Dr Govinda KC, a senior orthopaedic surgeon and a professor at Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital, is staging a series of hunger strikes to reform medical education and the health system in Nepal. At every attempt, the government has promised to fulfil his demands, yet never gone through with its promises, and the media report that the unwillingness of government has generated his eight hunger strikes.1,2

Preference: Education

190

[Correspondence] England’s teenage pregnancy strategy has been a success: now let’s work on the rest

England’s Department of Health and all those who contributed to the Teenage Pregnancy Strategy must be congratulated for their efforts in reducing teenage conceptions through a “sustained, multifaceted policy intervention involving health and education agencies”.1 The strategy is even being considered for implementation in low-income and medium-income countries that also seek to address high teenage pregnancy rates.2

[Review] Doctors in China: improving quality through modernisation of residency education

There is growing recognition that the ultimate success of China’s ambitious health reform (enacted in 2009) and higher education reform (1998) depends on well educated health professionals who have the clinical, ethical, and human competencies necessary for the provision of quality services. In this Review, we describe and analyse graduate education of doctors in China by discussing the country’s health workforce and their clinical residency education. China has launched a new system called the 5 + 3 (5 year undergraduate and 3 year residency [standardised residency training]), which aims to set national quality standards.

Health costs rise as rebate freeze bites

Patients face higher out-of-pocket costs as the medical profession struggles under pressure from the Federal Government’s Medicare rebate freeze.

As a result of the Government’s freeze, the gap between the Medicare rebate and the fee the AMA recommends GPs charge for a standard consultation will increase to $40.95 from 1 November, up from $38.95, continuing the steady devaluation of Medicare’s contribution to the cost of care.

The increase comes on top of the effects of the Medicare rebate freeze, which is forcing an increasing number of medical practices to abandon or reduce bulk billing and begin charging patients in order to remain financially viable.

Adding to the financial squeeze, the Government is considering changes that would cut the rents practices receive for co-located pathology collection centres that the AMA estimates would rip up to $150 million from general practice every year.

Under the changes recommended by the AMA, the fee for a standard Level B GP consultation will increase by $2 to $78, while the Medicare rebate remains fixed at just $37.05.

AMA Vice President Dr Tony Bartone said doctors had kept medical fee increases to a minimum, but Medicare indexation lagged well behind the cost of providing medical care.

“The MBS simply has not kept pace with the complexity or cost of providing high quality medical services,” Dr Bartone said.

The rise is roughly in line with Reserve Bank of Australia forecasts for underlying inflation, currently at 1.5 per cent, to rise anywhere up to 2.5 per cent by the middle of next year, and reflects steady increases in medical practice costs.

Staff wages, rent and utility charges have all increased, as have professional indemnity insurance premiums, continuing professional education costs and accreditation fees.

While practice running costs are rising, the Government’s contribution to the cost of care through Medicare has been frozen for more than two years, and in many cases far longer.

The Medicare rebate for GP services has not been indexed since mid-2014, while the last rebate increase for most other services was in November 2012. In the case of pathology and diagnostic imaging the rebate freeze is even longer, going back more than 15 years.

Dr Bartone said the rebate freeze was pushing up patient out-of-pocket costs.

“Many patients will pay more to see their doctor because of the Medicare freeze,” he said. “The freeze is an enormous burden on hardworking GPs. Practices cannot continue absorbing the increasing costs of providing quality care year after year. It is inevitable that many GPs will need to review their decision to bulk bill some of their patients.”

The AMA is pressing the Government to reverse the rebate freeze, and AMA President Dr Michael Gannon has declared he would be “gobsmacked” if it was still in place by the time of the next Federal election, due in 2019.

But Health Minister Sussan Ley has played down hopes that indexation will soon be reinstated, warning that there will not be a change of policy “any earlier than our financial circumstances permit”.

The Government is trying to curb the Budget deficit and rein in ballooning debt.

As part of its strategy, it is increasingly pushing the cost of health care directly onto patients.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare figures show the Commonwealth’s share of the nation’s health bill slipped down to 41 per cent in 2014-15, while patients’ share has increased to almost 18 per cent, and Australians now pay some of the highest out-of-pocket costs for health care among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries.

