The shoulder joint could be described as a trade-off between range and stability. The striking range of movement of this joint is achieved by its shallow articulation and a dynamic cuff of the shoulder muscles and their associated tendons. It is therefore not surprising that ageing has more impact on the soft tissues of the shoulder than on other more stable and less dynamic joints.

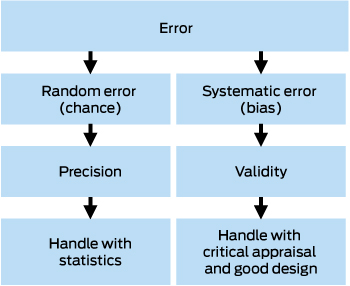

An Australian population study1 showed the importance of the history and examination of the shoulder, rather than imaging. In this study, multiple asymptomatic changes in the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan were observed in healthy individuals, and there was a poor correlation between shoulder pain and change in the MRI scan. In many cases, the clinical examination features are mainly diagnostic. Worldwide, there is a well defined, age-dependent increase in the frequency of rotator cuff tears in asymptomatic shoulders.2 In keeping with many joint examination techniques, a series of steps (including look, feel, move and special tests) remains valid with the shoulder.

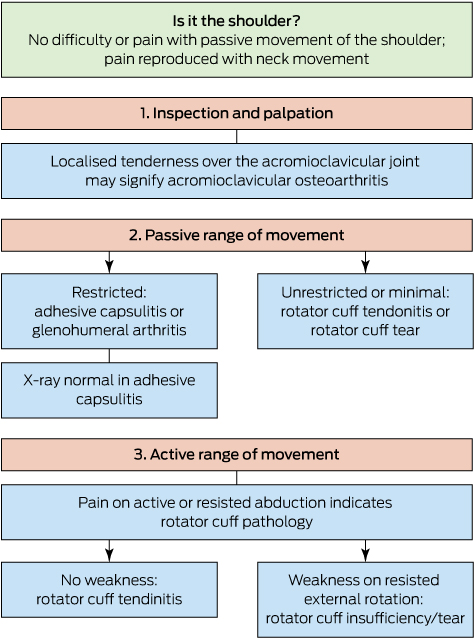

Physical examination is not a blind or formulaic activity. We need to examine the patient in a sequence to answer specific questions based on diagnoses that may become more or less likely as the examination proceeds (Box 1). The first question should be: is the pain really emanating from the shoulder? If the shoulder is non-tender and moves easily, it is likely that the pain is coming from the neck or other structures, and proceeding with the shoulder examination is unlikely to yield a diagnosis.

If the shoulder joint is established as the source of pain, there are four main shoulder conditions to consider as the examination proceeds:

-

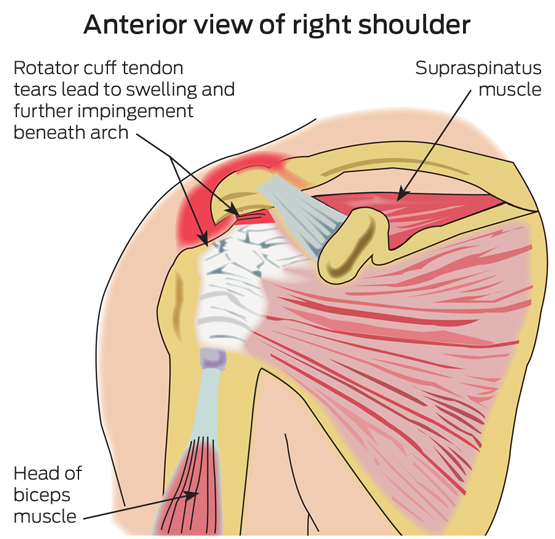

rotator cuff tendinitis and impingement (Box 2);

-

rotator cuff tear, in the case of older patients (Box 2);

-

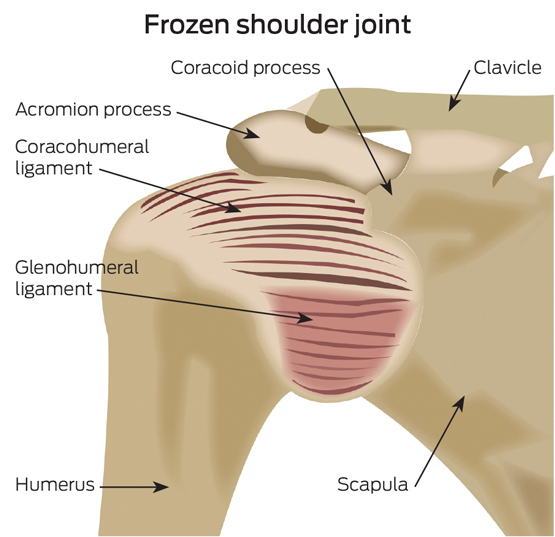

frozen shoulder, that is, adhesive capsulitis (Box 3); and

-

arthritis of the glenohumeral joint.

In practice, we can consider shoulder problems to be divided into two main groups, based on whether there is restriction of passive shoulder movement.3 Restricted range of passive movement suggests either adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) or arthritis of the glenohumeral joint. Absence of restriction of passive movement points to impingement syndrome (rotator cuff tendinitis) or a rotator cuff tear. After inspection and palpation, the key step is to examine the shoulder and take it passively through its range of movement.

Passive range of shoulder movement

A relatively unrestricted range of passive movement in all directions suggests that the problem is not emanating from the shoulder, and that it may be referred from the neck or other structures, or that it falls into the category of one of the rotator cuff problems, which include rotator cuff tendinitis, tendonopathy and subacromial bursitis.

If there is a global restriction of passive movement (ie, partial or full restriction in all directions), it may suggest arthritis of the shoulder or frozen shoulder. It is increasingly appreciated that the classic description of a frozen shoulder, in which there is a profound global restriction of movement, does not encompass all cases. For example, much milder global restriction of the shoulder — with a loss of 20–30° of movement in all directions — may be seen in some cases of frozen shoulder.

For these two conditions, which cause restriction of shoulder motion, an x-ray is required to discriminate between frozen shoulder and arthritis of the glenohumeral joint. This may resolve the problem with much greater reliability than any other examination.

Conditions not associated with significant restriction of passive movement include rotator cuff tendinitis or impingement and rotator cuff tear. There are two clues to differentiating between significant rotator cuff tear and tendinitis and impingement syndrome. The first is the age of the patient. Impingement syndrome and rotator cuff tendinitis are more commonly seen in people under the age of 40–50 years. In the population over 50 years, and with increasing frequency with each decade of age after 50 years, the underlying pathology usually involves degenerative change in the tendons of the rotator cuff, particularly supraspinatus, with frank tears.

Active range of shoulder movement and power testing

In a patient with preserved passive range of movement, pain on active and resisted abduction supports the idea of rotator cuff pathology. If there is weakness, particularly in resisted external rotation, this supports a diagnosis of rotator cuff tear.

An examination of power at the shoulder is, therefore, a major discriminator that indicates the presence of a rotator cuff tear of significance. If the rotator cuff is intact, even if inflamed, there will be good preservation of power.

It should be noted that pain on active horizontal adduction of the shoulder (across the body) can also be seen with osteoarthritis at the acromioclavicular joint.

more_vert

more_vert