Social media are defined as a group of internet-based applications that allow the creation and exchange of user-generated content within a virtual community or network.1 Their rapid growth over the past decade has caused a paradigm shift in the way people communicate. The social media service Facebook reported 1.19 billion active users in 2013, and as early as 2008 the site was used by 64% of medical students,2 increasing to 93% of Australian first-year health professional students in 2013,3 suggesting that Facebook and other social media services form a growing part of students’ lives.

Earlier research has examined the use of social media by medical students and doctors for personal purposes and discussed the implications for medical professionalism.4 One study5 explored American medical schools’ experience of medical students posting improper content online, including profanity, discriminatory language, depictions of alcohol intoxication, and sexually suggestive material. Such cases have led to disciplinary action and even expulsion.6 In response to the growing use of social media and concerns about its effect on professionalism, the Australian Medical Association published a guideline on online professionalism for medical students and practitioners in 2010.7

Some behaviours are clearly unprofessional, such as the posting of patient information or any content that involves illegal activity. Depending on the context, depicting alcohol use may also be unprofessional.

We hypothesised that social media usage would be high among medical students, and that unprofessional material would be commonly posted and publicly available online. Additionally, we anticipated that medical students would know the relevant guidelines,7,8 and that they would moderate their online behaviour accordingly.

The aim of our study was to assess social media use patterns among medical students, and to identify factors independently associated with reporting evidence of unprofessional behaviour on social media. We specifically investigated whether being exposed to guidelines on social media professionalism was associated with reduced prevalence of such behaviours.

Methods

An online survey comprising 35 questions with a skip-logic design was developed using the SurveyGizmo platform. Not every question was put to every respondent, as not all were applicable. The survey was conducted between 29 March and 12 August 2013.

Any student who was currently enrolled in a medical degree (undergraduate or postgraduate) at an Australian university was eligible to respond; 16 993 students were potentially eligible, including international students.9 Students were recruited by contacting student organisations and Australian Medical Students Association (AMSA) representatives from each medical school and asking them to disseminate the recruitment information. The assistance of medical school deans was sought for internal promotion of the survey on online learning management systems (eg, Blackboard and Moodle). The study was also promoted by these groups through Facebook and Twitter.

A standard consent page that detailed the purpose of the study was displayed before the survey was delivered. All responses were recorded, although only complete responses were included in the final analysis. As an incentive to complete the survey, students were offered the chance to win a prepaid debit card to the value of $500, to be allocated randomly to one respondent; contact details were collected for this purpose in a separate form to ensure that identifying details could not be linked to the survey data. Vendor-provided duplicate protection technologies were used to prevent multiple responses by an individual. Funding was not received from any external body, with all costs borne by the authors of this article.

“Unprofessional content” was defined as an online depiction of illegal activity, overt intoxication or illicit drug use, or the posting of patient information. If students had removed unprofessional content posted by themselves or others on their account, it was not assessed as evidence of unprofessional behaviour.

Data were exported from the platform and analysed with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute). Univariate comparisons were performed using χ2, Student t– and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests as appropriate, according to the type and distribution of the data. Parametric data are reported as means and standard deviations, non-parametric data as medians with interquartile ranges (IQR), and categorical variables as numbers and percentages. Multivariable logistic regression of “unprofessional behaviour” was performed using backwards elimination techniques, with univariate P < 0.25 as the cut-off for inclusion; results are reported as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals. Multicollinearity was assessed by evaluating coefficient changes between univariable and multivariable models and using variance inflation factors. P < 0.05 (two-sided) was defined as statistically significant.

The study was approved as a low-risk project by the Monash Health Research Ethics Committee (MUHREC LR 2012001495).

Results

It was not known how many of the 16 993 students enrolled at Australian medical schools received notification about the survey, but 1027 from 20 medical schools (21 at the time of study enrolment) initially responded. Of these, 880 students fully completed the survey (85.6%) and thus comprised the study cohort.

