Iran’s health system has undergone several reforms in the past three decades with many challenges and successes. The most important reform was the establishment of the National Health Network in 1983, which aimed to reduce inequities and expand coverage and access to health care in deprived areas.1 The Iranian Government has since implemented several other reforms, such as the Family Physician Programme, integration of health services and medical education, the hospital autonomy policy, and the Health Sector Evolution Plan, all of which have had benefits and disadvantages.

Preference: Education

190

[Obituary] Naeem Aon Jafarey

Pathologist and medical educationist. He was born on May 4, 1929, in Allahabad, India, and died of a brain cancer on Nov 2, 2015, in Karachi, Pakistan, aged 86 years.

[Correspondence] Coca-Cola’s multifaceted threat to global public health

The Lancet Editorial (Oct 3, p 1312) correctly identified that Coca-Cola’s goals differ greatly from those of the public health and research institutions that it funds.1 All organisations concerned with public interest need to guard against conflict of interest from Coca-Cola’s vast marketing campaigns to safeguard public health. One such marketing campaign involves advertisements at public schools in Uganda (figure), which illustrates Coca-Cola’s predatory use of corporate funding, in the name of “corporate social responsibility”, to target children in a setting of inadequate public funding for education.

Female doctors in Australia are hitting glass ceilings – why?

Over the past 30 years, there have been some great achievements in gender equity. The number of women enrolled in professional degrees, such as law and medicine, rose from less than 25% in the 1970s to more than 50% in 2015. Australia has introduced a number of equal opportunity policies in health care and in 2000 achieved gender parity in medical schools.

Today, women are typically the dominant group within medical schools and yet remain under-represented in formal leadership positions and particular speciality areas. Although today there is greater female participation in medical roles, it still appears that women are hitting the glass ceiling.

Similar sorts of trends in gender participation are found in other countries such as the UK, Canada and the US. Given these broader trends, we could infer that these patterns are the result of “natural” processes related to the relative merits of the sexes.

Yet studies in Sweden show remarkably similar preferences for speciality areas across male and female medical students. Like Australia, these preferences have not typically translated into representation across the health workforce. This suggests there are forces in place that mean women do not go into their preferred roles.

Women in leadership

Despite the significant representation of women within the medical workforce, today fewer than 12.5% of hospitals with more than 1000 employees have a female chief executive. 28% of medical schools have female deans. 33% of state and federal chief medical officers or chief health officers are female.

In 1986, fewer than 16% of specialists were women. This rose to 34% in 2011.

While this is a substantial increase, women are also woefully underrepresented in these figures. There are also distinct gender patterns across specialist roles. Women’s participation is skewed towards pathology (58%), paediatrics (53%), obstetrics and gynaecology (49%) and underrepresented in orthopaedic surgery (6%), vascular surgery (11%) and cardiothoracic surgery (12%).

A popular explanation for these patterns is that there is a lag phenomenon at play. Once current women advance through their career, figures will self-correct and result in more gender balance in the system.

A more pessimistic view (and one we would subscribe to) is that women are being channelled into particular areas of the profession that are lower status and attract lower pay, while more high-profile roles remain in the hands of men.

This is not to say that male doctors are (all) actively working to keep women excluded from these roles. There are a range of reasons for the barriers around perceptions of capability, capacity and credibility.

Capability, capacity, credibility

The evidence suggests that women are as (and possibly more in some cases) intellectually capable of the high-profile roles that they are poorly represented in.

Our research found that some women may lack self-confidence or doubt their ability to undertake certain roles. What this means is that women may be less willing to self-promote or to put themselves forward for positions traditionally held by men.

Women are more likely than men to have caring responsibilities, which can have implications for perceived capacity. Juggling leadership or the long hours associated with some speciality areas with motherhood can be a challenge.

Many of the areas where women are poorly represented in offer limited options for flexible ways of working and cultivating work-life balance. Some speciality areas have additional years of training which, again, can make them difficult to access for some women.

Perceived credibility is a further barrier, with women not being taken seriously as leaders or surgeons – roles typically associated with males. Sociology has a long tradition of scholarship arguing that organisations and professions are highly gendered and valorise masculine values.

Where work environments are heavily gendered, they can be alienating for some women. Some speciality areas are traditionally considered to be highly male (think surgery) in a way that paediatrics or palliative care may be less so.

These barriers are not simply externally imposed on women by men and may be internalised in women through the broader culture and values of organisations. Internalised beliefs about the traits and qualities required for particular roles can dissuade some women from actively seeking out these roles, unless they received mentoring and support from others.

