The known Universities, medical authorities and employers are interested in whether medical graduates are adequately prepared for practice. Medical graduates’ self-assessment of their capabilities on entering the workforce are relevant to this question.

The new Graduates from the Launceston Clinical School generally felt well prepared for the transition to clinical practice as a junior doctor.

The implications Reforms of undergraduate medical education should focus on moving graduates from feeling merely prepared to being well or extremely well prepared by the time they commence practice. The survey could be administered more broadly to obtain a national, longitudinal perspective of perceived preparedness.

The dual responsibility of medical schools — to train doctors in the capabilities they need for practice immediately after graduating, and to prepare them for adapting to constantly changing health employment systems — is being examined in the context of an increasing focus by governments and higher education bodies on how prepared graduates are for medical practice.1–4 Most medical graduates in Australia are employed as doctors, but it is important to determine whether all are prepared to fulfil their duty of care in the face of the challenges posed by the increasing complexity of health care practice and systems.5 Higher education leaders seek to produce graduates who are “work ready plus”; that is, possessing capabilities that are relevant for future workplace requirements, not just current needs.6

Employability skills in the medical profession are high order capabilities: knowledge and skills, the capacity to continue to learn, the ability to perform in changing contexts and to be clear in professional purpose.2,7,8 In his recent report on transforming graduate capabilities, Geoffrey Scott discussed the “work ready plus” capabilities required by university graduates for future employability, including being able to implement change, to work in partnership, and to manage the unexpected, as well as being clear about their role in driving change.6

Concern has been expressed about how prepared graduating doctors are for delivering patient-centred care, about the erosion of patient-centredness during basic medical training, and about their capacity to provide this care as health care workers.9,10 The final report of the Review of Medical Intern Training commissioned by the Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council noted a “lack of objective, accessible and current data … on the level of graduate preparedness”.9

As the evidence for improved health outcomes and cost-effectiveness associated with patient-centred care mounts,11,12 understanding and teaching patient-centred care is becoming pivotal for cultivating graduates with a refined professional identity; that is, with patient-centredness embedded in their sense of who they are as a doctor, in their attitude and approach to medicine, so that they are more able to champion this approach in the health care system. The synergy achieved by aligning Scott’s “work ready plus” requirements6 with patient-centred medicine will enable doctors to work in partnership with patients, to cope with uncertainty, and to develop a well formed, patient-centred professional identity for managing the complex chronic health problems affecting patients and the community.

The regional Launceston Clinical School (LCS), one of three clinical schools at the University of Tasmania, has provided about 40 students from each of the final two years of a 5-year undergraduate degree with a specific patient-centred learning program,13 alongside traditional clinical hospital rotations and case-based learning, since 2005. In the executive summary of the NSW Health Education and Training Institute Medical Portfolio Programs report, emphasis was placed on the fact that the “characteristics of future doctors and the content of the curriculum and ways of teaching and learning must reflect the need for a greater focus on professionalism and the quality and safety of patient care.”8

As a pilot study in an Australian setting, we surveyed medical graduates about their perceptions of how well their undergraduate education at the LCS prepared them for a range of practice capabilities, including those central to patient-centred care.

Methods

Study design

Graduates’ perceptions of their preparedness for practice were surveyed with a self-report instrument, administered with the cloud-based SurveyMonkey software.

Participants and sample

All contactable medical graduates who attended the LCS during 2005–2014 were invited by email to participate. Alumni records and social media, among other sources, were used to identify current email addresses. Reminder emails were twice sent to non-responders.

Survey

A survey previously developed by the Peninsula Medical School (Plymouth University, United Kingdom)3 was, with permission, modified for this study. The curricular emphasis at the Peninsula School on working with patients in activity learning contexts is comparable with the LCS patient partnership learning encounters approach.