The cost of health

How AMA recommended fees compare with the frozen Medicare rebates

|

Medical Service |

AMA Fee (2015) |

AMA Fee (2016) |

MBS Schedule Fee (2016) |

|

Level B GP consult (MBS item 23) |

$76.00 |

$78.00 |

$37.05 |

|

Level B OMP consult (MBS item 53) |

$76.00 |

$78.00 |

$21.00 |

|

Blood test for diabetes (MBS item 66542) |

$48.00 |

$49.00 |

$18.95 |

|

CT scan of the spine (MBS item 56219) |

$990.00 |

$1,055.00 |

$326.20 |

|

Specialist – initial attendance (MBS item 104) |

$166.00 |

$170.00 |

$85.55 |

|

Consultant Physician – initial attendance (MBS item 110) |

$315.00 |

$325.00 |

$150.90 |

|

Psychiatrist attendance (MBS item 306) |

$350.00 |

$355.00 |

$183.65 |

Adrian Rollins

[Comment] Offline: The quant revolution and why it matters

“We have beaten development.” What did Chris Murray mean? How can one beat development? He was speaking to an overflowing hall at George Washington University during the launch last week of the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study 2015. I think he meant that observed health outcomes in some countries have outpaced expected outcomes—expected, that is, based on measures of a nation’s wealth, education, and fertility. Some nations have found a strange kinship. The USA and Russia, for example, are both performing worse than one would have expected in their quest to achieve the health-related Sustainable Development Goals.

[Articles] Measuring the health-related Sustainable Development Goals in 188 countries: a baseline analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015

GBD provides an independent, comparable avenue for monitoring progress towards the health-related SDGs. Our analysis not only highlights the importance of income, education, and fertility as drivers of health improvement but also emphasises that investments in these areas alone will not be sufficient. Although considerable progress on the health-related MDG indicators has been made, these gains will need to be sustained and, in many cases, accelerated to achieve the ambitious SDG targets. The minimal improvement in or worsening of health-related indicators beyond the MDGs highlight the need for additional resources to effectively address the expanded scope of the health-related SDGs.

[Articles] Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015

Health is improving globally, but this means more populations are spending more time with functional health loss, an absolute expansion of morbidity. The proportion of life spent in ill health decreases somewhat with increasing SDI, a relative compression of morbidity, which supports continued efforts to elevate personal income, improve education, and limit fertility. Our analysis of DALYs and HALE and their relationship to SDI represents a robust framework on which to benchmark geography-specific health performance and SDG progress.

A medical student’s first experience of theatre

Disrupting the neat choreography and finding my part in it

After weeks of trawling through abstracts and entering data into Excel spreadsheets for a summer research project, my supervisor asked whether I would like to go into theatre to watch a thyroidectomy. Of course, my heart leapt at the thought. As a first year student, I had never been into theatre so I had no idea of what to expect. I wondered whether watching all of Grey’s anatomy would help and whether my anatomy knowledge would be up to scratch.

I was told to arrive at 6 am outside the change rooms, much too early for me to fit in breakfast. The consultant told me to meet him on the other side and, in my hurry to not hold him up, I put my scrubs on backwards and left my name tag in my bag. At last, I came out the other side feeling confident and ready for action. The start of the surgery was like a ballet, from the elegant pirouette of the surgeon as he spun around to put on his gown to the blinding theatre lights and the exact positioning of everyone in the room — not a centimetre out of place. I had an awful sense that I was disrupting this neat choreography.

The consultant ushered me closer and told me to place my hands on the patient. Next, he told me to switch positions with the registrar so that I could hold a retractor. I stood like a statue, petrified that I might do something wrong or get in the way. I became fixated on the carotid artery, red and pulsating. I felt terrible. I had never fainted before but I felt as though I was going to. I became acutely aware of the beeping of the monitors and the smell of burning flesh. I looked at the scrub nurse but could not articulate what was going on. She seemed to know and calmly grabbed the instrument off me, while I inched slowly backwards towards the wall. I did not actually lose consciousness but the anaesthetist told me to go and have something to eat. Why did I not have breakfast?