At an interpersonal level, unconscious biases, sexist micro-aggressions, and a “club culture” contribute to a hostile environment for women within some health-care settings. At a structural level, conservative social norms and male-dominated career pathways can make it difficult for women to balance the pressures and demands of maternity leave, child-rearing, care-giving and running a household with leadership roles.

What is clear is that with such a broad range of barriers, there will be no easy or quick solutions. If we are to successfully smash these glass ceilings then solutions will need to be structural as well as cultural. Women will be unable to overcome these issues alone and solutions will need to be both multifaceted and supported through a broad base.

![]()

Helen Dickinson, Associate Professor, Public Governance, University of Melbourne and Marie Bismark, Senior Research Fellow, Public Health Law, University of Melbourne

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Other doctorportal blogs

[Correspondence] India’s medical education system hit by scandals

We read with interest Dinesh Sharma’s report (Aug 8, p 517)1 on scandals in the Indian medical education system. We wish to comment on and suggest reforms that could result in change.

‘Why does this Government have it in for sick people?’

AMA President Professor Brian Owler has accused the Federal Government of ‘having it in’ for the ill over its plan to scrap bulk billing incentives for pathology services and downgrade them for diagnostic imaging.

As Health Minister Sussan Ley admitted some patients “may be worse off” as a result of the changes announced in the Mid Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, Professor Owler warned they would increase expenses for patients and amounted to a “co-payment by stealth”.

“I really don’t understand why this Government has it in for sick people,” he told Channel Nine.

The AMA President said the Government’s decision to save around $300 million by axing bulk billing incentives for pathology services would force many providers, who haven’t had their Medicare rebate indexed for 17 years, to introduce a charge for patients.

“That is why it is a co-payment by stealth,” Professor Owler told ABC radio. “It’s about forcing providers to actually pass on those costs to their patients.

“So, while Tony Abbott might have said that the co-payments plans was dead, buried and cremated, it seems to have made a miraculous recovery and it’s reaching out from beyond the grave – or, at least, components of it are.”

Treasurer Scott Morrison has denied the claim, and Health Minister Sussan Ley said competition in the pathology industry would ensure increased costs were absorbed by providers rather than being passed on to patients.

In an interview on ABC radio she initially claimed there were 5000 providers operating in a “highly corporatised and highly competitive” environment.

She later clarified her comments, admitting that there were 5000 collection centres rather than individual operators, and most were owned by “two very large corporate entities and they’re doing very nicely.”

Ms Ley said the charging practices of providers was a commercial decision and “we can’t dictate what they charge patients”.

But Professor Owler said it was “completely ridiculous” for the Government to pretend its cuts would not result in charges for patients.

“You can’t take out what is essentially over $300 million from pathology and not expect that there’s going to be some sort of effect on patients,” he said. “Without that money being supplied to those providers, of course they’re going to have to charge the patients and so you’re going to see more patients with more out of pocket expenditure.

“And that is the plan of this Government – to pass more expense on to the pockets of the patients, and that is going to affect the sick and the most vulnerable in our community.”

In addition to axing and downgrading bulk billing for pathology and diagnostic imaging services, the Government expects a further $595 million will be saved by “streamlining” health workforce funding, including dumping several programs including the Clinical Training Fund (which was originally intended to fund up to 12,000 clinical training places across a range of disciplines), the Rural Health Continuing Education Program, the Aged Care Education and Training Initiative and the Aged Care Vocational Education and Training professional development program.

The Federal Government is also tapping the aged care sector for significant savings. It plans to cut more than $480 million by improving the compliance of aged care providers and making revisions to the Aged Care Funding Instrument Complex Health Care Domain.

The Government also expects to realise $146 million in savings from improving the efficiency of health programs, and plans to extract $78 million from the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority and $104 million from the National Health Performance Authority.

A further $31 million will be withdrawn from public hospital funding over the next four years.

Professor Owler said the health sector needed more detail and explanation from the Government regarding the MYEFO cuts.

“All up, MYEFO has delivered another significant hit to the health budget with services and programs cut, and more costs being shifted on to patients,” he said.

The health savings have been announced as part of measures to help improve the Budget, which has been rocked by a plunge in revenues caused by soft economic activity and falling commodity prices.

Since May, the Budget deficit has swelled by more than $2 billion to $37.4 billion, and is expected to be $26 billion bigger than anticipated over the next four years. Mr Morrison has targeted social services and health to deliver the bulk of spending cuts needed to put the Budget on the path to a surplus, which has been pushed back to 2020-21.

But the tenuous nature of this goal has been underlined by the fact that the Government is relying on savings measures that have little prospect of being implemented to help achieve the surplus.