The modified survey consisted of 44 items with the stem question, “How well did your undergraduate education at Launceston Clinical School prepare you for …”. Participants were asked to respond on a 5-point Likert scale (1, unprepared; 2, not very well prepared; 3, prepared; 4, well prepared; 5, extremely well prepared). One item in the original 39-item survey (“… functioning safely in an acute ‘take’ team”) was not applicable in the Australian context and therefore omitted. The item “… overall patient-centred practice and humane care” was not regarded as sufficiently specific for exploring patient-centred care capabilities and was replaced with seven items more explicitly related to aspects of patient-centred care preparedness (Box 1). Our 10-year experience of implementing and assessing patient-centred learning, including our development of a validated assessment instrument,13 indicated that the seven items were important components of patient-centred practice capabilities. They also reflect elements of expected practice capabilities outlined in the Australian Curriculum Framework for Junior Doctors.14

Additional data (eg, sex, number of years since graduation) were also collected. Qualitative information gathered for deeper investigation of factors affecting transition to practice is not discussed in this article.

Analysis

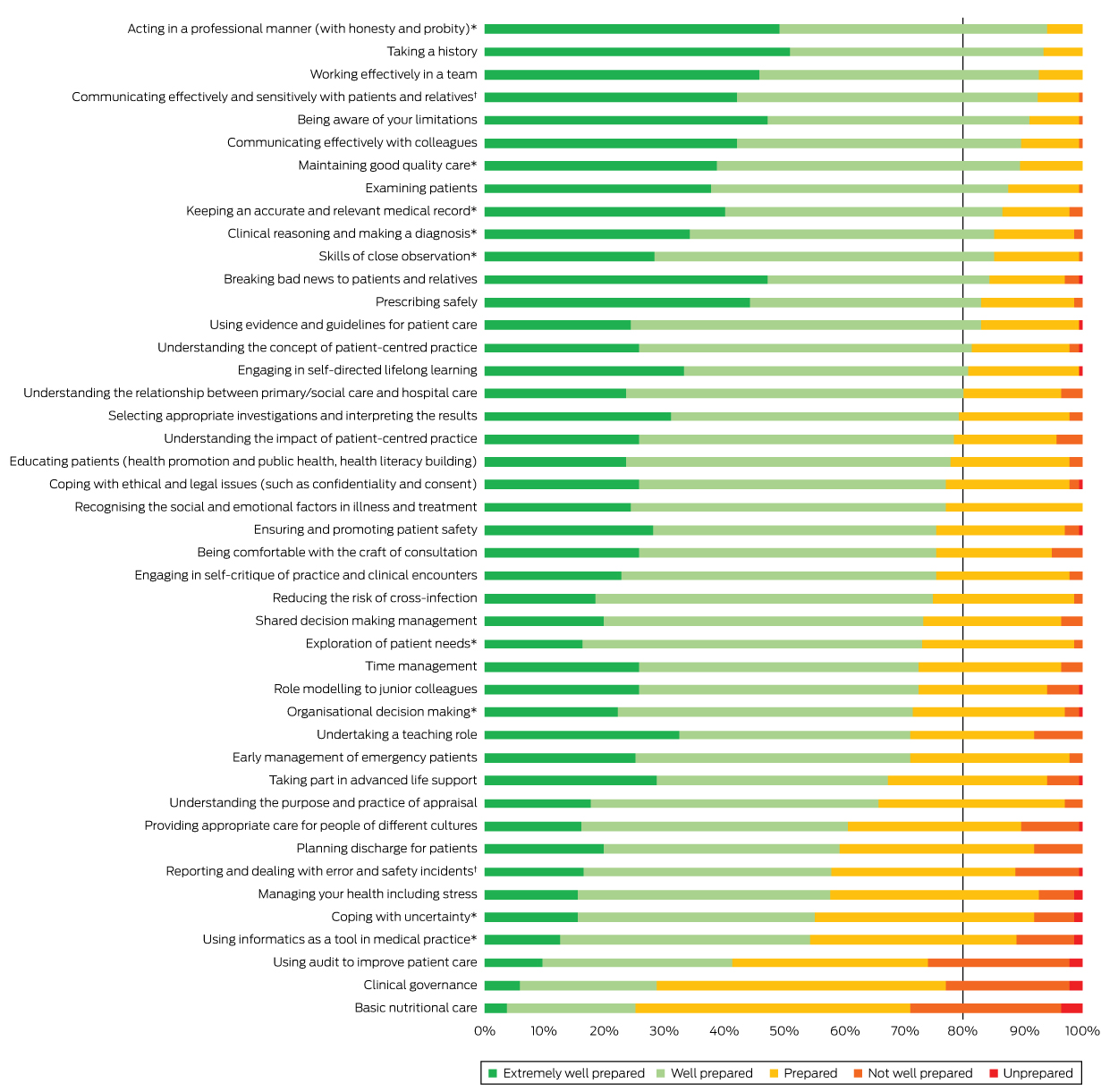

Responses were analysed as counts and percentages; data for all items are presented in a stacked bar chart.

In order to determine the impact of time since graduation on responses, the 44 questions were grouped into six thematic clusters identified independently by each of the four investigators, with the final themes determined by discussion (Box 1). The preparedness scores were ordinal, making an ordered logistic regression analysis appropriate. Including all six themes in a repeated measures analysis allowed each graduate to act as their own control. The relative preparedness scores for each thematic cluster were compared in repeated measures, random effects, ordered logistic regression. The “core skills” theme for those who graduated 1–4 years ago was used as the comparator for generating odds ratios for the other five themes for participants who graduated 1–4 years ago, and for all six themes for those who graduated 5–10 years ago. Data for women and men were analysed separately. In addition, a time interaction analysis compared the preparedness of 1–4 year graduates and 5–10 year graduates in each theme, separately for each sex. The mean preparedness scores (with standard deviations [SDs]) for each theme–time period–sex combination are reported for illustrative purposes only. The responses of participants of each sex in each theme were also compared to assess sex differences in perceptions of preparedness. Analyses were performed in Stata/MP2 14.1 (StataCorp).