Of the 880 students who submitted complete responses, 534 (60.6%) were undergraduates, 391 (44.4%) were from Victorian medical schools, and 875 (99.4%) used Facebook. The next most commonly used social networks were YouTube (853 students, 96.9%) and blogging platforms (399 students, 45.3%). Every student used at least one social network, with a mean of 5.5 networks per student (95% CI, 5.31–5.67). Online professionalism teaching had been received by 305 students (34.9%). Other demographic data are included in Box 1.

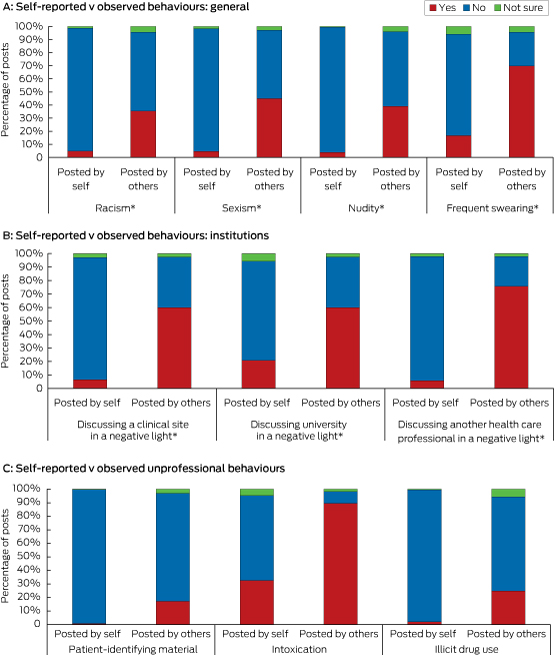

Unprofessional content was reported by 306 students as (34.7%) being present on their accounts. Evidence of intoxication was reported by 301 students (34.2%), evidence of illegal drug use by 14 (1.6%), depiction of an illegal act by 10 (1.1%), and the posting of patient information by 14 (1.6%). The proportion of students who reported seeing unprofessional content on other medical students’ accounts was much higher than that of those who reported it being present on their own account (Box 2).

Most students were aware of social media guidelines, with 475 (53.9%) aware of a professional body guideline, 363 (41.2%) of a university or clinical school guideline, and 584 (66%; 95% CI, 63%–69%) of at least one of the two. There was no association between knowledge of social media guidelines and unprofessional behaviour on social media (OR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.54–1.11; P = 0.16). Most respondents (796, 90.5%) agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that they were held to a higher standard of professionalism than the general community; 27 (3.1%) disagreed and four (0.5%) strongly disagreed (Box 3 and Box 4).

Of the 875 students who used Facebook, 848 (96.9%) had changed the default security settings and 744 (85.0%) had a private profile; 618 students (70.6%) had increased their privacy and security settings by restricting content to groups or specific individuals.

After adjusting for covariates, unprofessional content was associated with students reporting that they had posted to their accounts evidence of alcohol use (OR, 6.50; 95% CI, 4.42–9.56; P < 0.001) or racist content (OR, 2.45; 95% CI, 1.15–5.20; P = 0.02), that they had used MySpace (OR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.09–2.1; P = 0.01), and planned to change their profile name after graduation (OR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.12–2.31; P = 0.01). Behaviours less likely to be associated with reporting of unprofessional content included believing that videos depicting medical events with heavy alcohol use are inappropriate (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.63–0.85; P < 0.001), and being happy with their social media portrayal (OR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.45–0.74; P < 0.001) (Box 4). Exposure to guidelines had no effect on students reporting unprofessional behaviours. The act of completing the survey itself caused 493 students (56.0%) to check their privacy settings, and 307 (34.9%) to change them.

Discussion

Our study found that social media use by the study population of medical students was nearly universal; further, 34.7% of respondents reported evidence of unprofessional content on their accounts. More students reported viewing unprofessional content on other students’ accounts than on their own. Unprofessional content was reported despite exposure to guidelines and education about online professionalism.