In particular, proposed changes to the Medicare Safety Net worth $267 million were withdrawn by Ms Ley earlier this month after failing to garner sufficient support in the Senate, but still included in the Budget.

While the Government targeted health for major cuts, it did announce some initiatives welcomed by the AMA, including $131 million to expand the Rural Health Multidisciplinary Training Program and establish grants for private healthcare providers to support undergraduate medical places, and a further $93.8 million to develop an integrated prevocational medical training pathway in rural and regional areas – a measure the AMA has long been advocating for.

The Government has also introduced new MBS items for sexual health and addiction medicine services.

Adrian Rollins

‘Everything presents at extremes…’ – a Solomon Islands experience

Pictgure: Dr Elizabeth Gallagher (second from left) with other staff and volunteers at the National Referral Hospital, Honiara

By Dr Elizabeth Gallagher, specialist obstetrician and gynaecologist, AMA ACT President

The mother lost consciousness just as her baby was born.

The woman was having her child by elective Caesarean when she suffered a massive amniotic fluid embolism and very quickly went into cardiac arrest.

We rapidly swung into resuscitation and, through CPR, defibrillation and large doses of adrenaline, we were able to restore her to unsupported sinus rhythm and spontaneous breathing.

But, with no equipment to support ventilation, treat disseminated intravascular coagulation, renal failure or any of the problems that arise from this catastrophic event, it was always going to be difficult, and she died two-and-a-half hours later.

Sadly, at the National Referral Hospital in Honiara, the capital of the Solomon Islands, this was not an uncommon outcome. Maternal deaths (both direct and indirect) average about one a month, and this was the second amniotic fluid embolism seen at the hospital since the start of the year.

I was in Solomon Islands as part of a team of four Australian practitioners – fellow obstetrician and gynaecologist Dr Tween Low, anaesthetist Dr Nicola Meares, and perioperative nurse and midwife Lesley Stewart – volunteering to help out at the hospital for a couple of weeks in October.

It was the first time I had worked in a developing country, and it was one of the most challenging, and yet satisfying, things I have ever done

Everything from the acuteness of the health problems to the basic facilities and shortages of equipment and medicines that we take for granted made working there a revelation.

The hospital delivers 5000 babies a year and can get very busy. As many as 48 babies can be born in a single 24-hour period.

The hospital has a first stage lounge and a single postnatal ward, but just one shower and toilet to serve more than 20 patients. The gynaecology ward is open plan and, because the hospital doesn’t provide a full meal service or much linen, relatives stay there round-the-clock to do the washing and provide meals.

From the beginning of our stay, it was very clear that providing training and education had to be a priority. I was conscious of the importance of being able to teach skills that were sustainable once we left.

The nature of the emergency gynaecological work, which includes referrals from the outer provinces, is that everything presents at the extremes…and late. Massive fibroids, huge ovarian cysts and, most tragically because there is no screening program, advanced cervical cancers in very young women.

When I first got in touch with doctors at the hospital to arrange my visit, I had visions of helping them run the labour ward and give permanent staff a much-needed break. But what they wanted, and needed, us to do was surgery and teaching.

To say they saved the difficult cases up for us is an understatement. I was challenged at every turn, and even when the surgery was not difficult, the co-morbidities and anaesthetic risks kept Dr Meares on her toes.

In my first two days, the hospital had booked two women – one aged 50 years, the other, 30 – to have radical hysterectomies for late stage one or early stage two cervical cancer. I was told that if I did not operate they would just be sent to palliation, so I did my best, having not seen one since I finished my training more than 12 years ago.

I also reviewed two other woman, a 29-year-old and a 35-year-old, both of whom had at least a clinical stage three cervical cancer and would be for palliation only. This consisted of sending them home and telling them to come back when the pain got too bad.

It really brought home how effective our screening program is in Australia, and how dangerous it would be if we got complacent about it.

We found the post-operative pain relief and care challenged. This was because staffing could be limited overnight and the nurses on duty did not ask the patients whether they felt pain – and the patients would definitely not say anything without being asked.

Doing our rounds in our first two days, we found that none of the post-operative patients had been given any pain relief, even a paracetamol, after leaving theatre.

We conducted some educational sessions with the nursing staff, mindful that the local team would need to continue to implement and use the skills and knowledge we had brought once we left. By the third day, we were pleased to see that our patients were being regularly observed and being offered pain relief – a legacy I hope will continue.

The supply of equipment and medicines was haphazard, and depended on what and when things were delivered. There was apparently a whole container of supplies waiting for weeks for clearance at the dock.