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of Tasmania (reference, H0015128).

Results

Survey invitations were sent to the 273 of 359 graduates (76%) for whom current email addresses could be obtained; 147 responses were received (54% of invitees, 41% of the total cohort). Twelve graduates supplied demographic data only, so that 135 graduates were included in the final sample (38% of the total cohort). Of these, 51% were men and 49% women; 71% had graduated in the past 5 years, 29% 6–10 years ago.

For 17 of the 44 surveyed items, at least 80% of graduates reported being extremely well or well prepared. For six items, at least 10% of respondents reported not being well prepared or unprepared for practice: providing nutritional care (29%), using audit to improve patient care (26%), clinical governance (23%), using informatics (11%), responding to error and patient safety (11%), and cultural competency (10%) (Box 2).

More than 80% of graduates felt extremely well or well prepared for only one of the seven patient-centred care items: understanding the concept of patient-centred practice (82%). The figures for the other six items were lower: understanding the impact of patient-centred care (78%), being comfortable with the craft of consultation (76%), shared decision-making (73%), role modelling to junior colleagues (73%), self-critique (76%), and exploration of patient needs (73%).

The 44 survey items were grouped into six broad skills clusters (Box 1). Compared with the core skills theme for 1–4 year graduates, women who had graduated 1–4 years ago perceived themselves as less prepared in all other clusters, except clinical care. Among those who had graduated 5–10 years ago, preparedness for patient-centred care was not significantly different from that for core skills among those who graduated 1–4 years ago. Men who had graduated in the previous 4 years perceived themselves as less prepared than for core skills in all clusters, except for clinical care and patient-centred capabilities. After adjusting for time interaction, the perception of preparedness among men who had graduated 5–10 years ago was statistically significantly higher for core skills and lower for the system-related capabilities group. There were no statistically significant time-related differences for women (Box 3).