Medical students are held to higher standards of professionalism than general university students, and we found that most students are aware of this. This is relevant, as unprofessional conduct (online or offline) by a student may lead to disciplinary action, and has also been found to be associated with lapses during later professional practice.6,10

Factors associated with unprofessional content

Several factors were associated with the presence of unprofessional content, including evidence of alcohol use or racist content, and planning to change one’s profile name after graduation. Conversely, being happy with their social media portrayal appears to reduce the posting of unprofessional content by students. The implications of the association of unprofessional content with MySpace use are uncertain, and may now be weaker, given the decline in use of this platform.

The association between posting unprofessional content and the intention to change social media profile names on graduation suggests that students were aware that they had unprofessional content on their accounts but were not intending to remove it. This is despite knowing about the relevant guidelines and believing they are subject to a higher expectation of professionalism than the general public. As changing one’s profile name may not effectively conceal an individual’s identity, such strategies provide a false sense of security and, paradoxically, encourage unprofessional behaviour.11

Professionalism guidelines

Medical associations and professional organisations have published guidelines and other literature7,8 in response to earlier research and reports in the media. Our results suggest that, despite the widespread dissemination and awareness of professional body guidelines in Australia, there appears to have been only a minimal impact on medical students’ behaviour.

There is a distinction between disseminating guidelines and formally integrating social media instruction into medical curricula. Senior clinicians and teachers who have not used social media may teach professionalism “largely in the context of the physician–patient relationship”,12 and be ill-equipped for teaching their juniors about professionalism in a social media context.13 Our findings show that reducing the unprofessional use of social media will require more than providing guidelines.

Privacy settings

The finding that 71% of students who used Facebook had set their account to “private” was higher than the 37.5% among US medical students reported in a 2008 study.2 Private profiles allow a medical student to partition “personal” information from their public persona. However, they do not provide a completely safe sanctuary for unprofessional behaviour. Data leaks, changes to terms and conditions, and public dissemination of previously private information mean that private content posted to social media may still become more widely available.

Reading and interpreting online content is highly subjective, and the level of professionalism expected in both public and private spaces varies between individuals. Completing the survey led 35% of students to adjust their privacy settings, suggesting that being prompted to do so, combined with their reflecting on a desirable public image, may be an effective intervention. The higher proportions of participants who reported having seen rather than posted unprofessional behaviour also highlight an intrinsic attribute of social networks: that a single example of unprofessional content may be seen by a large number of medical students. While use of a private profile may not reduce the incidence of unprofessional content, it does reduce the size of the potential audience for that content.

Strengths and limitations

There are some limitations to our study. Participation was voluntary, and many participants were recruited through social media; each factor introduces selection bias. Our survey included only a small proportion of the 16 993 Australian medical students in 2013; we were unable to estimate the number of students who were actually aware of the study. A large proportion of participants were from a small number of Victorian universities, the state in which the authors of this article reside, and this may limit extrapolation of the results to other medical student populations. The survey was conducted in 2013, and the time that has elapsed between collecting and publishing our data is also acknowledged.

Our study relied on the self-reporting of specific content on social media, and did not record the prevalence of unprofessional behaviour itself. This has the potential for introducing both information and recall bias, as students may report their own behaviour differently to their perception of others’. In addition, the accuracy of participants’ responses could not be verified. The findings of this study cannot be extrapolated to qualified medical practitioners or to other allied medical staff.

Nevertheless, our study is the largest to examine medical student professionalism on social media, and has identified factors that may predict and protect against future unprofessional behaviour. It also showed that the act of completing the study was sufficient to change some behaviours, so that introspection itself may be a beneficial tool for educators seeking to address this problem.

Conclusion

The use of social media by the surveyed students was almost universal, and unprofessional behaviours on social media were exhibited by a significant proportion of medical students, despite widespread awareness of guidelines about professionalism. Content posted online is effectively in the public domain, and management of their online identity is therefore now part of a student’s professional responsibility. Medical educators should consider approaches beyond simply providing guidelines or policies, and students should be regularly prompted to reflect on their activities, to evaluate their online behaviours, and to temper them if appropriate.