Many items we in Australia would discard after a single use, like surgical drains and suction, were being reused, and many of the disposables that were available were out-of-date – though they were still used without hesitation.

Some things seemed to be in oversupply, while others had simply run out.

The hospital itself needs replacing. Parts date back to World War Two. There were rats in the tea room, a cat in the theatre roof, and mosquitos in the theatre.

The hospital grounds are festooned with drying clothes, alongside discarded and broken equipment – including a load of plastic portacots, in perfect condition, but just not needed on the postnatal ward as the babies shared the bed with their mother.

It brought home how important it is to be careful in considering what equipment to donate.

The ultrasound machine and trolley we were able to donate, thanks to the John James Memorial Foundation Board, proved invaluable, as did the instruction by Dr Low in its use.

The most important question is, were we of help, and was our visit worthwhile?

I think the surgical skills we brought (such as vaginal hysterectomy), and those we were able to pass on, were extremely useful. Teaching local staff how to do a bedside ultrasound will hopefully be a long-lasting legacy. Simple things like being able to check for undiagnosed twins, dating, diagnosing intrauterine deaths, growth-restricted babies and preoperative assessments will be invaluable.

The experience was certainly outside our comfort zone, and it made me really appreciate what a great health system we have in Australia, and what high expectations we have. I want to send a big thank you to the John James Memorial Foundation for making it all possible.

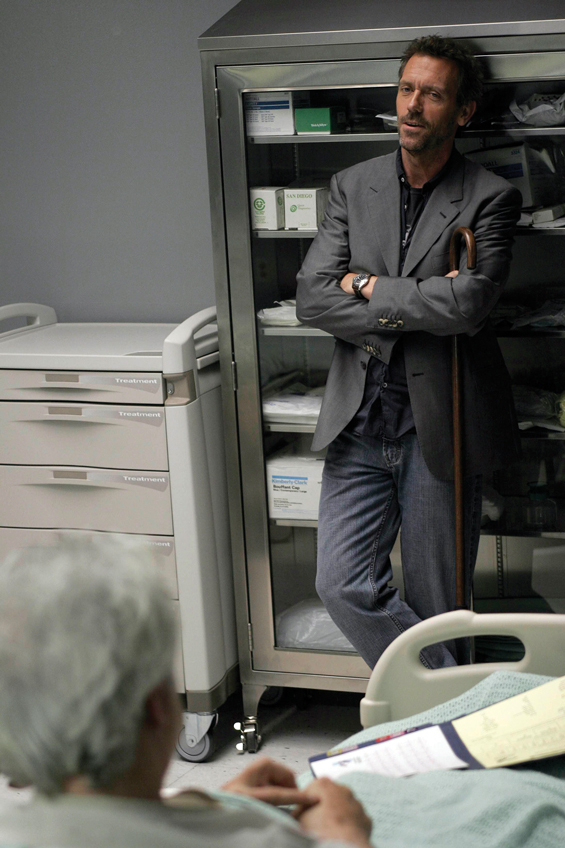

Hospital doctors’ Opinions regarding educational Utility, public Sentiment and career Effects of Medical television Dramas: the HOUSE MD study

A career in medicine has long been considered an apprenticeship, with mentors providing guidance to their trainees. The word mentor finds its origins in Greek mythology. In Homer’s Odyssey, the confidant of king Odysseus, Mentor, was trusted to guide his son and oversee his education while Odysseus fought in the Trojan War.1

The modern practice of medicine, with an emphasis on shift work, has made the classical mentor–mentee relationship more challenging,2 but the modelling of one’s practice on observed social and clinical traits of a mentor or role model remains.3 Moreover, such exposures can be factors in students’ decisions to pursue a career in medicine and even in their subsequent choice of specialty.4

The eventual choice of role model is often a personal one and may not even involve one’s own supervising senior, although it is often based on clinical experiences.5 While knowledge and clinical competence have been cornerstones of role model selection, growing evidence suggests that factors relating to personality such as compassion, good communication and enthusiasm may in fact have more influence on the expanding minds of trainees.6 Further compounding this, in some educational situations, less than half of senior clinicians were subsequently identified as being excellent role models.7

While social interactions with parents, teachers or even peers may impact on personality, outlook and practice, other media such as literature and television (TV) have been demonstrated to be significant components of this role model hypothesis.8

Medical TV programs have grown in popularity from the 1960s onwards and are now considered a staple of primetime TV.9 It has only been in more recent years that the effects of these health and illness TV narratives have been studied in greater detail.