For recent graduates (1–4 years ago), there were no significant sex differences in the perception of preparedness in particular thematic groups. Among respondents who had graduated more than 4 years ago, the perception of preparedness was generally higher for men, but this was statistically significant only for the patient-centred care cluster (P = 0.04; online Appendix).

Discussion

A large majority of respondents reported feeling prepared for each of the 44 capabilities covered by the survey. In 17 areas of practice, at least 80% of respondents felt well or extremely well prepared; it is encouraging that these items covered a range of professional, clinical, patient engagement and reflective capabilities, indicating that graduates had a wide-ranging sense of preparedness for their role as doctors. We found some differences in perceived preparedness among male respondents according to whether they had graduated 1–4 years ago or more than 4 years ago. It is not possible to determine whether these changes resulted from changed perception of their capabilities arising from greater professional experience, pre-registration curriculum changes, or recall bias. We postulate that the difference related to changes in their understanding of their role, as there was a significantly different perception of readiness in only two domains (and for men but not for women), and there had been no significant curriculum changes.

This study was conducted at a time of increasing national9 and international1,3,15–17 focus on the preparedness of medical graduates for practice. The General Medical Council (UK) has systematically examined the question over the past decade, and recently reported that one in ten graduates felt poorly prepared for entering medical practice.1,18 Investigations by Australian medical schools have been less systematic.6,19,20 As a consequence of the Medical Intern Training Review, national surveying of Australian interns is now being considered.9,21

Measuring insights about and reflections on practice after commencing work is a worthwhile contribution to understanding the standard of undergraduate medical education and perceived gaps in their readiness to practise as a doctor.3,17,22,23 Viewing preparedness as a continuous non-linear process1 means that it should be assessed as part of an integrated, continuous assessment model encompassing both training and practice.24 Because the performance of graduates continuously improves as they become more experienced, the question of when to retrospectively measure perceptions of preparedness needs to be considered carefully. It should ideally be undertaken at a consistent point in time after commencing practice, when results from different years can be validly compared and are not subject to biases or changes in perceptions attributable to increased experience. Further research will be needed to determine the optimal methodology for such assessment.

If the objective is to prepare a “work ready plus”6 doctor, focusing on our findings relevant to the value-added or non-technical aspects of medicine3 is useful. Preparedness for “engaging in self-directed lifelong learning” and “organisational decision-making” was rated highly, skills need for building professional development, potential leadership, and adaptive capabilities.1 The levels of perceived preparedness for “understanding the concept and impact of patient-centred practice”, “educating patients”, and “shared decision making” indicate the readiness for effective partnering with patients and families for improved health outcomes. The practice areas of “coping with uncertainty” and “reporting and dealing with error and safety incidents” are capabilities that rated less well, indicating opportunities to improve building skills for competently managing unexpected and complex scenarios that arise in health care. “Coping with uncertainty” is a central outcome for Peninsula School undergraduates; they reported a particularly high level of preparedness for this capability, a finding attributed to working with patients and colleagues in activity learning contexts.3 This suggests that when students are directly exposed to key areas of and approaches to practice, their perception of being prepared is enhanced.

That “basic nutritional care” was identified as an area needing improvement is consistent with other findings3 about the capabilities and confidence required to communicate with patients about weight and obesity problems.25 This lack of confidence is important, given increasing population levels of obesity.26

While the overall perceived level of preparedness was high for these graduates, for 61% of the surveyed items fewer than 80% of respondents rated themselves as well or extremely well prepared. There are clear implications for further improving undergraduate medical education, ensuring that graduates feel well or extremely well prepared, rather than merely prepared, by the time they commence practice.