Box 1 –

Demographic characteristics of students reporting or not reporting evidence of unprofessional behaviour∗

|

All students

|

Students reporting no evidence of unprofessional behaviour

|

Students reporting evidence of unprofessional behaviour

|

P

|

|

|

Number

|

880

|

574

|

306

|

|

|

Median age (IQR), years

|

22 (20–24) [range, 16–40]

|

22 (20–24)

|

22 (21–24)

|

0.95

|

|

Enrolment type

|

|

|

|

|

|

Undergraduate

|

534 (60.6%)

|

359 (67.4%)

|

174 (32.6%)

|

0.11

|

|

Previous health care degree†

|

98 (28%)

|

66 (67%)

|

32 (33%)

|

0.65

|

|

Domestic‡

|

826 (94.1%)

|

527 (63.8%)

|

299 (36.2%)

|

0.001

|

|

Year of study

|

|

|

|

|

|

1st

|

184 (20.9%)

|

122 (13.9%)

|

62 (7.0%)

|

0.79

|

|

2nd

|

173 (19.7%)

|

117 (13.3%)

|

56 (6.4%)

|

0.48

|

|

3rd

|

189 (21.5%)

|

124 (14.1%)

|

65 (7.4%)

|

0.93

|

|

4th

|

169 (19.2%)

|

103 (11.7%)

|

66 (7.5%)

|

0.21

|

|

5th

|

93 (10.6%)

|

55 (6.3%)

|

38 (4.3%)

|

0.21

|

|

6th

|

71 (8.1%)

|

53 (6.0%)

|

18 (2.1%)

|

0.09

|

|

University attended

|

|

|

|

|

|

Monash (Victoria)

|

278 (31.6%)

|

190 (21.6%)

|

88 (10.0%)

|

0.19

|

|

Western Australia

|

116 (13.2%)

|

73 (8.3%)

|

43 (4.9%)

|

0.60

|

|

Melbourne (Victoria)

|

113 (12.8%)

|

79 (8.9%)

|

34 (3.9%)

|

0.29

|

|

Deakin (Victoria)

|

78 (8.9%)

|

49 (5.6%)

|

29 (3.3%)

|

0.71

|

|

Queensland

|

48 (5.5%)

|

30 (3.4%)

|

18 (2.0%)

|

0.75

|

|

New England (NSW)

|

48 (5.5%)

|

25 (2.8%)

|

23 (2.6%)

|

0.06

|

|

Western Sydney (NSW)

|

39 (4.4%)

|

29 (3.3%)

|

10 (1.1%)

|

0.30

|

|

Others

|

160 (18.1%)

|

99 (61.9%)

|

61 (38.1%)

|

0.36

|

|

Received instruction about online professionalism

|

|

Yes

|

305 (34.9%)

|

199 (22.8%)

|

106 (12.1%)

|

0.45

|

|

No

|

421 (48.2%)

|

268 (30.7%)

|

153 (17.5%)

|

|

|

Not sure

|

147 (16.8%)

|

102 (11.7%)

|

45 (5.2%)

|

|

|

|

∗ All values reported as number (and column percentage) unless otherwise stated. † Percentage refers to medical postgraduates only. ‡ Australian and New Zealand citizens, and Australian permanent residents.

|

Box 2 –

Unprofessional behaviours on medical students’ social media accounts, self-reported (own account) v observed (others’ accounts)