Although their true purpose has been one of entertainment, much of their appeal is based on the perception that they are an accurate reflection of reality.10

It has been well accepted that TV can have an impact on society, increasing knowledge and influencing behaviour.11 TV medical dramas have also been shown to be of educational worth to patients12 and even doctors.13

However, they have occasionally come under criticism for unrealistic medical content, ranging from demonstration of intubation technique14 to cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).15 Frequently, in CPR situations on TV compared with actual practice, there is a higher volume of trauma cases as an underlying aetiology. Further, these scenarios often show considerably younger patients than those seen in routine CPR and survival to discharge is much better than clinically encountered.16 Concerns that this may influence the attitudes of members of the public who watch these dramas for educational purposes remain.

More recently, there has been a growing emphasis on the use of these programs as educational resources.17 In particular, some of the established role model personality traits such as ethical astuteness, communication and empathy have been sufficiently demonstrated in these series to warrant use in undergraduate teaching videos.18 Although much of the learning that can be gleaned from observing the practices of TV doctors has focused on perceived softer undergraduate educational domains,19 their use in postgraduate settings is also increasing.20

TV is a medium through which many health care workers not only take their minds off work, but also reflect both consciously and unconsciously on experiences. Students and doctors do indeed watch these programs at least as often as the general public does and, when questioned, are quite positive regarding them.21 Although not yet demonstrated, watching these series may form an early part of any role modelling or identification with certain character traits that both trainee and established medical practitioners may have.

Methods

A structured questionnaire was distributed among doctors of all grades and specialties in three large teaching hospitals in Wales, United Kingdom (Morriston Hospital, Singleton Hospital and Princess of Wales Hospital) within the Abertawe Bro Morgannwg (ABM) University Health Board, to allow capture of data from a diverse range of specialties. These were disseminated through various different locations, including departmental meetings and on-call rooms.

Questions related to respondents’ gender, specialty and grade, whether they watched medical TV dramas and their opinions regarding them, and whether they identified with characters from these programs (and if so, who) or with a non-fictional doctor encountered during their clinical careers.

Hospital grades were summarised as consultant, specialist trainee (registrar), core trainee (resident medical officer [RMO]), and foundation doctor (intern). For simplification, specialties was separated into medical, surgical, acute (eg, accident and emergency, intensive care unit, etc) and non-acute (eg, pathology, radiology, etc), although note was made of individual subspecialty answers from within these broader categories.

Statistical analysis

A cumulative odds ordinal logistic regression with proportional odds was run to determine the effect of grade and specialty on the choice and frequency of viewing of medical TV dramas. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Statistical calculations were performed using SPSS Statistics, version 21.0 (IBM).

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted by the ABM University Health Board Research and Development Joint Scientific Review Committee.

Results

Three hundred and seventy-two questionnaires were disseminated and 200 completed questionnaires were returned (response rate, 54%). Forty-six per cent of individuals completing questionnaires were women and 88% had graduated from a UK medical school. Grades and specialties of respondents are presented in Box 1.

How often do clinicians watch TV medical dramas?

One hundred and twenty-nine doctors (65%) surveyed admitted to watching TV medical dramas on more than one occasion and 14% considered themselves to be regular viewers; 15% of respondents felt that watching them as a school student positively influenced their decision to pursue a medical career.

Junior doctors were five times more likely to have watched these programs as medical students compared with more senior doctors (odds ratio [OR], 5.2; 95% CI, 2.5–10; P < 0.01). The ORs for RMOs and specialist trainees were 3.1 and 2.5, respectively, in relation to consultants (P < 0.05). Further, UK graduates were five times more likely to have watched these medical TV dramas as medical students compared with non-UK graduates (OR, 4.8; 95% CI, 2.4–9.6; P < 0.01).

The most commonly watched TV programs were Scrubs (49%), House MD (35%) and ER (21%). Most doctors who admitted to watching medical dramas did so for entertainment purposes (69%); 19% watched because there was nothing else on TV; 5% for insight into media perceptions of medical practice; and 8% for educational purposes.

Clinicians’ opinions regarding TV medical dramas

We asked individuals if they felt that TV medical dramas were educational, gave doctors a bad name, accurately showed the doctor–nurse relationship, and represented the spectrum of illnesses commonly encountered.

One hundred and three respondents (52%) felt that these shows displayed no educational value whatsoever, 52 (26%) were unsure, and 45 (23%) believed there were some educational benefits from watching them.

Evaluating the spectrum of illness represented in these dramas, 82% felt that those shown were unrealistic of daily practice. However, 20 respondents (10%) thought that they accurately portrayed reality. Most of these positive responses (16/20) were from junior doctors. No associations between the belief that medical dramas portrayed realistic life situations and specialty or frequency of viewing were observed.