Medical schools should provide patient-centred learning that improve graduates’ capabilities and therefore readiness for the workforce, with safe, high quality care for patients as the goal.27 The LCS curriculum follows a traditional block rotation clinical learning model with a patient partnership program spread across the year and delivered alongside case-based learning.13 As yet there are no data for a direct comparison with non-explicit teaching of patient-centred care that would allow us to determine whether such a program makes a difference to preparedness for patient-centred care. Deliberate patient-centred experiential learning recognises that graduates arrive in a hospital system where “practice in partnership”27 with patients is now expected; aligning the learning continuum expectations with those of the workplace should be driven by this recognition.

Limitations to our study include the fact that respondents’ reflections on their experiences and the expectations they faced in earlier years may have caused recall bias. It is also possible that doctors further out from graduation have different perceptions of preparedness because of their greater experience working in health care. This study is also limited by its being a single site study in a regional university with small graduate numbers, meaning that its results may not be generalisable to other medical schools. Respondents’ interpretation of what constitutes preparedness for each item may also have varied, given that there were no objective criteria for graduates to benchmark their own preparedness.1,15 The judgements of graduates cannot be assumed to be equivalent, although it is likely that each graduate applied similar judgements to each of the 44 items.

Conclusion

Overall, graduates from the LCS felt well prepared for the transition to clinical practice as a junior doctor. Repeated retrospective surveying of our graduates would offer further insights that could inform redesigning areas of the curriculum. If the survey were administered more broadly and a national, longitudinal perspective of perceived preparedness obtained, the results would enhance the integration of the teaching–learning–assessment continuum with service expectations.7,24 A key consideration for such a survey would be the optimal time point after graduation for its administration.

Box 1 –

“How well did your undergraduate education at Launceston Clinical School prepare you for …”: the 44 capabilities included in the survey, grouped into six broad skills clusters

|

|

Core skills

|

|

Taking a history

|

|

Examining patients

|

|

Skills of close observation

|

|

Selecting appropriate investigations and interpreting the results

|

|

Clinical reasoning and making a diagnosis

|

|

Prescribing safely

|

|

Advanced consultation skills

|

|

Educating patients (health promotion, public health, health literacy building)

|

|

Communicating effectively and sensitively with patients and relatives

|

|

Breaking bad news to patients and relatives

|

|

Being comfortable with the craft of consultation*

|

|

Personal and professional capabilities

|

|

Managing your health including stress

|

|

Coping with uncertainty

|

|

Understanding the purpose and practice of appraisal

|

|

Engaging in self-critique of practice and clinical encounters*

|

|

Role modelling to junior colleagues*

|

|

Coping with ethical and legal issues (eg, confidentiality/consent)

|

|

Undertaking a teaching role

|

|

Engaging in self-directed lifelong learning

|

|

Being aware of your limitations

|

|

Acting in a professional manner (with honesty and probity)

|

|

Communicating effectively with colleagues

|

|

Working effectively in a team

|

|

Patient-centred capabilities

|

|

Providing appropriate care for people of different cultures

|

|

Recognising the social and emotional factors in illness and treatment

|

|

Understanding the impact of patient-centred practice*

|

|

Understanding the concept of patient-centred practice*

|

|

Exploration of patient needs*

|

|

Shared decision-making management*

|

|

Understanding the relationship between primary/social and hospital care

|

|

Clinical care

|

|

Using evidence and guidelines for patient care

|

|

Early management of emergency patients

|

|

Taking part in advanced life support

|

|

Maintaining good quality care

|

|

Planning discharge for patients

|

|

Basic nutritional care

|

|

System-related capabilities

|

|

Clinical governance

|

|

Using audit to improve patient care

|

|

Using informatics as a tool in medical practice

|

|

Reporting and dealing with error and safety incidents

|

|

Reducing the risk of cross infection

|

|

Organisational decision making

|

|

Ensuring and promoting patient safety

|

|

Keeping an accurate and relevant medical record

|

|

Time management

|

|

|

* Items added to the original Peninsula Medical School survey.