The anaesthetist found me in the kitchen. I was so embarrassed about what had happened. He reassured me that at least once a month a new student faints and that, in fact, I had done an excellent job of recognising the signs and walking away from the table so as not to cause any distraction. He told me I had a decision to make. I could go home or I could come back for the next operation. I decided I should to do just that and followed him back inside. I successfully watched three more thyroidectomies without any problem. I was also pleased to learn that the surgeon did not even know that I had left the room.

Early emotional experiences in the theatre can have a detrimental impact on students’ learning and future career choices. Interviews of medical students carried out by Bowrey and Kidd1 suggested that negative feelings surrounding the theatre were common and included concerns about violating theatre protocol as well as a fear of syncope. Jamjoon and colleagues2 reported that 12% of penultimate and final year students experienced near or actual syncope in the theatre and 9% reported being discouraged from pursuing a surgical career by a syncopal episode. The study found that the most useful measures that students could employ to avoid syncope were eating before the surgery and leg movements when standing for prolonged periods.

It is common for medical students to feel anxious about new clinical experiences and their first time in theatre is no exception. In an attempt to foster a positive learning experience, some Australian universities have introduced “surgical skills” as part of their first or second year programs. In these sessions, students learn to scrub in an environment where they feel comfortable and supported. They may also participate in mock theatre demonstrations and explore the role of each member of the surgical team. Students who feel knowledgeable about sterility, surgical attire and the surgical environment before they enter theatre will be more confident and able to focus on their learning. Before the surgery, students can prepare by revising the patient’s condition as well as the planned surgical procedure.3

Orientation days at teaching hospitals could provide students with the chance to familiarise themselves with the operating theatre environment before they attend a surgery. Staff can help remove the stigma around syncope by directly raising the issue and suggesting preventive measures. It helps if they are approachable and encouraging and make students feel socially included within the theatre team.2 These strategies may ensure that students are well prepared and have a positive learning experience.

In theatre, students will learn more about anatomy than they ever could from a cadaver or a textbook. They are able to put their theoretical knowledge into practice and observe the treatment of a condition from start to finish. They begin to appreciate the unique relationship of trust between the patient and doctor and the importance of working well within a team. In teaching students, supervisors should reflect on their own early clinical years and be mindful of their ability to inspire a love of surgery in the next generation of doctors.

On a personal note, I have realised that there is no need to be embarrassed about what happened during my first experience of theatre and that I can learn much from it to inform my clinical years. However, it was certainly an experience that I will not forget.

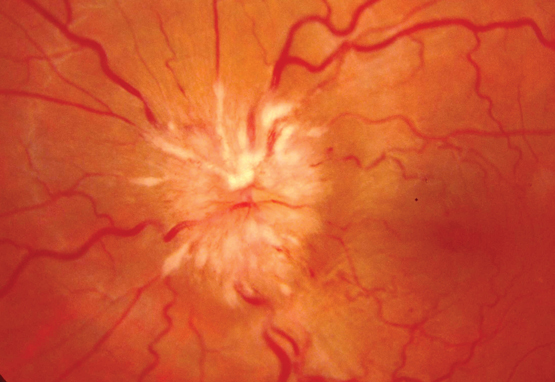

Central retinal venous pulsations

Diagnosing raised intracranial pressure through ophthalmoscopic examination

The ophthalmoscope is one of the most useful and underutilised tools and it rewards the practitioner with a wealth of clinical information. Through illumination and a number of lenses for magnification, the direct ophthalmoscope allows the physician to visualise the interior of the eye. Ophthalmoscopic examination is an essential component of the evaluation of patients with a range of medical conditions, including diabetes mellitus, systemic hypertension and conditions associated with raised intracranial pressure (ICP). The fundus has exceptional clinical significance because it is the only location where blood vessels can be directly observed as part of a physical examination.

Optic disc swelling and central retinal venous pulsations are useful signs in cases where raised ICP is suspected. Both signs can be obtained rapidly by clinicians who know how to recognise them. Although optic disc swelling supports the diagnosis of raised ICP, the presence of central retinal venous pulsations may indicate the contrary.