Grade, specialty and country of qualification had no effect on whether a doctor believed that the programs represented current medical practice. Neither did current frequent watching or having been a regular viewer at undergraduate level.

Twenty-seven per cent of doctors surveyed felt that these programs gave doctors a bad name, although no significant differences were observed between any of the groups.

Only 13% of respondents felt that medical dramas accurately portrayed the doctor–nurse relationship, most of whom were self-admitted non-regular viewers (P = 0.01) and general practitioners or GP trainees (19/25; P = 0.05).

Outcomes of watching TV medical dramas

Thirty per cent of foundation doctors (interns) and 25% of core trainees (RMOs) felt that watching medical TV programs may have affected their career choice (to any extent) compared with more senior doctors (18%).

Compared with consultants, the OR for interns considering that watching medical TV dramas had any effect on their subsequent career choices was 4.8 (95% CI, 1.6–13.7; P = 0.013); for RMOs and specialist trainees, the ORs were 2.5 (95% CI, 1.3–5.8) and 2.7 (95% CI, 1.3–5.8) respectively; P = 0.09 and 0.13).

Specialty and country of qualification did not influence doctors’ beliefs that watching medical dramas had an effect on their career choice.

Clinicians’ identification with doctors in TV medical dramas?

A total of 121 respondents (61%) role modelled aspects of their practice on another doctor (fictional and non-fictional).

Junior doctors, particularly interns and RMOs were more likely to find commonality in their practice with fictional TV characters compared with more senior doctors (OR, 2.7; 95% CI, 1.3–5.8; P = 0.008).

Consultants were most likely not to specify any role models and, if they did so, were more likely to identify themselves with non-fictional characters (32/55) compared with other doctors, particularly interns (4/49).

Medical doctors were more likely to identify themselves with a fictional TV character (OR, 3.2; 95% CI, 1.08–9.43; P = 0.035). This was followed by 19% of acute specialty doctors and 14% of surgical specialty doctors. Non-acute specialty doctors were least likely to identify themselves with a fictional TV doctor.

The top five most popular fictional role models are shown in Box 2. Leonard McCoy (Star Trek) and Quincy (Quincy ME) were the most popular choices among consultants; the majority of positive responders were anaesthetists and pathologists. A more varied response was seen among physicians and surgeons, but note was made of a peculiar popular choice: Dr Evil (from the Austin Powers film series, Box 3) was named by four trainees, all surgical (three orthopaedic and one general surgery).

Discussion

There is a known association between clinical role models in undergraduate medicine and career choice.22 Therefore, TV medical dramas could potentially influence doctors’ and students’ opinions and have been found to be a source of entertainment for both health care professionals as well as the wider public.23

Fictional doctors have evolved into television heroes and much of their appeal is their on-screen personality as well as, in some cases, their absolute prioritisation of scientific challenge over social relationships.24 Further, much of their appeal is their ability to navigate through difficult ethical dilemmas, to make decisions that are often perceived by clinical trainees as being positive ones.25

Although clinicians watching these programs appear to do so predominantly for entertainment purposes, we found that those who watch for educational reasons show that junior trainees exposed to this genre of TV entertainment are more influenced by these series than their more senior counterparts. Interestingly, all respondents who admitted to watching TV medical dramas for educational reasons watched House MD (Box 4), perhaps suggesting that they value its learning input.

In keeping with previous studies,14–16 most doctors felt that a large proportion of what was televised may not be a true representation of clinical practice; however, suggestions that more junior trainees believe this to be so could be explained by their relative lack of clinical experiences to date.

Identifying aspects of one’s practice with witnessed exposures has been a cornerstone of the role modelling theory, but data generated from this questionnaire-based study suggest some interesting differences between specialties. Doctors who answered negatively to currently viewing or having ever viewed this type of program were least likely to admit to having been influenced into a career in medicine on the basis of TV medical dramas, thus validating the data.

It is to be assumed that consultants may look on their past seniors as role models to identify commonality of practice but the high proportion of respondents among all grades who admitted to being influenced, at least in part, by medical TV dramas suggests a much higher effect than anticipated.

Further, differences between specialities — for example, medical doctors identifying more with TV doctors compared with their surgical peers — might be explained by the sizeable volume of medically themed programs as opposed to more surgical ones. It is plausible, however, that some of the core learning traits seen in physicianly specialties, particularly regarding difficult diagnostics and ethical dilemmas, strike a chord with this group of clinicians. Specific choice of TV doctor hero as a potential role model will require further evaluation. Motivations for the popular choice of a Star Trek character among anaesthetists may include an interest in futuristic technology. Likewise, the interesting preference for Dr Evil among some surgical trainees may be due to an interest in world and/or career domination, or it may be suggestive of professional ambition rather than a display of true megalomaniac traits.

