomes;

- surveillance for emerging community disease threats; and

- linkage and communication with community groups and allied health on recovery activities.

EOC = emergency operations centre. GPO = general practice organisations. GPRT = General Practice Roundtable. ML = Medicare Locals. PHN = Primary Health Networks. PPRR = prevention, preparedness, response and recovery.

more_vert

more_vert