In the standard technique for direct ophthalmoscopy, the patient is positioned in a seated posture and asked to fix their gaze on a stationary point directly ahead. Pupillary dilation, removal of the patient’s spectacles and dim room illumination usually aid the examination. To start examining the patient, set the ophthalmoscope dioptres to zero — alternatively, a suitable setting would be the sum of the refractive errors of the patient and the examiner. Use the right eye to examine the patient’s right eye and vice versa. Using a slight temporal approach facilitates the identification of the optic disc, which also minimises awkward direct facial contact with the patient. Examine the red reflex at just under arm’s length. A pale or absent red reflex may suggest media opacity, such as a cataract. Next, on approaching the patient and obtaining a clear view of a retinal vessel, follow its course toward the optic disc. The presence or absence of venous pulsations should be appreciable (see the video at www.mja.com.au; pulsations of the central vein are clearly visible at the inferior margin of the optic disc). These pulsations, usually of the proximal portion of the central retinal vein, are most readily identified at the optic disc. The examination of the fundus should be concluded by visualisation of the four quadrants of the retina and examination of the macula.

Central retinal venous pulsations are traditionally attributed to fluctuations in intraocular pressure with systole, although this is may be an incomplete explanation.1 Patients with central retinal venous pulsations generally have cerebrospinal fluid pressures below 190 mmHg.2 Based on the results of Wong and White,3 the positive predictive value for retinal venous pulsations predicting normal ICP was 0.88 (0.87–0.9) and the negative predictive value was 0.17 (0.05–0.4).

This is important when considering lumbar puncture and when neuroimaging is not available. A limitation of this sign is that about 10% of the normal population4 do not have central retinal venous pulsations visible on direct ophthalmoscopy.4 The absence of central retinal venous pulsations does not, by itself, represent evidence of raised ICP; some patients with elevated ICP may still have visible retinal venous pulsations.

Papilloedema (optic disc swelling caused by increased ICP) may develop after the loss of retinal venous pulsations. This change in the appearance of the optic disc and its surrounding structures may be due to the transfer of elevated intracranial pressure to the optic nerve sheath. This interferes with normal axonal function causing oedema and leakage of fluid into the surrounding tissues. Progressive changes include the presence of splinter haemorrhages at the optic disc, elevation of the disc with loss of cupping, blurring of the disc margins, and haemorrhage. In later stages, there is progressive pallor of the disc due to axonal loss. A staging scale, such as that of Frisén,5 can be used to reliably identify the extent of papilloedema (Box).

Diabetes management — keeping up to date

The management of type 2 diabetes (T2D) is rapidly evolving with the introduction of an increasing number of new medicines, updating of guidelines and emerging clinical outcome data. Medicine selection for treatment of T2D has become increasingly complex — especially when considering the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme subsidy of certain medicine combinations. On the other hand, some things have not changed; optimising glycaemic control, managing risk of complications and promoting a healthy lifestyle are still the cornerstones of diabetes care. Despite the new medicines available for the treatment of T2D, prescribers should continue to individualise their choice of therapy at each point of escalation based on patient and medicine factors.

Beyond selecting the most appropriate therapy lies the challenge of improving adherence to diabetes medicines. Better adherence to medicines ensures that patients achieve their glycaemic targets and reduce the risk of short and long term diabetes complications. It is important to assess adherence before intensifying diabetes therapy, which may help identify adverse events.

An emerging change, opportunity and challenge for prescribers will be the use of biosimilars in diabetes management, beginning with insulin analogues. Biological agents come with their own set of efficacy and safety considerations, which may influence prescribing in primary care settings. The diabetes environment is soon to be affected by these considerations by way of the new insulin glargine biosimilar.

By being better informed about medicine choices, health professionals can help people with T2D to achieve improved glycaemic control, reduce associated long term complications and minimise medicine-related adverse effects. The new educational program from NPS MedicineWise — “Type 2 diabetes: what’s next after metformin?” — provides general practitioners, pharmacists, practice nurses and diabetes educators with the latest evidence on second and third line medicines for lowering blood glucose levels and with strategies for improving adherence to metformin therapy. To access the educational program, visit www.nps.org.au/diabetes.

more_vert

more_vert