While we may be some years from continuing medical education creditation obtained from Saturday evening viewing, this study does suggest that the current generation of junior doctors relies on medical TV dramas for entertainment and education in parallel. Further observation may show some interesting effects during career progression, particularly regarding the atypical answers we received to our questions about TV doctor identification.

Box 1 –

Grade and specialty of respondents (n = 200)

|

Grade and specialty |

No. (%) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Grade |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Intern |

49 (24.5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Core trainee (RMO) |

60 (30.0%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Registrar (specialist trainee) |

36 (18.0%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Consultant |

55 (27.5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Specialty |

|

||||||||||||||

|

Medical |

83 (41.5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Surgical |

36 (18.0%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Acute non-medical |

27 (13.5%) |

||||||||||||||

|

Non-acute |

20 (10.0%) |

||||||||||||||

|

GP or GP trainee |

34 (17.0%) |

||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

RMO = resident medical officer. |

|||||||||||||||

Box 2 –

Most popular fictional television doctor role models

|

Rank |

Doctor |

Show |

Most popular among: |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

1 |

Elliot Reid |

Scrubs |

Women, junior trainees |

||||||||||||

|

2 |

Perry Cox |

Scrubs |

Specialist trainees, physicians |

||||||||||||

|

3 |

Leonard McCoy |

Star Trek |

Consultants, anaesthetists |

||||||||||||

|

4 |

John Carter |

ER |

Physicians, acute specialties |

||||||||||||

|

5 |

R Quincy |

Quincy ME |

Consultants, non-acute specialties (pathologists) |

||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

Building on the rich heritage of the Medical Journal of Australia

My professional interests span clinical practice, medical education and research, medical leadership, health policy and social justice. My goals as editor are to build on the outstanding DNA of the Journal, further increasing its relevance and readability, and attracting the highest quality submissions. We will aim to build on the Journal’s rich heritage by continuing our practice of publishing the best clinical science papers that have the potential to transform practice, including clinical trials and comparative effectiveness research. We will also aim to inform readers on advances in medical education, and cover issues from medical leadership to re-engineering our health system. We will continue to seek expert reviews, editorials and commentaries, meta-analyses and guidelines, and the latest news and information that everyone in practice needs to know. It is my goal to reinforce the unique role that the Journal plays as the pre-eminent publisher of Australian medical research and as a vital platform for translating research into practice, as well as helping to inform the broader health policy debate. This is part of the Journal’s success and why it is relevant to clinicians, researchers and academics across the nation.

The MJA is prestigious and influential, but another advantage to publishing with us is that much of the content including our research content is published freely on our website at mja.com.au, without the waiting period often imposed by other journals. I can also assure readers that as Editor-in-Chief, I have a guarantee of editorial independence and I will fiercely guard this independence on your behalf. For the nearly 32 000 subscribers who receive the MJA in print, and the many others who read the Journal online, the team will work tirelessly to provide the best medical journal experience possible.

We live in a world that, in terms of connectivity through social media, is rapidly shrinking, and the MJA has an important role to play not just nationally but globally. We will therefore now be encouraging locally relevant international articles. And we will continue to tackle in our pages articles that highlight the tough health issues we all face and provide possible solutions, from the health needs of Indigenous Australians to the health impacts of global migration, population growth, dwindling resources, an ageing population and climate change, to name a few. We will look both out to the world and across Australia to find the objective data that can help guide us all. We will seek balance among the many expert opinions and will aim at all times to be rigorous, evidence-based and transparent.

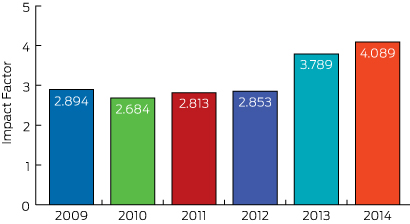

Whether any of us like it or not, our performance in medicine is being increasingly measured and critiqued, and it’s no different for medical journals. Clinicians and academics want to publish in the best medical journals and one metric applied universally is the impact factor, calculated by counting the mean number of citations received per article published during the previous 2 years. In the best journals, editors arguably “live and die” by the journal impact factor published each year. The impact factor is flawed (some argue fatally so) and is not used by the National Health and Medical Research Council; but it can’t be ignored either!1,2 In 2015, the MJA, your national journal, ranks in the top 20 general medical journals worldwide and has a highly respectable impact factor of 4.089 (Box, previous page). I am pleased to say that the impact factor of the MJA has risen and I anticipate over the coming years that it will continue to rise (as will other metrics of excellence) as we further increase the quality and reach of what we publish.