Box 3 –

Characteristics of students reporting or not reporting evidence of unprofessional behaviour∗ (univariate analysis)

|

Students reporting no evidence of unprofessional behaviour

|

Students reporting evidence of unprofessional behaviour

|

P

|

|

|

Do you use:

|

|

|

|

|

Facebook

|

566/567 (99.8%)

|

304/305 (99.6%)

|

1.0

|

|

Twitter

|

208/574 (36.2%)

|

145/306 (47.4%)

|

0.002

|

|

Reddit

|

107/574 (18.6%)

|

93/306 (30.4%)

|

0.01

|

|

Do you think it is appropriate to be Facebook “friends” with:

|

|

|

|

|

Allied health staff

|

333/570 (58.4%)

|

213/302 (70.5%)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Junior doctors

|

443/571 (77.6%)

|

263/304 (86.5%)

|

0.0016

|

|

Nurses

|

322/568 (56.7%)

|

209/303 (70.0%)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Patients’ families

|

17/570 (3.0%)

|

7/303 (2.3%)

|

0.67

|

|

Patients

|

12/570 (1.38%)

|

3/303 (0.34%)

|

0.33

|

|

Have you ever posted content which could be interpreted as:

|

|

|

|

|

Racist

|

16/566 (2.8%)

|

25/302 (8.3%)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Sexist

|

225/568 (39.6%)

|

166/301 (55.2%)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Containing frequent swearing

|

58/569 (10.2%)

|

91/301 (30.2%)

|

< 0.001

|

|

Discussing a clinical site in a negative light

|

88/568 (15.5%)

|

93/302 (30.8%)

|

< 0.001

|

|

What guides your professionalism on social media?

|

|

|

|

|

Concerns about appearing unprofessional to friends, family, or peers

|

407/574 (70.9%)

|

192/306 (62.8%)

|

0.01

|

|

Belief that as a medical student I am held to a higher standard of professionalism

|

522/570 (91.6%)

|

274/304 (90.1%)

|

0.53

|

|

University social media guidelines or policy guides my behaviour

|

148/574 (25.8%)

|

58/306 (19.0%)

|

0.02

|

|

Concern about appearing unprofessional to general public

|

414/574 (72.1%)

|

198/306 (64.7%)

|

0.03

|

|

Do you believe professionalism extends to social media presence?

|

516/568 (90.8%)

|

246/306 (80.4%)

|

0.0001

|

|

Do you feel you have control over social media portrayal?

|

454/567 (80.1%)

|

218/303 (71.9%)

|

0.008

|

|

Are you happy with your social media portrayal?

|

504/569 (88.6%)

|

228/305 (74.7%)

|

0.0001

|

|

Do you use a pseudonym for your profile name?

|

46/566 (8.1%)

|

40/306 (13.1%)

|

0.02

|

|

Do you plan to change your Facebook profile name after graduation?

|

138/574 (24.0%)

|

110/306 (36.0%)

|

0.0001

|

|

Are you a domestic student?

|

527/572 (92.1%)

|

299/306 (97.7%)

|

0.0008

|

|

Have you read or been instructed about a social media guideline?

|

412/574 (71.8%)

|

219/306 (71.7%)

|

0.95

|

|

|

∗ All values reported as number and percentage of responders.

|

Box 4 –

Reported factors independently associated with unprofessional behaviours (multivariate analysis)

|

OR (95% CI)

|

P

|

|

|

Evidence of any alcohol use (not intoxication)

|

6.50 (4.42–9.56)

|

< 0.0001

|

|

Evidence of posting racist content

|

2.45 (1.15–5.20)

|

0.02

|

|

MySpace use

|

1.61 (1.09–2.10)

|

0.01

|

|

Planning to change profile name upon graduation

|

1.61 (1.12–2.31)

|

0.01

|

|

Believing that recording videos of medical events depicting heavy alcohol use are inappropriate

|

0.73 (0.63–0.85)

|

< 0.0001

|

|

Happy with social media portrayal

|

0.57 (0.45–0.74)

|

< 0.0001

|

|

Read or been educated on social media guidelines

|

0.77 (0.54–1.11)

|

0.16

|

|

|

OR = odds ratio. Hosmer–Lemeshow H statistic for goodness of fit, 5.31; P = 0.72; area under receiver–operator characteristic curve, 0.80.

|

more_vert

more_vert