|

Box 2 –

“How well did your undergraduate education at Launceston Clinical School prepare you for …”: responses for the 44 capability items in the survey, ranked according to the proportion who responded that they were “extremely well prepared” or “well prepared”

Box 3 –

Comparison of responses in the different thematic groups, by sex and time since graduation

|

|

Women

|

Men

|

|

Total*

|

Mean response (SD)†

|

Odds ratio‡ (95% CI)

|

P‡

|

P§

|

Total*

|

Mean response (SD)†

|

Odds ratio‡ (95% CI)

|

P‡

|

P§

|

|

|

Graduated 1–4 years ago

|

|

Core skills

|

234

|

4.2 (0.7)

|

Reference

|

|

|

161

|

4.1 (0.7)

|

1.00

|

|

|

|

Advanced consultation

|

272

|

4.0 (0.8)

|

0.56 (0.38–0.84)

|

0.005

|

|

189

|

3.9 (0.9)

|

0.43 (0.27–0.69)

|

< 0.001

|

|

|

Personal/professional

|

350

|

3.7 (0.9)

|

0.27 (0.18–0.39)

|

< 0.001

|

|

242

|

3.7 (0.9)

|

0.30 (0.17–0.50)

|

< 0.001

|

|

|

Patient-centred

|

468

|

4.0 (0.8)

|

0.59 (0.43–0.80)

|

0.001

|

|

324

|

4.0 (0.9)

|

0.66 (0.40–1.08)

|

0.10

|

|

|

Clinical care

|

156

|

4.1 (0.8)

|

0.80 (0.50–1.27)

|

0.34

|

|

108

|

4.2 (0.9)

|

1.23 (0.75–2.01)

|

0.42

|

|

|

System-related

|

234

|

3.7 (0.9)

|

0.25 (0.16–0.37)

|

< 0.001

|

|

161

|

3.9 (0.9)

|

0.49 (0.33–0.72)

|

< 0.001

|

|

|

Graduated 5–10 years ago

|

|

Core skills

|

215

|

4.2 (0.7)

|

1.01 (0.41–2.49)

|

0.98

|

0.98

|

161

|

4.4 (0.7)

|

2.67 (1.08–6.60)

|

0.033

|

0.033

|

|

Advanced consultation

|

252

|

3.8 (0.7)

|

0.32 (0.12–0.84)

|

0.021

|

0.15

|

189

|

3.9 (0.7)

|

0.84 (0.39–1.80)

|

0.65

|

0.45

|

|

Personal/professional

|

323

|

3.7 (0.9)

|

0.25 (0.11–0.59)

|

0.002

|

0.80

|

242

|

3.6 (1.0)

|

0.40 (0.19–0.85)

|

0.018

|

0.07

|

|

Patient-centred

|

431

|

3.9 (0.8)

|

0.48 (0.20–1.18)

|

0.11

|

0.51

|

324

|

4.1 (0.8)

|

1.66 (0.77–3.59)

|

0.20

|

0.88

|

|

Clinical care

|

143

|

4.0 (0.7)

|

0.50 (0.19–1.34)

|

0.17

|

0.26

|

108

|

4.1 (0.7)

|

1.82 (0.76–4.35)

|

0.18

|

0.19

|

|

System-related

|

216

|

3.7 (0.9)

|

0.24 (0.11–0.55)

|

0.001

|

0.93

|

161

|

3.8 (0.9)

|

0.67 (0.32–1.43)

|

0.30

|

0.038

|

|

|

* Total number of individual responses to questions in the respective category. † Calculated for illustrative purposes only. As the Likert scale responses are inherently rank-ordered (1 to 5; not interval), a rank-ordered analysis was conducted for formal comparisons. ‡ Compared with the responses to the core skills/graduated 1–4 years ago category. § Adjusted for time of graduation (by category).

|

more_vert

more_vert