We welcome your best work being submitted for consideration. Our acceptance rate is currently falling (as marks all of the best medical journals) but I can pledge that your medical articles will be expertly peer reviewed and edited before publication. The editorial team will do its utmost to ensure it makes the best possible decisions, and we will work hard with authors to help them publish polished, excellent contributions.

Finally I would like to acknowledge and thank Professor Charles Guest in his capacity as Interim Editor-in-Chief for his stewardship of the Journal in the second half of 2015. He has been instrumental in supporting our editors and maintaining the continuity and the quality of the Journal.

Thank you for reading the MJA. You can expect that the Journal will be further increasing its scientific reputation and international presence over the next few years, and I hope you will be part of it if you have a contribution you wish to make. We welcome suggestions and feedback so we can further improve the Journal on your behalf. I am committed to strengthening your clinical practice through its pages and look forward to our journey together.

‘Flashpoint’ warning as Medibank pushes cost agenda

The nation’s largest health insurer will no longer cover the costs of many patients who become sick or injured in hospital as a result of what it deems to be avoidable medical complications or errors under the terms of a deal struck with major private hospital operator Healthscope.

In an important development for Medibank Private as it tries to squeeze down on payouts, the insurer and Healthscope have reached agreement on a two-year contract that includes provisions regarding the safety and quality of care.

While the details of the arrangement have not been publicly disclosed, it is believed to include clauses regarding liability for costs arising from hospital acquired complications and avoidable readmissions.

The deal follows an attempt by Medibank earlier this year to pressure Calvary Health Group into accepting responsibility for 165 complications the insurer described as preventable, including deep vein thrombosis and maternal death arising from amniotic fluid embolism.

The demand initially led to a breakdown in negotiations, but eventually Medibank and Calvary reached agreement – though the terms remain confidential.

A senior hospital executive has warned the issue could become a “flashpoint” for the sector.

“To use quality and safety to some extent as a Trojan horse, and taking the role of arbiter of quality and safety for the contributor is interesting,” Calvary Chief Executive Mark Doran told a UBS Australasia conference in Sydney in November. “It means you’re in conflict with the medical profession, who see themselves as the arbiter of quality and safety for their patient. If you don’t engage with them, you risk them pulling back.”

Medibank’s deal with Healthscope is significant for the insurer because the company operates 46 private hospitals across the country and provides around 165,000 episodes of care to Medibank members each year.

Healthscope Chief Executive Officer Robert Cooke insisted his company was “working in partnership” with Medibank in reducing waste and inefficiency.

“Healthscope has a longstanding commitment to improving our patients’ experience in hospital, including robust safety and quality programs,” Mr Cooke said. “Medibank’s focus on reducing hospital acquired complications and avoidable readmissions is complementary to the quality data we have been publishing since 2012.”

Outgoing Medibank Managing Director George Savvides said the Healthscope deal was one of a number of “performance-based contracts” it was seeking to strike with hospital providers, and set an example of how insurers and providers could work together to “maintain excellence…while also reducing rising health costs”.

But AMA President Professor Brian Owler said “close attention” needed to be paid to what Medibank was trying to do.

Professor Owler said that because hospital expenses and prosthetics together made up about 85 per cent of private health fund costs, it “stands to reason” these would be a focus for Medibank.

The major health funds have commissioned a report on prosthetic costs amid complaints they are paying $800 million a year more on devices compared with the public sector.

But Professor Owler warned that the insurer should not pursue cost-cutting under the guise of patient safety and quality assurance.

“What we don’t want is punitive measures that punish patients and interfere in what would otherwise be routine clinical cases in order to save money,” the AMA President said.

While some serious mistakes, such as operating on the wrong limb or transfusing the wrong blood type, should never occur, Professor Owler said complications were an unfortunate but inevitable part of clinical practice, particularly when doing high-risk procedures on patients with multiple co-morbidities.

“Of course, every effort should be made to minimise these complications, but we are never going to be able to eliminate them,” he said.

Professor Owler said if Medibank’s true goal was to increase patient safety and improve quality, imposing financial penalties was the wrong way to go about it.

He said there was already a multilayered system in place to improve quality of care, including clinical groups, peer reviews, continuous professional education and training and accreditation standards.

“Financial penalties should not be the major lever to try and improve the quality of care,” Professor Owler said. “Doctors and nurses are already very motivated to improve the outcomes of care for their patients.”

Adrian Rollins

more_vert

more_vert