Inspection of the jugular veins provides a simple means of determining whether pressures in the right side of the heart are normal or elevated. With practice, clinicians can derive accurate and reliable information relevant to diagnosis and patient care.

Identifying a venous pulsation

It is not necessary to position the patient at precisely 45 degrees.1,2 If your patient is in a chair, examine them in that position. If they are on a couch or bed, examine them in the position that you find them.

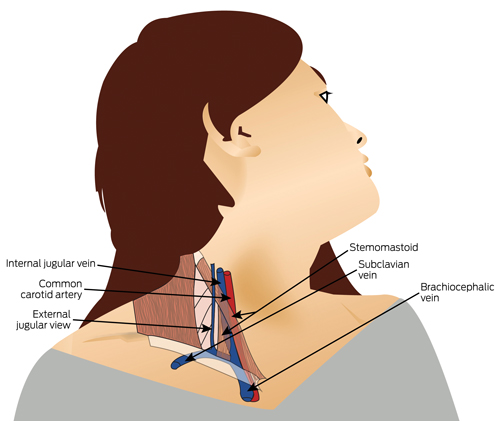

Explain to the patient why you want to look at their neck. Traditionally, the right side of the neck has been used for jugular vein examination. However, it is often more difficult to see pulsations on the same side as you are positioned and, importantly, it is known that measurements made from the left side of the neck have similar accuracy.3 Further, inspection of the external, rather than internal jugular vein are also of similar accuracy.4 If you do use the ipsilateral side of the neck, try side-lighting with a torch or looking tangentially across the skin, rather than directly at it. Whichever side you use, and whichever vein, there must be visible pulsation at the top of the venous column. If there is no visible pulsation, do not use that vein as a manometer.

Ask the patient to turn their head slightly away from the side you are observing and focus on the area where the internal jugular vein is located — the anterior triangle (Box 1).

If you cannot see any pulsation at all, try lying the patient flatter or sitting them up — this may make a venous pulsation visible. If you still cannot see any pulsation, try sustained firm pressure in the upper abdomen. This is known as abdominojugular reflux and may transiently elevate a venous pulsation from below the clavicle and make it visible. If you have to do this to make a venous pulsation visible, it usually means that the right atrial pressure is not elevated.

When you identify a pulsation, decide whether it is arterial or venous. Box 2 shows the key distinguishing features.

If you decide that the pulsation is arterial, try abdominojugular reflux or changing the position of the patient to see if any additional pulsation appears.

If the veins of the neck seem distended but are non-pulsatile, sit the patient up at 90 degrees. This may make the pulsatile top of a venous column visible.

On most occasions, unless the patient is very obese, this systematic approach will allow confident identification of a venous pulsation. You can then use the pulsation to estimate right atrial pressure, whatever position the patient is in.

Estimating the right atrial pressure from observation of a jugular vein pulsation

When you identify a jugular vein pulsation, do not try and make a measurement in centimetres, just decide whether the pressure is normal or elevated. The simplest way to do this is as follows. If the top of the pulsating venous column can be seen to be more than 3 cm above the angle of Louis (sternal angle) in whichever way you have positioned the patient, this is highly predictive of an elevated right atrial pressure.1 Remember that clinical evaluation of the jugular vein pressure, just like ultrasound evaluation, typically underestimates the right atrial pressure.1 If you are confident that the jugular vein pressure is elevated, this reinforces the likelihood that the right atrial pressure is high.

What do I need to know about the waveform?

The jugular vein waveform is complex with three peaks — atrial contraction (a), ventricular contraction (c) and venous filling of the atrium (v) — and two troughs — atrial relaxation (x) and ventricular filling (y). Most clinicians can recognise the multiphasic quality of the venous pulsation but cannot confidently identify the specific peaks and troughs or their abnormalities. In real life clinical practice, this is of little importance. However, one abnormality of waveform is not uncommon. The video at www.mja.com.au demonstrates the giant v wave, which makes the venous pulsation almost look uniphasic and can mimic arterial pulsation if the steps described in Box 2 are not followed. This waveform is highly predictive of the presence of tricuspid regurgitation.5

Clinical value of jugular vein pressure estimation

In situations when accurate and multiple measurements of right atrial pressure are required — for example, the acutely unwell patient in a high dependency or intensive care setting — direct measurement by invasive (catheter) or non-invasive (ultrasound) means is usually preferred.

However, for the large numbers of patients cared for in ambulatory or general ward settings — particularly when heart failure is questioned as a diagnosis, or is known to be present and decisions about treatment are required — evaluation of the venous pressure by the method described here remains valuable. In the longer term, bedside ultrasound may supersede this technique. However, in the immediate future and in the absence of widespread access to such technology, bedside assessment of jugular venous pulsation is accurate and convenient, and continues to be a gateway to good clinical care of patients with heart disease.

Box 2 –

Features that help distinguish an arterial from a venous pulsation in the neck

|

|

Arterial pulsation |

Venous pulsation |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

Appearance |

Uniphasic, single |

Multiphasic, undulating, flickering* |

|||||||||||||

|

Effect of changing the position of the patient |

None |

May change its position in the neck |

|||||||||||||

|

Effect of respiration |

None |

Falls on inspiration, rises with expiration |

|||||||||||||

|

Palpation over the pulsation |

Palpable |

Impalpable (but beware of pressing too deeply, as you may feel the carotid) |

|||||||||||||

|

Effect of gentle pressure at base of neck |

None |

Ceases |

|||||||||||||

|

Effect of sustained pressure on the upper abdomen (abdominojugular reflux) |

None |

Transient rise |

|||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||

|

* The video at www.mja.com.au shows an exception to this general rule. |

|||||||||||||||

more_vert

more_vert